The first time I heard Popa’s “Tocco di Lusso,” the soft strains of the opening notes, the whimsical lyrics (“Guardi lo specchio e dici, ‘Wow,’”) I felt that I had finally found the kind of music that resembled the soft girl rock I listened to in the United States but with an added bonus—a sort of unearthing of the Italian language.

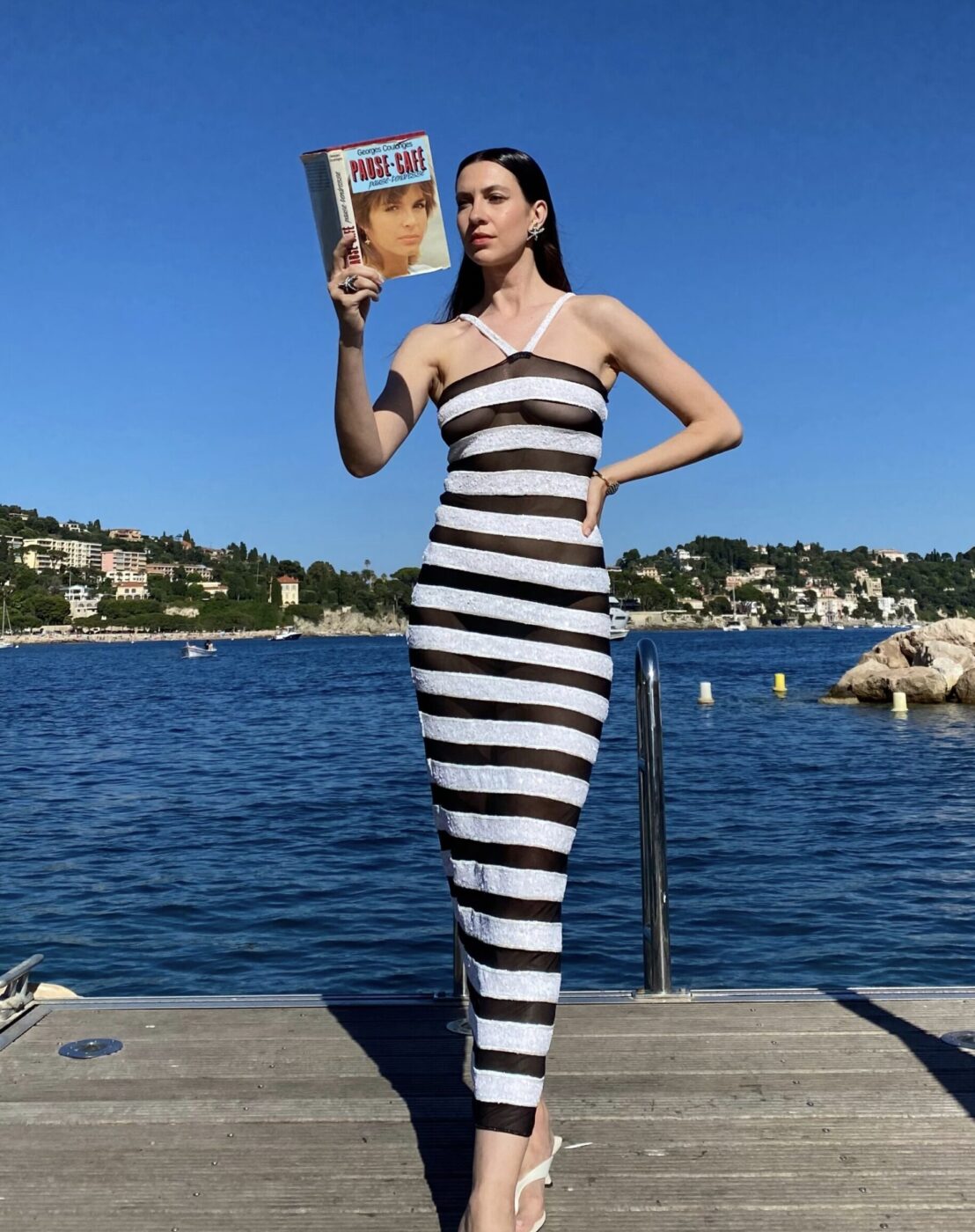

At the time, I didn’t know that Popa, or 34-year-old Maria Popadnicenko, was born in Lithuania and had only moved to Florence at 18 to study fashion design at the city’s Polimoda. Something attracted me to her discography, ensuring that I would heart almost all of her songs on Spotify in quick succession. Perhaps I had instinctively noted a foreigner’s eye towards Italian culture, an outsider observing the country’s patchwork of details. Walking with a friend to get gelato, I recounted to him the lyrics of Popa’s “Sciura Milanese,” which sketches a detailed image of the elegant women of a certain age that haunt Milan—appointments at boutiques, pasticcini at Sissi, vacations on Saint-Tropez. At one point in the song, Popa stops to address the sciure directly, noting that “one day,” she “would like to be just like” them.

