Even if you haven’t seen their movies, you’ve at least heard of directors like Rossellini, De Sica, Antonioni, Fellini, Pasolini, Bertolucci, Sorrentino, Moretti, Bellocchio, Tornatore, Martone. What do they all have in common? They’re male directors, and the undisputed protagonists, award-winning by critics and viewers, of the cinematic world from the postwar period onward. But what about Lina Wertmüller or Liliana Cavani (who just turned 90), or more recent voices like Alice Rohrwacher, Emma Dante and Susanna Nicchiarelli? Besides being clearly in the numerical minority, female directors’ names do not have the far-reaching recognition of their male counterparts–historically, a product of the political and social climate, but a reality we haven’t left far behind. A female director in Italy is still a rare thing. Production companies still invest very little in projects that bear the signature of the fairer sex, and female-directed documentaries are more likely to be financed than fiction films–the respected core of the cinema industry. The whole thing seems so anachronistic, especially when we take into account the fact that Italy’s first female director was making films before Luchino Visconti was even born…

Her birth name is Maria Elvira Giuseppa Coda. She never likes that Maria: to everyone, she is always just Elvira. She was born in 1875 in Salerno, and throughout her life, she will have an artistic and social vision moved by strong feminist ideals, according to which a woman, before a wife and mother, is an individual with passions, desires and professional ambitions to fulfill and satisfy just like a man. Her views lead her to be completely at odds with the female condition in late 19th-century Italy, which expects her to stay at home and take care of the family. Elvira, instead, looks to cinema, which is more than an infatuation: it is a true vocation. The Lumière Brothers, the inventors of the cinematograph, have initiated a magic of which the young woman is thunderstruck from her first viewing; before that white canvas, her eyes are enraptured by those strange moving images.

The third-born daughter of a cloth merchant of Cavese origin, Elvira’s life changes when her father, hoping to find more work, decides to move with the family to Naples. All the members of the Coda household support the family business, and amidst fabrics and sewing machines, Elvira lives the Naples of the early 20th century–a city in total turmoil, enlivened by the can-can rhythm of the Salone Margherita, in the shadow of Vesuvius from which hovers a timid plume. From the neighboring countryside, whole households flock to the city during this time, seeking employment opportunities and a better future; new neighborhoods are built while the old ones remain animated by the misery of poverty. Those who live in the belly of Naples are abandoned to a fate that seems already written: Roman politics is totally disinterested in the state of Campania’s capital, Elvira is not. In fact, these poverty-stricken people will be the very protagonists of her films.

Her love meeting with Nicola Notari, a former painter and photographer specializing in aniline coloring of photographic film, is crucial. Both have a strong attraction to the cinematograph, which they believe is the medium of the future. In 1902, Elvira becomes pregnant with their eldest son Eduardo, and so they marry; for the first years of their marriage, they make do financially with Nicola’s coloring business, but shift to celluloid film. In 1906, they finally realized the first step of their dream and founded “Dora Film” together, a production company named after their second daughter. The couple begins with the production of “arrivederci”, shorts that are shown at the end of films, in which the main characters are often played by their son Eduardo (he’s one of the first professional child actors of Italy and will later become a successful actor, starring in his mother’s films under the name Gennariello). But Elvira wants to cover deeper topics. She feels the need to tell the stories of the many Neapolitans who live like her in the Stella neighborhood–stories of femicides, guappi, divided families, illegitimate pregnancies, often hidden in the shadows of those dark alleys where the sun never shines. Drawing from the romanzi d’appendice (short novels that came out with the newspapers), theater, verses of Salvatore Di Giacomo and Libero Bovio, but also from crime news, Elvira creates, from 1916 to 1930, a vast production of about 60 feature films and a hundred short films and documentaries.

