Massimiliano Pani made headlines before he even opened his eyes. Born in 1963, he inherited not just the genes but the gravitational pull of a woman who reshaped Italian music: Mina. His mother’s voice could shake chandeliers, melt hearts, and defy categorization—pop? Jazz? Bossa nova? Tango? She did it all, and Italians hung onto every note. But in the 1960s, they also raised their eyebrows. When news broke that Mina was expecting a child with actor Corrado Pani—who, inconveniently, was still married to someone else (divorce wouldn’t become legal until 1970)—she was branded a “public sinner” and banished from Italian State Television. Soon enough, however, the clamor for her return drowned out the hand-wringing and she returned to the screen, proving once again that in Italy, rules are meant to be bent and “sins” taken seriously only when it’s most convenient–and that doesn’t include fan-favorite singers.

Mina, Corrado Pani, and baby Massimiliano

Growing up in the long shadow of La Tigre di Cremona might have made some buckle, but Massimiliano charted his own course—as an arranger, composer, and producer ( often for his own mother), orchestrating music from behind the scenes rather than basking in the spotlight. “I was lucky to have two parents so talented that I could never compete with them,” he tells me.

It follows that his musical journey began early, shaped by a childhood spent in and around recording studios, absorbing the nuances of arrangement and composition from some of the industry’s best. By the age of sixteen, Massimiliano had already written and published his first two songs on Mina’s album Attila. He went on to compose and arrange for some of Italy’s most celebrated musicians, including Adriano Celentano, Renato Zero, and Fabrizio De André, and to play a crucial role in producing Mina’s later discography.

On behalf of Italy Segreta, I sat down with Massimiliano to talk about what it means to be the son of Italy’s most formidable voice, the fate of figli d’arte—children of artists who walk the same path—and the kind of quiet genius that keeps the music playing long after the stage lights go dark.

Massimiliano's creative work starting young

Francesco Dama: You once stated, “The figli d’arte I’ve met do nothing but complain—they talk about melancholy, neglected childhoods, and suffer from the complex of having overly famous parents.” I’ve always thought that being born as the child of an artist requires exceptional self-awareness, which only a few achieve. You give me the impression you’ve achieved that very soon. How did you do it?

Massimiliano Pani: Being a figlio d’arte gives you problems only if you decide to pursue an artistic career. It doesn’t interfere if you choose to be a lawyer or a dentist. I was lucky to have two parents so talented that I could never compete with them. That solved the issue for me. I knew I’d never reach their level, so I was always very calm about it. Also, I do a different kind of work—I’m not a singer or an actor. I make records for others as an arranger, composer, and producer, so I operate in a bit of a niche.

FD: I imagine you grew up surrounded by music. Do you remember the moment you “discovered” music?

MP: A pivotal moment came when I was a child. My father was rehearsing Peer Gynt with Edvard Grieg’s music—stunning compositions. I remember sitting in the audience watching, and it wasn’t the actors’ talent that struck me; it was the music. From that moment, I became hungry to learn more about music.

FD: How did being Mina’s son influence you?

MP: I was fortunate to have access to the advice of someone as musically cultured as my mother, who introduced me to many things outside my generation that shaped my taste and awareness. Mina isn’t just one singer—she embodies many styles: Bossa Nova, tango, Latin rhythms, rock, pop, funk, jazz standards, Neapolitan music. Each of these genres has its grammar and literature to understand.

That was incredibly useful when I started working as an arranger because you can’t specialize in just one genre. You need to understand the standards and the pieces. That’s the beauty of this job—constantly listening, learning, and confronting different musical genres to find what’s beautiful in each one.

FD: August 23, 1978–Mina’s last concert at Bussoladomani. You were fifteen. Do you remember it? What was her relationship with the audience like?

MP: Of course, I remember it. That was the only concert I saw because she never performed live again after that. I had the honor and luck to hear her sing live thousands of times in the studio, but that’s a different experience—it’s a different type of work.

