Il buongiorno si vede dal mattino (A good day starts with the morning)–and on this particularly frigid day in Clerkenwell, on the eastern nub of central London, the Italian community is out to greet the morning with gusto.

Streams of people emerge from beneath the azure domes of St. Peter’s Italian Church–still one of the biggest Catholic churches in Britain, built for London’s largest Italian community in 1863. Modeled on the Basilica of San Crisogono in Rome, St. Peter’s sits grand on a street busy with Georgian architecture, maverick modern design studios, a Sainsbury’s mini-supermarket, a budget hotel, and a Vietnamese restaurant. The steady flow of families and the elderly in their Sunday bests directs itself onto the Saffron Hill street and through a small door. A queue forms for a tinier lift. While much of a long-held Little Italy is now gone, “the club” is its steadfast red, white, and green flag. Literally: a large Italian tricolor facade frames the front, with “Casa Italiana S. Vincenzo Pallotti” in bold lettering. Welcome to Casa Italiana.

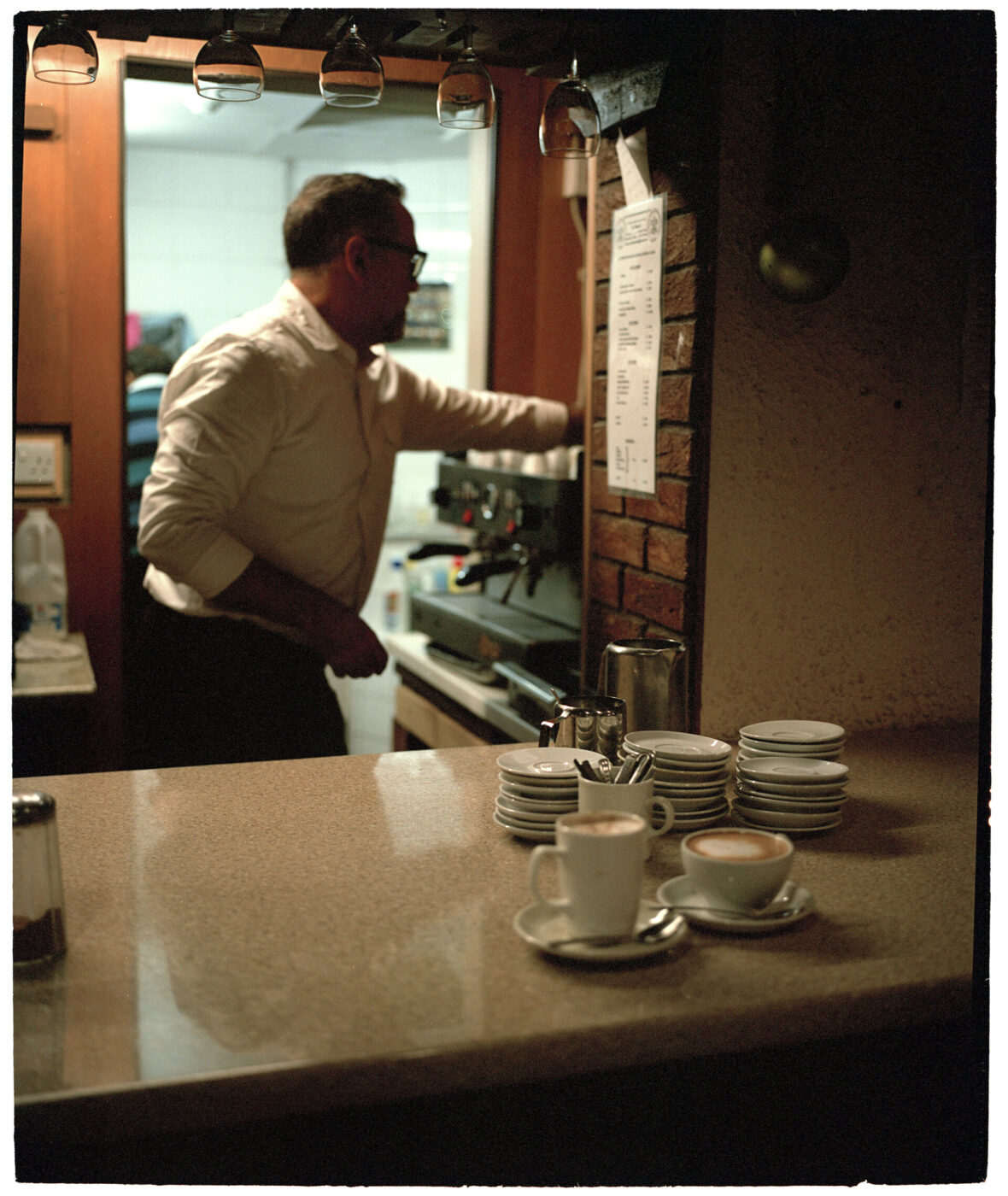

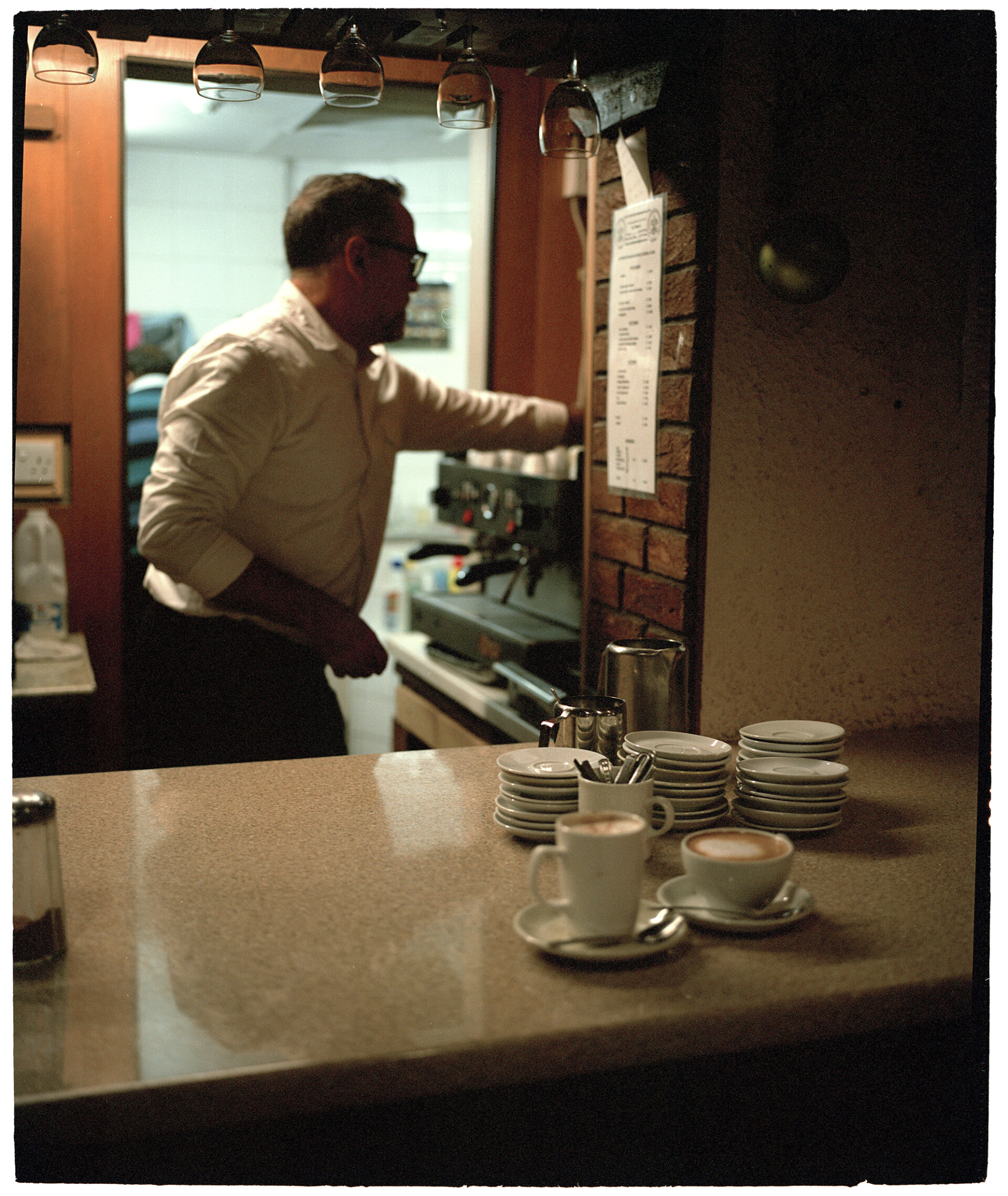

Up the wooden stairs–no time to wait for the lift, the church crowd are gaining and gasping for a cappuccino–and past a solemn Sacred Heart of Jesus Statue is the city’s oldest Italian social club. It’s a bustling hub with a small bar serving coffees and sugar-dusted cornetti, where groups are already slapping down cards in lively games of Briscola. Peroni is £3. Espresso under £2.

The club opened in 1960 as the beating heart of a community of Italians that migrated here after WWII to live in what would have then been a low-income area, finding residence in the surrounding apartments and mansion blocks. Quite a few arrived speaking little to no English. It’s continued to be a space to meet, to celebrate weddings, birthdays, and communions. While London’s skyline heaved higher above it, most of the Italians have been priced out or sought more space in the suburbs–but Casa Italiana is still, for many, a stoic community pillar. And it’s intent on evolving.

