The Roman Forum teems with boisterous citizens. Roman soldiers, clad in gleaming armor, line the streets to contain the crowd, while Julius Caesar—draped in a purple toga—surveys from a terrace above. Behind him stand senators, dignitaries, and stately matrons. A distant rumble builds, growing louder until massive drapes part to reveal the start of a glorious procession: soldiers, horses, dancers, musicians. Sound, color, and the opulence of a distant land flood the forum—a dazzling contrast to Rome’s austere grandeur. As the cortege slows, dozens of slaves appear, marching in perfect rhythm, pulling a monumental black sphinx through the jubilant throng. Atop it, cloaked in shimmering gold, the Queen of Egypt sits regally, towering above the crowd—commanding all eyes, all attention.

This extravagant scene from Joe Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra (1963) made Hollywood history. The lavish costumes, monumental sets, and thousands of extras—not to mention the peerless glamor of Elizabeth Taylor—set a bar so high that few films in the genre have matched it since, securing the film’s place as a cinematic legend.

Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra, trailer still for the 1963 film; Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

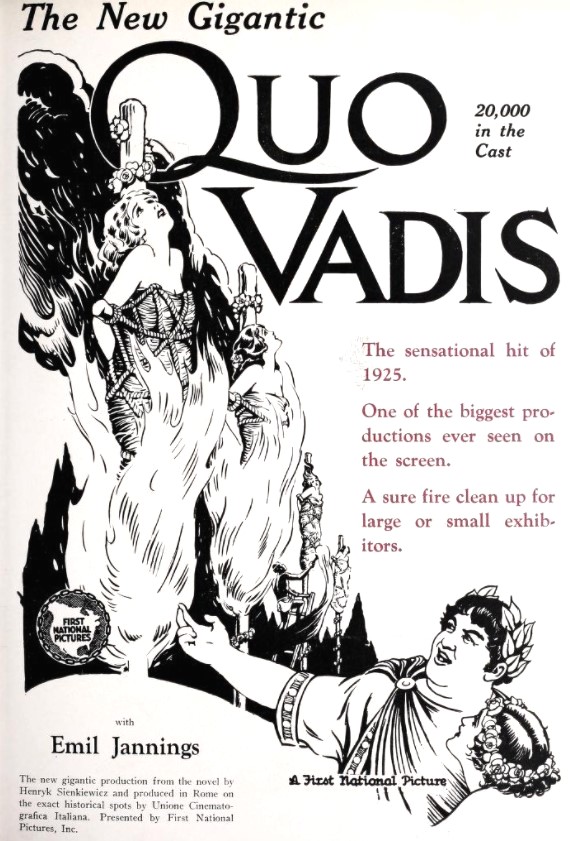

That genre is Sword and Sandal—a type of movie, set in Biblical or Greco-Roman antiquity, that has existed for over a century, from the silent era to Ridley Scott’s recent Gladiator II. After fading in the late 1930s and ’40s, its popularity roared back in the 1950s, reaching its peak with classics like Mervyn LeRoy’s Quo Vadis (1951) and Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960).

Sword and Sandal films turned antiquity into eye candy. Often backed by exorbitant budgets, Hollywood directors pulled out all the stops: real silk tunics and chiseled armor, sprawling battle scenes, lavish sets complete with elephants and other wild beasts, Roman senators lounging in Beverly Hills-style villas—swimming pools included.

In a curious twist of fate, these American productions ended up reconstructing Ancient Rome just miles from its actual ruins. Lured by generous tax incentives and the skilled, low-cost labor of Cinecittà Studios, Hollywood in the 1950s set up shop “on the Tiber.”

This Technicolor version of Ancient Rome favored exhibitionism over historical accuracy. Take Cleopatra: never mind that its Roman Forum is three times the size of the real one. More amusingly, the queen’s dramatic entrance—parading through the Forum like a conquering goddess—would have been flat-out illegal. Roman law forbade foreign rulers from entering the Forum, especially accompanied by their armies. As for her triumphal glide beneath the Arch of Constantine, recreated in full scale for the scene? A charming touch—if only the arch hadn’t been built three and a half centuries after her first visit to Rome.

