The year’s most delicate weeks for a sourdough pizzeria arrive not under the heat of a summer rush, but in the early fall, when the flour from the year’s wheat crop arrives. “The grain is harvested at the end of June and beginning of July,” Matteo Aloe, co-founder of Berberè pizza, explains. When the first bags from the new harvest reach the pizzerias, it’s “kind of a scary moment,” he says. “Every year, every batch is different. Like wine.”

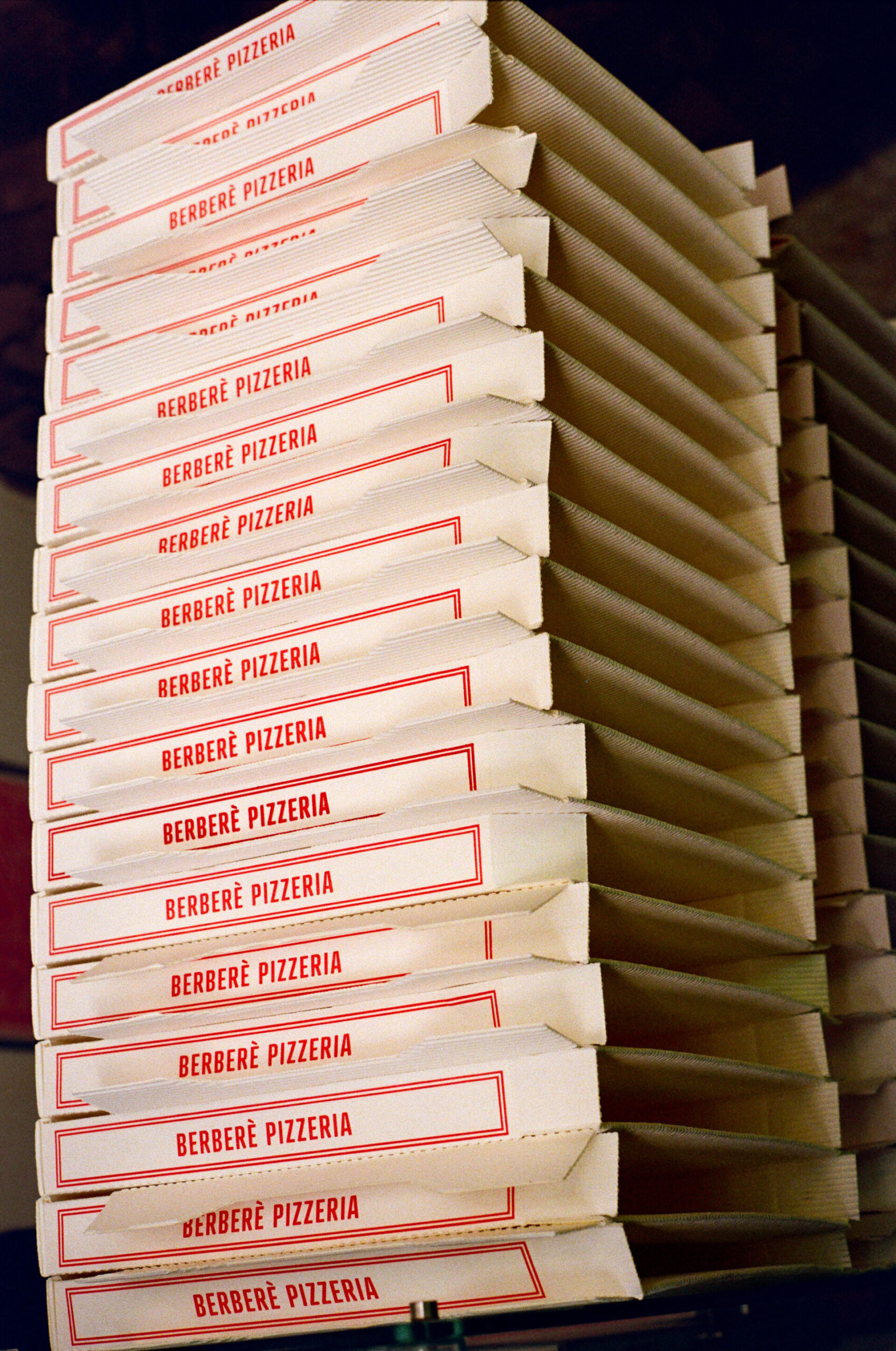

Aloe and his brother Salvatore opened Berberè 15 years ago in Castel Maggiore, just outside of Bologna, and built a following not by imitating Naples or Rome but by rethinking the pizza chain from field to oven. In those days, Italy’s casual dining world was far less interested in the details of flour and fermentation, but their idea was to change the way pizza was perceived in Italy by focusing on heritage wheat varieties, sourdough, and organic, short supply chain toppings. With 21 locations across Italy and four in London, it’s safe to say they succeeded.

