My grandfather was born one late winter in Coazze, a village nestled deep amidst the rolling hills of Piedmont. A dangerous February chill had crept into the family home and brought worry with it; his mother, heavily pregnant, was particularly vulnerable to the alpine cold. Her bed was moved into the barn, and she gave birth amongst the warmth and gentle bodies of the cows. A sort of Piedmontese nativity scene, my grandfather likes to say, and his eyes crinkle with characteristic mischief.

He tells this story not in Italian, but in French. Mussolini’s increasing hold over the nation had posed a threat, and just a few months after the “divine” birth, the family left the known embrace of Coazze in the hope of a new, better life in France. They are just one example of an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 Italian political refugees who left their country in the 1930s to flee the rise of Fascism.

France and Italy have a long, checkered political and cultural history. They share a border that has ebbed and flowed across the centuries; ownership over Mont Blanc, which straddles both countries, remains contested. Napoleon I governed much of Italy from 1796-1814, and France played a crucial role in the unification of Italy in the 1850s, offering financial support and aiding in the defeat of the Austrian Empire. Tensions became fraught in the late 19th century when the two nations competed over control of North Africa, culminating in France’s invasion of Tunisia. By World War I, however, Italy had joined the Allies, and both countries stood in solidarity as half of the Big Four.

Their historic relationship meant that immigration between the neighboring countries was by no means a novel phenomenon. However, by the late 18th century, the number of Italian immigrants had begun to rise, steadily increasing throughout the 19th century. Primarily, this immigration had been economically driven, though it was bolstered by a wave of political immigration following the end of World War I, as the threat of Mussolini’s Italy loomed. Most of the Italians seeking refuge in France were from Northern Italy, largely originating from Piedmont and Veneto, whose advantageous positioning closer to the border facilitated their migration.

The influx was vast: by 1931, there were over 800,000 Italians in France. My great-grandfather was one of them; he smuggled himself into the country by train, trundling through the Mont Cenis tunnel across the snow-capped Alps to reach Modane, a French border town with a swelling Italian community.

Italians, however, were not what he had been looking for. “We are in France now,” he said to his family, who had followed him across the mountainous border. “We need to speak French, and we need to become French.” They moved swiftly away from Modane to a small village above Lyon, where just one other Italian resided. This was an unusual decision–most Italian immigrants at the time wanted to stick together. And yet, “we’ll never integrate if we live with other Italians,” my great-grandfather had pointed out, and knuckled down on his journey to assimilation.