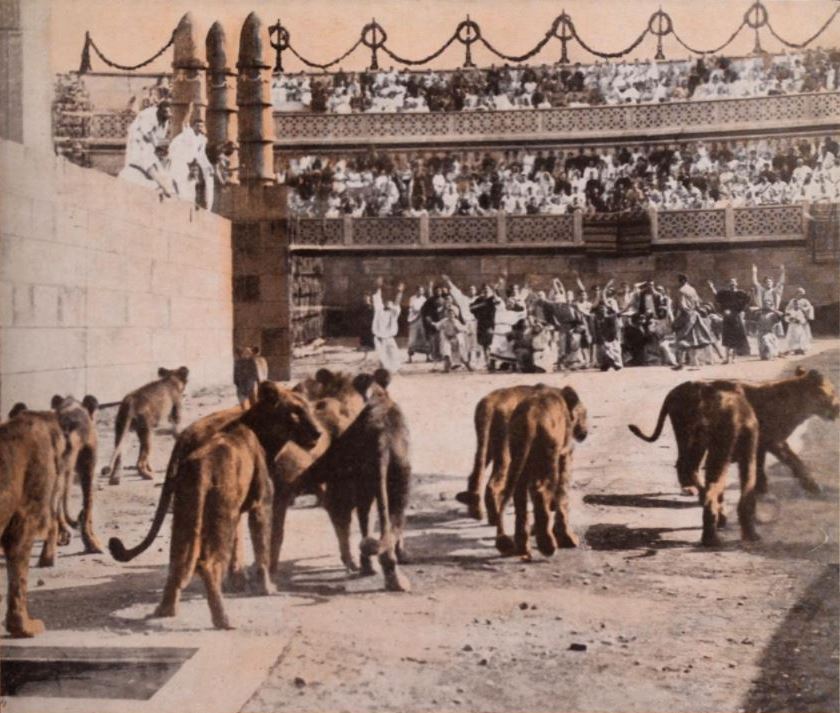

Tinted still used in an American advertisement for Quo Vadis (1913); Società Italiana Cines / Kleine Optical Company (U.S. distributor), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

And what to make of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000) and its sequel Gladiator II (2024)? Professor Kathleen Coleman, Harvard’s foremost expert on ancient arena spectacles and the historical consultant for the first film, became so disillusioned with the production that she requested her name be removed from the credits. Perhaps it was the scene in which Roman warriors slaughter each other with medieval crossbows. Or maybe it was the moment the filmmakers asked her to provide historical evidence that female gladiators affixed sharpened razor blades to their nipples. Gladiator II takes the whole debate on verisimilitude to the nth degree, featuring printed newspapers and great white sharks prowling a flooded Colosseum.

Bladed nipples or not, historical accuracy has never been the primary concern of the Sword and Sandal genre—neither in the 1950s nor today. The Rome it portrays is rutilant, majestic, and impeccably organized, yet also deeply corrupt and prone to vice and decay. Much of that characterization rings true—and remains relevant today (I just wish we had retained the organizational skills of our ancestors). But, in the end, sticking to the facts is beyond the point, for these films reveal far more about the era and culture that created them than about the ancient world they claim to depict.

Following a convention used in the 1950s to be more relatable to American audiences, British Commonwealth actors were typically cast as the upper-class, villainous Romans, while Americans played their ethnic or religious adversaries. In William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959), for instance, the ruthless Roman general Messala is portrayed by Irish actor Stephen Boyd, while the Jewish hero Judah Ben-Hur speaks in Charlton Heston’s unmistakably broad Midwestern American accent.

Unsurprisingly, Ancient Rome carries different political weight in the Italian iteration of the Sword and Sandal genre, known as Peplum—a name derived from the short tunics sported by its sandal-strapped heroes. (I suspect the Latin terminology serves to remind the rest of the world of our ancient, and impeccably fashionable, ancestry.)

American advertisement for Quo Vadis (1924); Unione Cinematografica Italiana / First National Pictures (U.S. distributor), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The rise of Italy’s own sub-genre began with Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914), widely considered the first major Roman historical epic in cinema. The film’s intertitles were penned by none other than Gabriele D’Annunzio, whose ornate poetry is on full display. One of the finest examples is an invocation to the god Pluto: “O sceptre God, you who placed your throne in the abyss, you who clench the roots of the Earth, you who kidnapped Demeter’s daughter from her Sicilian meadow…”—and so on, for a good ten minutes. By comparison, the grandiloquent speeches that recently turned our current Minister of Culture into a meme feel like minimalist compositions.