Matteo Aloe behind the pass

The brothers opened the first location in the mall because it just made commercial sense… and then proceeded to do things that did not. They refused the most obvious sales driver: “We decided to not sell Coca-Cola,” Aloe recalls. Customers came expecting the usual from an Italian pizzeria—200 seaters with TV screens streaming football matches—and instead found type 1 flour, organic tomatoes, no soft drinks, and a more designy look. “For the first three months at least, they were leaving,” Aloe says. Some families barely glanced at the menu before turning back out the door.

And yet word spread. Aloe still remembers a man with yellow glasses who appeared one evening, then again the next, and the next—four nights in a row, each time bringing friends. “He came with more people every day,” Aloe says, “and finally I worked up the courage to ask why. He said, ‘This is fantastic, so I’m telling everyone I know.’ That was the moment I realized, ‘Okay, let’s keep calm.’”

The deeper validation came a few months later in Naples, where their sourdough crust, lighter and tangier than the thick, fast-fermented pies many had grown used to, struck an unexpected chord. A local man took a bite and surprised him by saying “‘Oh, this tastes like the pizza I used to eat when I was a kid.’” For Aloe, it was confirmation that Berberè’s experiment was not a detour from tradition, but a re-discovery of how pizza once tasted before the norm became shortcuts—“products from cans” and “dough made with supermarket yeast one hour before serving.”

Berberè’s is a much lengthier process, one that begins in the wheat fields of Emilia-Romagna. “Together with our business partner Alce Nero, we grow 100% organic wheat through a cooperative of farmers,” Matteo tells us. “We know, today, organic doesn’t always mean good in terms of taste, but if [the wheat] is certified organic, you’re sure that this soil will survive in the future.” They also practice crop rotation, giving the fields rest years—leaving them fallow or planting legumes—to ensure the soil’s nitrogen can be replenished. “It, of course, costs more, at least double, to produce less. But it’s the only way…to preserve the soil for the future.”

Aloe points to ancient wheat varieties that were taller, with deeper roots that could access nitrogen in the soil without sapping it; modern dwarf wheats, shorter and bred for uniformity, rely more on chemical fertilizer. That shift, he argues, didn’t just alter farming practices, it altered the grain itself. “In the past 50 years, the protein in the grain has changed and a lot of people have become intolerant to gluten, not because of the gluten itself, but because we changed the structure of this protein.”

