Giovanni “Gio” Ponti (1891-1979)

The first on this list for very good reason: Gio Ponti, one of the most famous and influential designers of the peninsula, is widely considered to be the father of 20th-century Italian modernism. With an unmistakable minimalistic and neoclassical “Novecento Italiano” signature, Gio Ponti’s design philosophy is more or less summed up by–his words–“Enchantment–a useless thing, but as indispensable as bread.”

After graduating from Politecnico di Milano with a degree in Architecture in 1921, Ponti went on to have a six-decade-long career as an architect and furniture designer. In the 1920s, as artistic director for the Tuscan porcelain maker Richard Ginori, he harmoniously fused the old with the new with contemporary ceramic forms decorated with motifs from Roman antiquity. In 1928, Ponti founded Domus–an innovative and influential leading art, design and architecture magazine still being published today. Named after the Latin for “home”, Domus was his (successful) attempt to make the decorative arts more accessible. Through the ‘40s and ‘50s, Ponti designed groundbreaking furniture pieces with a focus on function, elegance and aesthetics: to name just a few, the Sedia di Poco Sedile, Armchair 811, Mariposa, Continuum Rattan Armchair and D5551 Side Table. The latter is particularly key to understanding Ponti’s poetics in both design and architecture. The grid supporting the glass reflects the small, refined rosewood tables that Ponti had been designing since the 1930s, through which the framework of the table is part of the object’s aesthetics.

Ponti’s legacy still shapes the way we see the world around us: although never a self-declared “modernist”, Ponti is responsible for pushing Italian design forward at a never-before-seen pace. His work is now showcased across the globe, including the Molteni Museum in Milan.

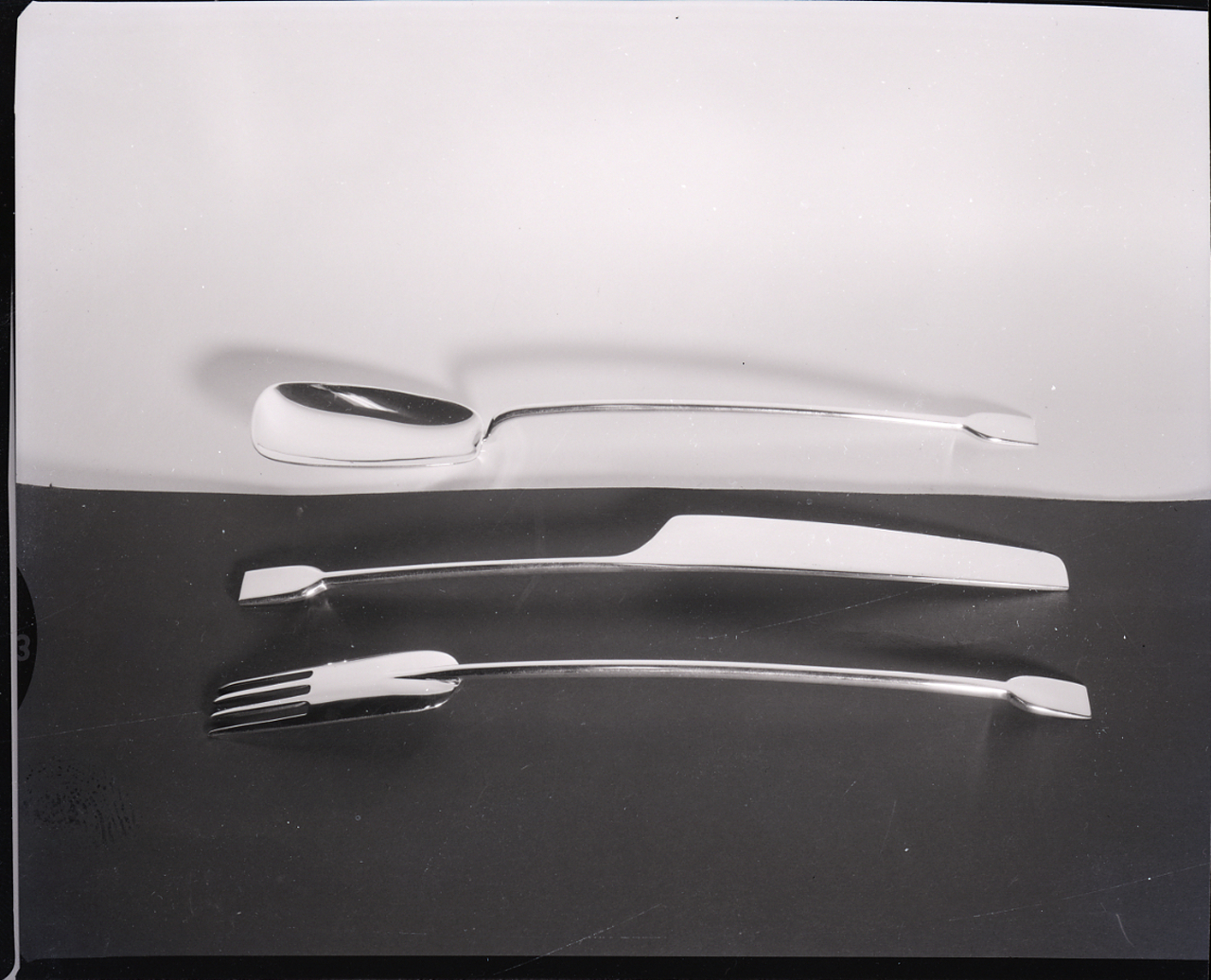

Cutlery designed by Gio Ponti; Photo by Paolo Monti - Available in the BEIC digital library and uploaded in partnership with BEIC Foundation.The image comes from the Fondo Paolo Monti, owned by BEIC and located in the Civico Archivio Fotografico of Milan., CC BY-SA 4.0.

