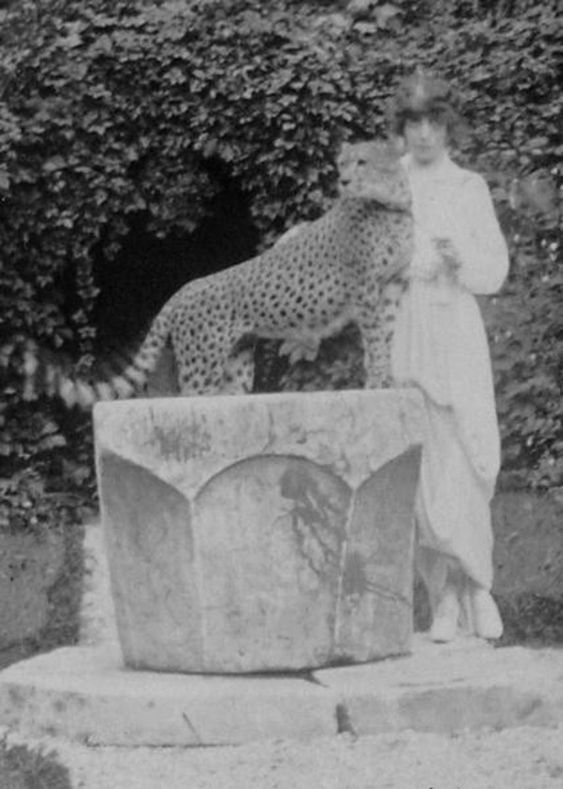

She walked pet cheetahs on diamond leashes, wore live snakes as jewelry, and dined with a wax mannequin in her own likeness. Often called the original female dandy, Marchesa Luisa Casati Stampa curated her existence, flirting with the uncanny and the beautifully absurd with a commitment that makes today’s so-called eccentrics look tame by comparison.

She was photographed by Man Ray, painted by Giovanni Boldini, Kees van Dongen, and Joseph Paget-Fredericks, and inspired the theatrics of John Galliano, the drama of Alexander McQueen, and the sharp silhouettes of Karl Lagerfeld. For over a century, artists and designers have mined her myth. And this August, in Anacapri, her legend takes new shape with a permanent exhibition at Villa San Michele.