Staying on topic, one of the first films produced under Fascism was Carmine Gallone’s Scipione l’Africano (1937)—a pompous piece of political propaganda designed to justify Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia, launched two years prior. The parallel is anything but subtle: the Ancient Romans stand in for the Fascist army, while the Carthaginians clearly represent the Ethiopians. Scipio, portrayed by Annibale Ninchi, mimics Mussolini in both body language and speech, while the Carthaginians are often costumed in uniforms resembling those of 1930s Ethiopian soldiers. Fasces—the emblem of Fascist authority—are prominently displayed, frequently borne beside the Roman general as he carries out his imperial mission.

Scipione being greeted with the Roman salute in Scipione l'Africano (1937); Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

From Decadentism to dictatorship and beyond, Italian Pepla recycled themselves so many times that by the 1960s, it became a B-movies genre—starring improbable American bodybuilders as their heroes. Whether named Goliath, Ursus, Samson, Hercules, or Maciste, the protagonist was always some variation on the same archetype: a brawny, not-too-psychologically-developed strongman who battles injustice and crushes anything that threatens the law.

Scholar Maria Elena d’Amelio has brilliantly interpreted the hyper-physicality of actors in these films as a cinematic materialization of the American dream. “Everywhere he goes, Hercules is always greeted and acclaimed by the people, who recognize him for alleviating their daily toils. Just as the Marshall Plan was presented as the only way to liberate Italy from poverty and backwardness, Hercules frees his subjects from the hardest physical labors and helps them rebuild their country,” she argues.

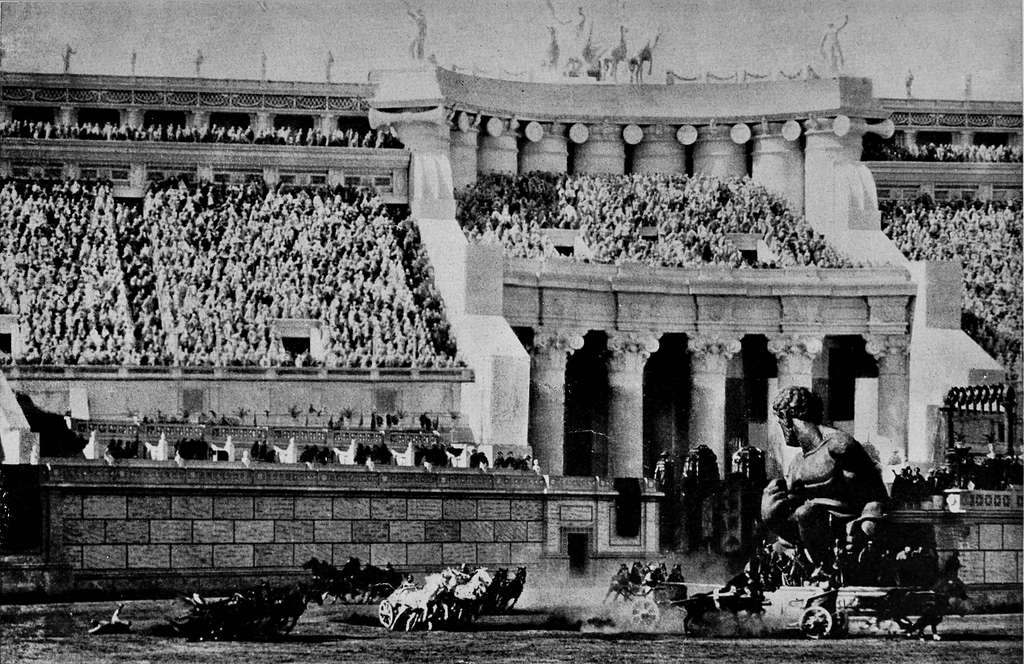

Scene from Ben-Hur; Touring Club Italiano, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

All this goes to show that, beneath their façade of harmless entertainment, Sword and Sandal films harbor intricate cultural dynamics. Italian Pepla helped the nation navigate the difficult transition from Fascist dictatorship to democracy in the aftermath of World War II, reflecting Italy’s evolving relationship with American culture and the impending economic changes of the 1960s. By contrast, the American iteration of the genre, set against the comforting backdrop of a distant past and faraway lands, became a vessel for society’s more uncomfortable aspects—politics, sexuality, and racism—too taboo to be directly confronted. At worst, these films reinforced prevailing prejudices. But on occasion, some slipped past the era’s strict censorship—and managed to subvert expectations in unexpected ways.

