According to a series of global surveys both silly and serious, Italian food is the most popular in the world. The country has long been revered for its vast and regionally rich cuisine, boasting the ubiquitous favorites of pizza, pasta, gelato, and, wow, does the list go on. There are countless wonderful things to see and do in this country, but let’s be honest: when tourists visit Italy, they visit for the food.

Given such mania for Italian cuisine, it’s unsurprising that Italian restaurants have popped up in all four corners of the world, and that the aisles of most international supermarkets are stocked with well-known Italian ingredients; parmesan, mozzarella, and the like. The idea is simple. These products and restaurants offer consumers access to Italy’s famed food tradition. Given the context of globalization, this seems like a fairly innocent concept at first glance. And yet, things start to get murky when the question arises: do all of these Italian restaurants and products have a legitimate connection to Italy’s food industry, or are they just profiting off of the international reputation of Italian cuisine? It is precisely this potential for disconnect between the “Italian” food industry abroad, and Italy itself, that has brought on the so-called “Italian Sounding” dilemma.

“Italian Sounding” refers to a marketing technique in which the Italian “image” is used to sell or promote food products and brands that, in reality, have nothing to do with Italy. This might look like the use of the Italian flag, Italian words, or Italian “pictures” (such as the leaning tower of Pisa) on food packaging or restaurant menus. By presenting food in a way that makes it seem Italian, consumers are essentially deceived into thinking that what they are purchasing is a genuine Italian product, or has in some way an authentic link to Italy’s food tradition. By pretending to be Italian, these businesses are able to profit off of the popularity and reputation of Italian food, without investing the money needed to actually import food products from Italy. To put it simply, the Italian Sounding phenomenon is one, huge scam.