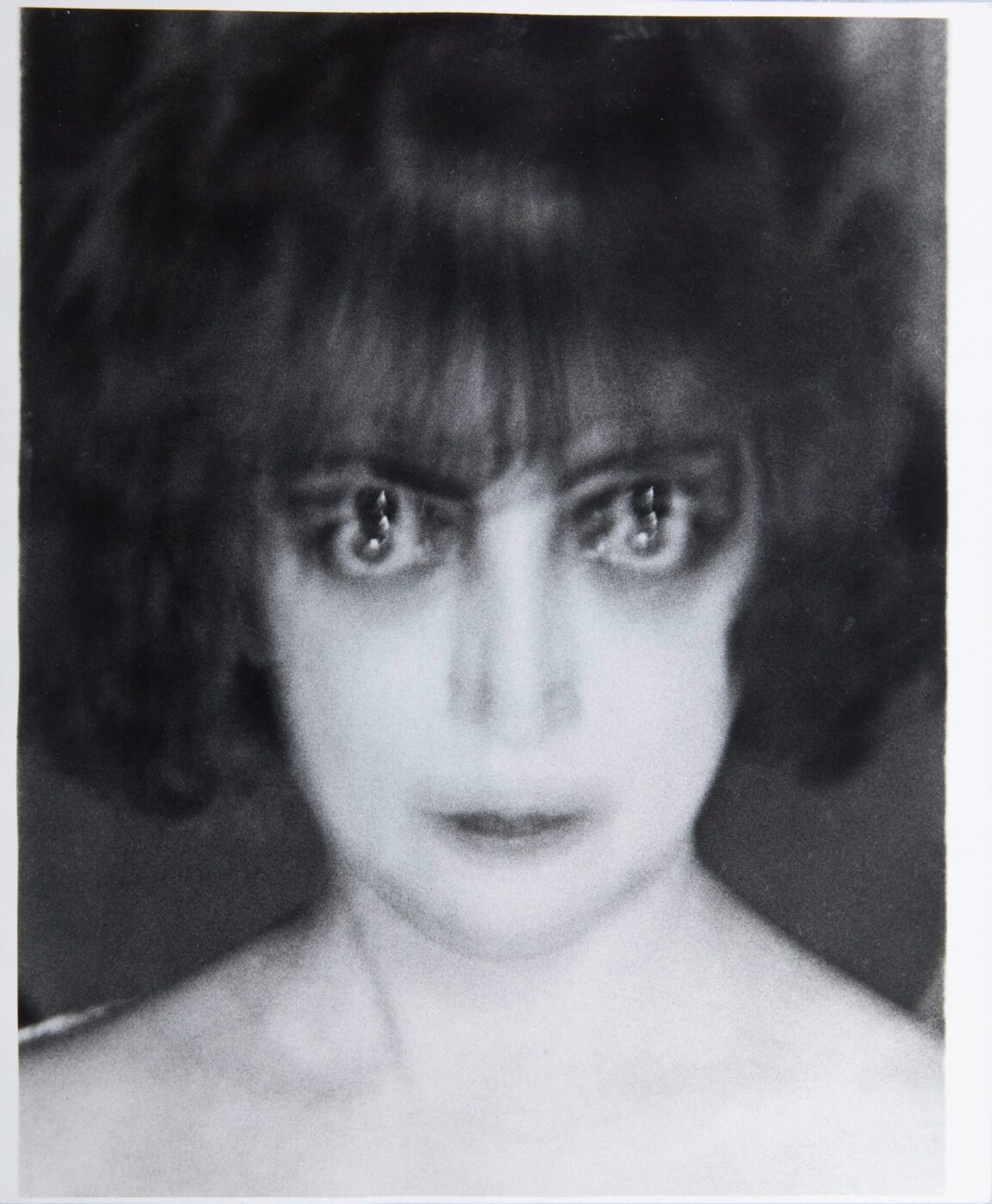

Portrait of Marchesa Luisa Casati. Museum: © Man Ray Trust.

The location couldn’t be more perfect. Casati herself rented the villa in the 1920s from Axel Munthe, the Swedish doctor and writer who built it. Now, curated by Swedish costume designer Nils Harning and set designer Anna Bergman, the space is not your typical retrospective.. Most of Casati’s possessions, from Bugatti-designed furniture to custom Schiaparelli gowns, were famously auctioned off after she racked up a personal debt of $25 million during the 1930s, which means the designers have had to work off of fragments and rumors.

“We had to manufacture a great number of items,” Harning tells me. “The only object of hers we have is a table, a small marble one with a sphinx plinth. According to legend, she placed her crystal ball there.”

Well, yes, she had a crystal ball. But let’s rewind.

Luisa Casati Stampa was born Luisa Adele Rosa Maria Amman on January 23rd, 1881, in Milan to a family of immense wealth and newly granted nobility—her father, a textile magnate, had been made a Count by King Umberto I. Raised in a devout Catholic household near Lake Como, her early life offered little hint of the scandalous path she would later forge. She was often described as a shy introvert with a fiercely independent streak.

It was only later, after inheriting a vast fortune at the age of 15 (and becoming reportedly the wealthiest woman in Italy along with her sister), that Casati began to reinvent herself.

She married the Marquis Camillo Casati Stampa di Soncino in 1900—a union that seemed to cement her place in Italian high society as a Marchesa, a title ranking just above countess. Camillo, heir to a substantial fortune, offered Casati the status and means to live lavishly. But it quickly became clear that her ambitions stretched well beyond the traditional role of her title.

