In April of 1254, a widow in Genova gives her house to the monastery of San Pietro di Prà for an intriguing sum: 50 lire of Genovese money and an annual supply of a certain amount of “casei paramensis,” otherwise known as “formaggio parmigiano.”

For those of us whose idea of Italy is inextricably intertwined with Parmigiano Reggiano, which may in fact be all of us, it seems unthinkable that there was ever a time when the sharp, crumbly kitchen staple didn’t exist. But this Medieval deed is actually the “first documented reference” of the cheese, per research sponsored by the Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigiano Reggiano, the body that “protects and defends” the cheese’s Denominazione d’Origine Protetta, or Protected Origin Designation.

Even then, the nutty taste, its perfect pairing with pasta, was the stuff of fables–literally. In Boccaccio’s Decameron, Parmigiano has a role in the story of Bengodi, a so-called dream land in which all is meant to be enjoyed. “And on a mountain, all of grated Parmesan cheese, dwell folk that do nought else but make macaroni and ravioli, and boil them in capon’s broth, and then throw them down to be scrambled for,” the story recounted on the eighth day. Suffice it to say that Boccaccio was writing in the mid-14th century, but mountains of grated Parmigiano–and, truthfully, I would take ungrated–may still rank in our idea of paradise.

That’s not just supported by my personal craving, but by the global market, which continues to exhibit a high demand for this traditional Italian product. In 2023, total Parmigiano Reggiano sales worldwide reached more than three billion euros, up from 2.9 billion the previous year. Sales in Italy went up by 10.9% year-over-year. Contrast this with production: in 2023, 4.014 million wheels of Parmigiano were produced in Italy, a miniscule increase from 4.002 million the year before. Unsurprisingly, Parma was the largest producer of the cheese, with Reggio Emilia a close second.

The Consorzio has made a concerted effort in recent years to push Parmigiano to foreign consumers, including an investment of €31.8 million towards marketing in 2023; of external buyers, the United States is the top market. Still, the Italian market makes up the largest share of Parmigiano buyers, representing about 57% of the cheese’s total sales in 2023. And things are becoming ever more close to home–direct sales from cheese factories actually went up by almost 11% year-over-year.

“2023 was a year of great challenges for Parmigiano Reggiano, but it ended with positive results, with sales up by 8.4% and exports up by 5.7%,” said the Consorzio’s president, Nicola Bertinelli, at a March 2024 press conference. “In the near future, the Consortium will increasingly need to invest in the growth of foreign markets, which represent the future of our PDO.”

But as Bertinelli’s comment implies, Parmigiano Reggiano has weathered its fair share of obstacles, both as it relates to the production and the sale of the product itself. The famous Italian cheese has the designation DOP or denominazione d’origine protetta, given to products regulated by the European Union for their geographic heritage. But in recent years, these have been threatened by so-called “counterfeit” items sold in other countries that bear similar verbiage but are not actually made to the standards laid out by the DOP. Fake Italian products, for example, had reached a value of roughly €120 billion by May 2023, per leaders from Coldiretti, Italy’s main farm union. At that time, Coldiretti reported that more than two-thirds of Italian products around the world were considered fake and with no connection to Italy.

In 2019, the sale of “fake” Parmigiano and Grana Padano had actually surpassed that of the real versions, per Coldiretti data. That year, the United States produced roughly 204 million kilograms of “parmesan.” Only about one percent of Italian cheese purchased in the U.S. had any link with products actually made in Italy.

“The pretense of calling profoundly different products by the same name is unacceptable and deceives consumers and poses an unfair competition to business owners,” said Coldiretti president Ettore Prandini in a 2019 press release.

At the same time, Parmigiano has faced threats from the very landscape that has given the trademark product its DOP status. In 2022, northern Italy’s River Po hit record low levels, according to CNN reporting, during the area’s worst drought in more than 70 years. CNN reporters talked to local dairy farmers, like Mantova’s Simone Minelli, who worried that the lack of water would leave him unable to feed his 300 Friesian cows, which need 100 to 150 liters of water a day. Water from the Po is also used to irrigate the crops, like soybeans, that serve as feed for the cattle.

“I’m very worried; we take it day by day,” Minelli told CNN’s Barbie Latza Nadeau and Livia Borghese at the time. “If you don’t have enough food to feed your cattle, you have to reduce.”

Courtesy of Parmigiano Reggiano

The History of Parmigiano

There’s a reason Boccaccio named Parmigiano in the Decameron–that’s how characteristic of the region the cheese already was. The cheese’s production started in the Middle Ages, according to the Consorzio, with Benedictine and Cistercian monks who combined the salt from Salsomaggiore salt mines, located in the province of Parma near the Apennine Mountains, with milk from the cows of their monasteries. The original goal of Parmigiano was to create cheese that could be preserved for long periods of time.