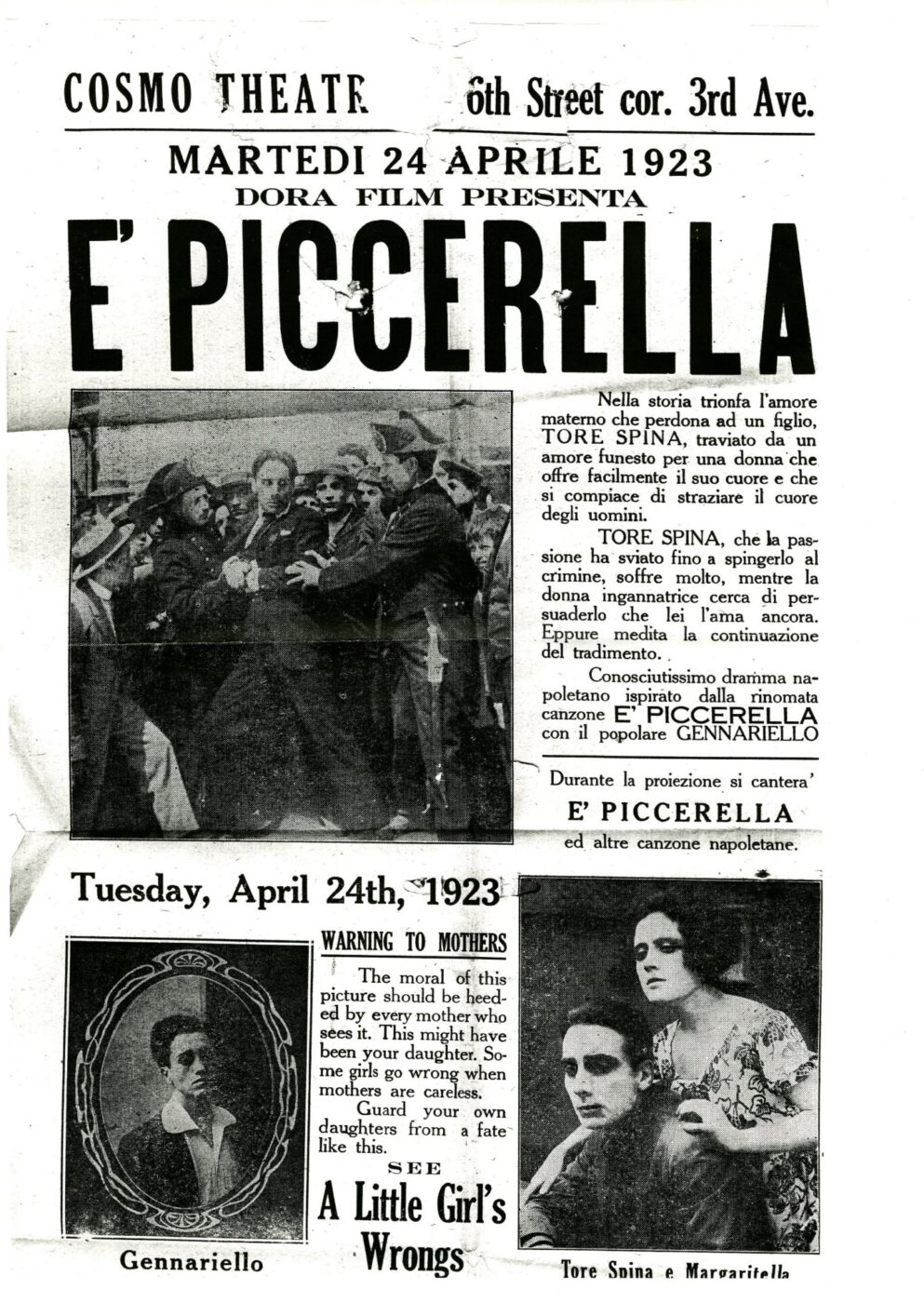

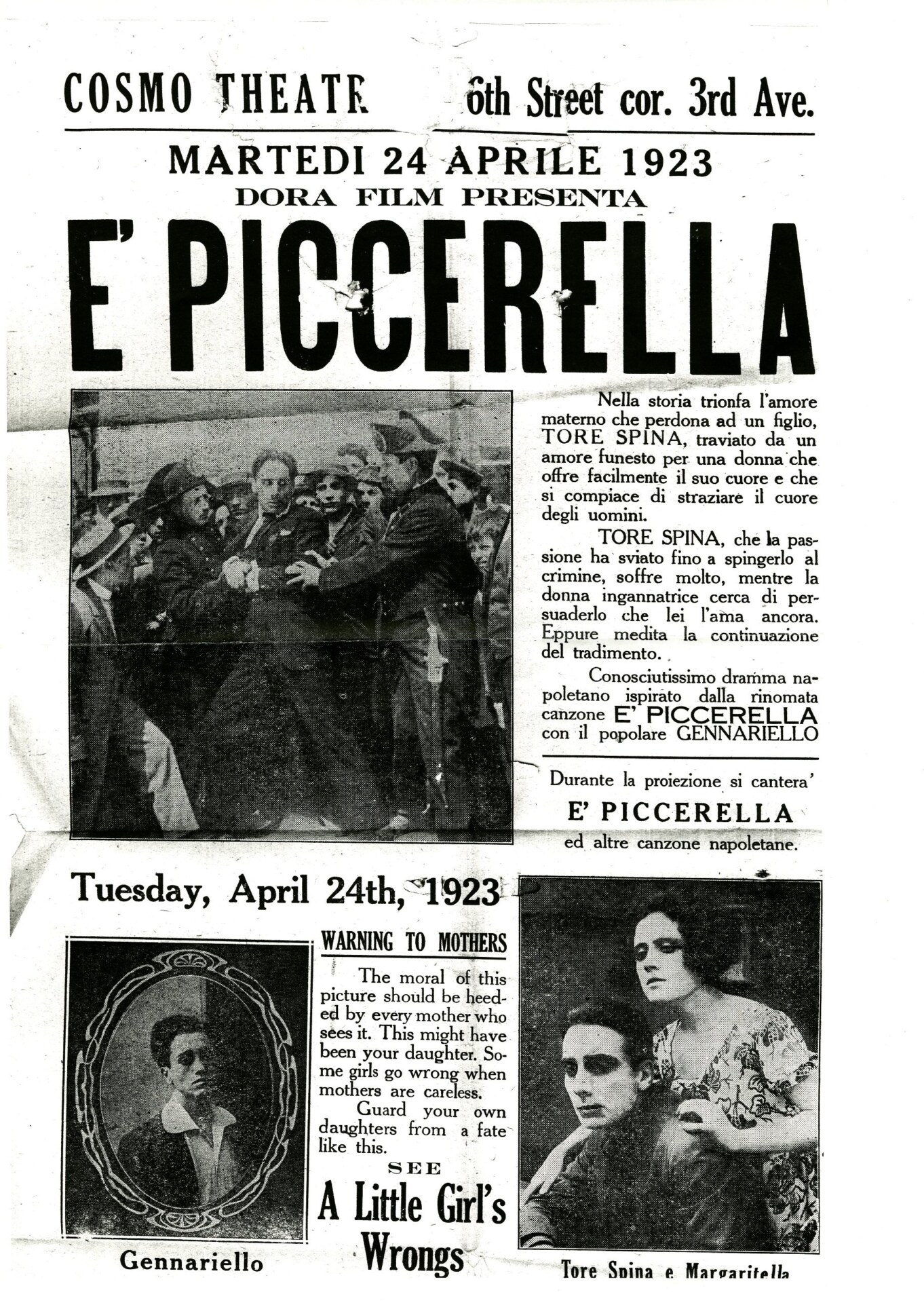

Carmela la Sartina di Montesanto (1916), ‘A legge (1920), ‘A Santanotte (1922), È piccerella (1922), Carcere (1923) and Fantasia e’ surdate (1927) are just a few of the titles that are one success after another in Naples and abroad, especially within the Italian-American communities in the states, where the Notari couple opens a branch in New York between 1920 and 1921. The films feature complex female protagonists: in ‘A Santanotte, Nanninella has two lovers, but marries the one she likes less to save him from murder charges; in È piccerella, Margaretella is cheating on Tore, who realizes that he’s squandered his family’s savings on expensive gifts for the young maid.

