Together with Cortina and Courmayeur, Madonna di Campiglio completes the triad of Italy’s most famous ski destinations. It’s a territory of excellence, or Altagamma—to borrow the phrasing of the association uniting the country’s top Made in Italy brands like Ferrari and Gucci, of which Campiglio is a member.

It is undeniably a luxury destination, but you won’t find the Olympics here. The peaks framing your window aren’t those Dolomites; you’re not in Alto Adige, after all, but in Trentino. For expert skiers and slalom fans, this is paradise; for others, Campiglio has perhaps been viewed as a dupe destination for its more famous cousins—but not for much longer.

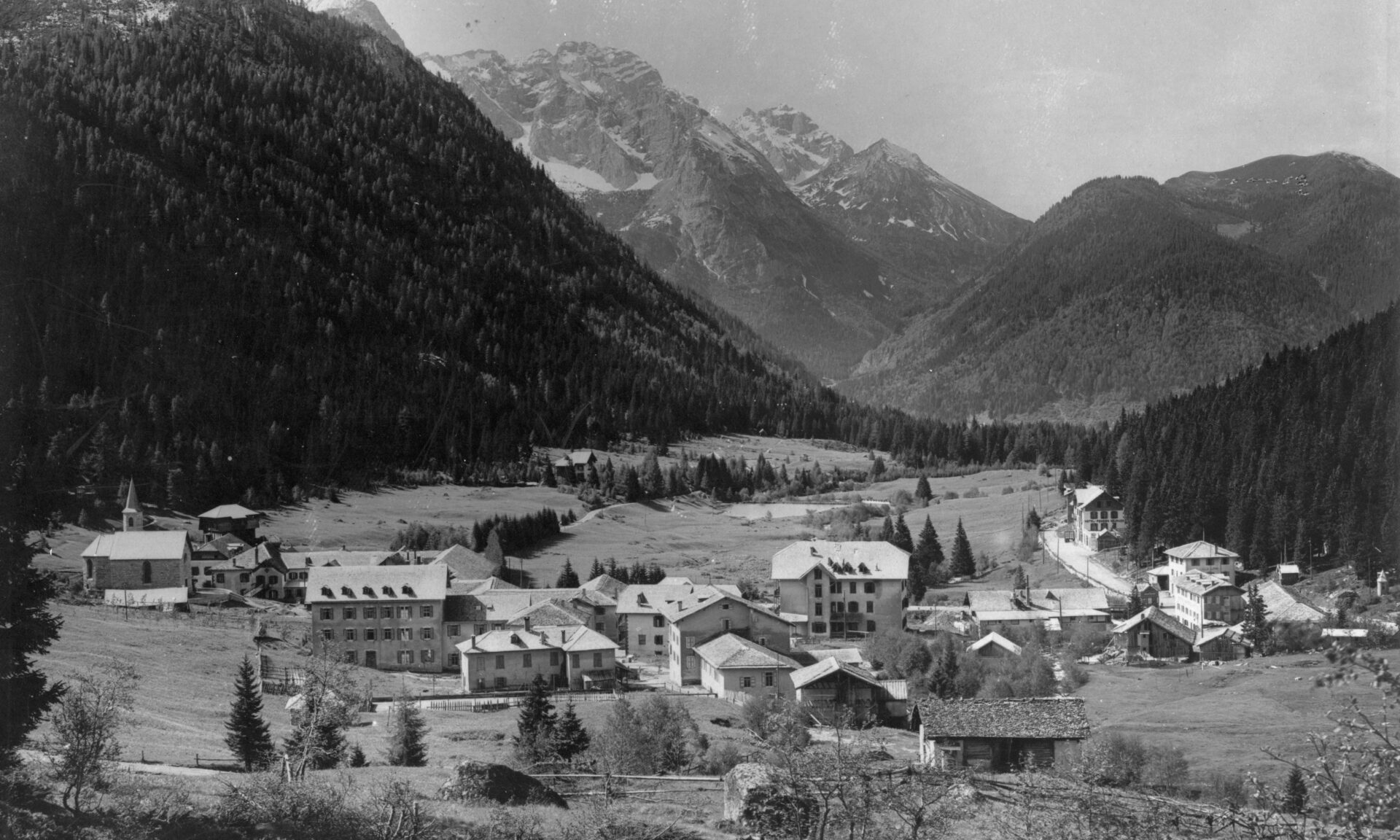

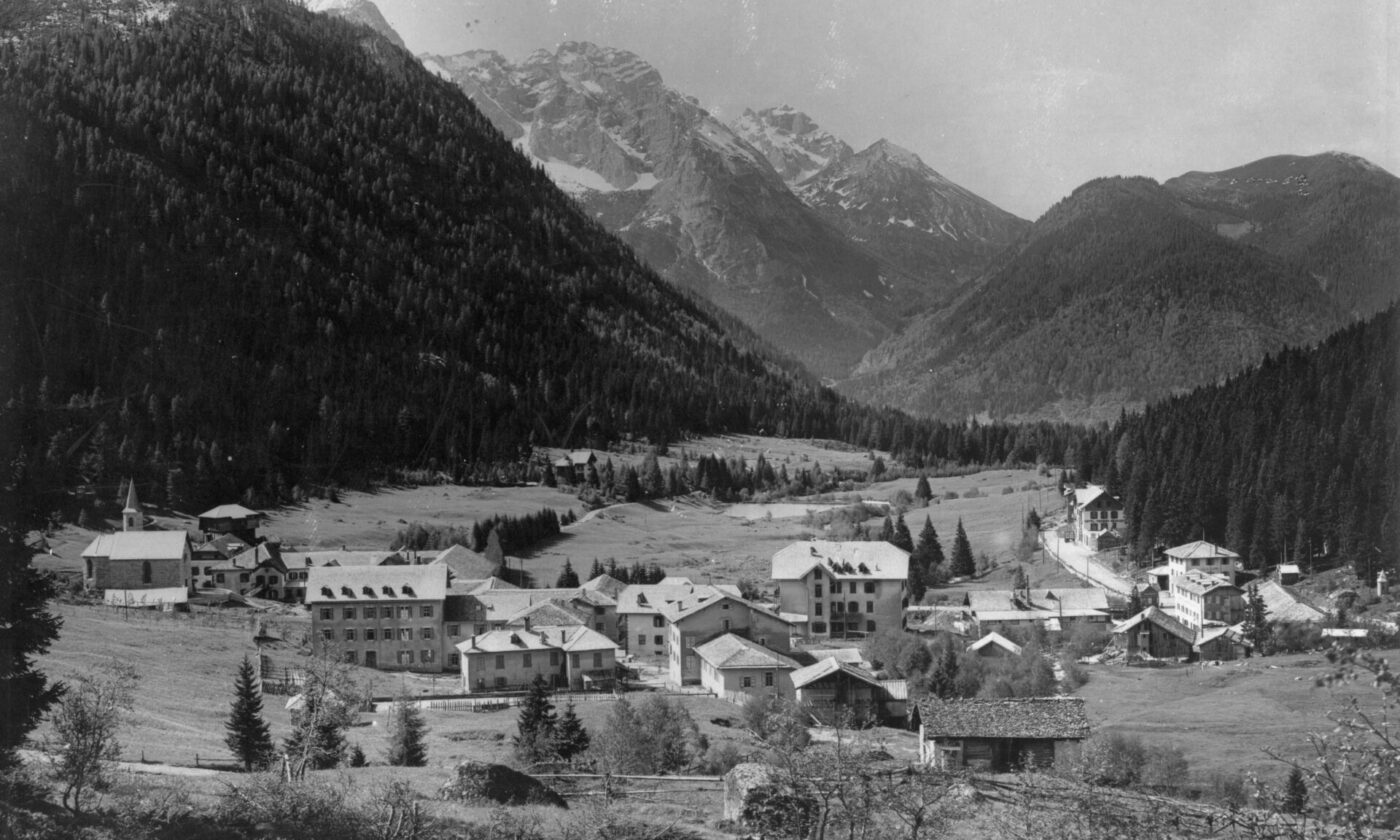

Madonna di Campiglio is in the center of the Val Rendena, flanked by the Brenta Dolomites to the east and the glaciers and granite massifs of the Adamello-Presanella to the west, all within the protection of the Adamello Brenta Natural Park. It lies in a sunny, open basin, yet sits at a formidable altitude of 1,552 meters above sea level.

