While traffic clogs the sweltering streets of Rome, inside the Circolo Canottieri Aniene, peace feels almost ironic; in Italy’s capital of chaos, silence is a luxury. Beneath the shade of wild pines in this exclusive club where actors, politicians, and international managers gather, Giuseppe Maggio seems like a man from another time. His oversized forest-green cardigan hides a sculpted physique, like one of the statues at Palazzo Farnese. There’s nothing showy about him: he’s only 33, but carries himself like an actor from another era.

A classical high school education, a law degree—he follows the cursus honorum of a Roman nobleman from the 17th century. Maybe that’s why he loves Villa Borghese, that oasis of green and marble in Rome where time doesn’t pass but glides. He loves the parts of Rome that remind him of Paris—tree-lined avenues like boulevards—and that makes him different from so many Roman actors who are deeply rooted in the city. He has plenty of television shows under his belt, from Provaci ancora prof! to Netflix’s Baby, but it’s in cinema that Maggio truly blooms: somewhere between a promising young talent and a seasoned artist, well-read and deeply trained.

For someone so attuned to the echoes of history, it’s fitting that Maggio’s most demanding role to date delves into one of cinema’s darkest footnotes. In Being Maria (2024), Maggio plays Bernardo Bertolucci in a film that revisits what happened to 19-year-old actress Maria Schneider on the set of Last Tango in Paris. During filming, director Bertolucci and actor Marlon Brando orchestrated a simulated sexual assault without her full consent—conceiving the now-infamous butter scene without informing her beforehand. Their goal, as Bertolucci later admitted, was to provoke a real reaction on camera. The film, released in 1972, was seized for obscenity and condemned to be burned. But the deeper harm lay in what Schneider later described as a profound emotional betrayal—manipulated into performing a scene she didn’t fully understand, in a moment that would haunt her for years.

Anamaria Vartolomei as Maria and Giuseppe Maggio as Bertolucci in Being Maria

Giuseppe, what did you feel playing Bertolucci?

That scene, we now understand, was an abuse. But I have to say that playing Bertolucci didn’t make me feel uncomfortable. Bertolucci was a complex figure, and in portraying him, I became the interpreter of a particular story. This is part of my work as an actor. One can contest what happened in the past, but what matters, in the end, is that the actor always reads the script, studies, and is fully aware of the work they are doing.

Playing Bertolucci, for me, meant searching for the truth of a director who, in the ’60s and ’70s, fully lived through the student revolution and saw how the world was changing. And, with that scene, he wanted to punish the family, which was the core of bourgeois society. Unfortunately, and against her will, Maria Schneider became the expression of that bourgeois class that the director wanted to make relive a certain pain.

In Being Maria, the scene ends with Bertolucci calling “Cut!” What does that moment mean to you? Is it about separating art from morality?

Exactly. For me, it was very important to stand beside the “elephant” that is Bertolucci, to be guided by him. I couldn’t distort the telling of what happened with my personal judgment. Maybe that’s why I don’t love stories that focus so much on the discomfort some actors feel when portraying certain characters. If you choose to play a complex character, you have to fully embody their image—whatever the cost.

Today, many veteran actors revisit their past roles with a critical eye. What do you think about that?

People often want what they didn’t have. An actor at the height of fame might long for the artistic recognition they never received. It’s very human to always chase what’s just beyond your grasp. Still, at a certain point in your career, I think it’s important to value what you’ve accomplished—without too much moralizing. For example, I don’t understand why some actors look back and belittle their early work. Those first roles define the artist you become. Some start in soap operas or reality TV, and yet go on to achieve great things.

In an interview with L’Officiel, you mentioned Brad Pitt as a model—someone who intentionally shed the “pretty boy” label. Do you think young actors today are more willing to break free from typecasting?

Definitely. Society has changed. Today, male vulnerability is seen very differently than it once was. There used to be this ideal of hyper-masculinity—it was the ’80s, the era of power suits and shoulder pads. Today, men are more inward-looking, calm, even introverted. Cinema reflects that shift. For example, I’m thinking of Ms. Playmen, a Netflix series coming out this year about Adelina Tattilo, the director of a magazine with an English name but an entirely Italian spirit. It’s fascinating to explore how revolutionary even the past can be.

