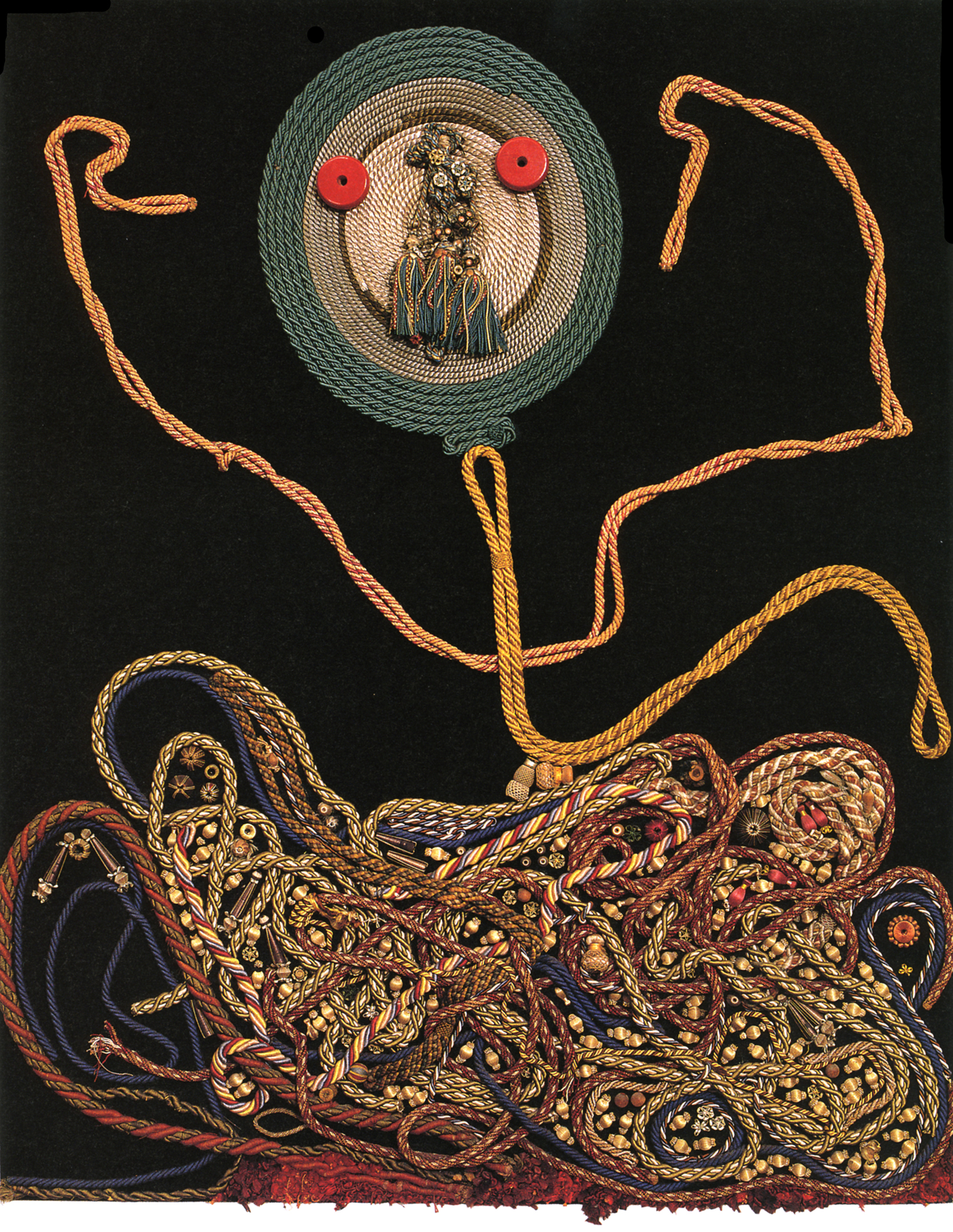

Thread reels, glass chips mounted on pieces of metal, cut-outs, medals, buttons overlapping with ribbons, trinkets and trimmings, offcuts, sequins, rosettes, laces, bits of every kind rearranged in the shapes of eyes, noses, or ears. These are the pieces that make up the cast of characters born by Enrico Baj, whose surrealist and sci-fi universe wielded irony and the grotesque as tools to dismantle bourgeois conformity–and challenge any form of established power, really. It was a universe that could have only been a product of a certain time and place: mid-century Milan.

"Berenice" by Baj (1960); Copyright 2015 © ARMELLIN F.