This is where the exhibition begins.

Nils Harning and Anna Bergman; Photo courtesy of Giulia Kappelin Cingolani/Villa San Michele

Harning and Bergman have commissioned nine life-sized 3D-printed figures of Casati to chart her evolution from innocence to decadence. “The first statue, dressed in white, represents her innocence at the time of her marriage,” explains Anna Bergman, moving her hands in the air to suggest the chaos that is to come. “She wears a high-necked dress from the late 1800s or early 1900s. The second is red, portraying her as a wife with a large hat and elegant hair. Then she cuts her hair, and in our timeline, she meets Gabriele d’Annunzio—who tells her she needs to live.”

It was a love story for the ages—passionate, tumultuous, and set against the backdrop of Venice. Casati’s affair with poet and playwright Gabriele d’Annunzio was more than romance; it was a creative collaboration. A man who spent his life dodging his creditors and always in search of a wealthy patroness, d’Annunzio found both inspiration and indulgence in Casati. Fidelity wasn’t exactly their strong suit, but she became his muse, and he urged her toward excess, fueling her transformation into a living work of art—a bond that would endure for life.

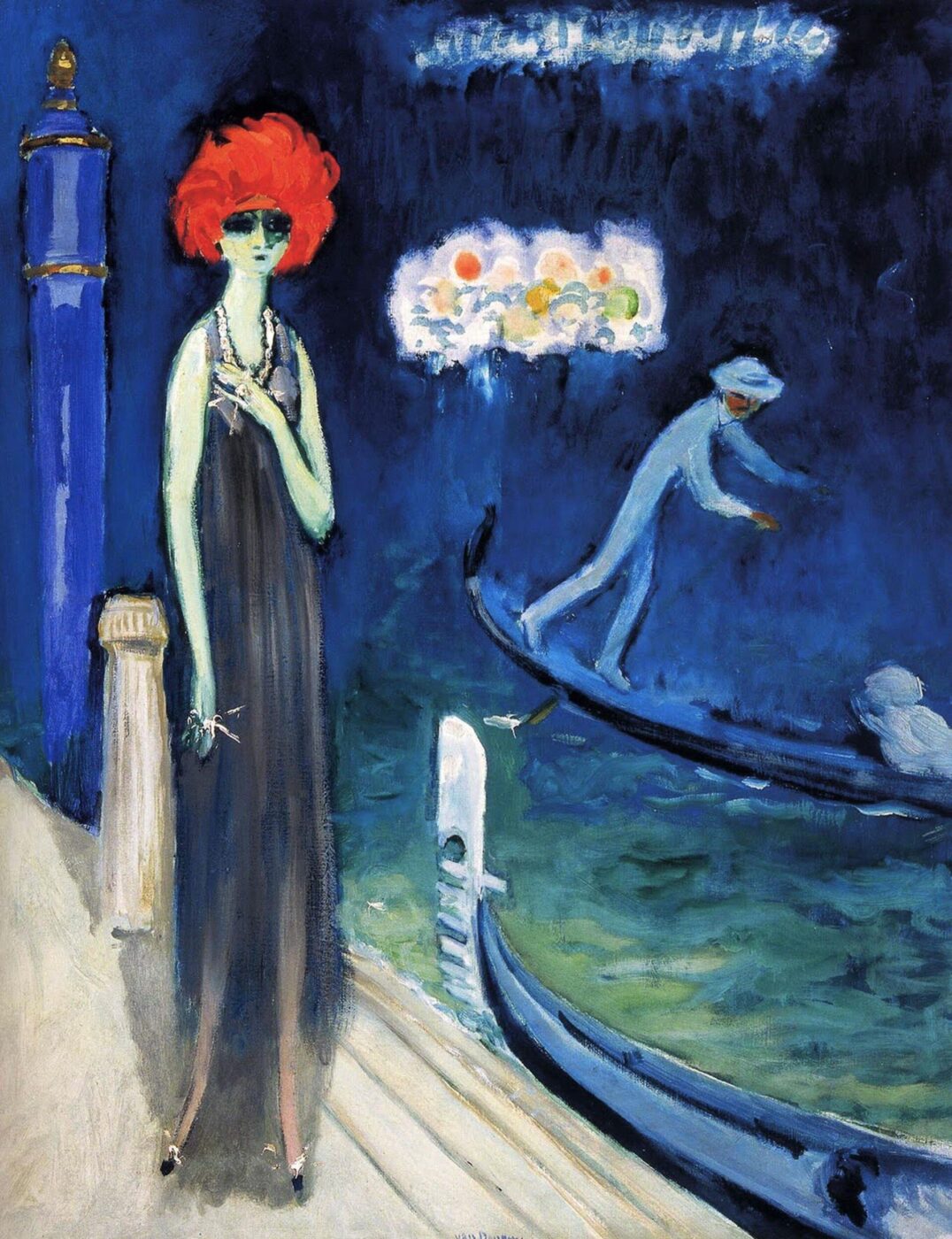

After leaving her husband following the birth of their only child, Casati transformed Palazzo Venier dei Leoni on the Grand Canal (later to be owned by another force of nature, Peggy Guggenheim, and now the Peggy Guggenheim collection) into a stage for her extravagant fantasies. She hosted decadent parties amid a surreal menagerie of exotic animals and a wax figure of herself (with green glass eyes and a wig allegedly made from her own hair, it dined with her, dressed as her double, and even accompanied her to Paris for fittings at Poiret). Guests included Picasso, Man Ray, and dancers from the Ballet Russes, mingling among crystal balls and lions borrowed from the zoo. When jewels didn’t suffice, she’d turn white peacocks into accessories or wear a boa constrictor (while living at the Ritz in Paris, live chickens and rabbits were required daily to feed it). At one masquerade, she arrived wearing a “necklace” of slithering snakes.