That concert was fascinating because she had a stage presence and charisma that could not be explained. When she finished a song, people didn’t just clap their hands, they stomped their feet. They would make as much noise as possible. And then she’d go like this [Massimiliano makes a stop gesture with his hand], and silence would fall instantly. Her aura strikes you beyond the technical aspects you might analyze. It was awe-inspiring. You could see this even on television. When she was on shows like Studio Uno or Teatro 10, there would always be a guest—back then, the guests were legends like Marcello Mastroianni, Vittorio De Sica, Totò, Alberto Sordi… She stood alongside these giants with elegance and presence—not as a secondary figure but as an equally authoritative personality. And then you realize how young she was—just twenty-four years old. Her physicality and charisma were especially evident live on stage. That concert left a strong impression on me.

Mina live at La Bussola in 1972

FD: You wrote your first song for your mother the following year. How did it go?

MP: Yes, I have been writing since I was very young. It took me a while to create a good song. I published the first two on the album Attila when I was sixteen. I wrote them with a friend I used to meet up with to compose songs. We were just kids. I played one of our compositions to her, she liked it and let me do it. Beppe Cantarelli, who arranged the entire album, did the arrangement. One of the first singles from that album, “Sensazioni”, was mine. It was a great satisfaction.

FD: Mina was twenty-four years old and already dominating the scene, but you, at sixteen, wrote one of Mina’s singles, which is no small feat.

MP: It was a great motivation, of course. Another critical moment for me was when I met Piero Cassano, who is the author of all Matia Bazar’s songs: “Ti sento”, “Solo tu”, “Che male fa”, “Vacanze romane”… and he also produced all the most famous songs by Eros Ramazzotti. Cassano gave me a cassette tape with some unfinished music, probably just to be kind, and he asked me to finish the tracks. I don’t think he believed I could work on them. I finished them, and from there we started working together. We’re still working together today. We collaborated on projects for albums he produced, like Anna Oxa’s, and many projects in France and Spain. That beginning led me to connect with other writers and collaborate on many crucial jobs for my growth. You know, you can’t really learn to write songs, but you can learn to understand what works and what doesn’t—in fact, you must. Having a more experienced songwriter to guide you helps a lot.

FD: He was your mentor.

MP: Yes, a mentor, along with Celso Valli. I initially followed him in the studio because he arranged for my mother—I was eighteen or nineteen years old then—and later, I followed him on other productions he worked on. With him, I learned things you won’t find in books. Being an arranger is a job that involves musical grammar and harmony, but it also involves aspects that are difficult to teach.

FD: I imagine there’s a lot of individual sensitivity involved. It’s a highly creative job…

MP: It is undoubtedly tied to your taste and sensitivity. But there are also methods you need to learn. When you enter a recording studio, talented musicians are there waiting for you to tell them what to play. So all the preparation is essential. The better organized the work is, the less time you waste, and the less money you spend. These are things I learned very early from Celso.

FD: When did you realize you wanted to do this for a living?

MP: Very early. At fourteen or fifteen. Back then, we had a recording studio in Italy, on Corso Italia in Milan, in a deconsecrated basilica called La Basilica. When I could, usually on Saturdays, I would go there and sit quietly in a corner to observe. That’s when I realized I wasn’t interested in live performances but rather in making records—a behind-the-scenes job, not a front-and-center one. To make an analogy with cinema: not working as an actor, but working as a director.

Mina and Massimiliano in the studio; ©PDU

FD: PDU (Platten Durcharbeitung Unternehmungen, “Produzione Dischi Ultrafonici” in Italian) was founded in 1967 when Mina realized that, to protect her artistic independence, she needed to create her record label. Can you tell me more about it?

MP: Mina is Mina because she understood so many things before anyone else. She realized that television was changing and decided to do something different. She understood that to protect her artistic independence, she needed her own label and recording studio to have the calm, time, and space to realize her projects. This is because, if you work for a record company, they will always push you to do more of what has worked before. If “Acqua e sale” sold well, they’ll want you to make “Acqua e sale” for the rest of your life. Mina understood that she needed her own label to avoid mediations and alterations to her music. She proved to be correct. She created PDU with her studio and, from there, assembled a catalog—mainly her own work, but also others’—that represents her.