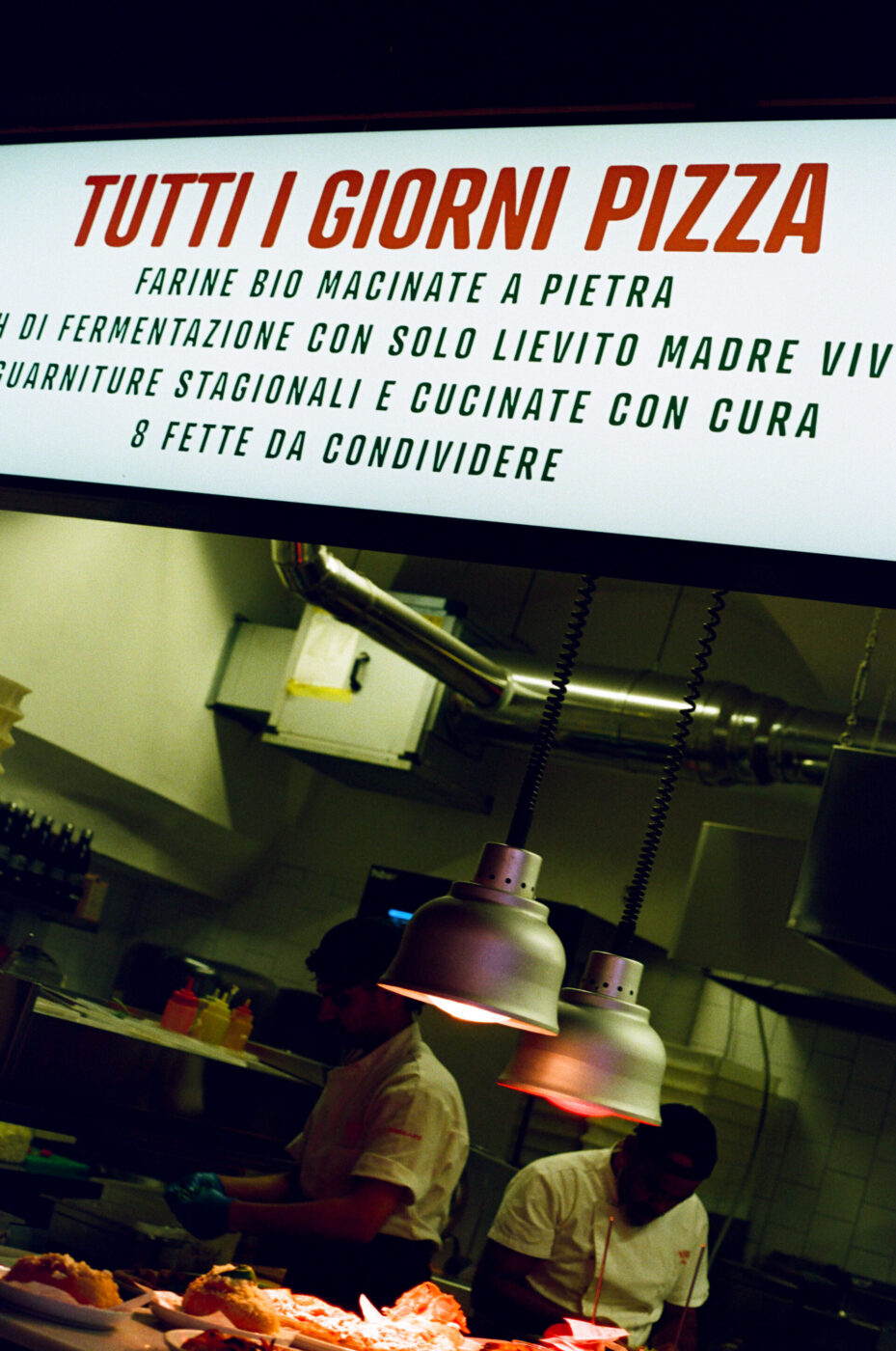

The next choice—how the grain is milled and how strong the flour is—was also made with digestion on the mind. “Type one, never 00,” Aloe says, emphasizing a semi-whole or stone-ground flour that retains bran and germ rather than a refined powder stripped of nutrition. He also avoids the ultra-strong flours many pizzaioli use for dramatic lift. “We use 260,” he explains, referencing the W index that measures flour strength and elasticity. Lower strength ultimately makes the dough easier to ferment, easier to digest, and less theatrical (you don’t get those Insta-favorite air bubbles)—but more pleasurable to eat.