With few exceptions, female characters in both Pepla and Sword and Sandal films are relegated to secondary roles—and invariably appear on screen wearing little to nothing. In many productions, Ancient Rome’s cosmopolitanism becomes a convenient excuse for inserting sequences of pure spectacle: elaborately staged dances performed by people of color to frenzied drumbeats, reinforcing racist stereotypes rooted in the Orientalist worldview prevalent at the time. A rare departure from this pattern appears in Spartacus, in which African American actor Woody Strode plays Draba, a gladiator embodying nobility and dignity—a quietly radical moment in a genre otherwise steeped in caricature.

Although sparse, allusions to the United States’ political climate of the 1950s in some Sword and Sandal films are hard to miss.

In Ben-Hur, the scene in which a vengeful Roman general pressures the protagonist to name Jews disloyal to the Empire unmistakably echoes the McCarthy-era witch hunts, when Americans were coerced into identifying suspected Communists. Among those blacklisted was writer Howard Fast, who penned the novel Spartacus while imprisoned in 1951 for his Communist sympathies. Inspired by the slave revolt led by the Thracian gladiator around 73 BC, Fast’s book became a sensation. Its film adaptation, released nine years later, was met with boycotts and condemnation from conservative and religious groups, who branded it anti-American. That Karl Marx once described Spartacus as “a real representative of the proletariat of ancient times” likely didn’t help its case.

A pivotal moment came when President John F. Kennedy attended a public screening of Spartacus in Washington. His presence, coupled with the film’s box office success, helped legitimize it in the public eye—and marked a symbolic end to the Hollywood blacklist.

Scene from "Son of Spartacus"; Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

But the Sword and Sandal genre delivers its most satisfying material when it comes to homoeroticism. Probably inspired by the close-knit camaraderie of Roman legionnaires or by the mere thought of half-naked men wearing leather mini-skirts, allusions to male desire come back and back again in these films. Not without complications, of course. In many, queerness is coded onto the villains—typically emperors—who are portrayed as weak, sick, and promiscuous men corrupted by power and vanity. Think of Peter Ustinov’s uber-camp portrayal of the deranged Emperor Nero in Quo Vadis—a performance as delightful as it is stereotypical. Or the similar characterization of Emperor Commodus in Gladiator, whose boyish face, smooth physique, dapper appearance, and tormented persona stand in pointed contrast to the straightforward and rugged masculinity of the film’s hero, Maximus, played by Russell Crowe.

Gladiator II reiterates such tropes, staging the pair of unhinged imperial brothers—Geta (Joseph Quinn) and Caracalla (Fred Hechinger)—against the straight-coded characters of Lucius Verus Aurelius (Paul Mescal) and General Acacius (Pedro Pascal).