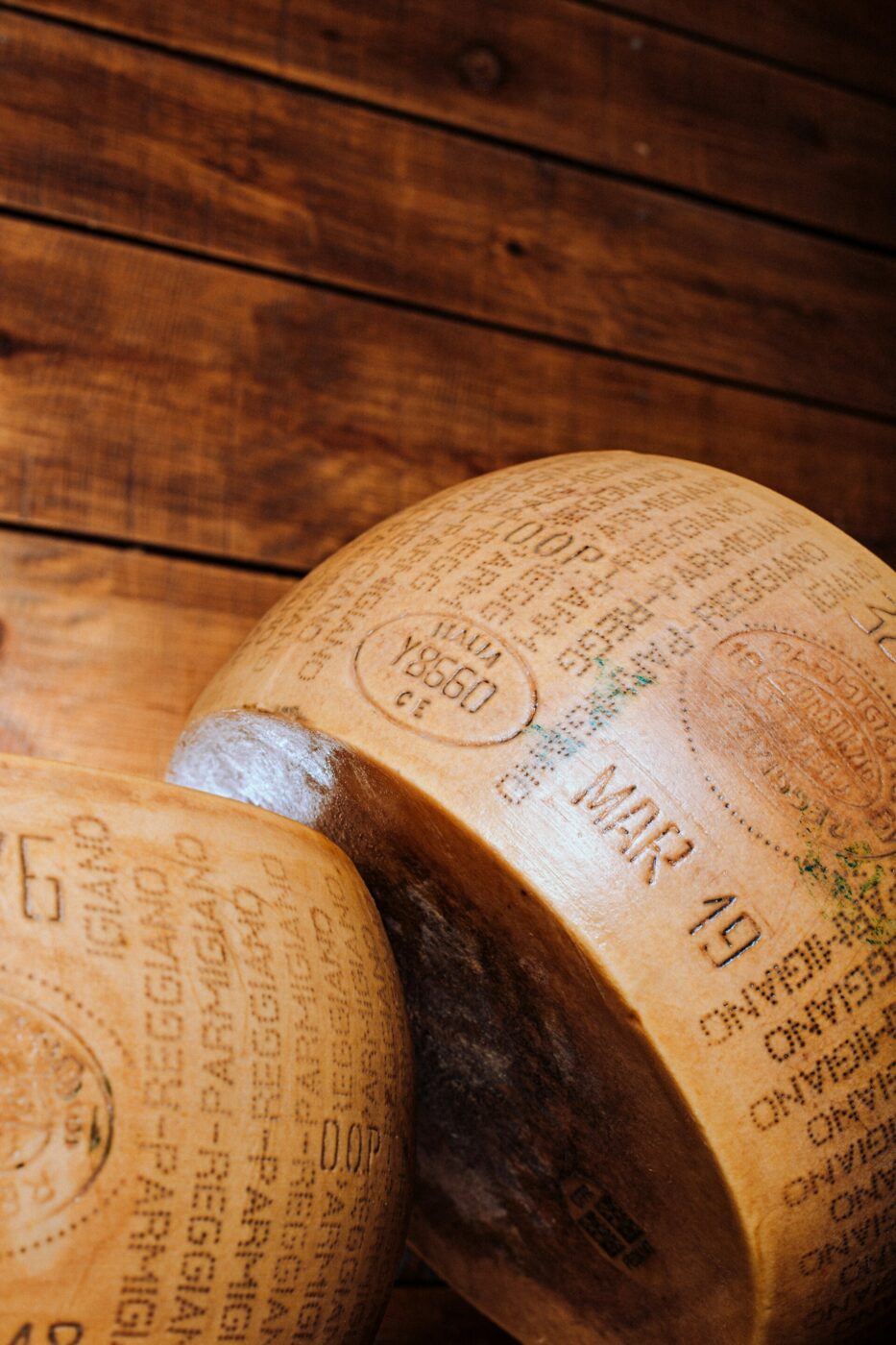

Parmesan cheese is not the same as Parmigiano

Despite its contemporary trashiness, Italian Sounding actually has rather romantic roots in 19th-century Italian diasporas. Wanting to produce Italian food without the means to import products from Italy, emigrants added the “local” touch with Italian names and images. This disconnect from the real “Made in Italy” was not limited to raw products. Over time, recipes became more and more detached from the Italian originals, evolving alongside the diaspora itself–examples being fettuccine Alfredo or spaghetti with meatballs.

The original connection with Italian emigrants is apparent in the phenomenon’s particular prevalence in North and South America, both home to historic Italian diasporas. Now, however, Italian Sounding has spread far beyond the homesick creations of first generation Italians, and has transformed into a major money making scheme, allowing massive international corporations to sell the “Italian food experience” outside of Italy.

To say it’s harming Italy’s food industry is an understatement. Two out of three “Italian” agri-food products are not made in Italy; that means that genuine Italian food products are being neglected in favor of the fake Italian products, which typically retail for lower prices. The Italian Sounding market makes an average of 66 billion dollars a year, a staggering sum spent on counterfeit food items. The hugely lucrative industry involves major international players, with most of the fraudulent products manufactured by businesses in wealthy countries such as America and Australia, and whose investments in marketing and production dwarf the efforts of independent Italian food companies.

Example of fake "Mozzarella di bufala"; Photo by Milka Crem, Philippine Carabao Center

Not only is Italian Sounding financially damaging, but it also negatively impacts the way Italian food is perceived abroad. Those pulled in by the convincing packaging and attractive price tag are disappointed by food products that inevitably fail to match up to the Italian original. Given how successful this empire is, it’s unsurprising that the examples of fraudulent products are vast. The top most counterfeited Italian product globally is Parmigiano Reggiano, often replaced by “parmesan” (unless it’s officially labeled as “Parmigiano Reggiano”, it’s not the real thing). This cheese, along with its sister Grana Padano, has more counterfeit versions being sold worldwide than originals. Second place goes to the infamous mozzarella di bufala, and in third place comes prosecco. Brands typically replicate names or use adjacent terms to sell products that ultimately have very little to do with the traditional production methods so fiercely protected in Italy. Slap a tricolor flag on a packet of a white ball of cheese, and most international customers will assume it’s Italian mozzarella. Browse a local supermarket outside of Italy, and, odds are, the pesto is from Pennsylvania, the robiola from Canada, and the parmesan from Brazil.

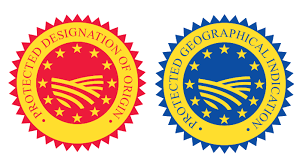

PGI (Protected Geographical Indication); PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) stamp; look for these to ensure the authenticity of your products

Efforts have been made to combat the issue, which is quite literally stealing food from the mouths of Italian producers. Neapolitan app “Authentico” aims to stamp down on the consumption of fake Italian products with a bar-code scanning system, letting shoppers quickly check whether supermarket items are the real deal before they buy. If it flashes up as a counterfeit product, the app gives you the option to report it, encouraging individual consumers not only to avoid buying Italian Sounding food and wine, but also to actively fight the burgeoning trend. The Italian Trade Agency and Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs launched a series of collaborative efforts to combat fraudulent food products being sold abroad, while the Ministry for Business and Made in Italy is wholly dedicated to fighting counterfeiting and protecting Made in Italy products on both a national and international scale. Rather than only working to export the biggest and most lucrative brands out of the peninsula, the Made in Italy label provides an important stamp of certification to smaller, independent producers, allowing them to compete with global names and thus ensuring they continue to play a key role in the country’s economy.

The official Made in Italy label

As for what can be done on an individual level, you can check food packaging for official EU stamps such as the PDO (Protected Designation of Origin), which certifies the product was produced in a specific area in the traditional way; PGI (Protected Geographical Indication), used for products whose quality is based on geographical area of production; and DOC (Controlled Designation of Origin), which specifies wines are produced in compliance to strict regulations. Without active effort, real Italian food products are in danger of losing out to Italian Sounding counterfeit ones, which are already making a staggering three times the annual revenue of Italian exports, a worrying figure that highlights the very real risk at play. Learning about and appreciating Italy’s rich culinary heritage extends far beyond an individual interest, but in this case, becomes an act of communal solidarity, ensuring that the country’s agri-food producers can continue to produce the food products that Italy is famed for; the ones that the world wanted to replicate in the first place.