Parco dei Principi in Sorrento designed by Gio Ponti

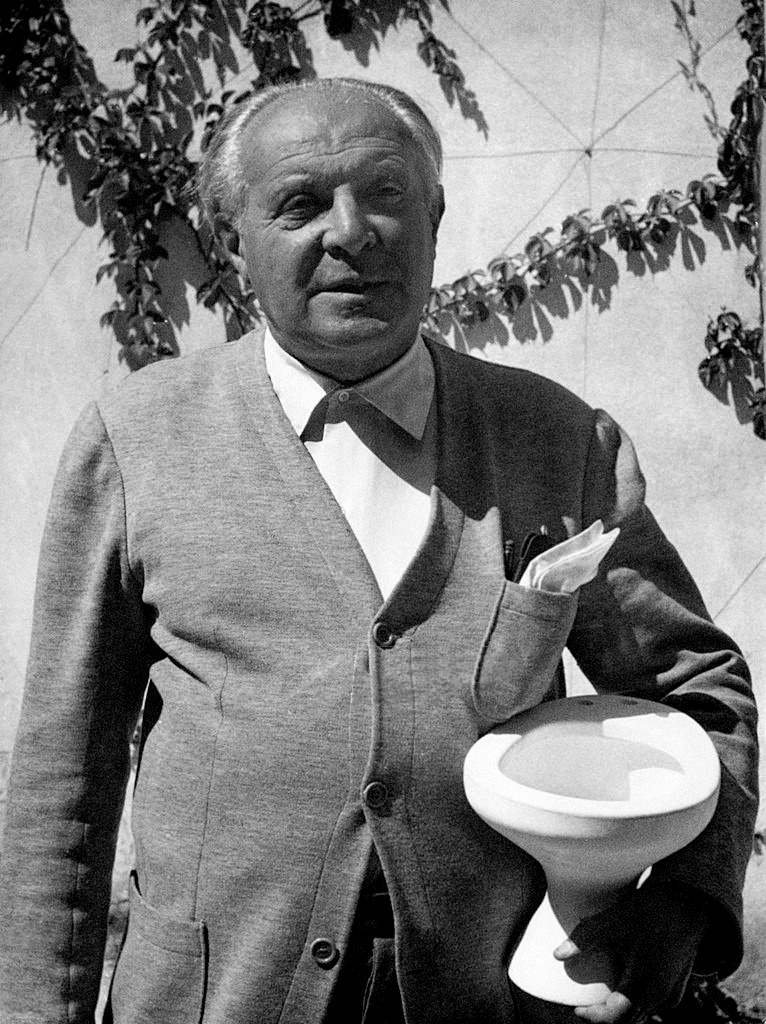

Gio Ponti

Carlo Mollino (1905-1973)

Carlo Mollino is remembered as much for his art and designs as for his fondness for cars, airplanes, and winter sports—influences that are easily seen in his works. In the sinuous curves of the wooden frames that support his tables, one may retrace snow-covered slopes for skiing and tracks where he used to drive his fast cars. The metal joints connecting many of his design pieces recall aviation engineering and his alpine architectures show frames rising up into the sky.

After studying Architecture at Politecnico di Torino in 1931, Mollino worked with his father who ran an engineering company, but by the 1940s, he was creating his own one-of-a-kind designs for chairs, tables, and even automobiles. (In 1955, he co-designed the Bisiluro da Corsa, a sleek, experimental race car with twin hulls for the 24 Hours of Le Mans.) One of his most recognizable designs is the Fenis chair (1959)—sculpted from solid maple wood and characterized by its folk-inspired backrest of two carved vertical slats. Another signature work is the Cavour Desk (1949), designed for his Turin office: a daring mix of glass, floating drawers, and a swooping wooden leg that channels both propeller blades and alpine slopes. Forever in search of lightness and dynamism, Mollino was one of the few architects to introduce elements of Surrealist art and culture into the Modern Movement: “Only when a work is not explainable other than in terms of itself can we say that we are in the presence of art,” he once said.

Today, you can visit Museo Casa Mollino in Turin, the designer’s most enigmatic project. Conceived in the 1960s—not as a residence, but as a kind of metaphysical retreat—Casa Mollino was never meant to be lived in. Overlooking the River Po, the apartment was a private, symbolic work filled with layers of esoteric references: velvet-draped rooms, gold-leafed nudes, erotic photography, and a precise blend of Baroque opulence and modernist control. Everything down to the textiles and tableware was selected by Mollino himself. Uninhabited during his lifetime and only revealed to the public decades after his death, the space reads like a three-dimensional autobiography and can be visited by tour only.

Museo Casa Mollino in Turin

Museo Casa Mollino in Turin

Franco Albini (1905-1977)

Few designers could make rattan feel architectural or turn a bookshelf into a feat of engineering. Franco Albini did both—applying Rationalist principles to humble materials in projects from armchairs to metro stations.

After studying architecture at Politecnico di Milano, Albini trained under Gio Ponti and soon emerged as a central figure in the Rationalist movement before WWII. He was drawn to traditional Italian techniques but approached them with a modernist’s eye—experimenting with affordability, lightness, and modularity. His early experiments with bent cane and rattan led to the Margherita (1950) and Gala chairs, produced by Bonacina: airy forms that looked like sculpture but were made for everyday use.