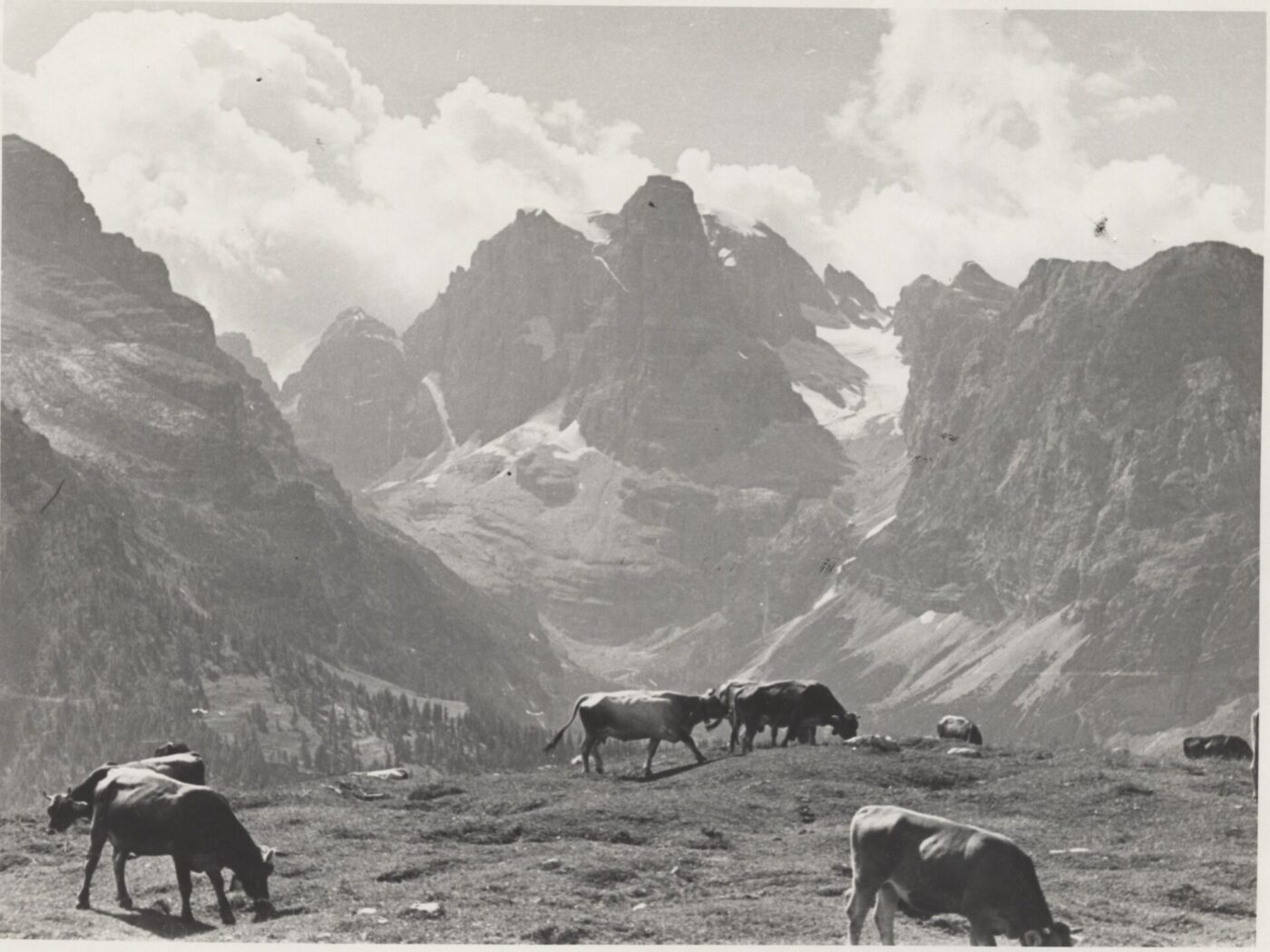

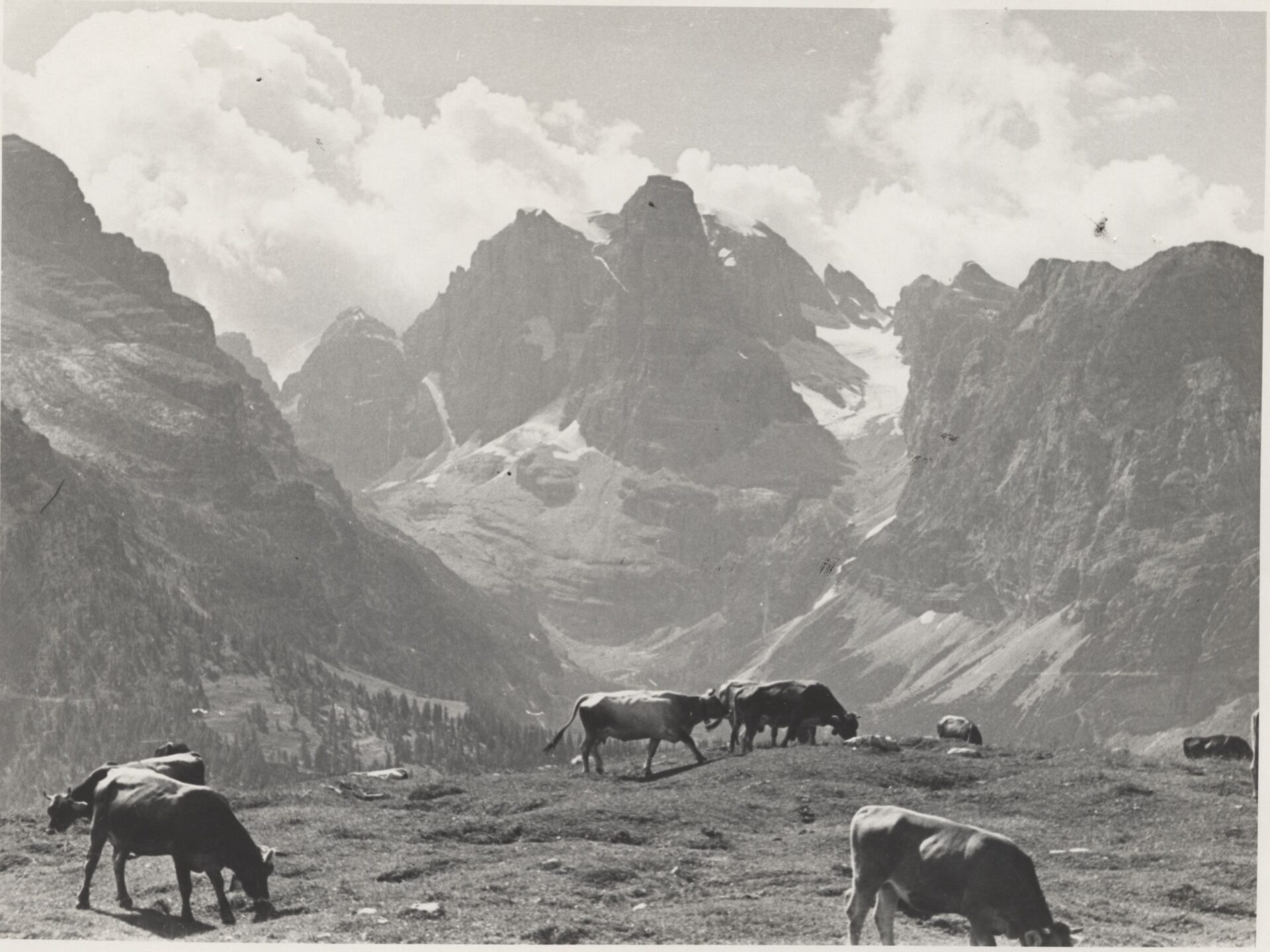

Monte Spinale, 1953; By Touring Club Italiano, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=132723965

Like many mountain localities, it shares a common, poverty-stricken history: a land that relied on cattle and alpine pastures until the invention of mountain tourism revolutionized it. In the 18th century, a thirst for exploration drove the first English and German mountaineers to Italy to conquer peak after peak. Yet, while they began with Monte Bianca in 1786, they didn’t reach the Brenta Group until 1885. This century-long delay explains why the name Campiglio took longer to spread across Europe—and why, even today, it has trailed slightly behind its peers in fame.

The village’s second life began with a gamble by Gianbattista Righi. In 1868, he purchased an abandoned monastery and converted it into the first hotel, the Stabilimento Alpino, constructing the first road to connect Campiglio to the valley below. But it was Franz Josef Oesterreicher who transformed Campiglio into a playground for the nobility and the wealthy Austrian bourgeoisie. Between 1889 and 1894, his guest list counted names like Princess Sissi and Emperor Franz Joseph—arguably the original influencers of mountain tourism. They came to breathe the fresh air, to hunt, to walk, and to spend the evenings dancing—reenacted today during the annual costumed Habsburg Carnival, held in the Hofer Hall of the Hotel Relais Des Alpes, Campiglio’s most iconic.

The piazza in Madonna di Campiglio named after the Empress Sissi; Courtesy of VitVit - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52351585

“Sissi was here” is Campiglio’s mantra (as in Merano), and the Empress’s image is ubiquitous: on postcards, souvenirs, and in the names of trails and venues. Marketing, I think to myself as I stroll through the town center where you do breathe an air of the past, though perhaps not quite the air of the Empress’s time.

