Diamonds certainly were the Renaissance woman’s best friend. Unlike us modern women, upon which jewels are relegated to the ears, neck, wrist, and fingers–how banal!–wealthy women of the 15th and 16th centuries were positively dripping in them. Pearls, sewed into hair pieces, cascaded down braids. Garnets and opals cinched waists in the form of corsets. Necklaces of rubies, amethysts, sapphires, emeralds were worn layer upon layer. Anything that could be bejeweled was.

Nowhere was this more so the case than in Florence, under the reign of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. During the Renaissance, jewelry design reached a level of expression comparable to that of the figurative arts (the likes of which hadn’t been seen since the Hellenistic period), with there being no discernable divide between the two art forms. Almost all of the greats behind the Renaissance artistic revival, at some point in their careers, worked or apprenticed in goldsmithing workshops where the gents of the town would have their hat medallions made and where the ladies would set pieces of their wardrobes with all varieties of glittering jewels–among them Brunelleschi, Botticelli, and Lorenzo Ghiberti. Even Michelangelo is said to have studied the jewelry of his benefactors, the Medici, taking inspiration for his paintings.

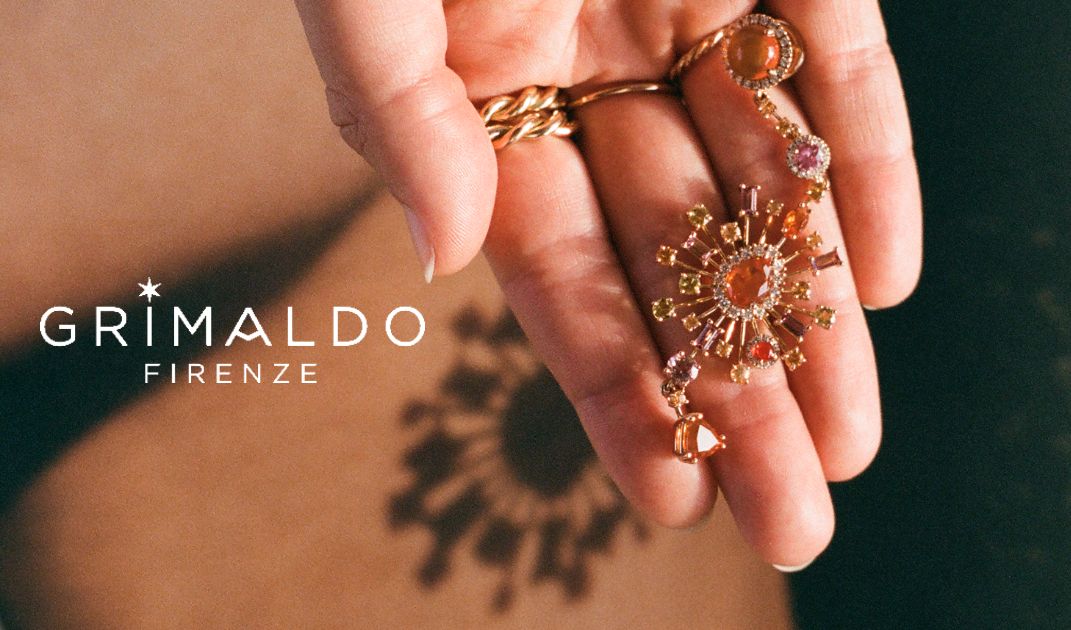

“The interesting thing about that particular period is that it was not just about collecting gems with a high value–which has always been the core of jewelry design–but that [jewelers] started doing work on combinations,” says Elisa Casini, the jewelry designer behind Florence’s Grimaldo, whose work is very much inspired by Renaissance collections.

The pendant was the ultimate showcase for the creativity and technical skill of Renaissance artist-jewelers. Initially, these pendants featured decorative medallions containing cameos, an engraved gemstone or shell featuring Classical motifs like mythological or religious figures–not just decorative but statements of intellectual and cultural sophistication. Over time, the pendants were embellished with multicolored gold, enamel, and gems, evolving into elaborate, openwork pieces depicting a wide range of subjects—animals, Tritons, mermaids, ships, sea monsters, etc.—often using the irregular shape of baroque pearls to form bodies or torsos in imaginative compositions. Beyond pendants, rings gained widespread popularity during this time, many featuring bezels that could be opened to hold little relics or, as legend suggests, even poison. Because of the intricate craftsmanship behind necklaces, rings, and brooches, the artistic value of these pieces far exceeded the worth of the materials used to create them.

As was often the case back then, royalty got competitive, with the courts of England, France, Spain, the Duchy of Burgundy, and the Duchy of Tuscany engaging in lavish contents to outshine one another with their displays of gold, gems, and pearls; the nobility and other affluent society members followed suit. “Jewelry was not only used as an indicator of status, but to adorn the person through design,” Casini explains, pointing out that wearability was of high importance to members of these courts. “Compositions were designed to cover large amounts of the body–belts, crowns, large choker-like necklaces, hair pieces with pearls and precious stones, even embroidered into clothing, like corsets. A piece of jewelry could be something far beyond the jewels even.”

The winner of these “competitions” was most always the Duchy of Tuscany. Florence was the cradle of the Renaissance, after all, thanks in large part to the ruling Medici family. First obtaining their wealth from banking, the Medici were, for a time, the richest family in the world–adjusting for inflation, their net worth would be something like €117 billion ($129 billion)–and they were happy to spend their cash. “The Medici were not just a wealthy family, but one that invested so much in art and craftsmanship, something that’s beautifully portrayed all over their history,” Casini says. “Portraits show this off and [display] how long this heritage lasted.” A quick search online of Caterina de Medici is enough to see just how bedecked she was.

Caterina De Medici

The Medici, in fact, were once owners of the most valuable diamond to have ever existed: the legendary, irregularly-shaped Florentine Diamond. A yellow diamond of approximately 137 carats, the Florentine Diamond was famed for its pale, greenish-yellow hue and elaborate double rose cut. Originating from India, it is believed to have passed through the hands of several European rulers, including the Medici family, who prominently displayed it as part of their regal collection. After the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the diamond was taken to Switzerland, but it mysteriously disappeared in the early 20th century; its whereabouts remain unknown to this day. A shame–though plenty of the family’s jewels have lived to tell the tale and can be found in museums (in Florence, Casini recommends checking out La Specola, a mineral exhibition that was one of the first to open for public display, and the jewels collection of Palazzo Pitti, the Medici’s former residence).

What else has lived to the tale is the tradition of jewelry making in the Renaissance city–and we’re not talking about Ponte Vecchio. There are still plenty of small, family-run ateliers like Grimaldo that follow in the footsteps of their Florentine ancestors with innovative design and combinations. “Nowadays, the traditional approach to creating something valuable involves placing a large, high-value stone at its center. Personally, I love working with intricate compositions of gemstones,” Casini says. And, in homage to the city that inspires her most, she sometimes hides a Florentine giglio within the dangling amethysts of chandelier earrings or the garnets of a Baronesse ring.