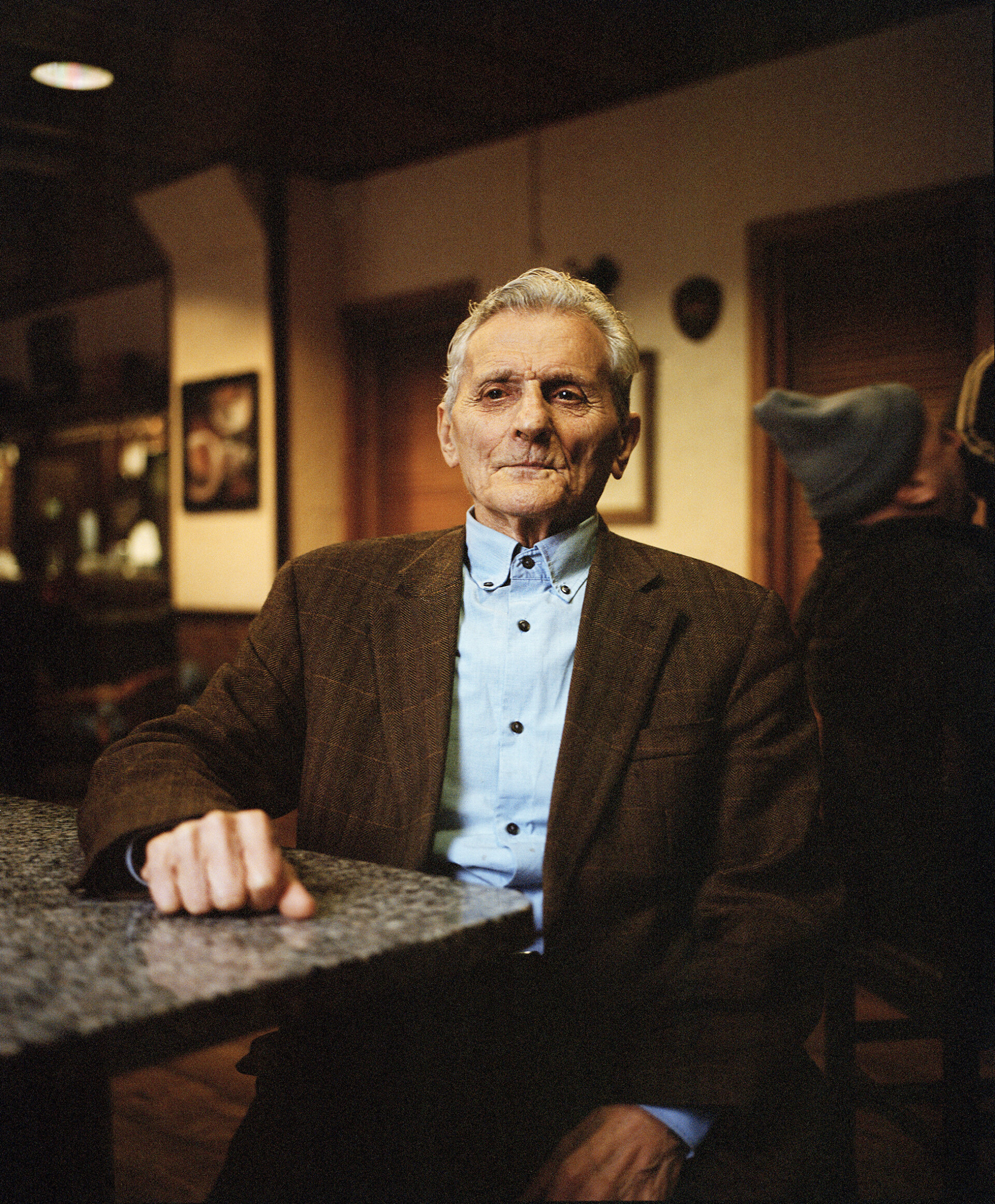

Massimo Pini was born and raised in London. His parents came over from Parma, Emilia Romagna in the 1950s. He’s part of Casa Italiana’s committee, who organize the club’s logistics and events, but he began frequenting the club in his early teens. Sundays revolved around the Casa. “It was our youth club, our hangout,” he tells me. “I met my now wife here.” They got married in the church next door. Pini began to volunteer more seriously around the time of his daughter’s first communion preparations with the volunteer-run kids club, but the pandemic came soon after. Reopening the financially-strained establishment proved difficult. The club went from opening seven days a week to just Sundays. “We huddled together and thought: we need some new blood, to regenerate and open up these spaces to more ideas, activities, and events,” says Pini.

A young Alberto serves us espresso and pistachio cannoli, sweets that come from L Terroni & Sons downstairs–the first Italian deli in the city. He’s a student and a new volunteer. Looking at the Sunday crowd, there’s a real mix of generations and groups. The younger subsection of the Casa Italiana committee started a now regular Italian language bar. It’s become a place for people of varying ages and levels of Italian, and both heritage and non-heritage speakers, who come to the bar for vibrant chat and aperitivo. It’s a key opportunity to excise any shame or shyness for people trying to connect with their Italian identity.

