“Gondola, Gondola!” The familiar call rings through Venice’s tight waterways, hawked at passersby from figures donning red- or blue-striped shirts and straw hats. These gondoliers, and their sleek, seductive boats, have become icons (to say the least) of La Serenissima. But what does it take to perfect the art of passing another boat with barely a centimeter to spare?

A lot. Only 440 gondoliers remain in Venice today—a fraction of the 10,000 who once crowded the city’s waterways. Each gondolier buys, maintains, and personalizes their own boat, mastering a craft that takes years of training, skill, and intimate knowledge of Venice itself.

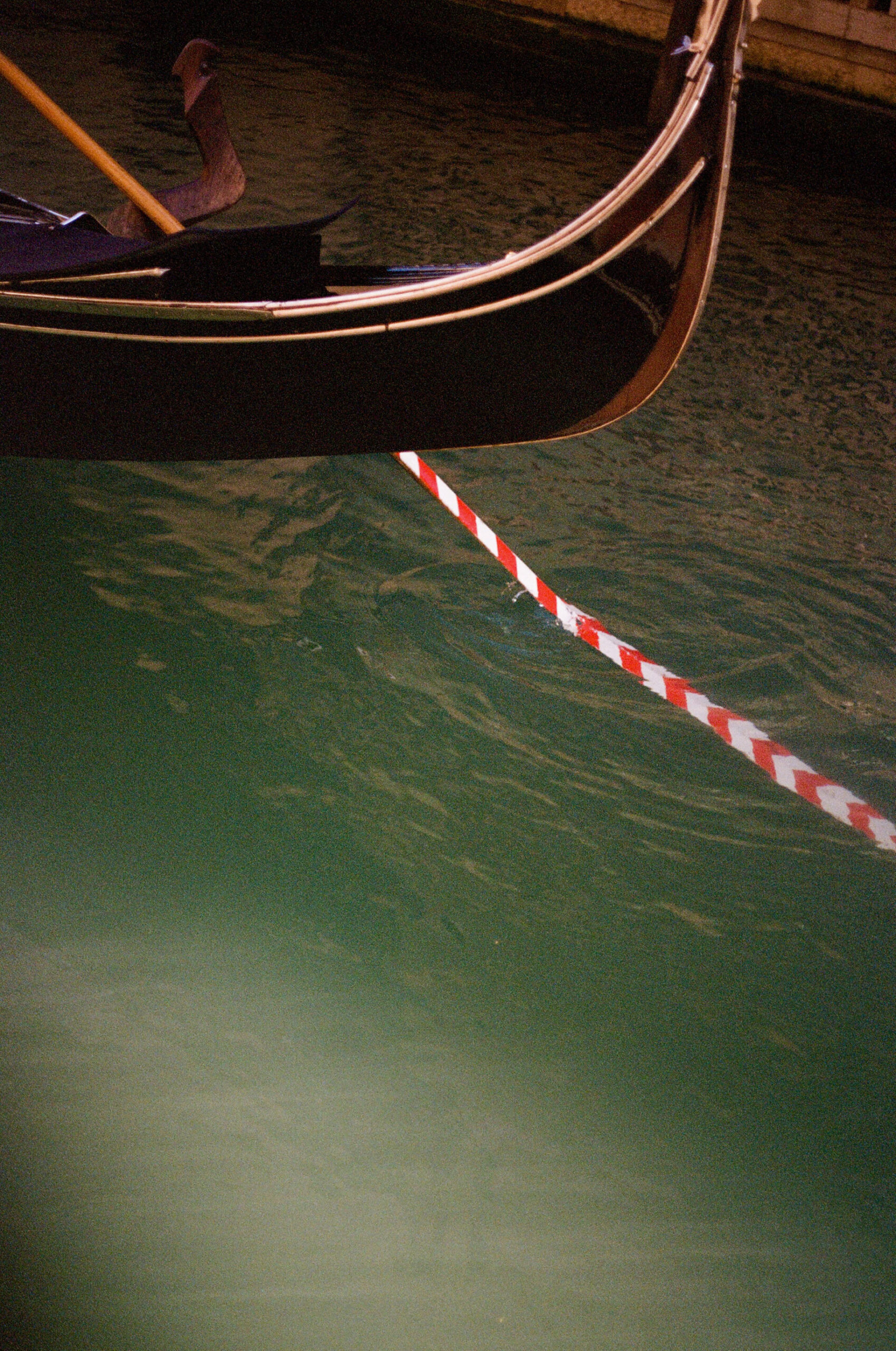

Tommaso Fabris, known online as “tommygondolier,” is one of them. On a summer weekday, he guides his gondola through narrow canals, pointing out hidden corners and details. “I am proud to be an ambassador of my city,” he tells me. His rides are often punctuated by mini lessons in Venetian history and culture. As Andrea Balbi, president of Venice’s Gondolier Association, relayed to me emphatically: “Tradition, for us it’s important—our job started a thousand years ago. We can’t lose this tradition.”Starting at the historic traghetto stazione San Toma, Fabris deftly maneuvers the gondola farther and farther from the Grand Canal’s tourist throngs, until he reaches the Dorsudoro district, birthplace of the iconic gondola and one of his favorite routes. “This is Venice,” he says, stooping below bridges and posting off the side of ancient red-bricked buildings.