But his most iconic piece is the Luisa chair (1955), which took 15 years to design. With its sharp lines, exposed joints, and spare silhouette, Luisa distilled Albini’s philosophy of “maximum effect with minimum material.” It earned him the Compasso d’Oro. Just as structurally daring was the Veliero bookshelf (1940), a suspended system of tension cables and glass shelves that seems to float mid-air.

Albini’s talents extended beyond furniture. With longtime collaborator Franca Helg, he designed everything from department stores (including Rinascente in Rome) to offices (INA in Parma), and reimagined Milan’s Line 1 metro stations with rational layouts, clear wayfinding, and modular detailing that still define the city’s underground aesthetic.

Today, many of Albini’s works remain in production through Cassina and Bonacina, and his legacy is preserved at the Fondazione Franco Albini in Milan.

Milan metro designed by Franco Albini

Rome, the Rinascente staircase by Franco Albini; Photo by By Paolo Monti - Available in the BEIC digital library and uploaded in partnership with BEIC Foundation.The image comes from the Fondo Paolo Monti, owned by BEIC and located in the Civico Archivio Fotografico of Milan., CC BY-SA 4.0

The Rinascente in Rome, Photo by Federico Di Iorio - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Osvaldo Borsani (1911-1985)

Osvaldo Borsani approached design as both engineer and aesthete, merging the artisanal traditions of his upbringing with the demands of a rapidly modernizing world. Born in Varedo to a family of cabinetmakers, he began apprenticing under his father Gaetano Borsani at Atelier di Varedo as a teenager. This early training in finely crafted, deco-inflected furniture laid the groundwork for his later pivot toward modernism.

After earning his architecture degree at Politecnico di Milano, Borsani made his mark at the 1933 Milan Triennale with Casa Minima—a compact prototype house that combined modular systems and pared-down geometry with an innovative mix of materials: tubular steel, palm wood, white parchment, and tempered glass. It reflected the emerging Rationalist aesthetic and earned him the fair’s silver medal, but more importantly, it marked a break from ornamentalism and pointed toward a new, functionalist future.

That future took shape in 1953 when Borsani co-founded Tecno with his twin brother Fulgenzio. Their goal: to industrialize design without sacrificing elegance. At Tecno, Borsani introduced one of his most iconic pieces, the P40 chaise longue (1955)—a reclining lounge chair with a metal frame, adjustable backrest, flip-out leg support, and rubber-arm side wings. Described as “a machine for sitting,” it could be positioned in 486 different ways, marrying precision engineering with comfort. It remains one of the most adaptable lounge chairs ever produced.

Other standouts from Tecno’s early catalog include the D70 divan, with a split seat and back that pivot open like a book, and the Graphis office system (1968), a modular workspace concept that anticipated today’s flexible office environments. Today, Borsani’s work can be found in major collections including the Triennale Design Museum in Milan, the MoMA in New York, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Osvaldo Borsani for Tecno lounge chair at Triennale; Photo by Sailko - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Osvaldo Borsani pieces at Triennale, Photo by Ggerly - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Piero Fornasetti (1913-1988)

Piero Fornasetti was a visual polyglot—an artist who moved seamlessly between drawing, painting, printing, and design. After being expelled from Milan’s Brera Academy for insubordination, he opened his own art printshop in 1930, laying the foundation for what would become the singular Fornasetti universe. Collaborating with artists like Fabrizio Clerici and Alberto Savinio, he produced limited-edition books and lithographs before turning toward furniture and interiors.

A pivotal meeting with architect Gio Ponti in 1940 sparked a long-running collaboration and nudged Fornasetti toward design for daily life. With Ponti’s encouragement, he began crafting furniture, trays, ceramics, and screens—all canvases for his dreamlike illustrations. His world was filled with optical illusions and neoclassical whimsy: suns, moons, playing cards, and the endlessly reimagined face of opera singer Lina Cavalieri, whose image became a signature motif across more than 350 variations.

In 1956, he opened the first Fornasetti store on Milan’s Via Manzoni, where his pieces were often described as “practical madness.”

“I am my furniture and the pieces are my personal biography,” he once said. “What I did was something more than decoration—it was an invitation to the imagination.” Today, the Fornasetti Atelier continues under the direction of his son Barnaba, producing both archival reissues and new works that honor Piero’s legacy.