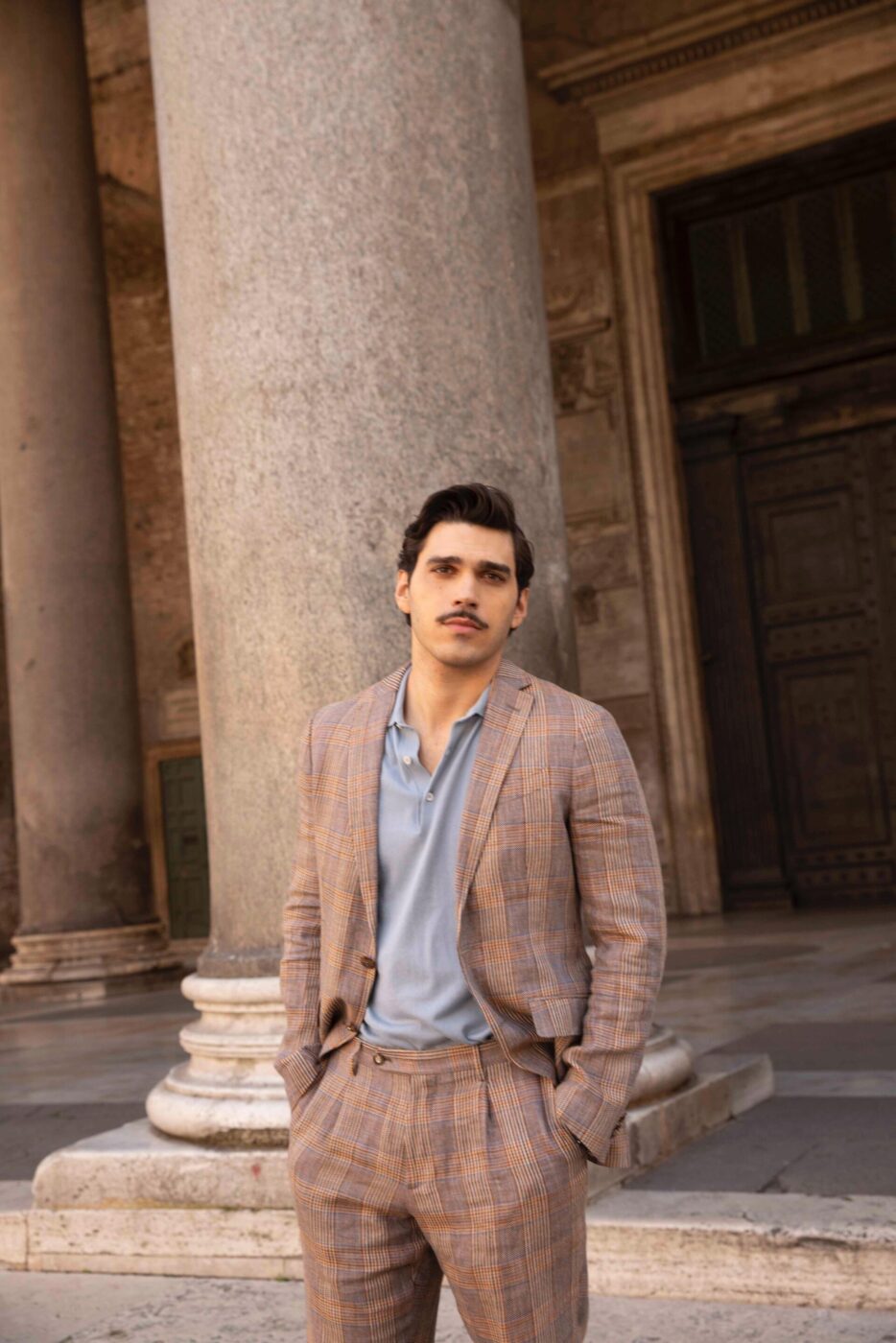

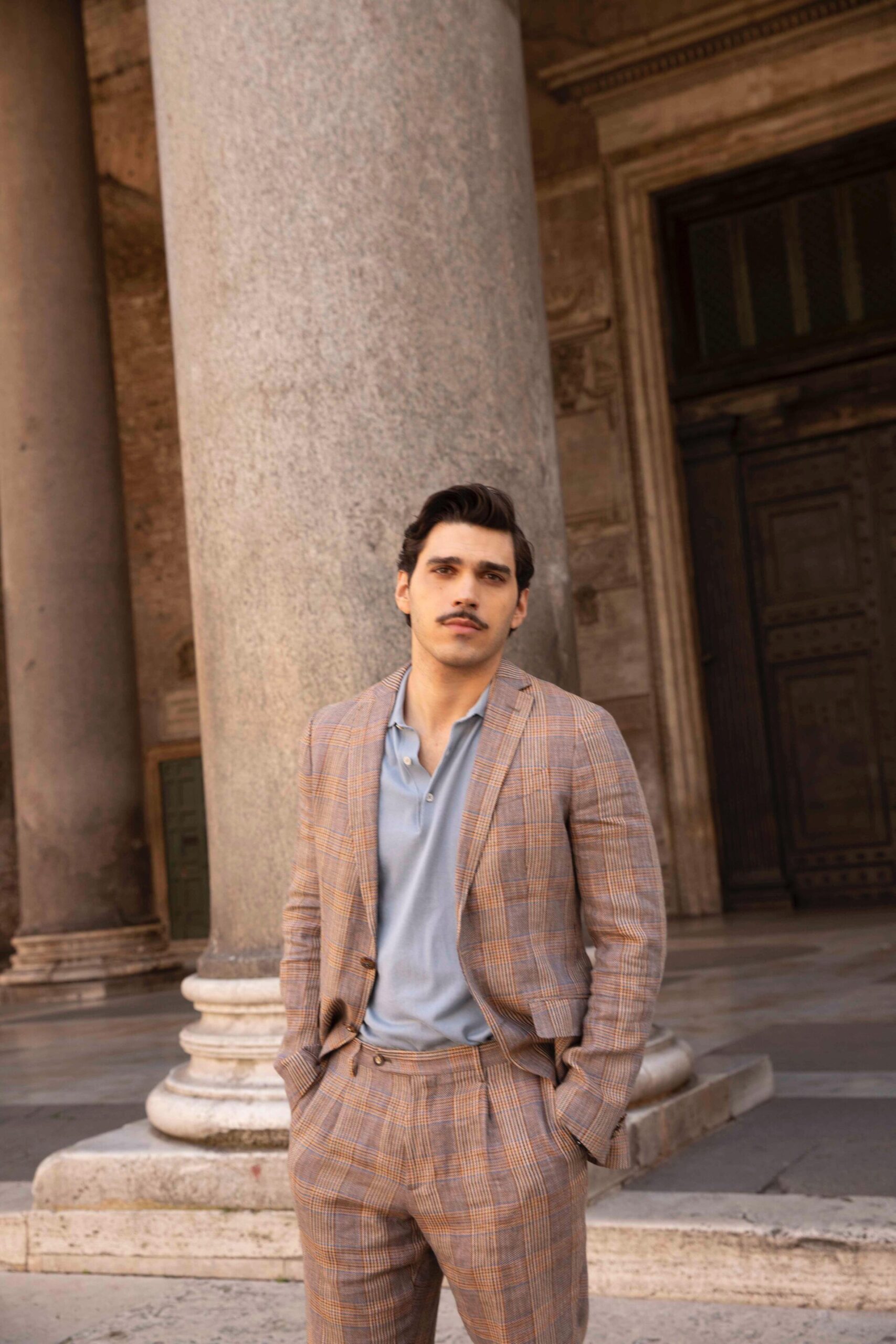

Photo courtesy of Victoria Dayan

Speaking of the past, there’s a Bertolucci quote: “Only those who lived before the revolution knew the sweetness of living.” That reminds me of a line from La mia ombra è tua: “Young people can’t afford nostalgia.” You were born in 1992—does that line ring true for you?

When Bertolucci wrote that line, it was the late ’60s—he hadn’t yet experienced the upheavals of the ’70s. He was talking about student revolts, about a society in flux. That line speaks to an enchantment lost to social struggle. Today, I’d reframe it: “Only those who lived through the First Republic knew the sweetness of living.” The ’70s and ’80s were years where anything seemed possible—the future held promise. Today’s global situation is more complicated, and young people are afraid to take risks. So yes, even I feel nostalgic for those times.

You’ve referenced that moment from Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, when after all the running, the fountains finally fall silent. Do you ever feel like you’ve reached that stillness—or are you still chasing something?

It’s hard to say. To truly stop, you have to stay in your comfort zone. But I’m always running from mine. That means I’m constantly facing bigger challenges. Still, if you find good relationships and have higher ambitions, you’re always in a state of motion, of electricity—there’s never real stasis or comfort. That’s especially true in acting. In other countries, acting is seen as sacred. In England, for instance, actors have a different social role than in Italy. Same in France, where the Comédie Française pays you just to be part of their system.

You’ve acted in France and Spain—you’re an international actor now.

