Ancient Rome’s garum is back in the spotlight, thanks to Noma in Copenhagen. But in Cetara, a small town on the Amalfi Coast, it’s still made almost exactly as it was 2,000 years ago.

It may not sound particularly appetizing, but this ancient condiment—a fermented sauce made from salted fish innards—was once a staple across the Mediterranean. Today, its closest descendant is Cetara’s colatura di alici. Dark brown in color, intensely fishy in aroma, and so pungent in flavor that it’s used drop by drop, colatura is either considered a delicacy or ranked among the world’s most unpalatable foods, alongside Japanese natto or Icelandic fermented shark.

The tradition dates back thousands of years, to when salt and fish were among the most prized ingredients for Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans. Fish was difficult to catch and highly perishable, while salt was one of the few available methods of preservation. Garum was traditionally made by macerating fish innards and small fish like sardines and mackerel with spices, Mediterranean herbs, and salt for months—sometimes up to a year, depending on the climate—until it turned into a rich, savory sauce stored in small bottles as a prized seasoning.

This pungent condiment became ubiquitous in Roman cuisine as a seasoning in both the kitchen and at the dining table; a bottle of garum likely sat on virtually every table in the Empire, ready to be sprinkled over all manner of foods for a savory kick. As its popularity grew, garum production became a lucrative industry; coastal workshops from Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula) to North Africa produced the sauce in bulk for export, and the highest-quality batches commanded premium prices.

The Roman writer Apicius, who lived in the 1st century BCE, referenced garum as a condiment in about 20 dishes in his influential cookbook De re coquinaria. A century later, Pliny the Elder praised the garum produced in Carthagena, on the Mediterranean coast, where the Romans built specialized fish-processing facilities known as cetariae—the very origin of the name Cetara.

Cetara

Cetara is one of the villages along the Amalfi Coast—perhaps less postcard-perfect than others, and for that reason, still relatively untouched by mass tourism. Here, laundry flutters from balconies, children play in the streets, and fishing is still very much a way of life. The town is famous for its prized bluefin tuna and small, flavorful anchovies, which are still processed using traditional methods.

Cetara’s colatura di alici differs from its ancient predecessor. It’s a clear, amber-hued liquid with an intensely savory taste, made by maturing anchovies in salt. Traditionally homemade in Cetaran households, the process remains entirely manual: the anchovies are decapitated, gutted, and layered with salt in large oak barrels. Over time, they’re pressed, and after months of aging, the liquid is extracted from a small hole at the base of the barrel. Production begins in spring and continues through summer, when anchovies swim closer to shore and are easier to catch. The colatura is ready to be enjoyed around December—and that’s why the traditional dish for Christmas Eve in town is spaghetti with colatura. Simple, but tasty and a few decades ago a refined dish compared to the average diet. Pasta, boiled in non-salty water, garlic fried in olive oil, a bit of chili, chopped parsley, and a spoon of colatura to give a kick and saltiness.

Spaghetti with colatura

For years, this ancient tradition and its distinct flavor remained largely local, known beyond Italy only to a handful of devoted enthusiasts. But its fate changed thanks to a renewed culinary interest in fermentation—and a passionate ambassador: chef Pasquale Torrente.

A born and bred Cetarese, Pasquale Torrente grew up in what was then the family bar, opened in 1969 within a 17th-century cloister behind the town’s church—hence its name, Al Convento. Today, his trattoria is a must-visit for top chefs and lovers of great food alike, recognized as one of Italy’s best places to experience simple yet masterfully prepared traditional dishes, such as the aforementioned spaghetti. Pasquale has traveled the world introducing colatura di alici to new audiences and is a founding member of the Association for the Protection of Cetara’s Colatura di Alici, which secured its official Protected Designation of Origin (DOP) status in 2020.