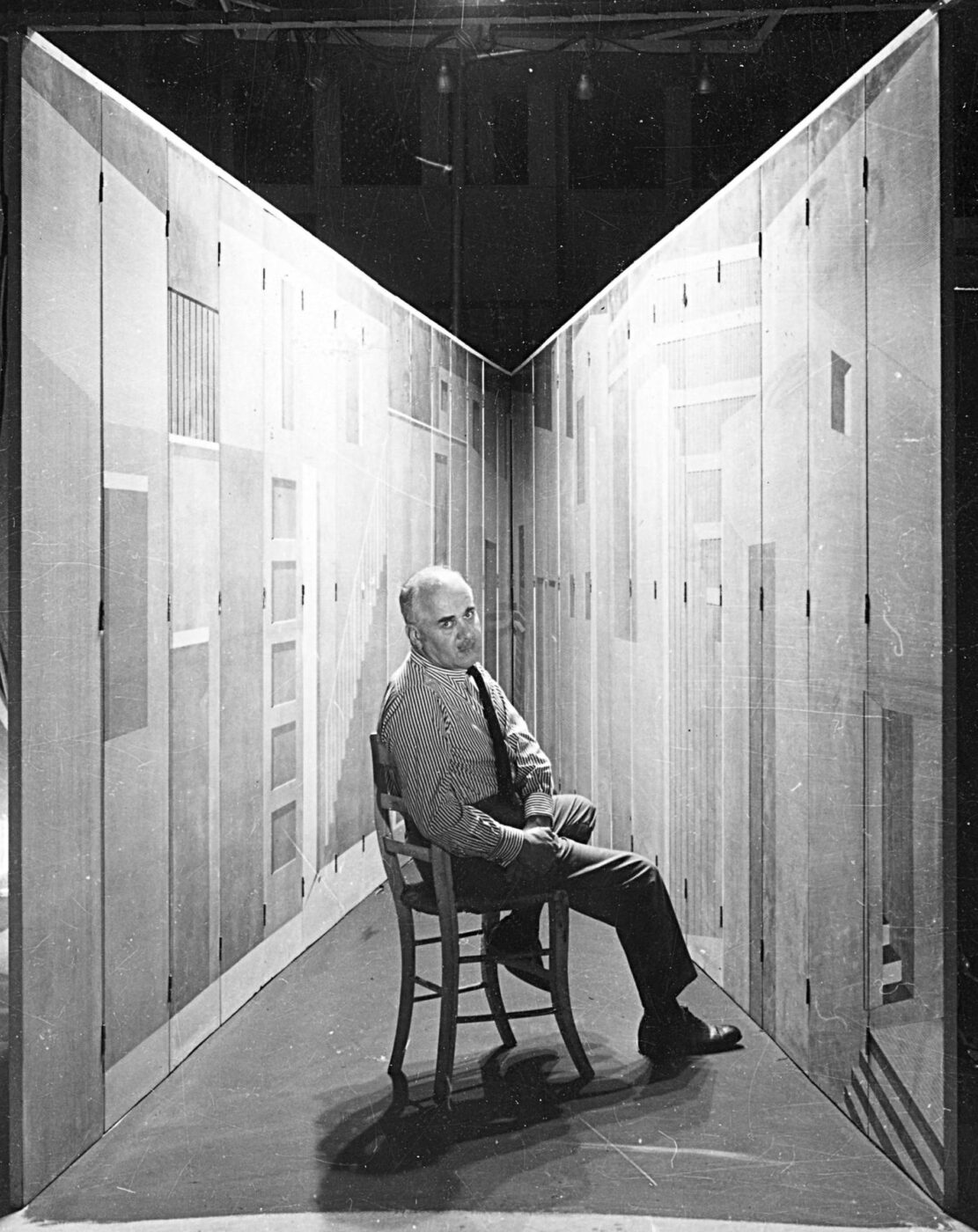

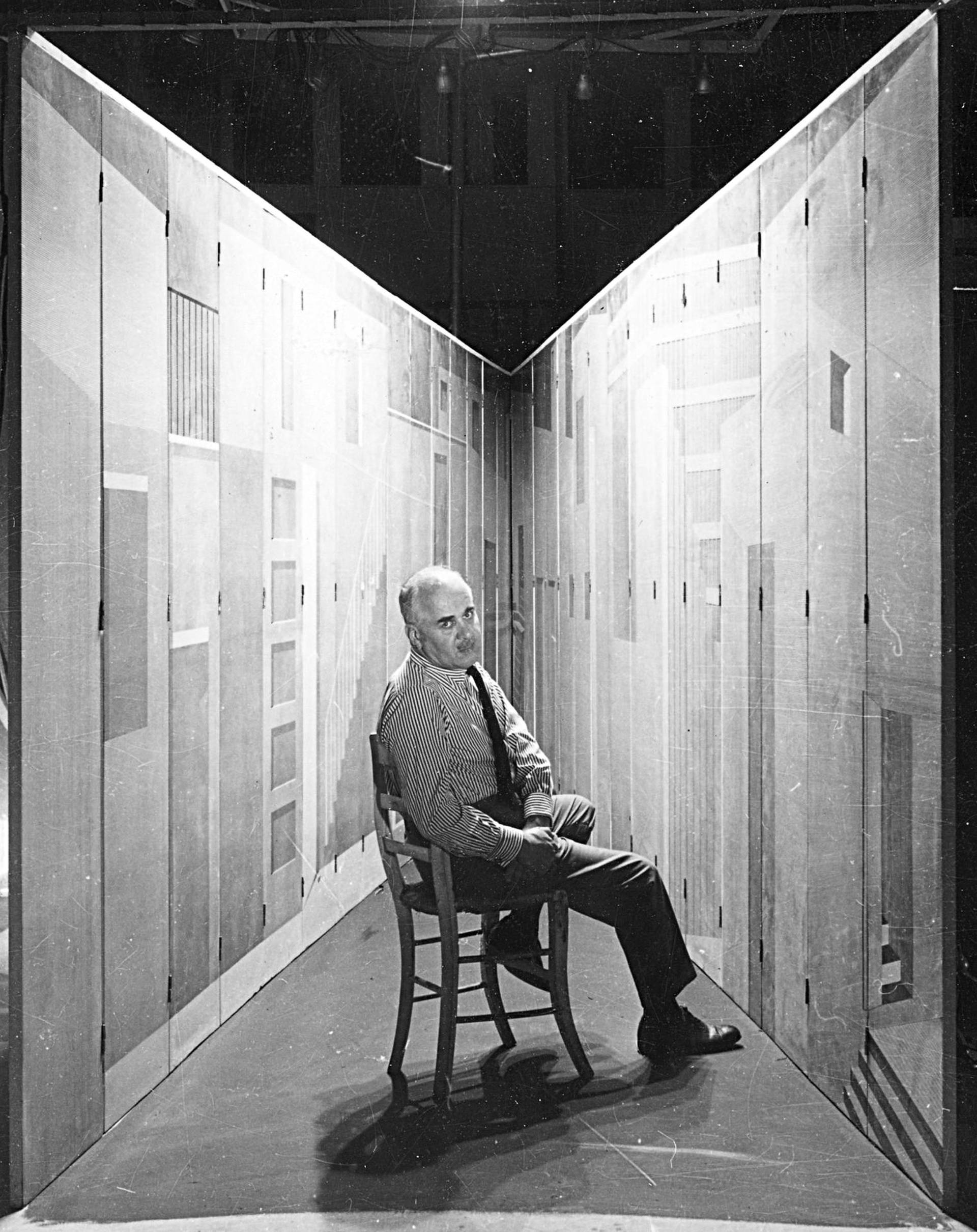

Italian artist Piero Fornasetti sitting in his La Stanza Metafisica

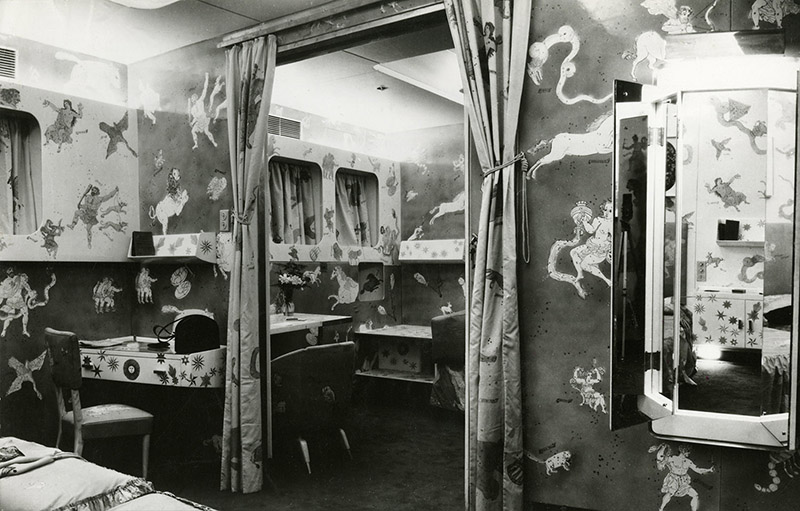

Interior of the Andrea Doria ocean liner; Photo by Fornasetti - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007)

Few designers shaped the visual language of late 20th-century design like Ettore Sottsass. Known for his irreverent style and radical vision, he helped explode the boundaries between high design, pop culture, and everyday life. After graduating in architecture from the Politecnico di Torino in 1939, he briefly relocated to New York in 1956 to work under George Nelson—an early brush with American modernism that would inform his global outlook.

Sottsass’s breakthrough came in 1958, when he was hired as a design consultant for Olivetti. There, he created everything from typewriters to mainframes, including the Valentina typewriter (1969), a bright-red, portable machine that won him the Compasso d’Oro. In the late ’60s and ’70s, he collaborated with experimental collectives like Superstudio and Archizoom, exploring anti-functionalism and radical aesthetics before founding his own Milan-based studio.

“When I was young, all we ever heard about was functionalism, functionalism, functionalism. It’s not enough. Design should also be sensual and exciting.” That ethos crystallized in 1981 when he founded the Memphis Group, a bold collective of designers who rejected minimalism in favor of big colors, asymmetry, and zany attitude. During this period, Sottsass designed his most iconic pieces: the totemic Carlton room divider, the zigzagging Casablanca cabinet, and the bird-like Tahiti lamp.