Beside the old late-19th-century chapel, a brutalist church has been erected. Sissi’s hotel is unrecognizable compared to period photographs; today, it has five floors and is part of a package-holiday group. The apartment blocks of second homes and central hotels present a catalog of Alpine style interpretations—of varying degrees of success—drafted by the architects (or perhaps surveyors) of recent decades. Regardless, an old-school charm remains: you stop for a coffee and pastry at Bar Suisse, browse for a wool sweater at Stile Alpino, and shop windows entice you with herbal teas, local cheeses, and liqueurs.

Following the Giro di Campiglio, you trace a path through the woods encircling the village, enjoying the vantage point from above. Down below, you’re surrounded by mountains but not the imposing Dolomite panorama you’d expect. You need only ascend slightly, however, to reveal a landscape of surprising variety—not by chance, you’re in the middle of a UNESCO Geopark.

Courtesy of Manuel righi - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=125303650

On one side rise the sharp peaks of the Brenta Dolomites; on the other, the granite massifs of the Adamello-Presanella, speckled with glaciers and alpine lakes. This was also the highest front of WWI; between 1915 and 1918, battles raged here at 3,000 meters. A local museum, the Museum of Campiglio Mountain Guides and People, memorializes that unforgiving mountain we forget today as we glide comfortably up and down in cable cars, waiting for nothing more than a thrilling descent.

While the first ski lift—the Belvedere toboggan lift—dates back to 1936, today the Madonna di Campiglio Ski Area boasts 57 lifts serving 150 km of slopes. These include the legendary Canalone Miramonti, where the 3Tre World Cup race is held, and the Schumacher slope, named after the driver who favored it. With a 70% gradient, it’s practically a vertical wall.

Winter here is, unsurprisingly, the busiest season—so intense, in fact, that a visitor cap has been introduced for the first time. During the frantic window between Christmas and New Year’s 2025/2026, daily access will be limited to 14,000–15,000 skiers. However, while people have always flocked here for the snow, Campiglio’s future seems destined to also lie elsewhere—and not only because of climate change.