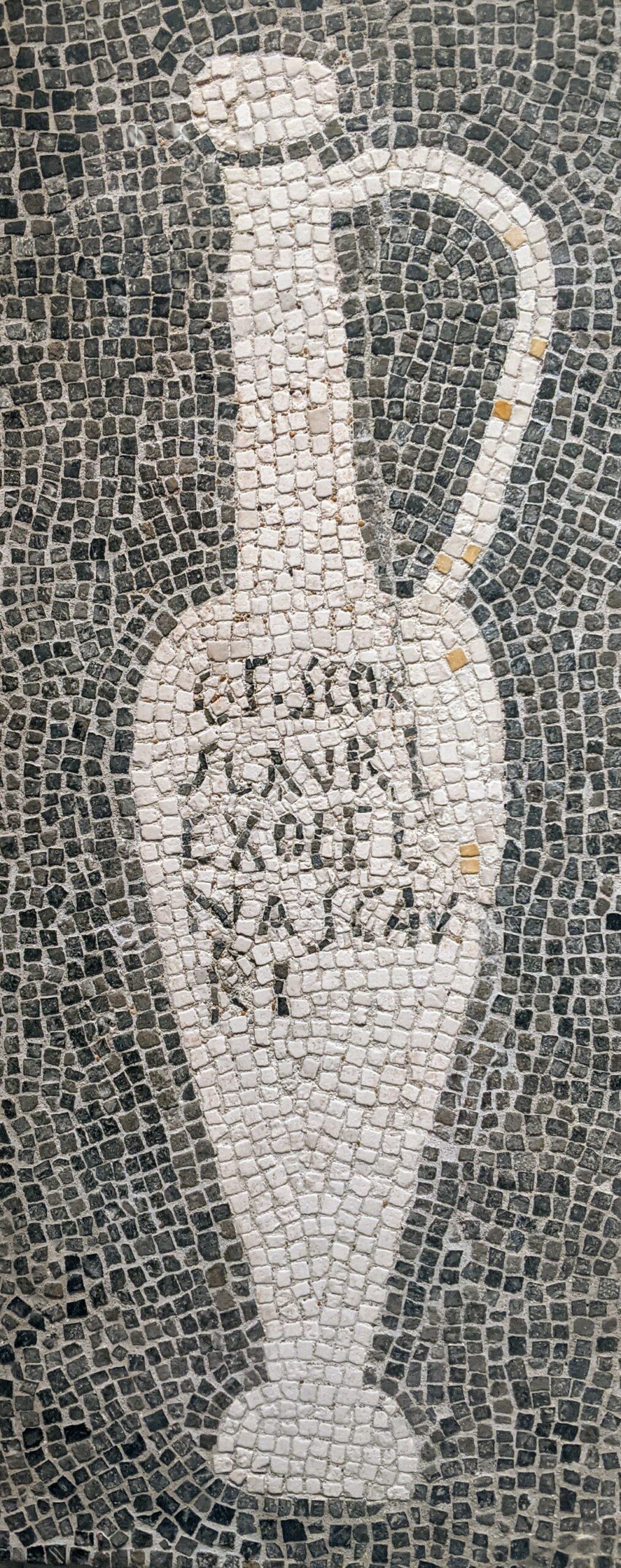

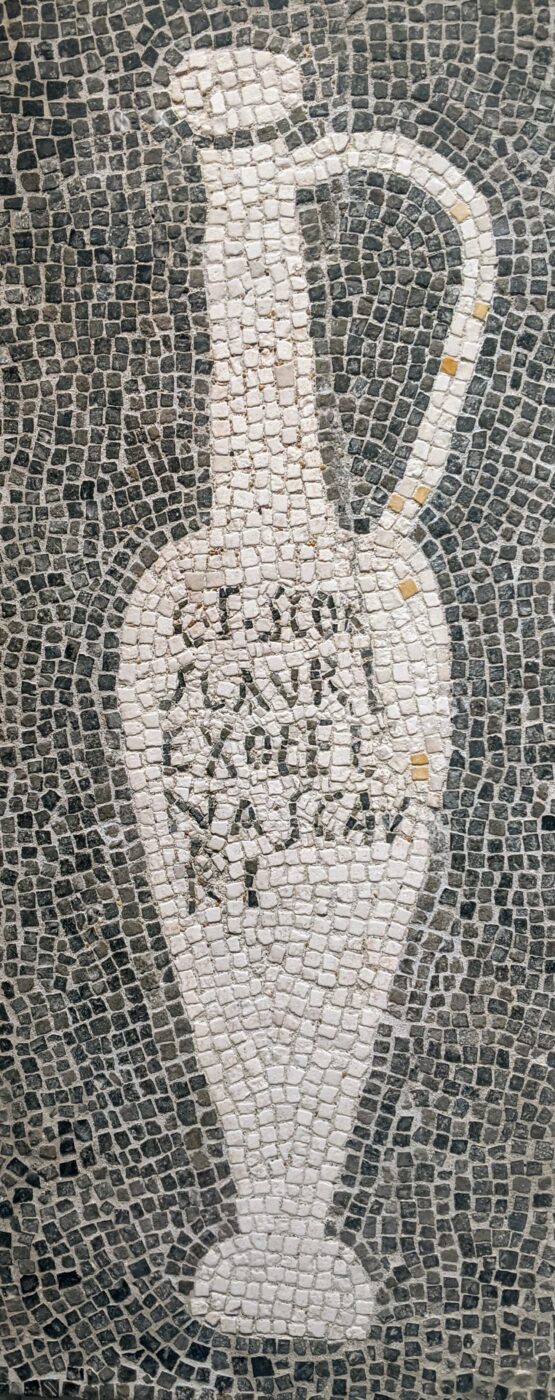

Pompeiian fresco: in the middle, a small amphora for garum; Photo by Chappsnet, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Torre di Cetara now houses a small museum dedicated to fishing and colatura di alici, showcasing artifacts and old photographs. But for those wanting to see colatura production firsthand, there is only one remaining business in town still making it the traditional, artisanal way: Fabbrica Nettuno. Despite its grand name, it’s more of a small, family-run workshop on one of the village’s narrow streets. If you visit at the right time of year, you might even be able to watch the process in action: a group of women chatting in the local dialect while expertly cleaning anchovies and layering them in small barrels, in what feels more like a home kitchen than a factory. Cetara and its colatura remain refreshingly authentic, a world apart from the hipster-driven revival of what many chefs now call garum.

Culinary terms rise and fall in popularity, and “garum” is currently having its moment—this time, thanks to René Redzepi of Noma in Copenhagen, repeatedly crowned the best restaurant in the world by The 50 Best Restaurants list. Redzepi sparked a global fascination with fermentation as a way to create deep, intense flavors while reducing food waste by repurposing scraps of vegetables, fish, or meat. His 2019 book Noma: A Guide to Fermentation became a must-have in professional kitchens worldwide, inspiring chefs everywhere to start fermenting—and calling their creations garum.

Noma's fermentation lab

After two decades of research and experimentation, Noma opened its fermentation lab to the public in 2021, launching a line of products used in its kitchen, including a highly umami-rich garum. A modern interpretation of the Roman condiment, Noma’s garum is vegan, made from mushrooms fermented for 6-8 weeks before bottling. It sold out almost immediately, prompting others to follow suit, such as chef Mattia Baroni, who introduced his re.Garum line, crafted from fish, meat, cheese, and vegetable scraps.

Today’s upscale garum bears little resemblance to the Roman original or to colatura di alici. Yet in its name, its fermentation, and its function as a potent condiment, it retains the essence of its origins: just a few drops are enough to transform a dish, adding depth to gourmet creations or oomph to vegetarian plates. Various versions of “garum” now appear on menus around the world, and restaurants bearing the name have opened in Modena, Naples, Minori, Mexico City, France, and London.

It seems that this ancient ingredient—or at least the allure of a distant past—has officially become a trend.