As most millennials, I have often had to make do by working odd jobs that had little to do with my university studies. One of the most random, and yet absurdly incredible, of these was working at the front desk of the Grand Hotel in Rimini.

Yes, that one, Federico Fellini’s second home.

Federico Fellini, a towering figure of the 20th century and one of the greatest directors of all time, is indelibly linked with the glittering heyday of Rimini, when the Romagna Riviera attracted hordes of tourists and members of the international jet set for its discos and lidos. Much of the region’s appeal, which still echoes today, can be attributed to the charisma of Fellini and the mark he left on this slice of Italy.

Fellini was born in Rimini in 1920 and grew up in the coastal city until 1939, when he moved almost-permanently to Rome. However, the Rimini of his childhood and adolescence will often return in his films–with a twist from his fairytale imagination–and the city’s magnificent Grand Hotel will be one of the places most dear to the director, a place he will stay at several times a year from the 1950s until his death in 1993.

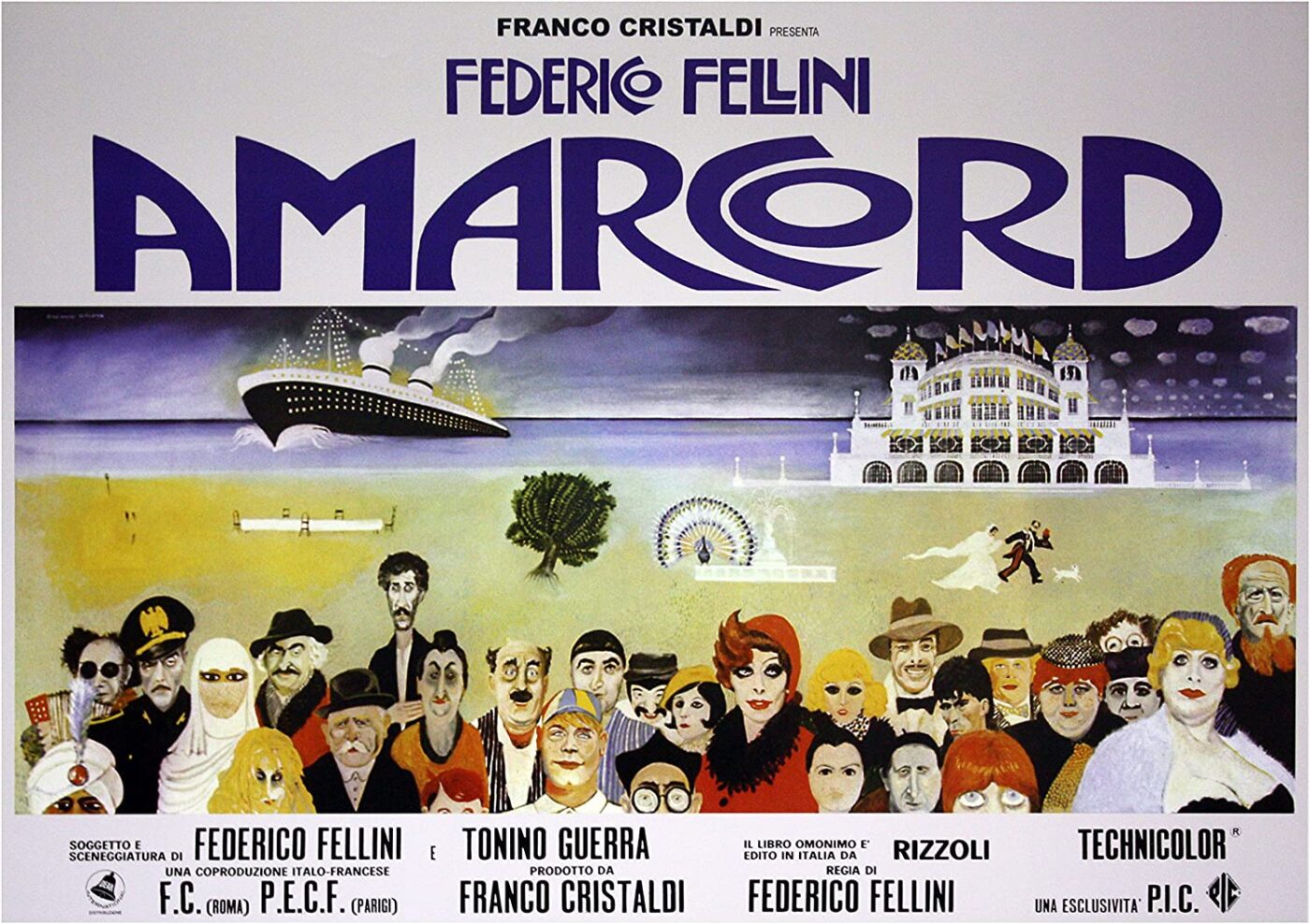

Since the year of its inauguration, 1908, the Grand Hotel represented the height of extravagance and luxury. We can imagine a young Fellini admiring, outside its gates, the two now-nonexistent Arabian domes, the lush gardens, the terrace illuminated by a thousand lights, the Liberty facade–just as Titta Benzi does in the film Amarcord, spending hours and hours spying on the extremely elegant and wealthy guests through holes in the hedges.