But by the 15th century, the production had spread to non-religious structures and the plains of Parma and Reggio Emilia. The wheel size of Parmigiano went up to 18 kilograms, roughly half of the size they are today.

In 1612, we find the first inklings of DOP in a legal document from the Duke of Parma’s notary, in which it is stated that only the cheese made in Parma and its surrounding cities can be conferred with the name Parmigiano. Even if cheese from Fontanazza and towns like Piacentino “have been often taken to be preserved in the cassine of Fontevivo,” they still, however, had to be negotiated and sold with the name Piacentino cheese, per Parma’s Museo del Parmigiano Reggiano.

Still, it took more than 300 years, in 1934, to decree a more official version of what would become denominazione d’origine protetta. It is then that representatives from dairy farms of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, and Mantova joined together to form the Consorzio Volontaria Interprovinciale Grana Tipico, giving the brand its name: Parmigiano Reggiano.

In modern times, DOP means that each Parmigiano must uphold certain standards: for example, a minimum of 75% of the cow feed must come from the DOP area. The ingredients must be only cow’s milk, salt, and rennet, and the milk must be from cows in the geographical area, which is defined as Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna to the left of the river Reno, and Mantova to the right of the river Po.

The Parmigiano Process

At the Ciaolatte cheese factory in Noceto, just outside of Parma proper, an intimate yet industrial scene emerges, that of circular copper vats filled almost to the brim with a milky substance. This would be, unsurprisingly, milk, whey starter, and rennet, enzymes taken from the stomach of cows. The milk is divided between the evening milking, taken from the cows at noon the day before, and one from that very morning. The cheese is made only once a day and requires roughly 550 liters of milk for each wheel of cheese weighing in at around 36 to 40 kilograms.

The texture is first tested with a hand and then stirred with a metal instrument, known as a spino in Italian, resembling a large honeycomb. Slowly, slowly, the ingredients come together to form a solidified substance, rivulets of what will become Parmigiano coming to the surface, almost like a rice pudding. The copper of the vat serves as both a heat conductor and an oxidizing agent, explaining its traditional use in cheesemaking. The cheese-master, who is the head of this entire operation, comes to each vat after about 50 minutes to ensure that the cheese is ready.

From the underbelly of the vats, the now almost mozzarella-white cheese emerges from the yellow liquid and is contained by a cheese-cloth, which is tied to a wooden plank that lies perched on either end of the copper vat. From this mass of hanging cheese, the cheese-master slices with what looks like a miniature saw.

“The twins are born now,” declares Ilaria Bertinelli, who hails from a family of cheese-makers and is an official guide for the Consorzio as well as the sister of its president, as we watch the process. She is, of course, referring to the twin wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano that will emerge from this vat.