FD: Giacomo Mazzini, Mina’s father—your grandfather—was involved from the start of PDU. You’ve been managing the company since 1987. What’s it like working in a family business?

MP: It works very well if you have a leader who is also an enlightened person, like my mother. She is truly exceptional. When you talk to her, you’re not talking to a relative; you’re talking to your employer, who gives you instructions. There’s no overlap, no debate. It’s a different level of relationship. These dynamics exist in other fields, too. Think of how many doctors or lawyers come from generations of the same profession. A child or grandchild joins a firm and learns things from a family culture, which is passed on and continues.

This often happens in music, too. Many instrumentalists are children or grandchildren of musicians because it’s a career that profoundly influences you. The same happens in sports. Think about Cesare Maldini, who had a son, Paolo Maldini, who is considered the most excellent defender in history, and a grandson who also plays soccer. For me, it was easy because my mother has such intelligence and a clear vision of what she wants to do. Your role is clear: you have to bring her idea to life.

FD: Is that how an album with Mina comes to life?

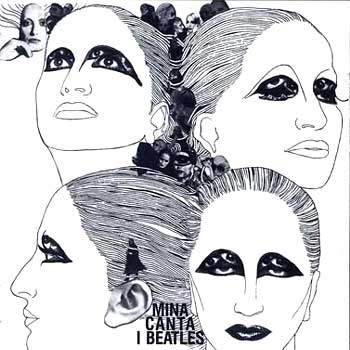

MP: Whether it’s an album of original songs like her latest, Gassa d’amante; one dedicated to a musical genre like Mina canta o Brasil; or to a composer like Mina canta i Beatles or Paradiso (Lucio Battisti Songbook), she has the project in her mind. Then she gives you a lot of room to work on it—that’s another trait of truly great people. Once you understand the direction, she lets you work.

Mina canta i Beatles (1993); ©PDU

FD: For those of us born in the 1980s, Mina’s album covers are the only visual representation we have of her, especially in an era in which a musician’s image is often as vital as their music. Artists like Madonna and Lady Gaga have deliberately used their physical presence as part of their artistry. You often speak about the “destruction” of Mina’s image, but wouldn’t it be more accurate to say she carefully reconstructed “in absentia”?