Today, the Memphis aesthetic is as polarizing as it is influential (it practically defined the look of the ‘80s and early ‘90s) but Sottsass’s belief that design could be fun remains deeply resonant.

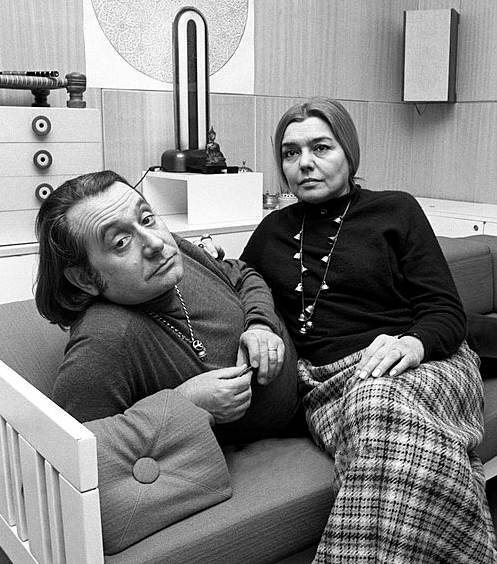

Italian architect and designer Ettore Sottsass sitting in his home with his wife Fernanda Pivano, an Italian writer and translator. Milan, March 1969.

Ettore Sottsass design pieces at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London

Achille Castiglioni (1918-2002)

Achille Castiglioni approached design with equal parts precision and play. A graduate of Politecnico di Milano, he joined his brothers Livio and Pier Giacomo in founding Studio Castiglioni, where they became known for turning everyday objects into clever, enduring designs—always rooted in utility, but never without a wink.

“Design shouldn’t be trendy. Good design should last over time, until it wears out,” he once said. That philosophy lives in his iconic pieces: the Arco lamp (1962), with a marble base and sweeping arc of stainless steel; the Sella stool (1957), topped with a bicycle seat; and the Mezzadro (1957), a tractor seat reimagined as a playful perch. Whether designing an ashtray, a beer dispenser, or a light fixture, Castiglioni infused each object with humor but not at the expense of human insight.