You have to be, nowadays! That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t make films in Italy. It means we should also look to international markets. Take American cinema: to Americans, it’s still national cinema—even though it has global reach. Same goes for French films. It’s what Sorrentino is doing now in Italy. Our goal in cinema should be the same as our artistic forebears: when Fellini made a film, it was Italian, but also global.

When you do stop, where does it feel like home?

For me, home is people more than places—my parents, my wife, my family. Like here—[he shows his wedding ring]—I got married a year ago, right after Cannes. This is the first time I’m saying it publicly. I like to keep my private life private. My wife and my family are my safe harbor. As for places, Rome is part of me. Villa Borghese, for instance, is where I went as a kid and still walk today. I also love Paris, where they manage to highlight and protect all the beauty they have. Going back to that idea of the sweetness of living, I remember something my grandfather said before he died: “Well, at least we enjoyed it!” That’s what sweetness of living means to me—getting to the end and saying, “Well, at least we enjoyed it.”

This interview has been translated from Italian and edited for length and clarity.

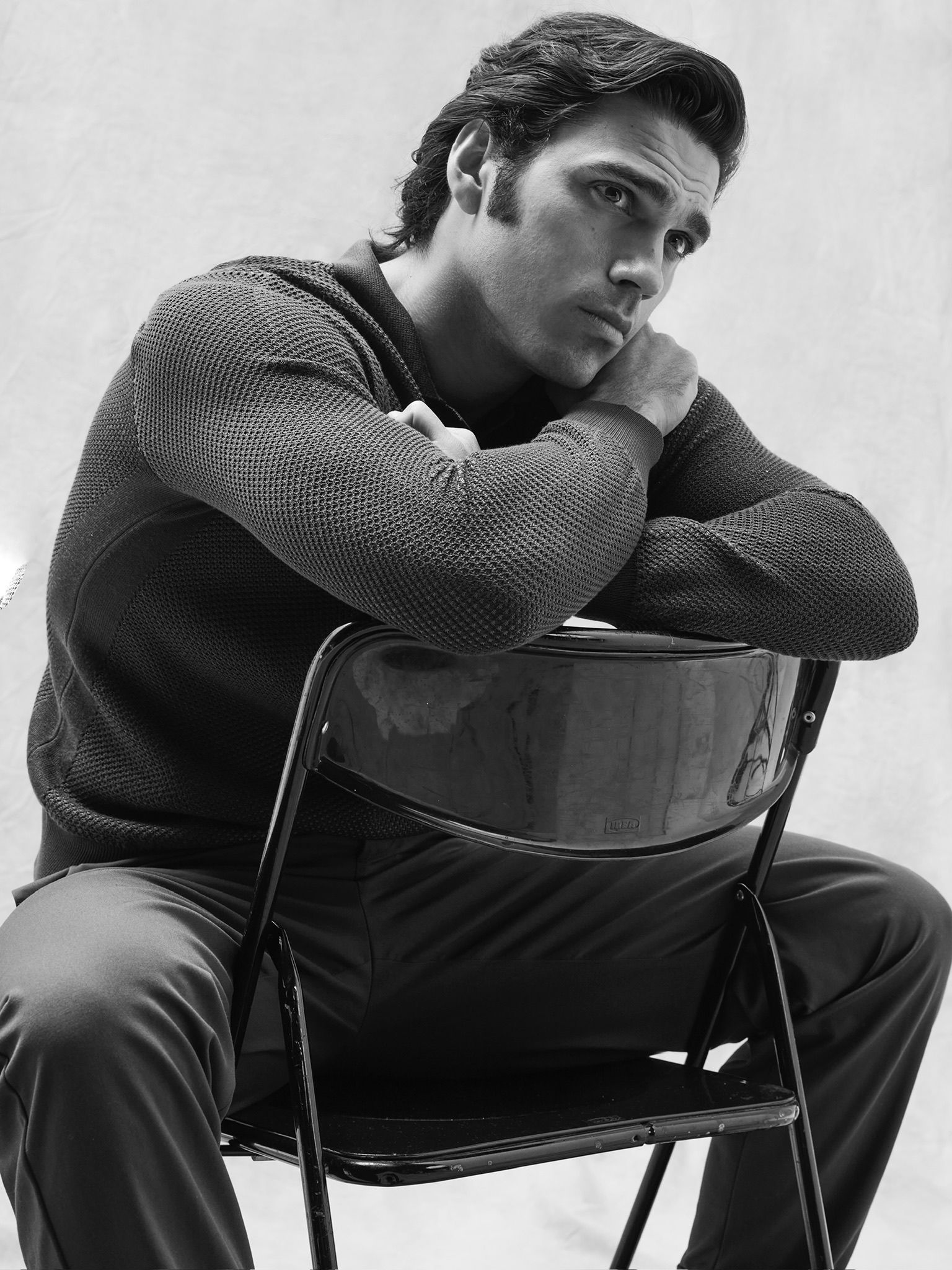

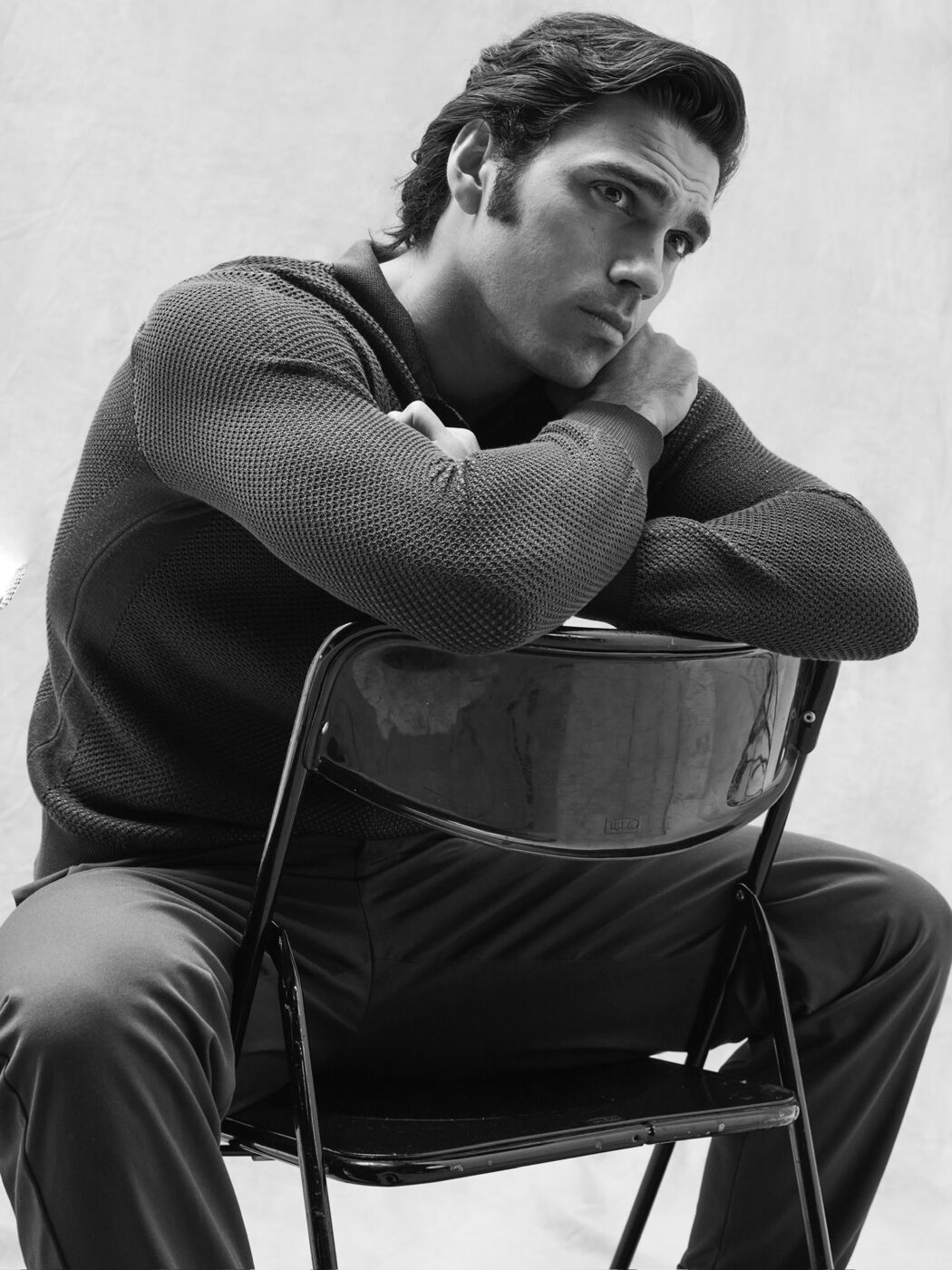

Maggio at home in Rome