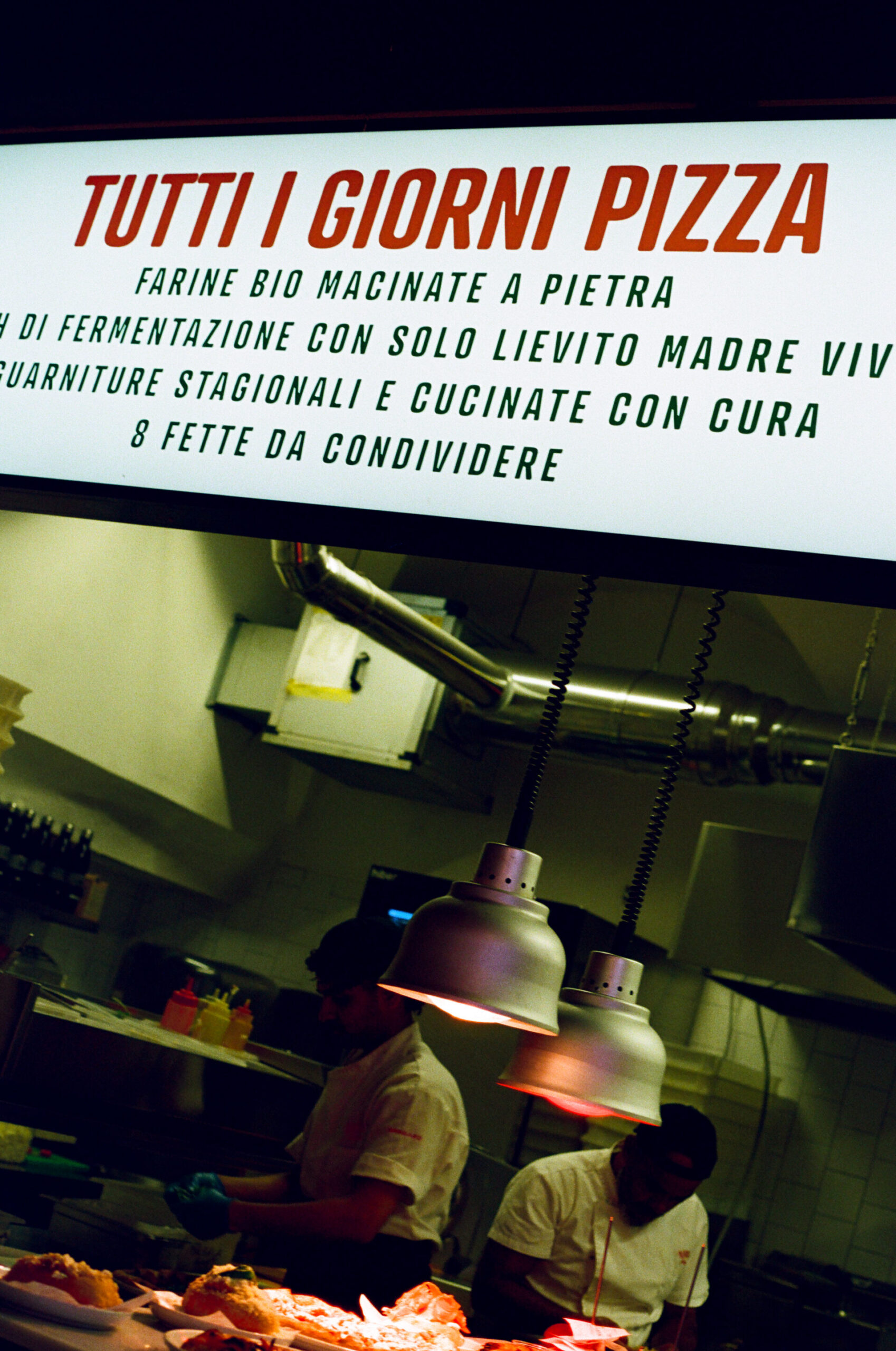

Then comes fermentation. Sourdough is not yeast from a packet but a culture of wild yeasts and bacteria that, over time, digest the flour’s starches and proteins. The result is dough that rises slowly, develops acidity and flavor, and becomes easier to digest once baked—but that’s also incredibly sensitive to environmental changes, whether humidity, temperature, altitude, etc. “We do 24 hours of fermentation, so it’s really important to control the whole process, and we do a lot of timing, measuring. It’s an artisanal process, but with technique.”