Gondoliers start their careers cleaning boats. “You must learn about the gondola, how to park it, how to open it, how to clean it,” all before learning to row one, Fabris explains. As he calls out to passing boatsmen in lilting Venetian dialect, he recalls his first few years cleaning gondolas as some of the most memorable of his 17 on the canal.

Further, gondoliers must understand the construction of a gondola. No two are alike; each is built from roughly 280 pieces of eight different types of wood, “connected like a big puzzle,” according to Balbi. Balbi’s friend and fellow gondolier Tommaso Luppi tells me about summers as a schoolboy spent painting gondolas with a gondolier’s grandson, turning them into fishing vessels when tourist traffic was low.

But training extends beyond cleaning, rowing, and even navigating. Aspiring gondoliers undergo rigorous training in languages and Venetian history, art, and culture, and must also take a practical exam, which requires them to row from the front—which, as anyone who’s even been in a canoe knows, is a much more difficult position to steer from, and the forward weight distribution increases your chance of tipping. Last year, some-200 candidates applied to be gondolieri, but only 58 passed.

Then, the next set of challenges arrives: eager tourists who splash water, put their feet on the cushions, and move awkwardly around the boat—resulting in capsized gondolas and soaked occupants. “Don’t change seats without asking,” Fabris adds. And the question that annoys him most? “Do people actually live in Venice?” he laughs. (Yes, some 50,000 people live in Venice full-time.)