È Piccerella poster, 1923

Elvira leaves nothing to chance: in addition to writing and directing her films, she pays attention to press promotion and playbills, organizes the set, and above all, cares a great deal about the actors and their training. She makes actors repeat scenes over and over again until they reach perfection, because the slightest of expressions is fundamental in silent cinema. Elvira wants the drama, the love and the hurt to feel real. Audiences recognize this and fill the theaters to see her films.

Within the fascist regime, which favors “colossals” (think Lo squadrone bianco and Scipione l’Africano) and bourgeois, carefree, consumerist films (e.g. the films of director Mario Camerini) that venerate the Italian race and the prowess of the Roman Empire, Elvira paves the way for cinematic Neorealism. “A’ marescialla” (literally “female marshal”, as she is called by her family members because of her stubbornness and unwillingness to compromise), Elvira does not care what they think in Rome, nor in the salons of Naples’s upper echelons, where even Matilde Serao–one of Italy’s first female editors and co-founder of newspaper Il Mattino–does not appreciate her cinema.

The Duce’s propaganda machine admits no exceptions. With regard to the Neapolitan director, it is not just a question of like or dislike: cinema has proven to be a fundamental weapon, and no one (except perhaps Luchino Visconti) is allowed to make films outside of the regime’s authorized productions. So in 1928, the Censorship Commission sends a notice to Dora Film, putting an end to their activity with this statement: “Such films based on postmen, beggars, scugnizzi, dirty alleys, rags and people devoted to doing sweet nothing are a slander to a population that is working and trying to elevate itself in the tone of social and material life that the regime imposes on the country; considering, moreover, that such films are executed with criteria devoid of any artistic sense, unworthy of the beauty that nature has lavished on the land of Naples, it has been decided to deny in principle the approval of films that persist on circumstances that offend the dignity of Naples and the entire region.”

Dora Film closes its doors in 1930, and Elvira, defeated by a reality even more stark and violent then that recounted in her films, leaves Naples and retires with Nicola in Cava de’ Tirreni. There, she died on June 17th, 1946.

Most don’t know of her story. The operation of Fascist politics to cover up and overshadow her figure–by physically removing her films from theaters and archives–was alas a success. Almost nothing remains of her repertoire, except the feature films A santanotte (1922) and È piccerella (1922); a fragment of L’Italia s’è desta (1927); the short film Fantasia ‘e surdate (1927); and reels from the Festa della S.S. Assunta in Avellino and the Festa della Madonna della Libera a Trevico (1923)–all of which are preserved at the Cineteca Nazionale. For years, even film critics did not give her due credit, mistakenly pointing to Lina Wertmüller as Italy’s first female director. Only in the last decade has her story been reconstructed piece by piece, thanks to such painstaking works as the book Elvira Coda Notari. Metellian Traces of a Pioneer in Cinema by Patrizia Reso, but few exhibitions or events have been dedicated to her, and there is still much to be told to make her story known.

For those who want to learn more, I recommend Elvira, a novel written by journalist Flavia Amabile and published by Einaudi in 2022. Amabile shines light on her works, but also her character and her hunger for affirmation and self-love. What emerges is an authentic portrait of a woman who was a real revolution. A revolution that we still need today.

A century later, we still haven’t broken free from cinematic machismo, which, in reality, can be traced beyond the camera and the studio to a culture that struggles to conceive of women in roles of responsibility and power. According to data released by Cinecittà, female directors are behind only 13% of the total films produced in Italy from 2019 to 2020. Compared to the 2% in 2010, this is a leap forward, but we must not settle for small crumbs; there is a need for the political and financial structures of the cinematic world to change, but let’s also encourage female directors to network, unearth new talent and raise their heads just like Elvira did.