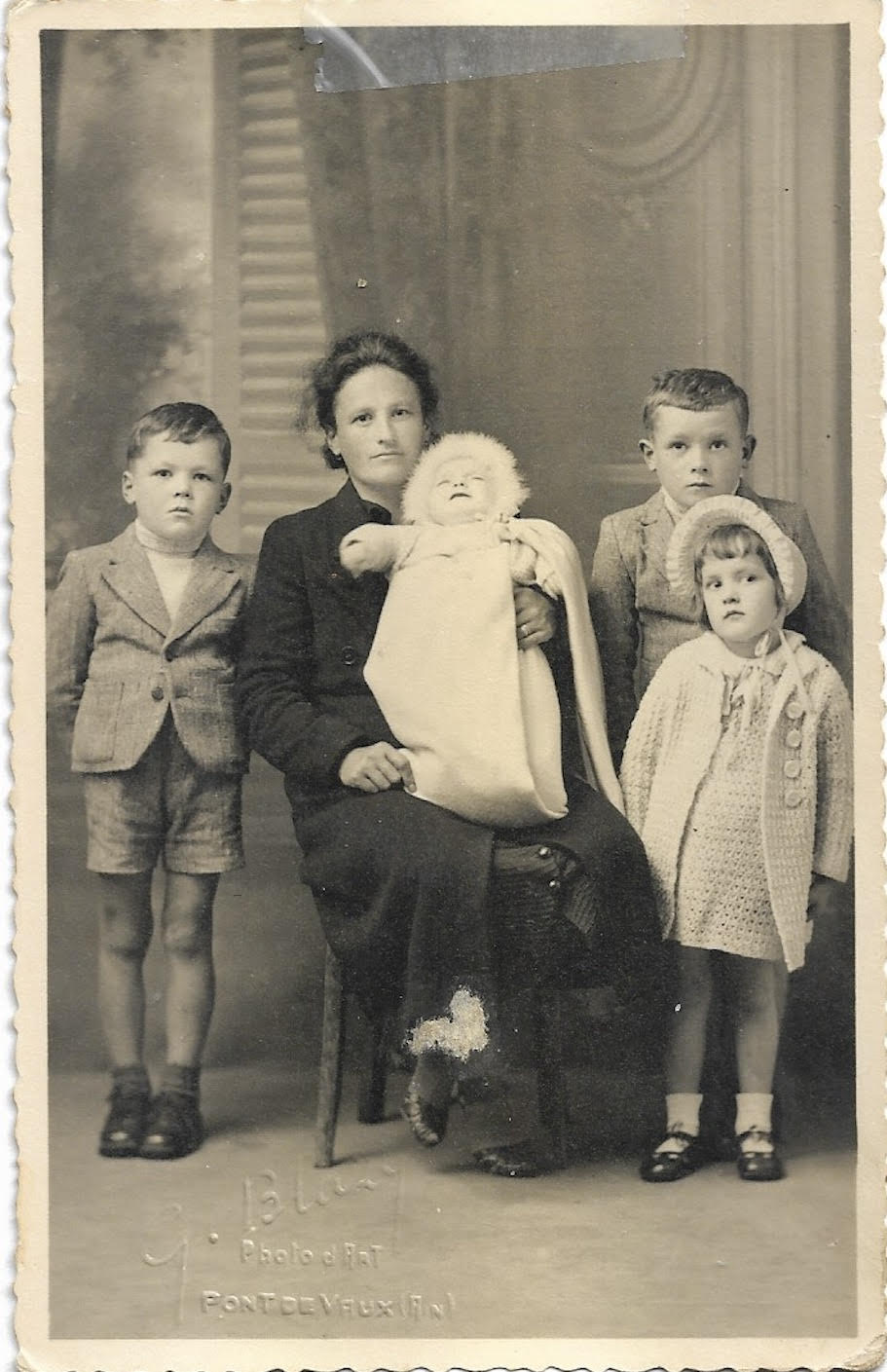

Severin and his two aunts

The divorce from their home country and whole-hearted embrace of their new one flooded into every cranny of their life. Italian was banished from the family home, and the parents spoke only French to the children, whilst still grappling with the language for themselves. My great-grandfather took his adopted French-ness seriously; later in life, sorry were those who dared to interrupt when he was watching Charles de Gaulle give a speech on television.

Yet fragments of Italy snagged and remained. Meals of chestnuts and white cheese were punctuated by warm, golden bowls of polenta, a northern Italian staple that had too made its way across the border. Between each other, the parents spoke dialetto, and sometimes, my great-grandmother would sing it. Home alone while her husband worked long hours and with five children to look after, the move away from a safety net of family and friends had not been easy. My grandfather still talks about her voice, which would curl and rise through the house, crooned snatches of a home left behind.

My great-grandfather’s urgent desire to assimilate reveals a wider, darker reality lived by Italian immigrants in France. The derogatory term “Rital” was coined to refer to Italian immigrant workers, and rapidly mutated to become an insulting label for any Italian, specifics of their living situation aside. The word was taken from the documents that were carried by Italian immigrants who arrived in France, Belgium, and Switzerland at the start of the 20th century. “R. ital.” was stamped at the top, “Réfugié Italian.”

Claude Barzotti’s famous song “Le Rital” is sung from his perspective as a second-generation Italian immigrant. “À l’école quand j’étais petit/Je n’avais pas beaucoup d’amis/ J’aurais voulu m’appeller Dupond/Avoir les yeux un peu plus clairs/Je rêvais d’être un enfant blond”, he sings (“At school when I was little/I didn’t have many friends/I would have liked to be called Dupond/ To have slightly lighter eyes/I dreamed of being a blond child”). “C’est vrai, je suis un étranger”, he goes on, “on me l’a assez répété…” (“It’s true, I am a foreigner/I’ve been told enough”).

The popularity of Barzotti’s song softened the pejorative quality of “Rital”, with the singer reclaiming the label and wearing it with pride. Yet his lyrics are revealing of a pertinent anti-Italianism that had been brewing in France as the number of Italian immigrants rose. By no means limited to school-time bullying, cases of xenophobia manifested themselves in the extreme: just a few decades prior to my family’s move to France, a number of immigrant Italian workers were killed by French villagers in an incident known as the Massacre of the Italians at Aigues-Mortes. The exact figures are contested, with the number of deaths ranging from 17 to 50, and the number of injured from 150 to over 400. The massacre was one of a series of attacks on Italian immigrants, who were happy to work for less, thus resented by French laborers competing for the same jobs. The challenges faced by Italian immigrants led to a phenomenon known in France as la migration de retour, or “the return migration”. Of the near 27 million Italians who left Italy for France after the unification and throughout the 20th century, over half returned. (Today, there are approximately 5.5 million French nationals of Italian origin.)