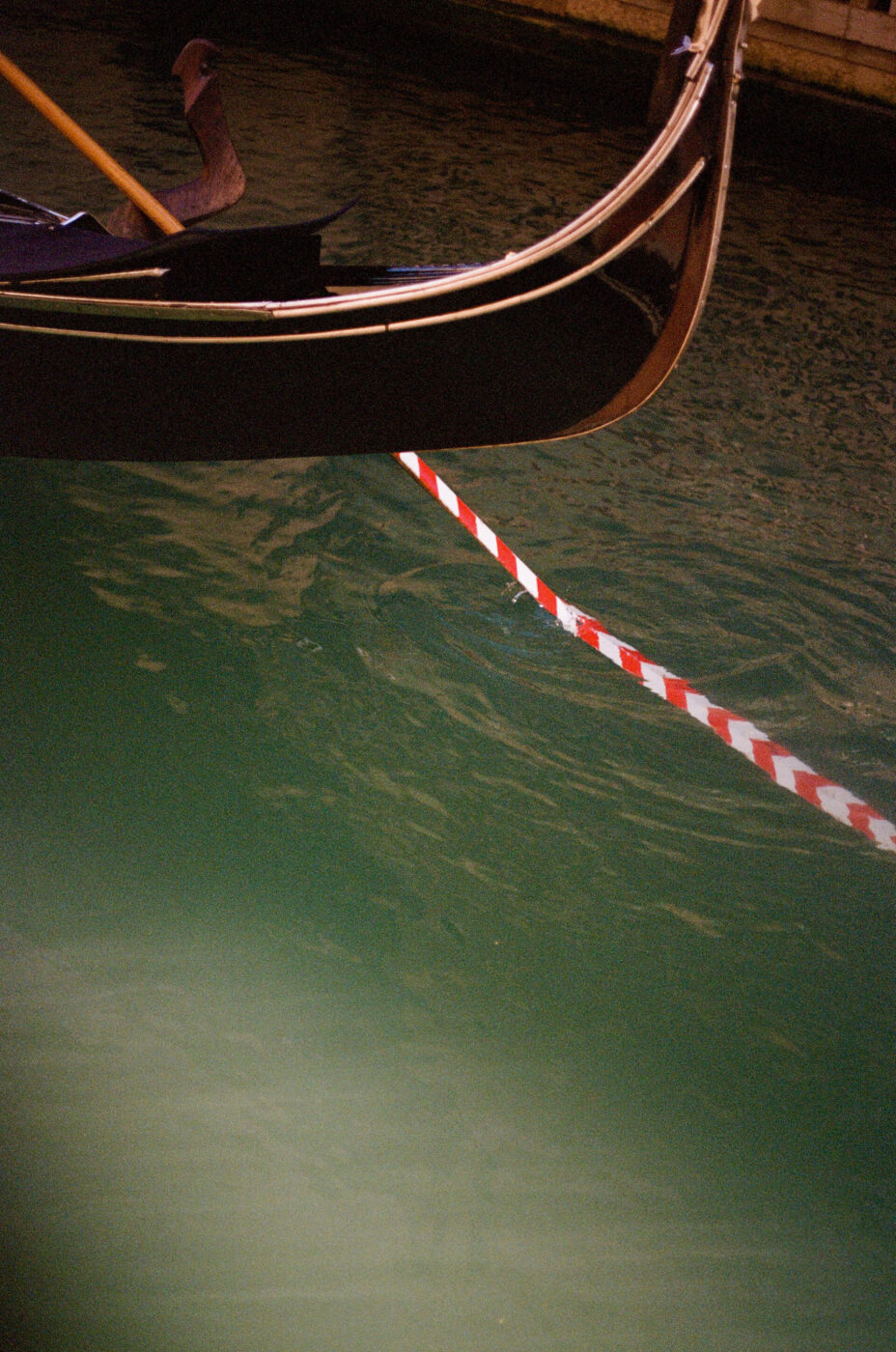

Gondolas’ primary passengers haven’t always been out-of-the-know tourists, however; at the height of the Venetian Republic, gondolas were most often private modes of transportation for the rich and noble. First mentioned in a 1094 Doge decree, early gondolas were flat-bottomed and required two oarsmen to transport wealthy owners across the lagoons. By the 1600s, their shape evolved into the graceful silhouette we recognize today, a change that improved balance and maneuverability and that better accommodates a single skilled oarsman, according to Balbi.

Why the elegant black hue? Fabris merely shrugs. He offers a popular legend: the color was adopted as a segna di lutto, or sign of mourning for victims of the Black Plague—very dark academia. But, more likely, it goes back to 1562, when the Doge and Venetian Senate issued an order banning extravagant decoration—an attempt to end the ostentatious competition between the wealthiest Venetian families—followed by decrees enforcing uniformity and simplicity. Black, ever in fashion, became the mandated color.

Each boat is purchased, personalized, and maintained by its gondolier, and I spot the names of Fabris’s two sons engraved into the interior side panels. “We are the symbol of Venice,” Luppi shares with me. “You mean the boats?” I try to clarify. “No, we and the boat are the same thing.”