A founding member of Italy’s Association for Industrial Design in the 1950s, he spent six decades shaping how design could, and should, function in daily life. His work remains in production—through Flos, Zanotta, and Alessi—today.

Flos Lamp by Achille and Piergiacomo Castiglioni

Brothers Achille and Piergiacomo Castiglioni; Courtesy of Flos - https://flos.com/it/prodotti/lampade-tavolo/taccia/taccia/, CC BY-SA 4.0

Vico Magistretti (1920-2006)

Born into a prominent family of Milanese architects, Vico Magistretti developed a design language that was both experimental and refined—stripping forms down to their essence without ever losing warmth. During World War II, he escaped military deportation and fled to Switzerland, where he studied under humanist architect Ernesto Nathan Rogers, who would become a lifelong influence.

In the 1960s, Magistretti began collaborating with major Italian brands like Artemide, Oluce, and Cassina, producing a string of modern classics. His Eclisse lamp (1965), a playful yet functional design for Artemide, features a rotund metal body and a rotating inner shade that allows the user to “eclipse” the bulb, modulating the light—an idea that earned him the Compasso d’Oro in 1967. Other standouts include the stackable plastic Selene chair (1969) for Artemide and the sculptural Maralunga sofa (1973) for Cassina, a plush, deep-seated piece with adjustable headrests hidden inside each back cushion—activated by a gentle pull—to allow the sitter to shift between upright support and laid-back lounging.

Today, you can see his pieces on view at the likes of MoMA in New York and the Triennale Design Museum in Milan.

Milan, Photo by Paolo Monti - Available in the BEIC digital library and uploaded in partnership with BEIC Foundation.

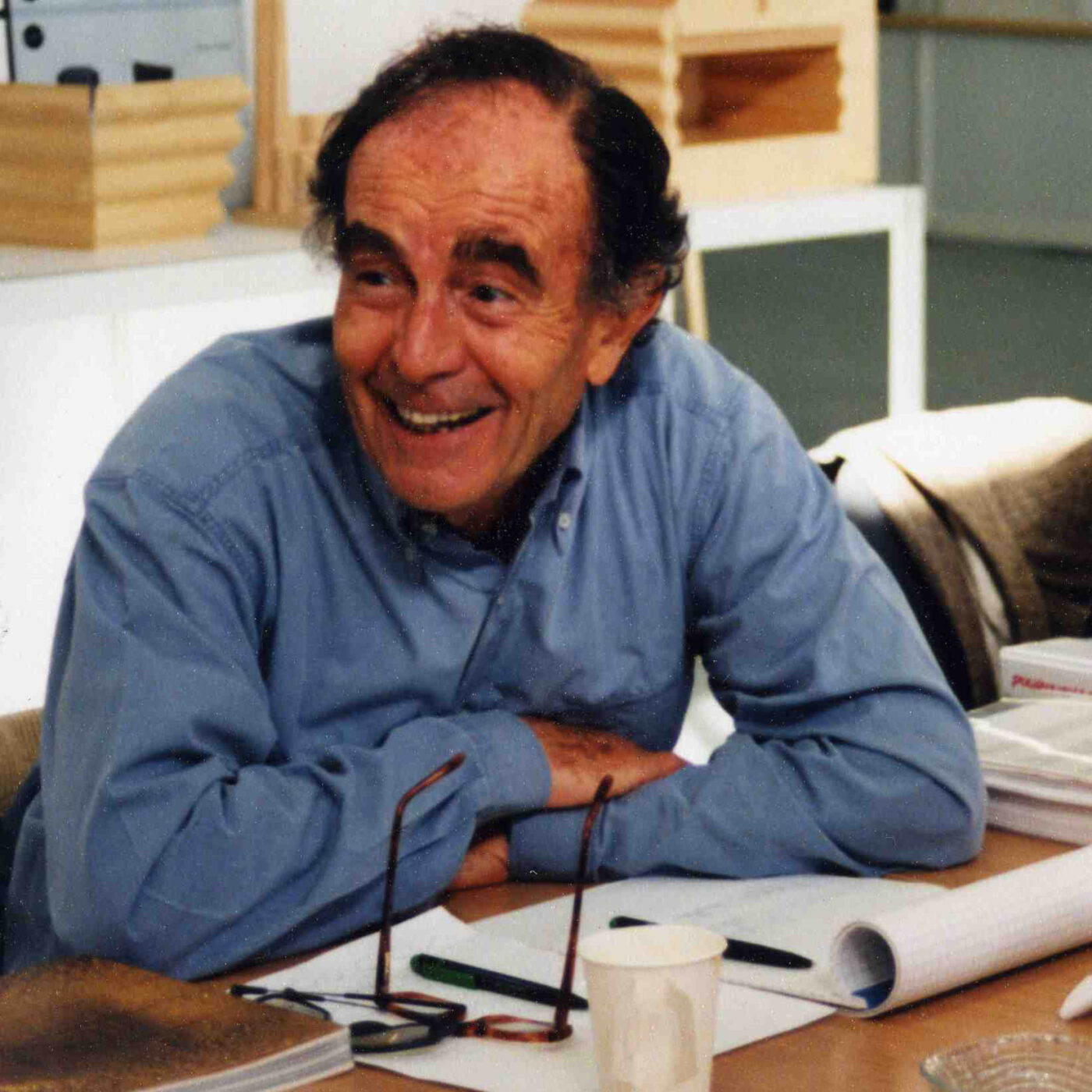

Vico Magistretti; Photo by Fondazione studio museo Vico Magistretti, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62370012

Gaetana “Gae” Aulenti (1927–2012)

A key figure in Italy’s post-war design scene, Gae Aulenti brought architectural clarity and character to everything from furniture to major public spaces. After graduating as one of just two women in her class at Politecnico di Milano, she joined Casabella magazine before turning to industrial design in the 1960s. Her best-known piece, the Pipistrello lamp for Olivetti, pairs a telescopic stem and “bat”-like shade with a soft, diffused glow.