“It’s very Italian to mix together,” says Pini. “Think of a bar in Italy–it acts like the British cafe, or the Irish pub, combined. The bar replaces those spaces as something for everyone. People rock up with their babies in pushchairs for a coffee, older people will have wine and play their cards. I see that as very Italian, and very, naturally, inclusive. It’s all part of our charm.”

It’s also a beautiful time capsule. Wooden panels are lacquered and delightfully mismatched. Crucifixes, football trophies, sashes and flags for home comunes hang on the walls, with sepia, faded photographs of Pellegrino and Bardi in Parma, and the Tuscan village of Grondola. Wrought iron lanterns precede over the bar. When I first visit, Christmas tinsel lines the stocky old fireplace and loops around wicker bottom chairs. Up another flight of stairs–the place unfurls into a bit of a warren–is the winter bazaar. Maialino arrosto, roast suckling pig, is presented in its glory, with thin cuts sliced off and placed in my hands to eat quickly. Porchetta is trotted out in abundance from the stooped kitchen. Caterina, who is in her 70s and originally from Puglia, sells me a hand-knitted burgundy neck warmer with pink buttons while her friends sternly knit more wares. I’m tempted to go back for a pashmina, but a table of Italian cakes calls–a liqueur slick torta amaretti, a rustic ring-shaped ciambella, one crostata studded with plums, and another with lattice marmalade panels. Hefty Christmas hampers filled with Rummo pasta, preserves, and biscotti are up for raffle. Ida, 87, who has been coming for 40 years, flicks through her tickets.