Luisa Casati (Italian heiress, muse, and patroness of the arts) - dress possibly by Jean-Charles Worth - 1922

Casati’s perhaps most infamous fashion moment took place at the Beaumont Ball in Paris, 1924, where she wore a lightbulb-studded dress powered by a hidden generator. The gown was so elaborate she reportedly got stuck in a doorway, the dress short-circuited, and an electric jolt was sent through her. True to form, she carried on through the evening. Or maybe it was when, for a night at the opera, she paired a towering headdress of peacock feathers with the blood of a freshly killed chicken.

On other occasions, she paraded through Venice at night wearing little more than a fur coat and layers of pearls, leading leashed cheetahs in diamond collars while servants carried lanterns behind her. Peacocks, white doves, and even dyed pigeons often accompanied these surreal nocturnal processions.

Casati and her cheetah

At six feet tall and eerily thin (some credit a cocaine habit), Casati was no conventional beauty, yet she made herself utterly unforgettable. Her black hair was cut short and dyed into a fiery red that popped against her pale skin, powdered to an unnatural white. Her dark green eyes—her most hypnotic feature—were rimmed in thick black kohl, framed by false lashes and, when the mood struck, even strips of black velvet. She embraced fetishism and openly displayed the bruises and bite marks left by her entanglements with d’Annunzio. To intensify the effect of her gaze, Casati reportedly used belladonna—a toxic substance that dilated her pupils into an unnervingly otherworldly stare.

Harning describes her as “the mother of her look”—a vampiric icon who inspired a cult following both in life and after.

“She was a pioneer,” he says. “All those smoky-eyed movie stars in early Hollywood owe their style to her. That heavy, oriental aesthetic she created has influenced fashion designers for decades.”