“I aim to create furniture that appears in a room as buildings on a skyline,” Aulenti once said. She carried that ethos into her role as artistic director at FontanaArte from 1979 to 1996, where she helped usher the brand into a new modernist phase. Under her guidance, she designed enduring pieces like the Tavolo con Ruote (a glass table on industrial wheels), the Tour table (a spin on it with a bicycle wheel as base), and the Parola lamp, co-designed with Piero Castiglioni.

Though it’s her transformation of the Gare d’Orsay into the Musée d’Orsay that remains one of her most celebrated works—an adaptive reuse project that turned a Beaux-Arts train station into a world-class museum. In recent years, Exteta released a re-edition of her 1964 Locus Solus collection, originally created for Poltronova and a radical departure from the muted tones of the time: outdoor furniture made of bright, tubular steel frames in bold oranges and yellows, paired with graphic-printed cushions.

Italy Pavilion of Expo 1992; Photo by Jl FilpoC - Opera propria, CC BY-SA 4.0

Gae Aulenti

Gaetano Pesce (1939–2024)

No one made furniture feel more alive—or more subversive—than Gaetano Pesce. With resin as his medium and rebellion as his method, he bent architecture, product design, and art into wildly original forms that defied symmetry, tradition, and complacency.

Born in La Spezia in 1939, Pesce studied architecture at the University of Venice under Carlo Scarpa and Ernesto Rogers. In 1959, he co-founded Gruppo N, a collective focused on kinetic art and rooted in Bauhaus principles. By the 1960s, he emerged as a key figure in the Italian Radical Design movement, using unconventional materials and bold colors to push design into political and emotional territory.

His most iconic work—the UP5 “La Mamma” Chair (1969) for B&B Italia—is both playful and confrontational. Inspired by ancient fertility figures, the voluptuous chair came vacuum-packed and expanded on release, paired with a tethered ottoman evoking a ball and chain. It was a clear, unapologetic commentary on the systemic oppression of women. In later years, his Rosetta Modular Sofa (2021), inspired by the Milanese bread roll of the same name, offered flexible, puzzle-like seating.

Pesce extended this fearless experimentation into architecture: the plant-covered Organic Building in Osaka and the surreal Children’s House at Paris’s Parc de la Villette are prime examples, as is Il Pescetrullo in Puglia, which reimagined traditional trulli homes with dreamlike, biomorphic shapes.

“I strive to seek new material that fits into the logic of construction while performing services appropriate to real needs,” he once said—a philosophy that shaped not only his objects, but his lifelong approach to teaching at Domus Academy, Cooper Union, and beyond. His work lives on in the permanent collections of MoMA, the V&A, and the Centre Pompidou.

Gaetano Pesce's Organic Building (1993) in Osaka, Japan. The walls of the construction feature extruded pockets with plants, thus creating an impromptu vertical garden. Photo by Hiromitsu Morimoto - Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0