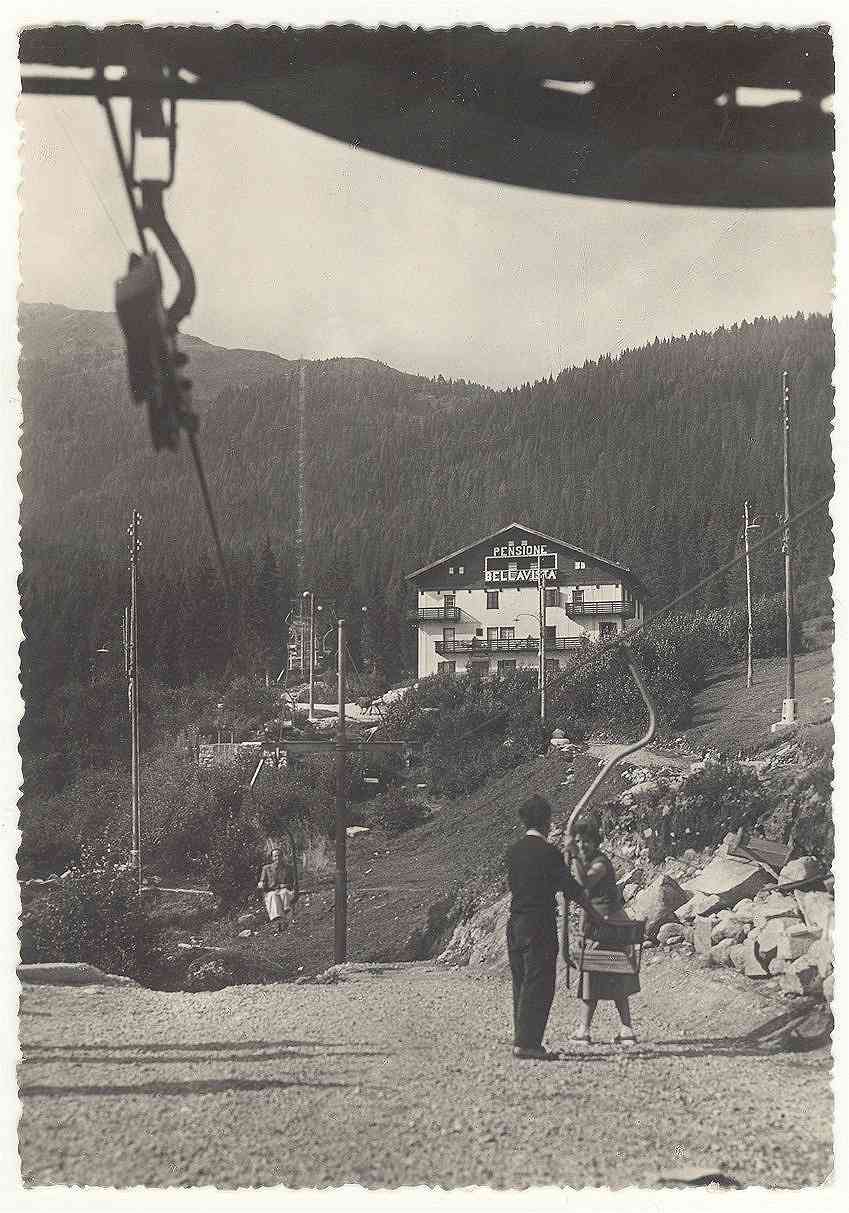

Seggiovia di Pradalago ski lift in front of Pensione Bellavista, m.1553; By Albertomos - Collezione cartoline Albertomos, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8646169

Today, the village center has an artificial lake, built in 2014 by the ski lift entrepreneurs. The streets are dotted with e-bike charging stations, and recent years have seen the unveiling of extensive new summer trekking networks—including major projects like La Via delle Valli, which offers enough trails to keep hiking enthusiasts occupied for years.

When they aren’t leading groups on skis, the Alpine Guides curate a calendar of excursions and tours designed to showcase the territory in every season. Historically, tourism here has been driven by Italians—many of whom purchased second homes during the boom of the 1970s and ’80s—alongside a contingent of English and Polish visitors. Yet, simply extending the season isn’t the only strategy for drawing more people to Campiglio. There are entire new categories of travelers to woo: those who do not yet know this place, and perhaps have never even heard its name.

To us, it’s simply Campiglio. But for a new wave of travelers, it’s Madonna, easier to pronounce, perhaps, and possessing a quintessential Italian ring. Though seeing it written that way, or hearing it repeated in a British accent, provokes a wry smile.

The town recently welcomed the country’s first Casa Cook hotel—yes, Cook, as in Thomas Cook, the man who launched the world’s first travel agency in London in 1841 and effectively invented organized tourism. The group took over the old Hotel Milano, a relic of the economic boom years, gutted it, and transformed it into an alternative hub for international travelers and a younger crowd seeking a contemporary edge. Through their various properties in Greece and Egypt, the brand has cultivated a loyal community that shares a specific way of traveling and seeks a distinct style of international hospitality.

Courtesy of Lefay Madonna di Campiglio

Inside, almost no one speaks Italian. The chef is Dutch, and every detail deliberately distances itself from the alpine stereotype and from the surrounding offer. Long-time aficionados, who’ve been coming here for decades, will like it little—as with much of what is emerging nearby. These places are united by a new style, which means a new lifeblood for a destination showing its first signs of revival.

In 2019, just a few kilometers away in Pinzolo, the luxurious and immense Lefay Resort & SPA Dolomiti opened its doors—famous for a spa spanning three levels and over 4,000 square meters, with a vast pool and an entire floor dedicated to saunas and thermal zones.

Higher up, the Rifugio Doss del Sabion Alpine Style has been renovated from top to bottom, revealing a new panoramic bar and restaurant. The Patascoss—one of Trentino’s oldest chalets—has also reopened, housing four distinct restaurants devoted to sustainability. Then there’s the arrival of Super G, Italy’s most famous après-ski brand. Born in Courmayeur, it has launched a new club here, enticing even non-skiers to dance on the slopes.

This new season also welcomes Meraviglioso, a dining concept originally from Porto Cervo. Meanwhile, down in the valley, La Zangola, a legendary disco of days gone by, has been taken over. Nights will run late here once again, and Madonna di Campiglio is poised to rediscover something it had lost: its nightlife.

There will be those who turn up their noses; these new ventures are all driven by outsiders. But Franz Josef Oesterreicher was once branded the very same way—a “foreign usurper” who “colonized” the valley. Today, he’s unanimously celebrated as the pioneer of Trentino tourism. This time, however, it won’t take a century to reach a verdict.