“She gets me!” I told my friend excitedly—he knew I was always saying that middle-aged women in Italy were my fashion icons. “I would totally stop a sciura on the street to tell her how amazing she is!”

But what really sets Popa’s music apart is the style, more reminiscent of the soft, almost melancholy, indie girl rock of Clairo or Men I Trust than of the major female names in Italian pop, like Annalisa and Elodie. There is an intentional nostalgia that tinges Popa’s work and a certain evocativeness—most of these songs are full of proper nouns, like images pinned on a mood board before a fashion show. (Some examples: “Il tuo chalet a Courmayeur” / “Your chalet at Courmayeur” from “Bon Vivant,” “Il calendario dei miei amori edito da Rizzoli” / “The calendar of my loves edited by Rizzoli” from “Psicomagia” or “Facciamo un bagno nel caviale, guardando Bosco Verticale” / “Let’s take a dip in the caviar, looking at the Bosco Verticale” in “Tocco di Lusso.”) These are references stacked on references that create a meta-world for each song.

None of this is so surprising, considering Popa’s past as a fashion designer for storied brands like Max Mara and Emilio Pucci. In fact, her music career happened largely by chance, after she decided to leave her role at Pucci and go out on her own. Inspired by her music producer ex-boyfriend and an itching desire to try a new artistic pursuit, her first few songs came together with input from her Milanese circle of creatives. And while she doesn’t think of her musical endeavor in terms of success, we may give her one accolade: she recently performed her first gig outside of Italy, at Budapest’s Sziget Festival.

We sat down on Zoom with Popadnicenko to discuss her music, her sources of inspiration, how she came to Italy in the first place, and just what makes the “Sciura Milanese” such a compelling subject.

IS: How did you begin your musical career? Was there something in particular that inspired you to create music?

Popa: After I worked in fashion, at a certain point, I felt that I was missing something. As a fashion designer, I was designing collections and it was always the same thing. I felt that I had something else to give and that I didn’t want to work only in fashion, always as a designer that goes from one season to the next.

I remembered that, when I was young, before I began studying fashion, I had done dance, I had also made music, I painted—I liked to do different things. When you become an adult, you have to choose a direction. But after I had worked in fashion for a number of years, I felt that, in the end, I couldn’t do just one thing. How could I expand my creativity?

So I left my full-time job at Emilio Pucci in 2018—I had already moved to Milan. I’ve learned in life that, when you want to do something different, you have to eliminate something. You have to find space. When I left my full-time job, there was a space that I had to fill. At that time, I was with a producer, Gaetano Scognamiglio, and he had his genre that was very of the ‘60s and ‘70s—he collected vinyl, and I was really surrounded by this music, in the car or at home.

I absorbed everything. When you’re not Italian and you decide to live in Italy, you’re almost like a two-year-old. Everything surprises you. In Lithuania, this kind of music didn’t exist. And being with Gaetano, at some point, I said to him: I have an idea. I want to write a song. And the first song was “Sciura Milanese”—I thought, if I had to write a song, what has really stuck with me the most about Milan are these women.

Italy Segreta: What first brought you to Italy?

Popa: My sister was already living in Italy, and I came to visit her when I was 15 and I understood that I had to be here, that I had to live here. I got to know the country through the music, through what was on the radio, like Ricchi e Poveri. My parents used to put on music from the ‘70s and it really stuck with me—I thought, I want to understand this language. But even though I didn’t know that, one day, I’d make music–even without being conscious of that fact–it was art that led me to Italy.

IS: What were your first experiences like in Italy?

Popa: When I moved here, I finished high school in Lithuania in June, and then I packed my bags; I was already in Italy by September. I was 18 years old, and I came to study fashion at the Polimoda in Florence. I wanted to become a fashion designer.