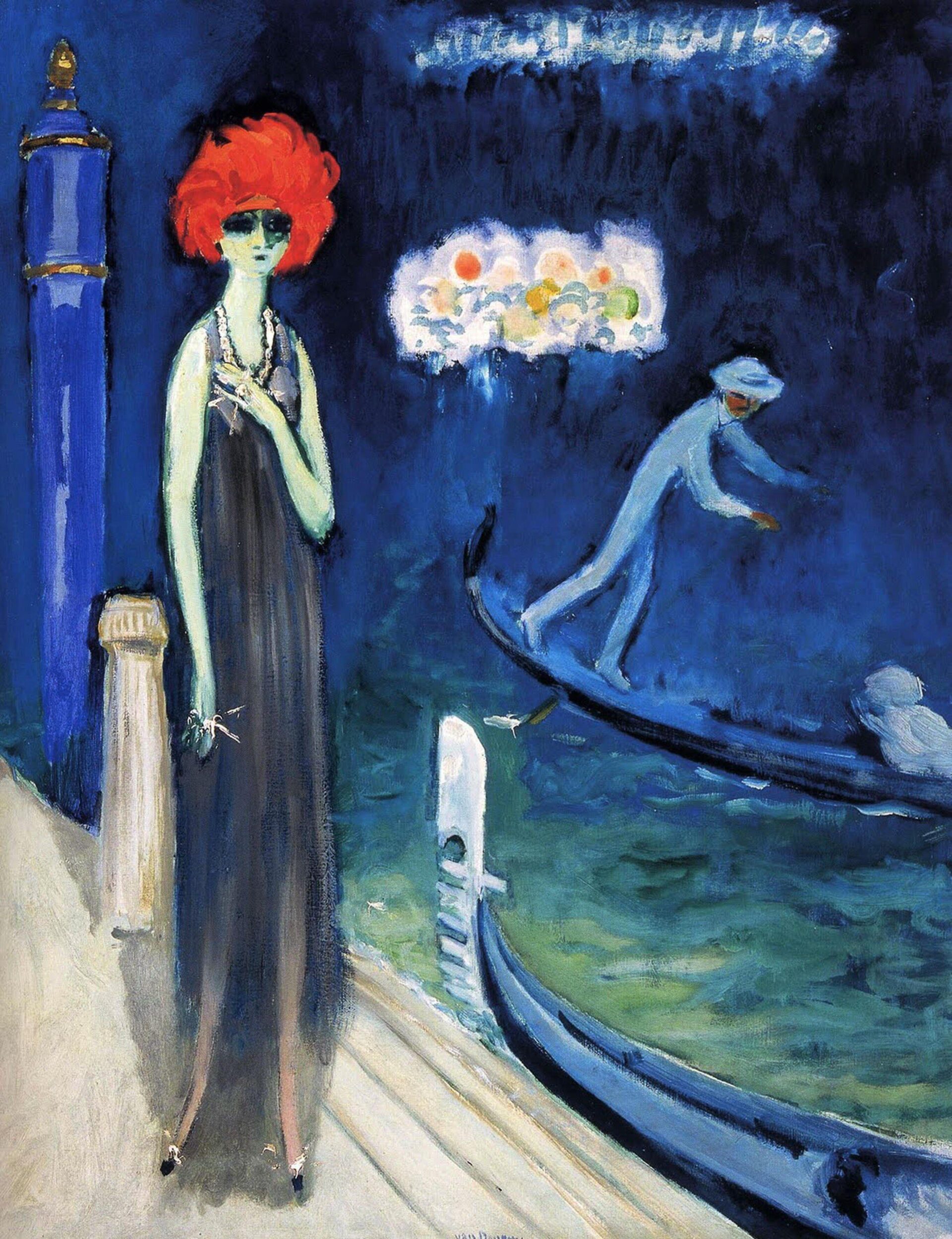

Luisa Casati by Kees van Dongen (1921). The Quai, Venice. Museum: Milwaukee Museum of Art

Casati became a muse to some of the most radical art movements of the 20th century—including Futurism, Surrealism, and Dadaism—and Jack Kerouac once wrote of her: “Marchesa Casati / Is a living doll / Pinned on my Frisco / Skid row wall.” But she wasn’t content to be merely admired; she actively curated her own myth, commissioning over 200 portraits and sculptures as part of the living artwork that was her life.