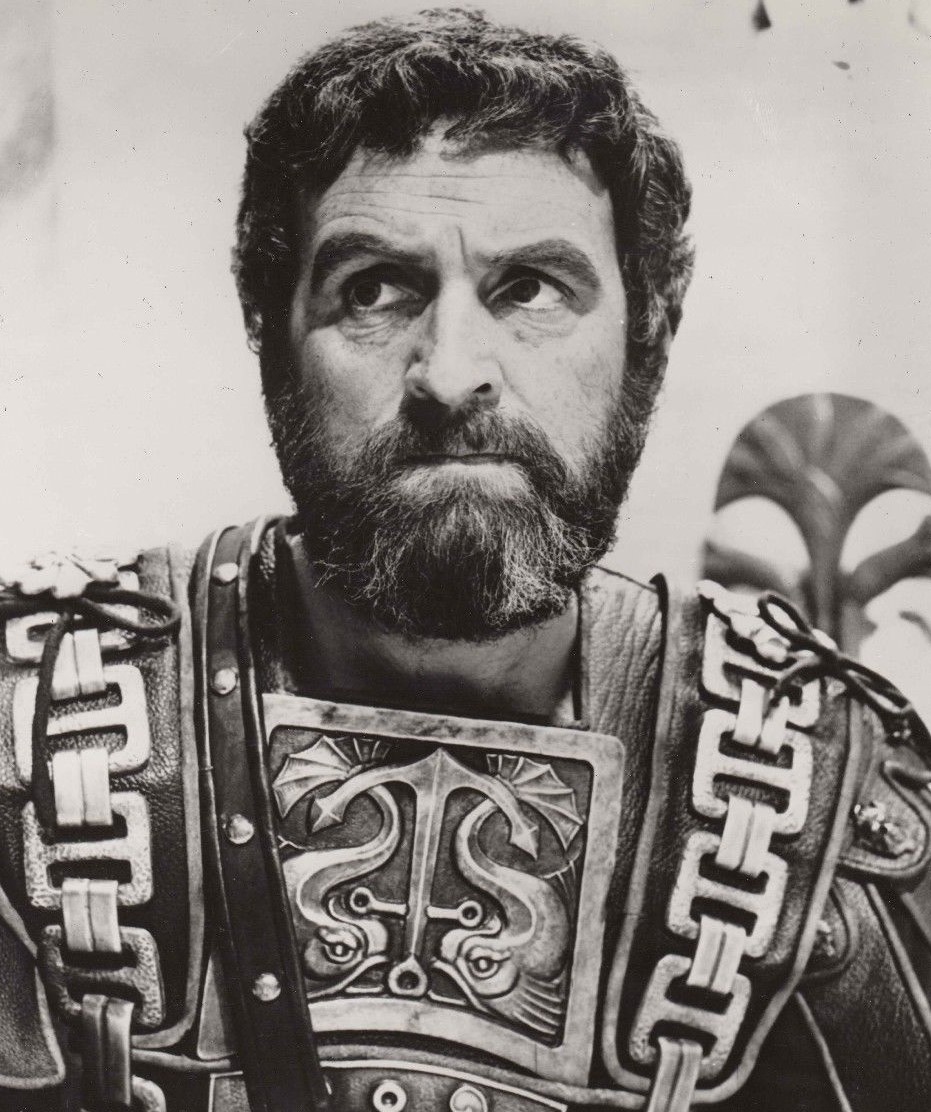

Andrew Keir in Cleopatra (1963), looking uncannily similar to Paul Mescal and Pedro Pascal's characters in the recent Gladiator II; unknown (20th Century Fox), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