Florence is a city with so many international people. I didn’t speak Italian, but my circle of friends were mostly international people with whom I could still speak English. But I was surrounded by Italian Renaissance architecture, and it was truly a dream to study in Florence. And I began to get to know Italians, and they always encouraged me, saying, “Good job, you’re already speaking Italian,” even if I managed to say just two words. They were really welcoming.

Eventually, I went to live in Reggio Emilia for my first job at Max Mara. It wasn’t international vibes anymore—the office was all Italian and almost no one spoke English. I had to speak with my colleagues, with suppliers, with the atelier—I had to express myself and explain my ideas. Max Mara is famous for taking on foreign designers, and we were truly the black sheep—we all had culture shock.

IS: How did you begin to understand Italy?

Popa: It took 10 years for me to really understand Italy—all the musical references, to really go deeply into the country. I already lived in Italy, and I was already spending time with Italians, but I wasn’t getting the jokes or the regional accents. It took so much time—I always felt welcomed by the Italians but, at the same time, I knew I was a foreigner.

IS: One of the reasons we’re talking today is because the theme of our upcoming issue is Milan. I thought of you immediately because of the song “Sciura Milanese,” especially the part of the song in which you talk about your desire to be like these women one day. Could you tell me a little bit about how you wrote this song and why you chose La Sciura Milanese as a concept? What does the sciura represent for you?

Popa: It always impressed me—these really beautiful women who were older, how much they took care of themselves, how beautiful and unusual they were. In Lithuania, dressing well and putting on a pearl necklace or makeup is almost considered a vanity. It’s the opposite of Italy, which is all about showing off and being tanned. In Lithuania, if you’re wearing something more luxurious, everyone asks: “Are you going to a party?” And here in Italy, if your hair doesn’t look good, they’ll say: “Girl, it’s about time on Sunday to go to the hairdresser and get your hair done and dress up.” It really struck me that, at that age, you’re 70 and you almost look better than a 20-year-old girl. I really liked the idea that life goes on, that it’s not like when you get to a certain age, there’s no life for you. In Lithuania, it’s also about the country’s economic state—there were no sciure because of the Soviet Union. After [the collapse] of the Soviet Union, there was no wealth.

When I moved to Milan, I found all the places where the sciure would go—these were the trusted spots, the trusted hairdresser, the trusted bakery. I learned from them how to take care of yourself—I only went to the places where the sciure went, where the waiter knows you, where there’s that kind of old-school treatment. For me, it was also a way to understand where the sciura comes from and what Italy was about and what Italy was like 30, 40, 50 years ago.

So with the sciure, I came to Gaetano and I said: I want to talk about what the sciura does during the day, the pasticcini, the hairdresser, the beige coat. I wanted to talk about how much I admired these women and how I wanted to be a little closer to who they are.

Photo by Sciuraglam

IS: How did you start to have success with your music?

Popa: I had my songs, “Bon Vivant,” “Sciura Milanese”, and “Tocco di Lusso” ready to be released, but then the pandemic happened. These songs were not really in line with the moment we were living—they were too joyful, mentioning Bellinis, martinis, jacuzzis, and bikinis.

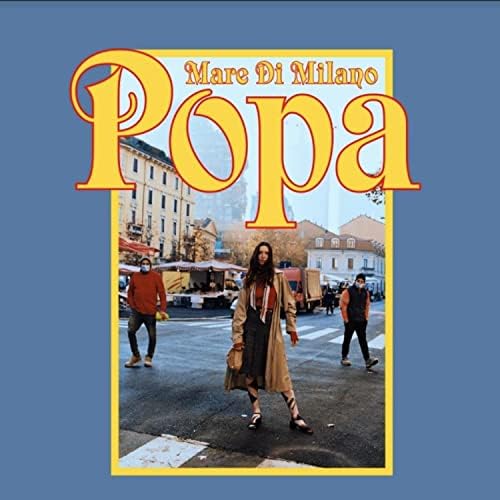

It was at that moment that I met Victoria Genzini—I had known her for many years, but she lived in London and then she came to live in Milan. And I was like: I have this song and I want to release it, and she said that she had this Google Drive with some lyrics, and one of them was “Mare di Milano,” about this improbable love in the time of the pandemic.

They were simply lyrics without a melody—it was more like a poem. And I was with my producer, my ex, and I just started singing these words and then he went to the piano and we made the song. It was perfect for that moment, and within three weeks, we said, Let’s just release it.