Generations of artists, designers, and writers have drawn from this legacy ever since; she was “a prism casting its reflections into our time,” as Harning puts it.

Cartier’s iconic panther jewelry was inspired by Casati’s love of wild animals and her piercing green eyes. Her flair for theatrical excess resurfaced in John Galliano’s 1998 couture show for Dior, with rich velvets, feathered headpieces, and touches that could have come straight from her midnight walks through Venice. Alexander McQueen’s 1997 Givenchy collection echoed her obsession with the macabre, while Karl Lagerfeld’s 2010 Chanel Cruise paid direct tribute—models drifting down the Grand Canal in Casati-inspired silks and shadowed eyes.

When the Marchesa decided to move to Capri in the ‘20s, it was nothing short of a spectacle that landed at the island’s Marina Grande.

Casati with painter Boldini and another friend

“When she arrived, she brought an entire entourage with her. Her large trunks contained life-sized bronze gazelles and snakes in glass boxes. Everything was so unbridled,” Harning tells me. “Her makeup was sweating and running down onto her shoes.”

“She always staged her appearances. She must have planned her arrival at Marina Grande, having sewn bells onto her clothes so that people not only saw her but also heard her,” he elaborates. “She walked around in the heat with her hands on a crystal ball to cool herself.”

While there, she once painted her servant’s entire body gold; he collapsed from the heat and was only saved when her landlord scraped off the gilding just in time.

For Bergman and Harning, the challenge isn’t just recreating Casati’s world but capturing her essence. As part of the exhibition, they’ve designed a soundscape using echo to evoke spatial depth, along with a slideshow of images projected onto glass.

“The room is semi-circular and lined with windows,” Bergman explains. “We want visitors to feel like they’re standing in a cathedral dedicated to her. So we’ve printed portraits on glass and placed them within the panes.”

A guiding question throughout the process, they say, has been how Casati herself would want to be portrayed.

“What is respectful in general—and what’s respectful to her?” Harning asks. “The goal isn’t to highlight the madness, but to show the genius. She’s entirely her own point of reference.”

Anna adds, “We’ve relied on intuition. When we sew, we use old fabrics and buttons so there’s a sense of the era. A feeling of character emerges… Certain things seem to almost develop a body of their own.”

Yet Casati’s life wasn’t without its shadows. Her relentless spending led to financial ruin, forcing her to sell off her possessions and flee Italy. Her final telegram to d’Annunzio pleaded for 10,000 lire (he never answered), and she spent her final years in London, living in poverty—a faded echo of her former self.

Portrait of Casati by Giulio “Lolo” de Blaas da Lezze in 18th-century costume (1913); Exhibited at the “Mostra dei Rifiutati” at the Venice Biennale, Hotel Excelsior al Lido, January 20, 1914

The final figure in the exhibition captures this decline: a “trash costume” assembled from scraps. “She was broke,” Harning explains. “She’d rummage through trash cans, using wrapping paper as details for her clothing. It got to the point where she combined two needs—makeup and polishing her shoes—so she put shoe polish on her eyelids.”

Working so closely with such an eccentric figure—even posthumously—has required Nils and Anna to find their own way into Casati’s world.

“Before I go to bed, I feel like we’re corresponding,” Nils says. “I’ve come to think I have her permission to use her voice. She has to be asked for permission, not judged. Even though she was a circus, a spectacle, you have to think: how do you approach or get close to her without scaring her away? I also believe that, at her core, she was quite shy.”

Luisa Casati Stampa died in London on June 1st, 1957. Her gravestone contains an error—her name is spelled “Louisa” instead of “Luisa.” Beneath it reads the inscription:

“Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale / Her infinite variety.”