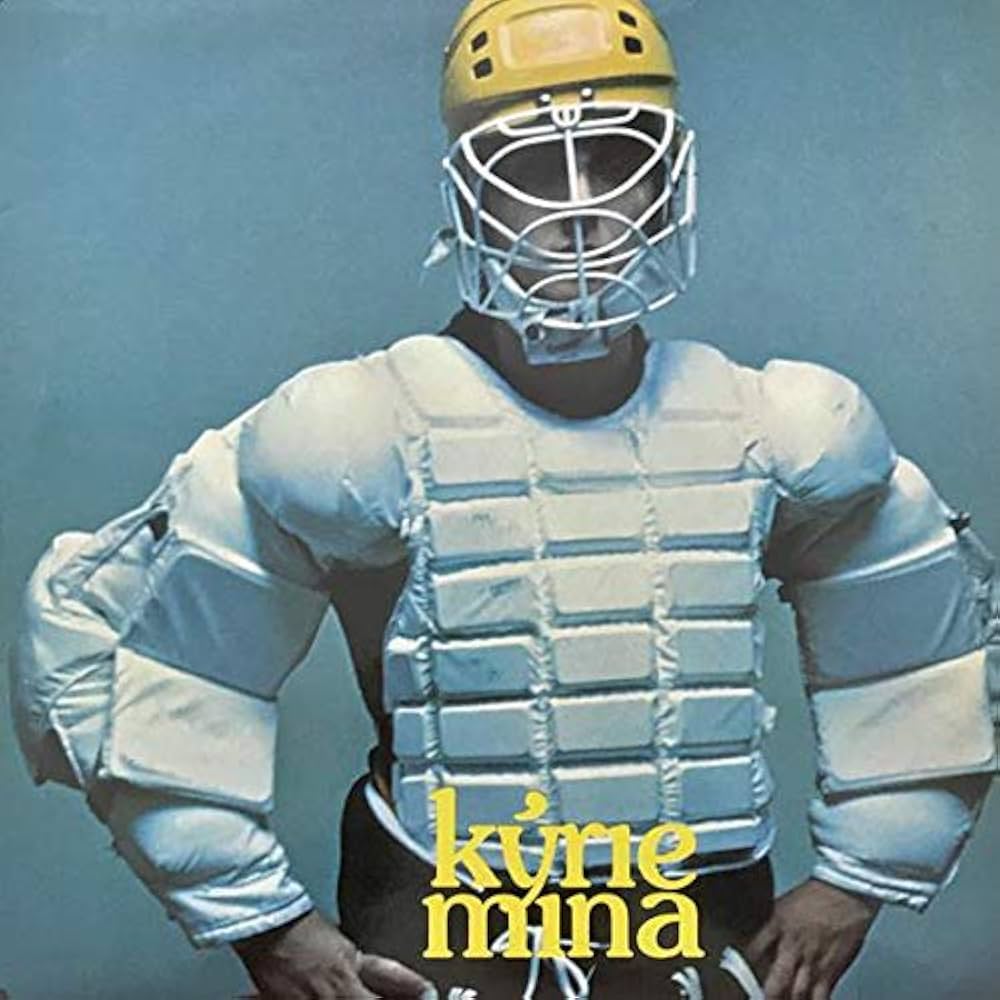

MP: In the early ’70s, Mina represented Italian television. She was at the pinnacle of Saturday night entertainment and was everywhere—constantly on TV, in newspapers, under enormous media pressure. She was stunning, 34 years old. At some point she got tired of seeing the same face. So she said: “Enough: I’ll become a monkey, a duck, an alien, a bodybuilder, I’ll grow a beard…” She began playing with transformations of herself.

To do this, she found a young man, Mauro Balletti, who started as a painter and whom she turned into a photographer and designer. She had the ideas, just like she does for her albums, and he brought them to life. Together, they created things that weren’t even possible back then. There was no Photoshop, no computer. But that was their strength. They managed to do something unprecedented.

For example, to create the cover of Rane Supreme, he photographed a bodybuilder and then Mina’s profile. He had to adjust the proportions between the torso and head, cut out the images, reassemble them, blend them at the neck with spray paint, and re-photograph everything again. Today, you do that in three seconds. Balletti worked on it for weeks.

Interestingly, through this game, she created something more: the covers of her albums became as important as their songs. She started making bolder and more daring covers. Mina had this vision some twenty years before Madonna and thirty years before Lady Gaga. She turned her image into something timeless–because Mina is timeless.

Kyrie 1980 Photo Mauro Balletti ©PDU

FD: You even ended up on one of these covers: Kyrie, from 1980.

MP: Yes, that was by chance. She wanted the image of the kit worn by a hockey goalie. We went to the ice rink in Como to take photos, and the kit they had rented was too small for the player who was supposed to wear it. I was around because it was a Saturday. I was on holiday, so I must have been sixteen or seventeen. It fit me, so they had me wear it.

FD: Since Mina retired from the scenes, there have been countless speculations about her life. How do you respond to the media’s curiosity?

MP: The most exciting thing isn’t her private life but what she’s accomplished in her career: her courage and determination to follow her path. That’s incredible. Think about it: a record [Gassa d’Amante, Mina’s latest album] has just been released by a 85-year-old woman whose last concert was in 1978 and whose last TV appearance was in 1974. The album is number one on the charts. This doesn’t happen anywhere else in the world. No one else would manage to stay relevant with the choices she made. Today, if you’re a singer, you either do everything—TV, movies, radio, social media, concerts—or you’re out of the game.

So the truly incredible thing isn’t her [personal] life but her choices and what they’ve led to. When she decided to stop doing TV and concerts, [her music] was distributed by the record label EMI. EMI terminated her contract. Mina took full responsibility. Today it seems easy, but it was an act of immense courage back then.

And she remained consistent. Mina is one of the few people in this country who said something and followed through.