From there, we wrote “Psicomagia,” about tarot reading and astrology, and we made a music video. There were so many creative people—we just bonded during this zona rossa [lockdown]. After “Psicomagia,” I was like, Okay, the pandemic is finished. Finally, I could release my songs that I had kept to myself all this time. And then we released “Bon Vivant,” “Tocco di Lusso”, and “Sciura Milanese.” It all started from Milan and being in love with the city and the synergy of creative people. There were so many different artists that somehow contributed to the styling, the set design, the directing. These coincidences all happened at the right time.

We uploaded the song to an app; we didn’t even have a label. More than anything else, it was word of mouth. It all happened very naturally. I don’t know if I can call it a success—I still feel like that day when we released “Mare di Milano.” But of course, there are more concerts, more live shows, and I’m invited to play gigs. But for me, in the end, the important thing is to observe. I want to be inspired. I’m not really interested in the success side. I want to follow the inspiration.

“Mare di Milano”, Popa's song about improbable love during the pandemic

IS: What inspires you when you write music?

Popa: What I want to do is be creative, and I look for positive inspiration, but there are also painful moments in songs, a little bit of melancholy, a little bit of heartbreak, but told in a nostalgic way. There’s nothing bad about feeling down—I’m very emotional, very sensitive, so I like my songs to be a mirror of this type of Italy. There is a little bit of the ‘60s and ‘70s—that everything is a little bit of a dream, that it’s not very down-to-earth, it’s like an escape from reality. Today, we really have our feet on the ground with our problems, our daily lives, our anxiety, there are so many things to complain about. But I’m always trying to find another dimension, to live and dream and see things from another angle, a little bit more emotional, lighter, but not in a superficial way.

IS: Is it challenging to write songs in a second language? What is difficult and inspiring about writing songs in Italian?

Popa: I am very embarrassed to admit this, but I never studied the Italian language. I learned it on the go through simply living here and hearing people talking. I often create my own ways to say things in Italian, which are not necessarily the common and usual ways of saying something but can still be understood by Italians and non-Italian speakers.

Sometimes, it can be very challenging for me to express my thoughts and ideas in Italian. I still think in Lithuanian. But at the same time, the fact that Italian is not my mother-tongue language allows me to come up with more unexpected storytelling in my songs. My lyrics always come from an observation, through simply analyzing the Italian way of living and what people talk about on a lazy afternoon in an Italian piazza while drinking espresso. I like to start from one or two words that become the main theme and then build a story around it.

IS: I know that a lot of journalists have already asked you this, but it seems like an important question given your career. How do you see your experiences in fashion and music as connected? In both fields, do you have a similar creative process?

Popa: Fashion and music—again, it’s art. The thing that I’ve noticed with fashion is that, if you want to be truly creative and express yourself, it’s very difficult to put it out there. You need to really create a collection and you need to sell. At the end of the day, it’s really a business.

Music is also a business, but with music, I felt a little bit more free, like there was less pollution. It’s the same process. If you need to design a collection of 10 looks, you do the research, you pick all the ingredients, the fabric, the color, the style, the theme, the inspiration, the mood board. You think of who you want to dress and who is going to wear your clothes. It’s the same with music—you think of what kind of mood you want and what kind of instrument can translate that feeling. But with the final result, with fashion, you have to actually physically make things. You need to sell it if you want to make a living. With music, you put it out there and people can connect to it. It gets into their hearts faster. But at the end, the creative process is totally the same.

IS: How would you define your musical style? I find that there’s a certain type of Italian pop, let’s say, like Annalisa and Elodie, that is really widespread, but your songs instead are really soft, elegant, a style of Italian music that you can’t find everywhere.

Popa: I’m very indie, a mix of Phoenix, Tame Impala—these are my idols. But at the same time, I also like pop music. ‘70s music is in my blood—but I don’t want to make vintage songs. I still want to translate these songs with a contemporary vocabulary, mixing ‘70s and ‘80s music with indie. I think about it a little bit like a luxurious indie, what you listen to when you’re relaxed, like a rock band on a boat, everyone dressed nicely, or on the steps of a church like Santo Spirito in Florence.

Sometimes I call it “pop di lusso,” but people misinterpret that. When they hear “lusso” [“luxury”], they think it’s about wealth or money or a good car or an expensive house. For me, “lusso” is like allowing time for yourself and enjoying the moment with your friends—when you’re healthy, when you’re calm. This, for me, is “lusso.” It’s that idea of watching Selling Sunset, something mainstream, but with a silver tray and a teacup. It’s easy-going but also something that has value.