When I set foot in the Grand Hotel for the first time, I knew little about Fellini, but everyone who worked there had almost a religious reverence for him (it often happened that guests stayed there only because of Fellini’s name, as if they expected to see him live). When he returned to Rimini from Rome to visit his sister Maddalena and mother Ida, Fellini always chose to stay at the hotel he dreamt of as a child, not his childhood home, in the same suite: Suite 315 (which today, rightly so, is called the Fellini Suite and is only booked by the most affluent personalities)–this detail I had to learn brutally. On one of my first days at the hotel, a veteran member of the staff took all the novices out to the terrace, placed us in front of the facade and, pointing to the arched windows embedded between the two front pillars, said, “Better learn right away, because I don’t have time to waste. On the first floor, in the center, there is 115; above, on the second, 215; and on the third floor, 315, Fellini’s room. And that’s it, I won’t repeat it, but I’m sure the stupid ones will come and ask me again.”

Suite 315 opens up like a butterfly into the lateral wings–on one side, the also famous room 316 and on the other, a huge master bathroom. With a small balcony overlooking the terrace, the sea and the garden, these are the most coveted rooms (and obviously, the most expensive–at least €1,000/night, if not more). The décor is Art Nouveau with Persian carpets, Murano chandeliers, very fine antiques and a parquet floor from the beginning of the 1900s.

During the months I worked there, I saw VIPs like Kanye West, Santana and Vasco Rossi pass through those suites. And there’s a whole host of important personalities of the past who slept there: Pavarotti, the Dalai Lama, the Queen of Saxony, King Faruk, the Duke of Abruzzi, Eleonora Duse, Lady Diana, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Pietro Mascagni, Rita Levi Montalcini, Pedro Almodovar, Enrico Caruso… I could go on for hours and hours and still not finish the list.

The assignment of that specific suite to Fellini was the work of actor and entrepreneur Cavalier Pietro Arpesella, the owner at the time, who had formed a close friendship with the director.

But this room wasn’t the only place in the hotel taken over by Fellini: he was often seen on the terrace–sitting on the indestructible, white wrought iron chairs writing–and in the large hotel halls eating fish stew, one of his favorite dishes, or saffron risotto with two drops of grappa, now punnily named on the menu as “Ris’otto and a Half”. Or he often stopped to sit on the circular sofa in the lobby, in front of the window that leads to the terrace and garden, to draw the hotel guests: a lady with perfectly-trimmed, little dogs in tow; an elegant man in a hat; a couple arm in arm with luggage; the hotel waiters, stiff in their dark uniforms, serving tables covered with immaculate tablecloths; sketches of his favorite women, always voluptuous; and drawings of the circus world (for which he had a very strong attraction), of the sky and the moon, of dreams and fairy tales.

On this subject, I have a treat just for insiders: for years, a huge volume containing Fellini’s drawings and sketches (or rather, copies of them) has been kept at reception. Every guest can still view the book at will. It was thanks to these drawings that I was able to better understand Fellini’s personality and his attachment to Rimini and the Grand Hotel: in his nervous, caricatural stroke, in the garish colors, one can feel an almost childlike, exotic joy towards that place which so captivated him as a child.

Isn’t the adjective “felliniesque” used for all those films, those works, those dreamy, visionary, vaguely melancholic attitudes that followed in his footsteps?

By working in the same spaces where the director lived, walked and found inspiration, I learned of little stories and mannerisms: Fellini loved the comics of Stan Lee and, as a young man, used to go to the beach to offer sketches and caricatures to bathers and tourists for a few coins; Fellini did not disdain the company of beautiful women, especially those “abundant in side A and side B” (in fact, without using euphemisms, one could say he was a real womanizer–Anita Ekberg was one of his muses after all); Fellini also did not scorn the company of gurus and psychics, because he believed in the paranormal in his own way; despite his love for Rimini, Fellini did not shoot any films there (Amarcord is set in Rimini, but was shot entirely in Rome); while filming Amarcord, Fellini picked up a homeless man, Vincenzo Caldarola, and hired him for the role of the Grand Hotel’s Emir; Fellini’s hostility towards Luchino Visconti was legendary, perfectly reciprocated, and Marcello Mastroianni settled the matter: “Visconti is the professor that everyone dreams of having, while Fellini is the ideal friend.” After Fellini’s death, all the streets that lead to the city’s waterfront were renamed with the titles of his films.

To Fellini, the Grand Hotel was always linked to his childhood dream, that of stepping out of anonymity and becoming part of the glittering, fantastic world that inhabited the Grand Hotel, the world of the wealthy, the famous, the well-dressed, the powerful. As an insider, although I was only there for less than a year, I can confirm that the myth of Fellini still lingers, particularly among foreign guests. But the most enduring of his dreams are really those captured on paper and film. The Grand Hotel is just a door through which one can imagine a shining past and an even more promising future, just as Fellini did–a man of humble origins who dreamt of that magical place so much that he became an integral part of it.