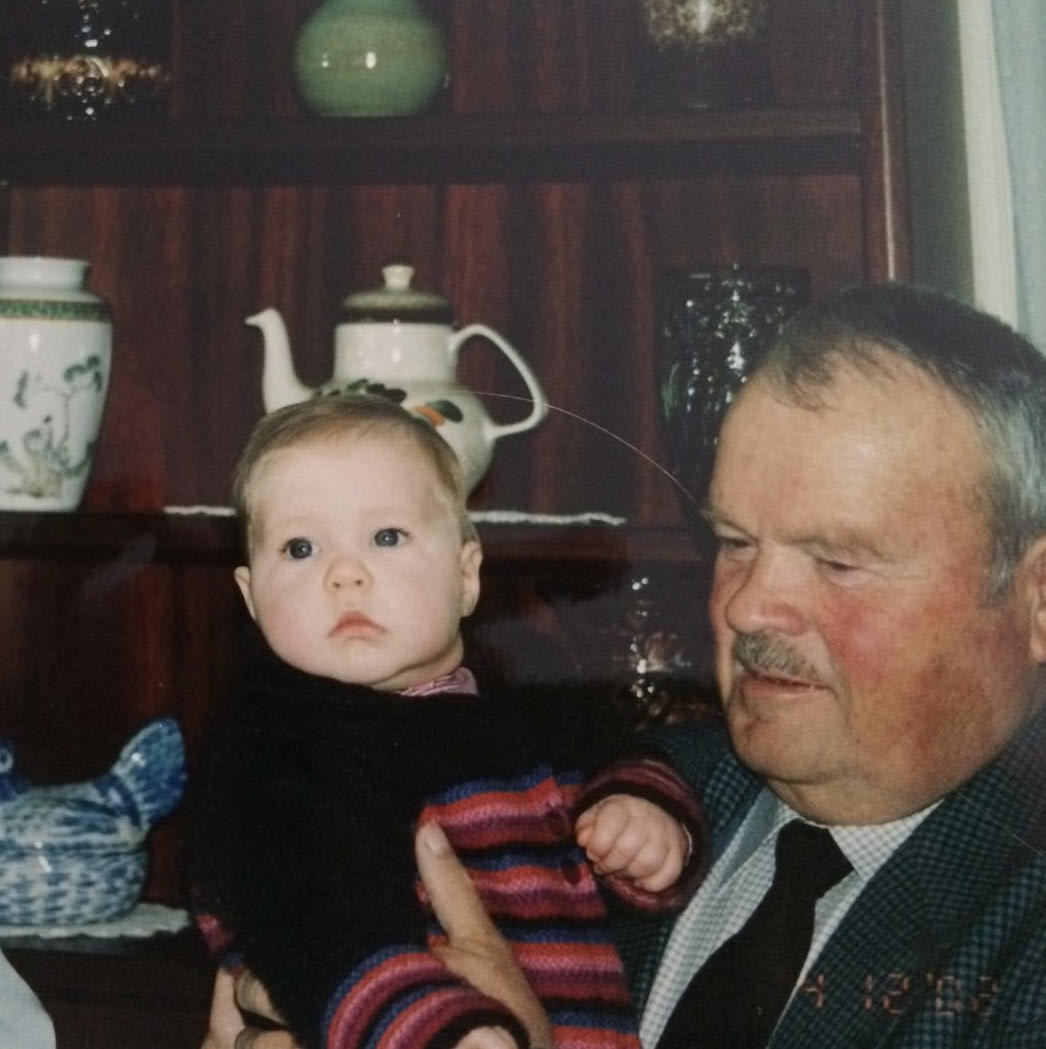

Author Clementine Lussiana and her grandfather

My grandfather, however, insists that they were warmly welcomed. Perhaps things were different for an Italian family who spoke French and kept away from their own. Despite this, uneasy anecdotes emerge: stories of dangerous jobs and refused pay. My grandmother, French to the bone, got engaged to my grandfather after they met at a village dance, where he had precisely enough money to buy them two entry tickets and one lemonade. “Couldn’t she have done better than an Italian?” frowned a cousin. “Weren’t there enough French men to choose from?” remarked the owner of her local restaurant.

My grandfather maintains that hostility was and still is rare, but the isolated incidents highlight a curious history between the two countries that are at once old friends and old enemies. It was Jean Cocteau who called the Italians “the French with a smile”, and so perhaps my grandfather’s unwavering chirpiness about the challenges of being a foreigner in France suggests that part of that village in Piedmont remains somewhere rooted inside him; how despite it all, a distinctly Italian sense of humor and appetite for food and life remain.

My grandfather was born Severino, but is known by the gallicized Severin, and his seemingly native Frenchness to anyone who meets him proves that the assimilation his father fought so hard for has come to fruition. In two generations, the family had become French, my father and his two brothers raised without even a whisper of alpine dialetto. My father tells me he feels French, not Italian, though he was still teased as a “Rital” at school, a softened insult at that stage that nevertheless reminded him of the foreignness of his surname. As for me, granddaughter of an Italian raised in France, my blood connection to Italy feels so tenuous that I think of myself as an Italophile more than anything else. And yet, who knows? Perhaps my desire to learn Italian came from a subconscious, romantic calling to understand who my family had been once upon a time, and who we might have been had they stayed.

My great-grandmother died prematurely of cancer. Muddled by the morphine that was helping her fade away painlessly, she was convinced she would recover. “I’ll get better,” she used to repeat to herself, lying on a bed not in a barn in Piedmont, but in her room in Sermoyer, France. “I’ll get better, and I’ll be able to go and rest in Italy.”