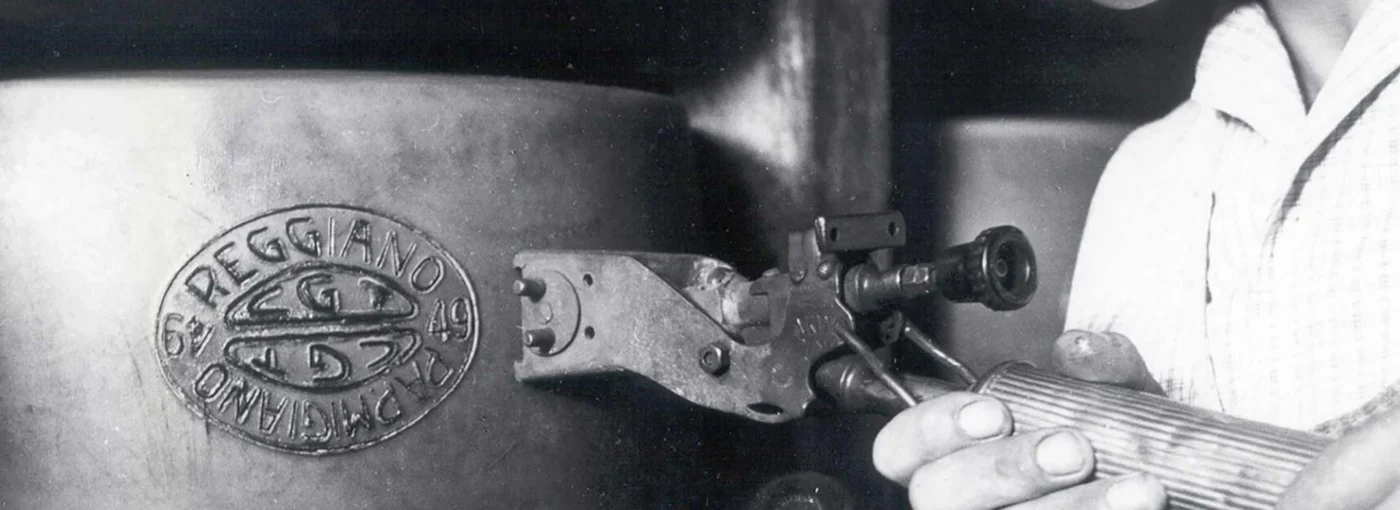

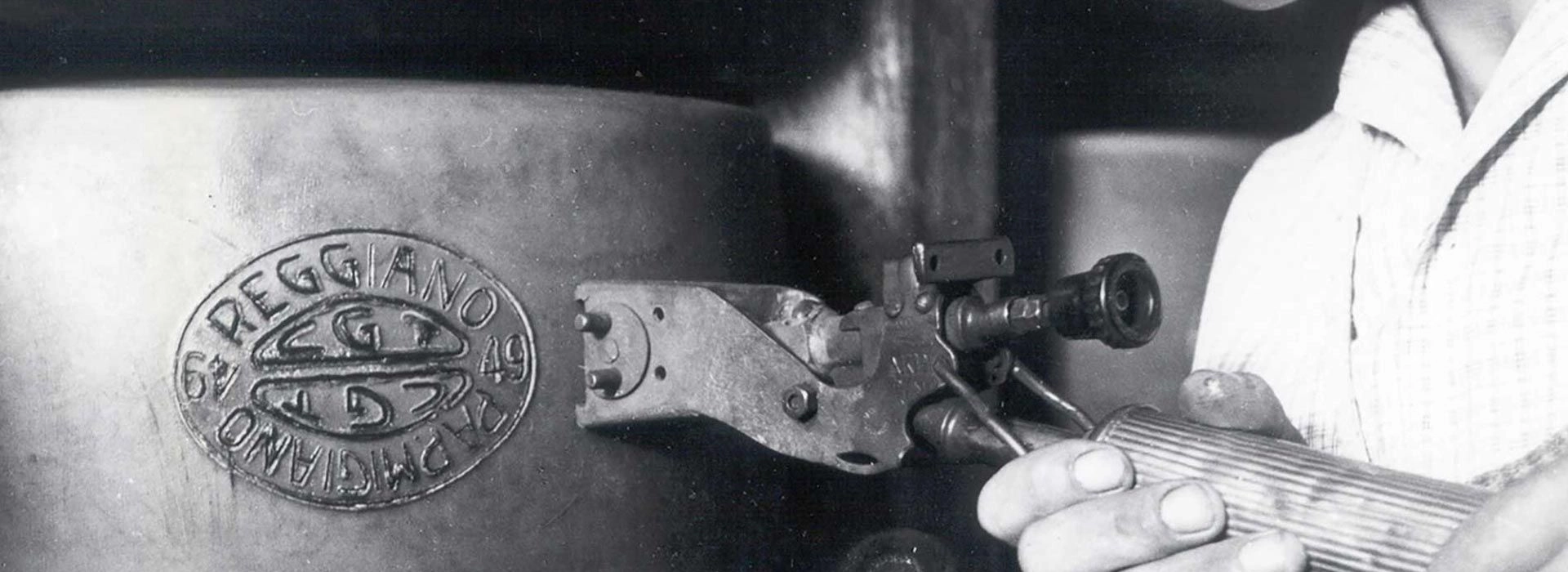

The cheese is then left to sit for 19 days in a bath of brine, which acts as a salt and water extractor. The Parmigiano, Bertinelli notes, actually loses four percent of its weight by the end of its soak. Once taken out, it stays in a warm room for a couple of hours to be dried before being carried into the maturation rooms, which are reminiscent of wine cellars, with stacks and stacks of Parmigiano wheels shelved one on top of another. Here are cheeses aged 18 months, 24 months, even up to 40 months. The seemingly endless shelves of Parmigiano, punctuated by rays of light from a window at the back end of each aisle, are a testament to the longevity of the cheese itself. Each wheel is stamped with the month and year of its production and its own unique alphanumeric code–in theory, it can be tracked all over the world.

“These are the true cathedrals of Parma,” Bertinelli says, “because they are like the banks–they have our wealth.”

On a wall of the Ciaolatte caseificio sits a poster with a sepia-toned photo of Parmigiano Reggiano on a tagliere, next to a heaping plate of spaghetti piled high with Parmigiano, a cheese-grater, a fork, two tomatoes. A modern-day Italian natura morta, if there ever was one–the ad reads: “Vuoi mettere…è parmigiano reggiano! Vuoi mettere…che spaghetti!” (“When it’s Parmigiano Reggiano, the spaghetti turns out!”) In tiny script underneath the cheese’s logo is a tagline: “Qualità e genuinità fanno la differenza.” Quality and authenticity make a difference.