The club is expanding with new events too. In November, Big Mamma Group–the Italian cuisine chain comprising 17 restaurants, including the close by Gloria in Shoreditch–ran a Cena di Natale fundraiser in the upstairs room with a sumptuous four-course feast for guests. In October last year, the club was the setting for a filmed interview with Arsenal’s Italian defender Riccardo Calafiori. So yes, while Casa Italiana seems the quaint, nostalgic vignette of a time past, its touchpoints for its diaspora are growing. “WhatsApp became the way young people connect with each other,” says Pini, “but I think they want something really genuine and tangible. That’s something you can feel in the walls here.”

Efforts continue at the same time to keep its integrity and community feel. “We want everything to continue feeling like it’s available and accessible to everyone,” says Pini. I visit the club again on a Tuesday when they run a weekly lunch club primarily for the older patrons. Pietro Molle organizes this circolo della terza eta–“the circle of the third age”, in English. “It’s a chance to meet for a few hours as if in Italy again,” he says. The head chef is Donato Guidi, who has cooked at the club for 15 years alongside his full-time chef job in a London restaurant. For £10, we receive a primo of a simple tomato rigatoni, a chicken secondo, piece of fruit, and a (several times refilled) glass of wine. A bouquet of ciabatta sits on every lace-covered table. Volunteer servers in tabards ladle out seconds easily when asked. When Molle finally eats, there’s a well deserved extra helping of sugo on his pasta.

I’m seated with Lara and her husband from Cagliari, Sardinia, who moved to London in 2004 to be closer to their adult children and grandchildren. Vittoria is also beside me; she’s from Rimini and lives in Ealing. She says she barely spoke English when she came over as a young woman, and we talk at length about Italian pop music, shopping, and good coffee. “This is the only time I will come into the center of London,” she says, redoing her coral lipstick after our primi. “It is something to have in my calendar. I like to dress up, have somewhere to sing!” The ladies and gentlemen here, all aged 70 and above, are dressed slick and smart. Lara barely sits, moving from table to table to charmingly drum up more raffle tickets and shake her money belt. The tombola is announced and a lady at the table opposite wins a chocolate-studded panettone, which she holds aloft. Vittoria spreads a box of Venetian chocolates she bought at the deli across the table, dropping more into my handbag.

Then Pietro starts the music from his laptop, and the dancing begins: the tango, the waltz, the tarantella–the frenetic folk dance that finds its way from Calabria to Puglia. Servers weave through the sudden dancefloor frenzy to stack plates. “Amor Dammi Quel Fazzolettino”, by the Piacenza and Parma 80s group I Girasoli, really gets things started. The bouncy accordions of El Canfin rouse the crowd too. I dance with Guiseppe, who is in his 90s and wears a full three-piece navy suit. He drives in from outside London every week. I dance with Alfonso too, in his 80s, who only breaks to have a go on the harmonica and chide me for trying to lead. He keeps his tinted sunglasses on the whole time, and snaps his braces to the rhythm when he decides to solo dance. The nostalgic music ends and we finish with the British and Italian national anthems in succession, to which everyone stands and sings passionately.

“One guy is over 90 and a keen gardener,” Mario Zeppetelli tells me, “and he always brings something from his garden for his favorite people–one being my wife! Another guy always gives her fruit pastels.” Zeppetelli and his wife Sue began getting more involved after their own retirement.

“Everyone has their role,” he says. “One lady, Paula, has her one job: plastic glove on, put cheese on the pasta. Lara does the money. Others do the dishes. I try to help, but I’ll not get in the way. It’s a regimental army here and it works! If I was to try to put the cheese on? That would be it!”

Zeppetelli has been coming to the club for as long as he can remember. He was born in Sicily to a Sicilian mother and a father from outside of Naples. “He was a clarinet player, and he would play for the saint’s festas, travelling around to play music with his bands.” The band went to Sicily, and he met Zeppetelli’s mother there. His parents emigrated to London first while he was a baby to get settled, find jobs and a community, and sent for him a year later to live permanently. The club was foundational to their new lives.