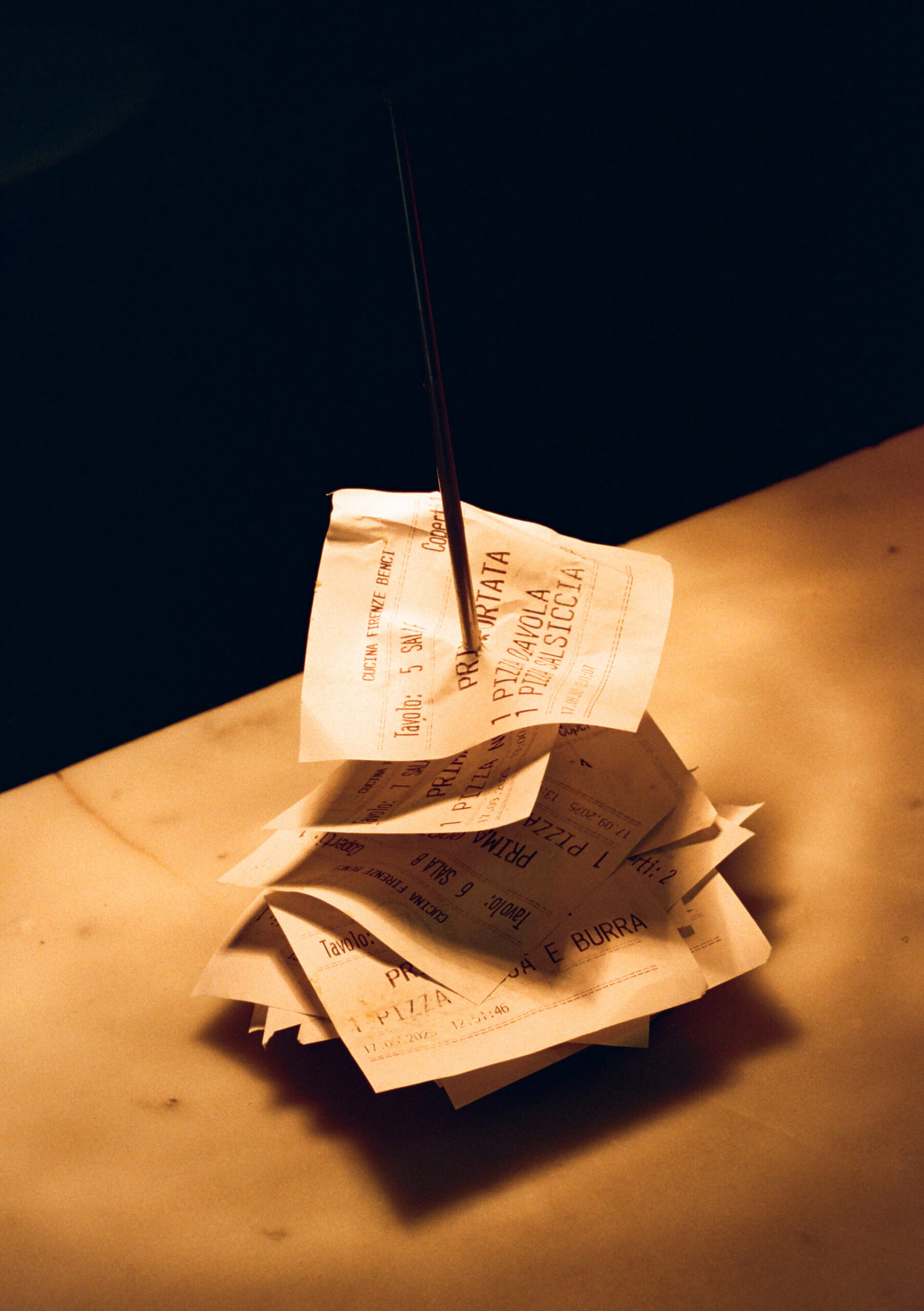

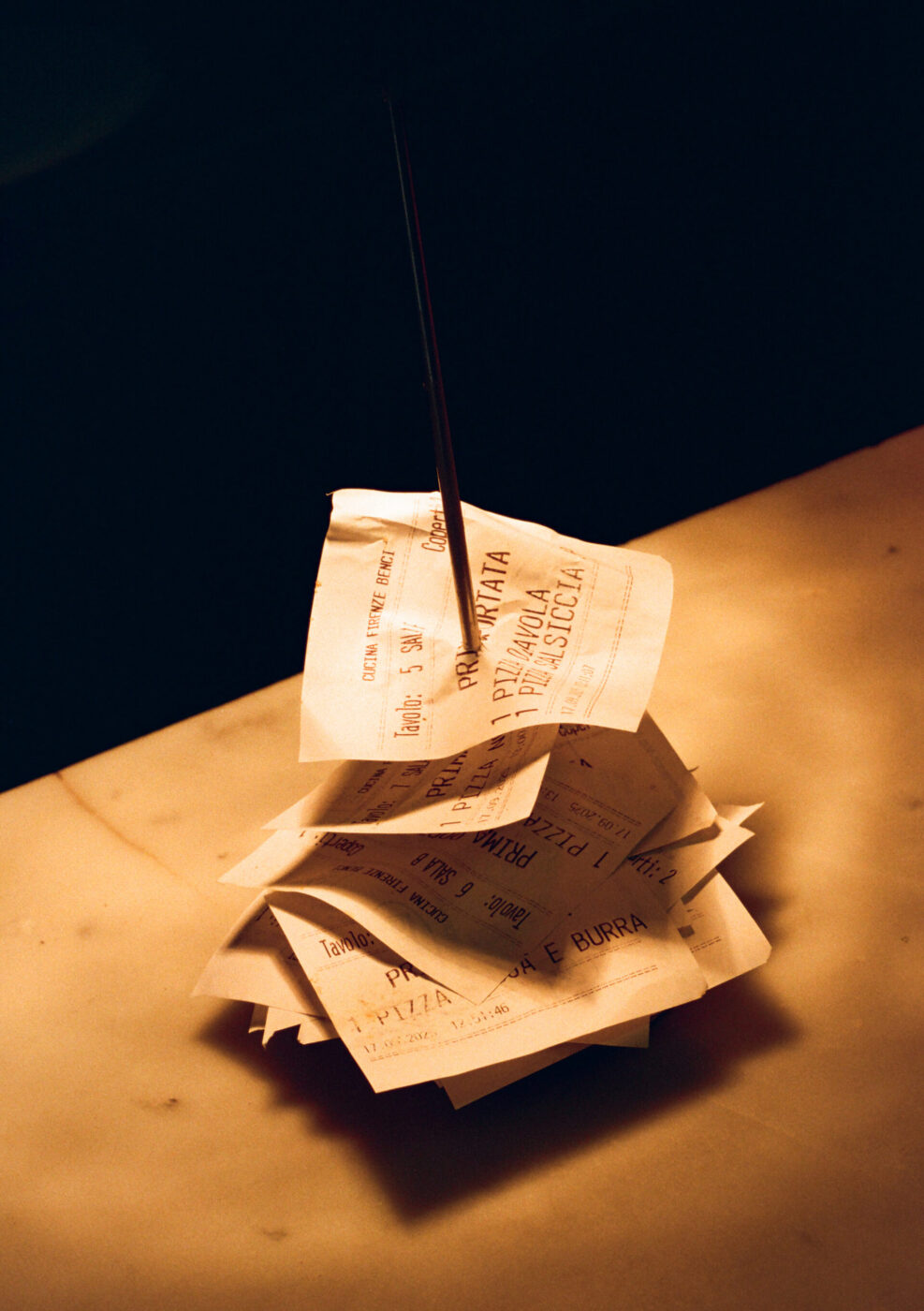

Every pizzeria keeps records—dough temperature, water percentages, proofing times—shared back to Bologna in real time. Aloe pulls out his phone to show an endless scroll of WhatsApp groups, one for each Berberè location, with bakers posting daily photos of dough and log sheets. Before any new batch of flour reaches the wider network, it’s tested in Bologna and adjusted. “We say, ‘Okay, add 1% of water. Remove 1% of water’ because every batch is a bit different.” (Plus, a Roman August is not a London February, and dough responds to both.)

Training happens at Casa Madre, a hybrid pizzeria, classroom, and bunkhouse that opened last year in Bologna. Upstairs are offices and eight beds for visiting members of the team; downstairs, a live line where new teams for openings spend six to eight weeks. “We call it Casa Madre—like lievito madre—because it’s where we ‘make ourselves.’”

If the upstream pieces sound technical, the downstream goal is one that anyone can get behind. A Berberè crust “has to be a little bit crispy, a little bit soft,” Aloe says. After dinner, “you have to feel well. Not super heavy for the whole night.” In practice, that means a texture that holds a topping without flopping, with edges that crackle and an interior that springs back, more New York than Neapolitan in the bite.

Today, Berberè is expanding in London, which Aloe believes is “leading a new wave of pizza.” Who knew that a small mall bistro on Bologna’s outskirts would make it to one of Europe’s most competitive cities, but, as Berberè office motto goes, “The future is unwritten.”

What is written is that “we care about the product and we care a lot about our people,” says Aloe. And, in the end, that is the through-line from field to forno: a chain of farmers, millers, bakers choosing depth over convenience.