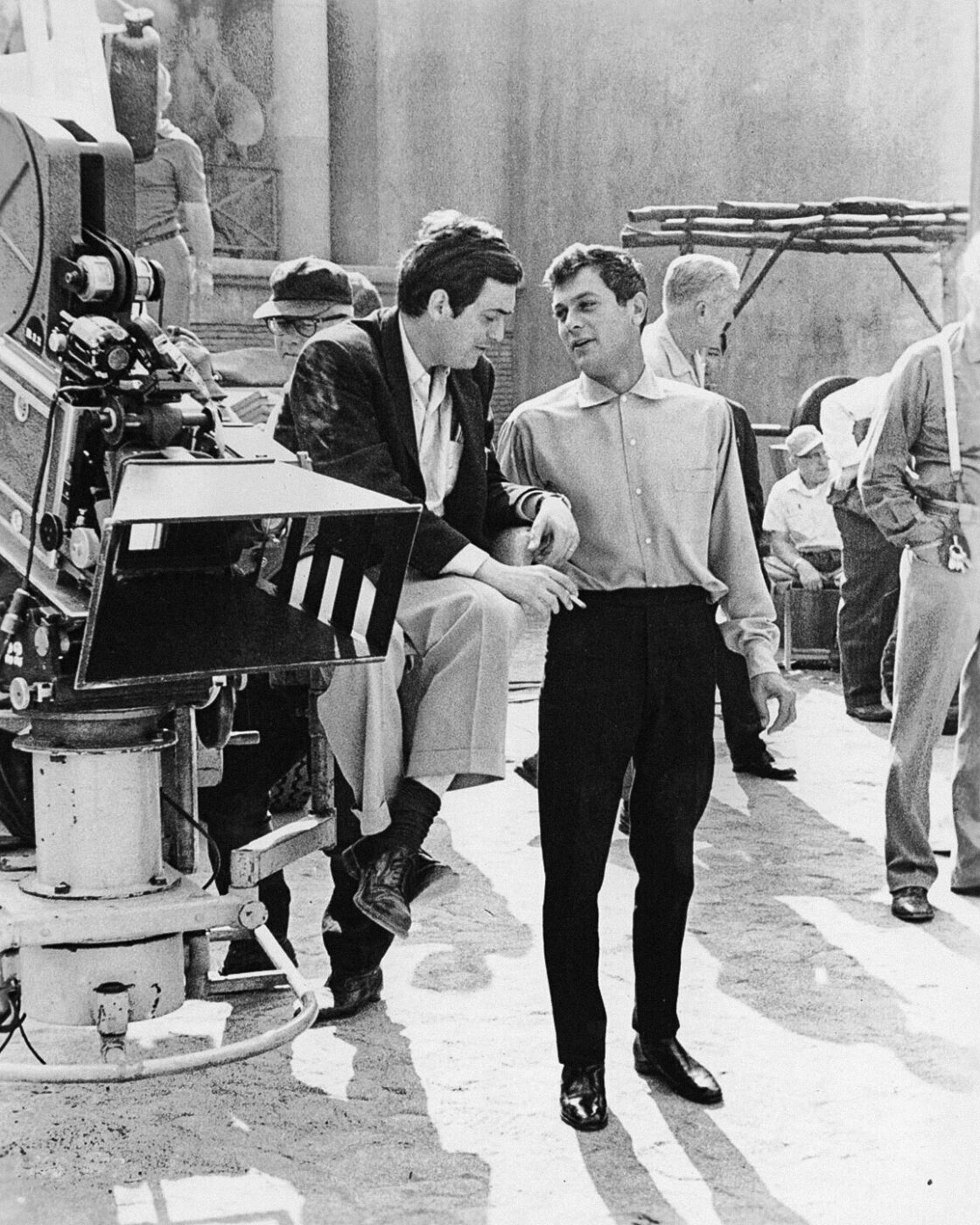

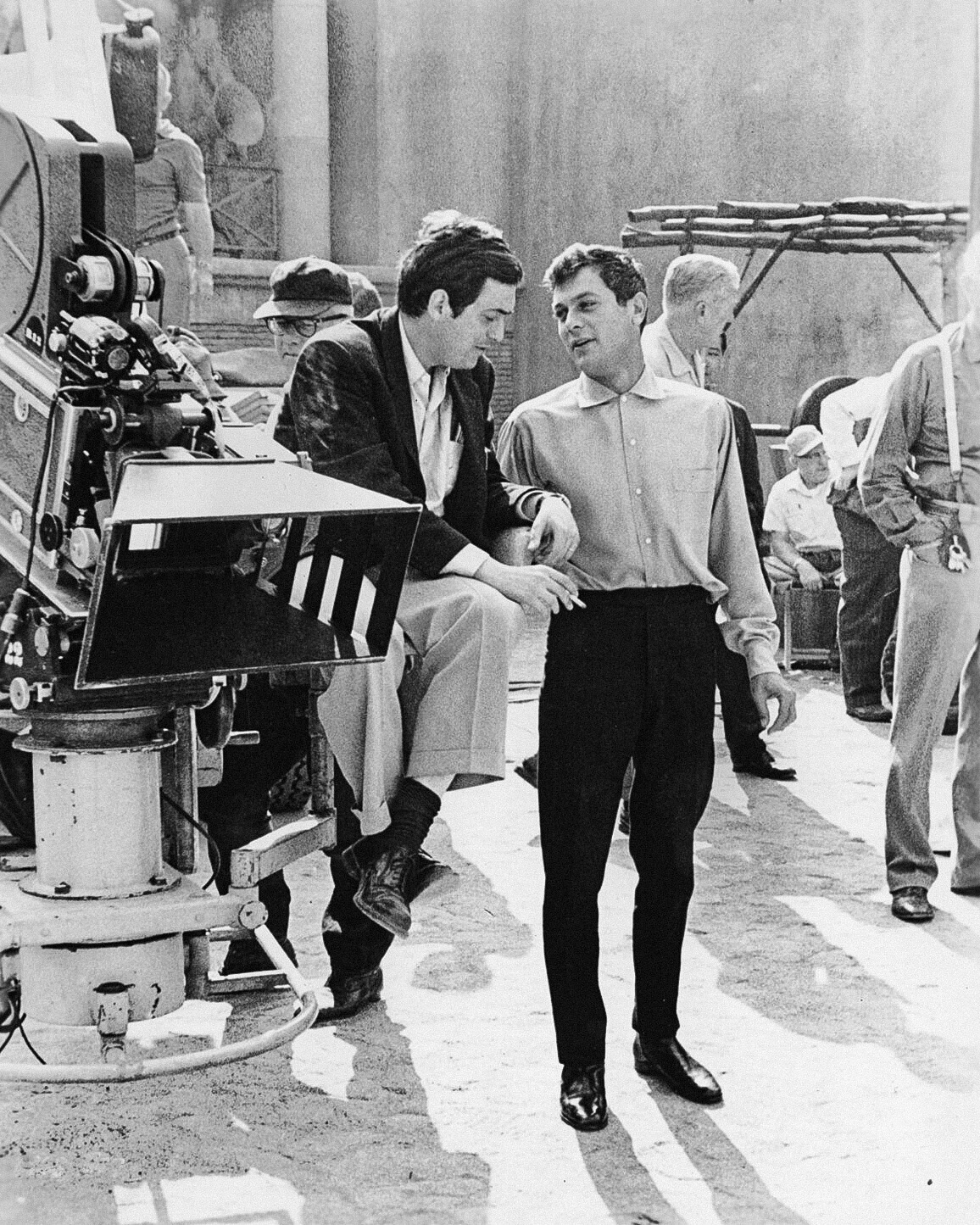

Roman baths, gym culture, and well-oiled bodies clearly left a lasting imprint on Hollywood’s imagination, and few scenes capture this better than the infamous “oysters and snails” exchange in Spartacus—a moment that could easily have been lifted from 1960s gay soft porn. In the scene, Roman general and film antagonist Crassus—played with sly elegance by Laurence Olivier—is bathed by his young slave Antoninus (Hollywood’s darling Tony Curtis). Crassus carefully reveals his bisexuality through metaphor, explaining that he enjoys eating both “oysters and snails.”

“Do you consider the eating of oysters to be moral and the eating of snails to be immoral?” he asks. The sequence was cut entirely from the film’s original release; later versions have restored it.

Kubrick and Curtis on the set of Spartacus (1960); Public Domain, via Internet Archive