“I used to come down from Islington almost every night with my friends. In the ’70s, it was thriving seven days a week,” says Zeppetelli. “I’d help behind the bar as a teenager. I lost touch in the ’90s when our kids were young and my mum was unwell. When she passed away, I decided to come back and help as a volunteer. The club had just been through COVID and congestion charges had it on its knees. I just did not want it to close down. Me, Massimo, and other volunteers joined the committee to move it forward and keep things above water.”

He recalls the Sunday formula infinita: church, a mortadella pick-up from the deli downstairs, a Coke and a coffee in the club. “I grew up in the club, my parents trusted I was safe here. It was a safe space for them too.”

“People get upset when we have the summer and Christmas breaks,” he says of the lunch club. “We’re expecting a full house this week.” They’ll be continuing the Befana celebrations with a special four-course menu. Zeppetelli says they hope to have Friday and Saturday evenings up running soon–a chance for young people to gather for aperitivo before they head into town.

A new (first, second, and third) generation of Italians are finding their way to Casa Italiana. Fiorenza De Filippo, 27, from Foggia in Puglia, first saw the club when it was featured in a campaign for the fragrance brand Ffern’s Summer 2024 campaign, which was inspired by the Tuscan landscape and Italian oranges.

“Visually, it spoke to me,” says De Filippo. “It just resembles somewhere you would walk into in a random place in southern Italy. It felt familiar, instantly. It answers the need of a space that isn’t a restaurant or bar, which in London doesn’t exist much.”

“There’s a layer of identity to it for me too,” she adds. “It’s a space where I can be surrounded by Italian culture without thinking too hard about it.”

First walking in, she didn’t know what to expect. “You’re entering a community that has existed for a long time,” she says. Was tradition ready to be transcended–should it be? Visiting on Sundays and becoming more involved in the committee alleviated any worries. “The club exists as a lot of small clubs within the club,” she explains. “The challenge continues to be, ‘let’s understand who we are and what we want to do out of here’. That community building is still at the forefront. We are creating a new group that didn’t exist before, and that comes with its challenges.”

De Filippo is now regularly involved with the club and its younger committee. She often visits with her English partner. “He has the opportunity to not just learn the language, but to get really deep into Italian culture and its unspoken ways,” she says. “How we express ourselves or set boundaries, for example. It has helped him understand me, my family, and where I come from.”

“What I have loved is meeting second and third generation Italians,” she says. There are fewer first generation, young Italians, but it gives her an opportunity to become more curious about the way in which Italian culture shapes itself in the UK, as articulated at the club. “I’ve got to observe little bubbles of dialects that have interacted with cockney accents that can really only exist here,” De Filippo says. “Then, some dialects that have preserved themselves in the club with words that don’t even exist in Italy anymore!”

More people continue to venture through the doors and find affinity here. “There is, say, a woman who has married an Italian person and is now raising an Italian child,” De Filippo tells me. “It’s important for her to have her child socialized in Italian culture, but for her to also learn more. Then there are people who had Italian parents who are now gone, who never got a fair shot at ‘being’ Italian–it was less ‘cool’ in the past to be Italian, there was a stronger desire in the past to look and present as British. That’s very different now. It’s very beautiful.”

“We need to keep thinking about the needs of this space, and how it will fulfill people. Sometimes it’s about holding onto culture and coming closer to an identity, and sometimes, it’s just about making new friends.”

There is an expansive, ongoing dialogue about Casa Italiana’s future. There’s work to conserve its delicate ecosystem, a place of history and entrenched community. But there’s also a need to both breathe new life and bring new meaning to the space, for incoming generations to continue its story. The club is in a brilliant period of flux. For one, De Filippo is organizing a new ticketed supper club with a London chef, which will have a changing seasonal and regional focus with each event.

“For many, it’s the one time a week that they get dressed up and go into town,” she says. “We have to make sure that people who have appreciated this club for decades can maintain their seats at the tables. And I want to sit and get to know them and their stories too. Fill the wine, have a dance.” Just make sure you get in before the after-mass rush.