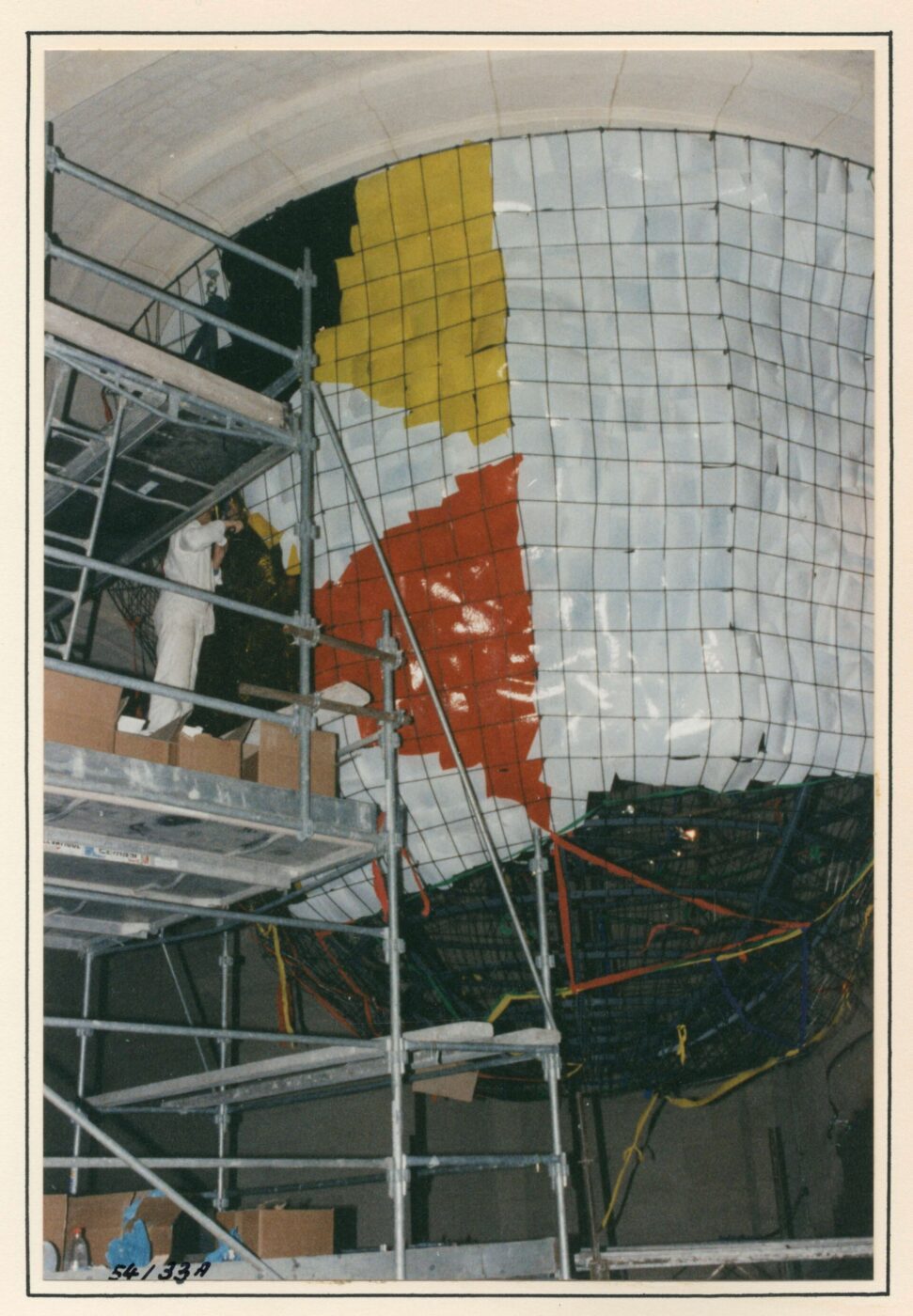

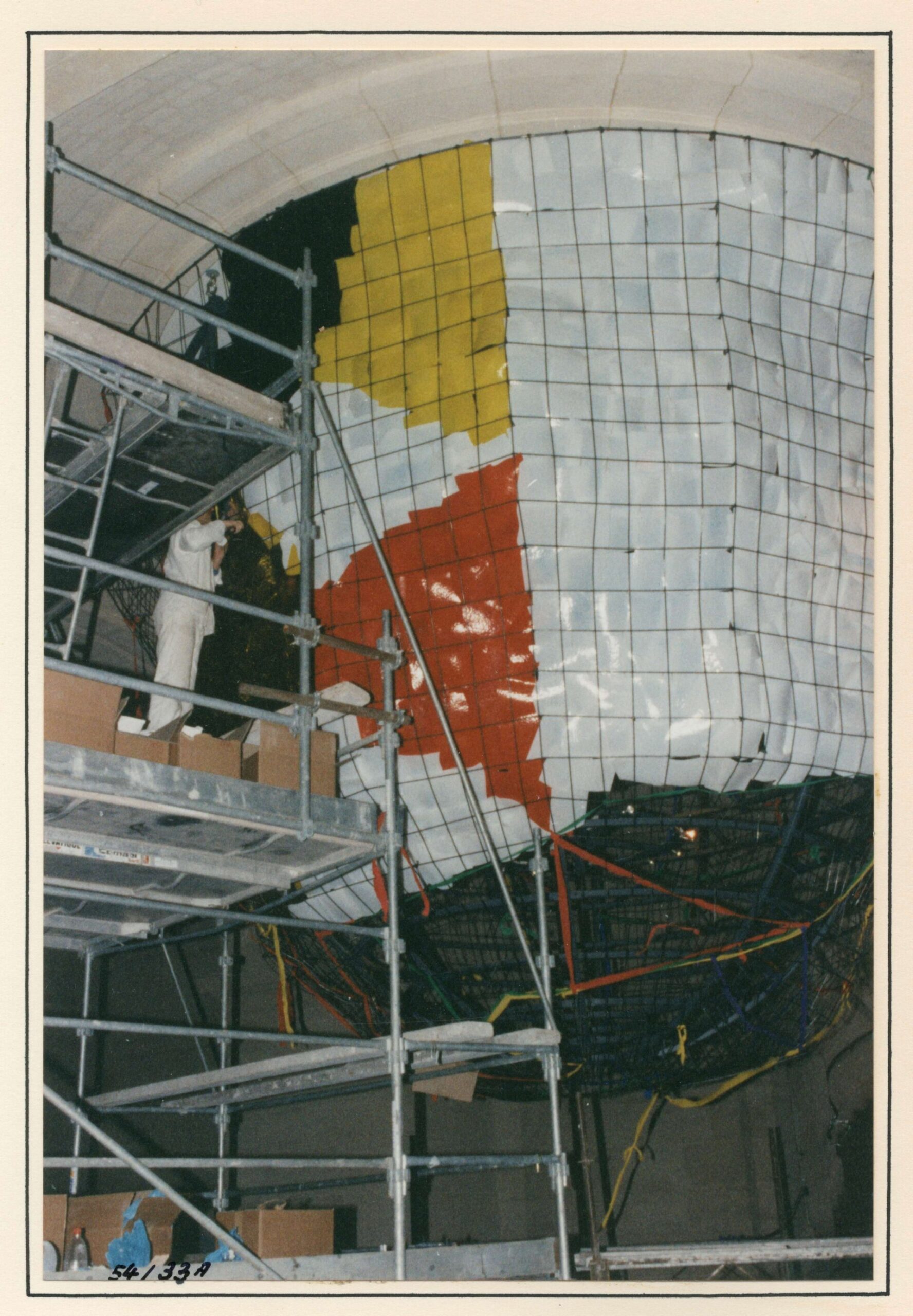

Weitere Einzelheiten Installation of the chandeliers in the museum in 1997. It was ordered to the Italian artist Gaetano Pesce for the entry; Photo by Von PBA Lille - Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 4.0