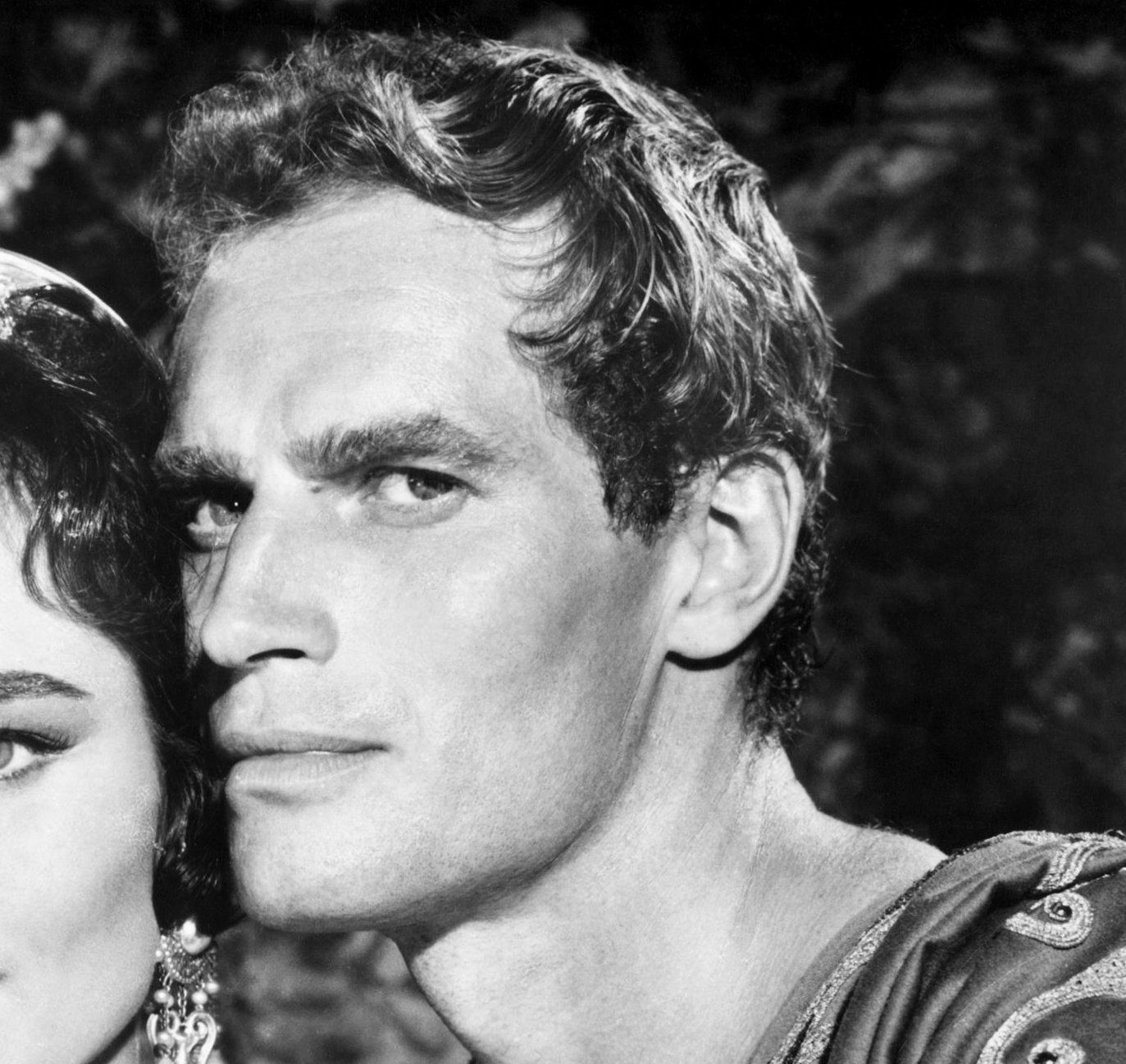

Homosexual subtext reaches an entirely new register in Ben-Hur, however. The film opens with Roman aristocrat Messala, played by Stephen Boyd, returning to Judea as an imperial administrator. There, he reunites with his childhood friend Judah Ben-Hur, a Jewish prince portrayed by Charlton Heston. But their friendship unravels when Messala asks Judah to help him suppress Jewish dissidents.

Screenwriter Gore Vidal suggested to director William Wyler that the relationship between Messala and Judah be played as though Messala were attempting to rekindle a youthful love affair. This framing, he argued, would lend Judah’s rejection—of both Messala and his politics—a deeper emotional weight, infusing their rivalry with the sting of a spurned lover. Wyler agreed but feared that Charlton Heston, known for his conservatism, might walk off the set if he caught wind of the subtext. The solution was that Boyd, and the rest of the cast, were let in on the interpretation, while Heston was left in the dark. The result is a charged tension that vibrates just below the polished veneer of swordplay and politics.

“Is there anything so sad as unrequited love?” Messala pointedly asks Judah at the climax of the movie.

Publicity still of Charlton Heston for Ben-Hur (1959); unknown (MGM), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s a reminder that even in films set thousands of years ago, the real drama often lies in the concerns of the present.

Technology has forever transformed the way epic films are made. Gone are the months-long shoots for just one scene, the armies of extras, the plasterboard colossi. At the same time, our society has evolved—reexamining its views on otherness, women’s bodies, and queer identities.

And yet, our image of ancient Rome remains stubbornly shaped by Hollywood directors and screenwriters who, more invested in spectacle than accuracy, projected their own political and social anxieties onto the distant past. Perhaps we’ve come too far inside this imaginary world to ever fully shake it; Rome as cinema has eclipsed Rome as history. But if we’re destined to keep revisiting the empire on screen, why not reimagine it with fresh eyes?

In today’s film industry, dominated by remakes, prequels, and sequels—ones in which sharks are free to swim inside the Colosseum—there’s certainly room for a post-Stonewall, post-gender version of Ben-Hur, in which Messala and Judah can finally come out of the closet.

Netflix, thank me later.