Looking at the surface of the painter and sculptor’s works–textured, almost sculptural–makes you want to stroll around Milan’s mercerie, those haberdashery shops with old-fashioned fonts and walls plastered with button boxes. Inexplicably still in business today, these botteghe storiche were once the epicenters of the city’s affluence and vanity–ripe inspiration for the anarchist artist, who ridiculed the bourgeois need for self-validation and demand for embellishment that he’d grown up around.

Born in 1924 to a well-off Milanese family (it takes one to know one!), Baj lived an uber-Milanese life. He studied at renowned institutions in the city, starting with Liceo Berchet and moving on to the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera, the heart of the art scene. His first solo show, in 1951, was held at Galleria San Fedele, then just two-years-old and now one of the city’s historical galleries. From the mid 1960s, he exhibited regularly at Studio Marconi, arguably Milan’s greatest exhibition space in those years, and would go on to become one of the most frequently featured and beloved artists of his friend and gallerist Giorgio Marconi.

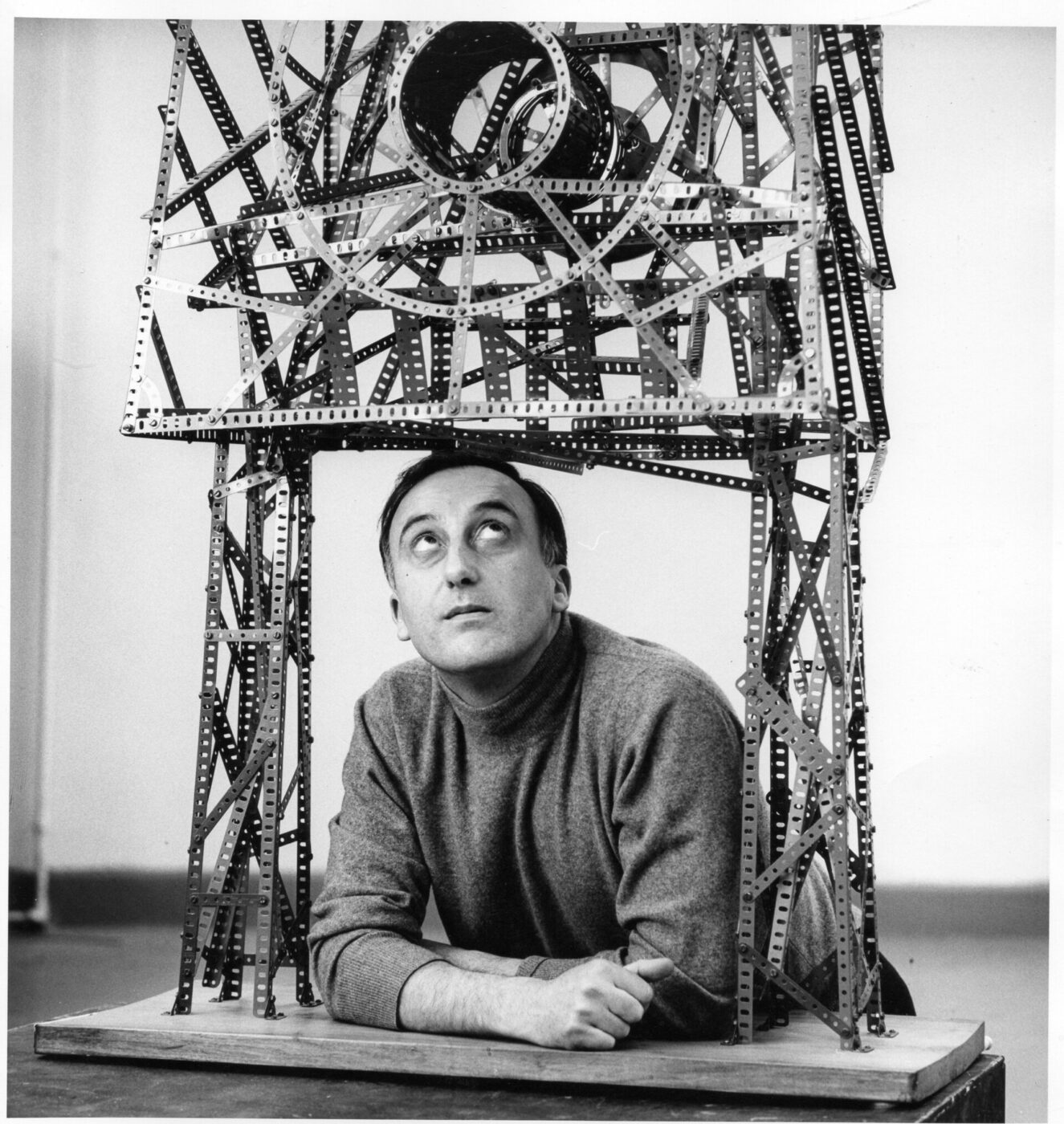

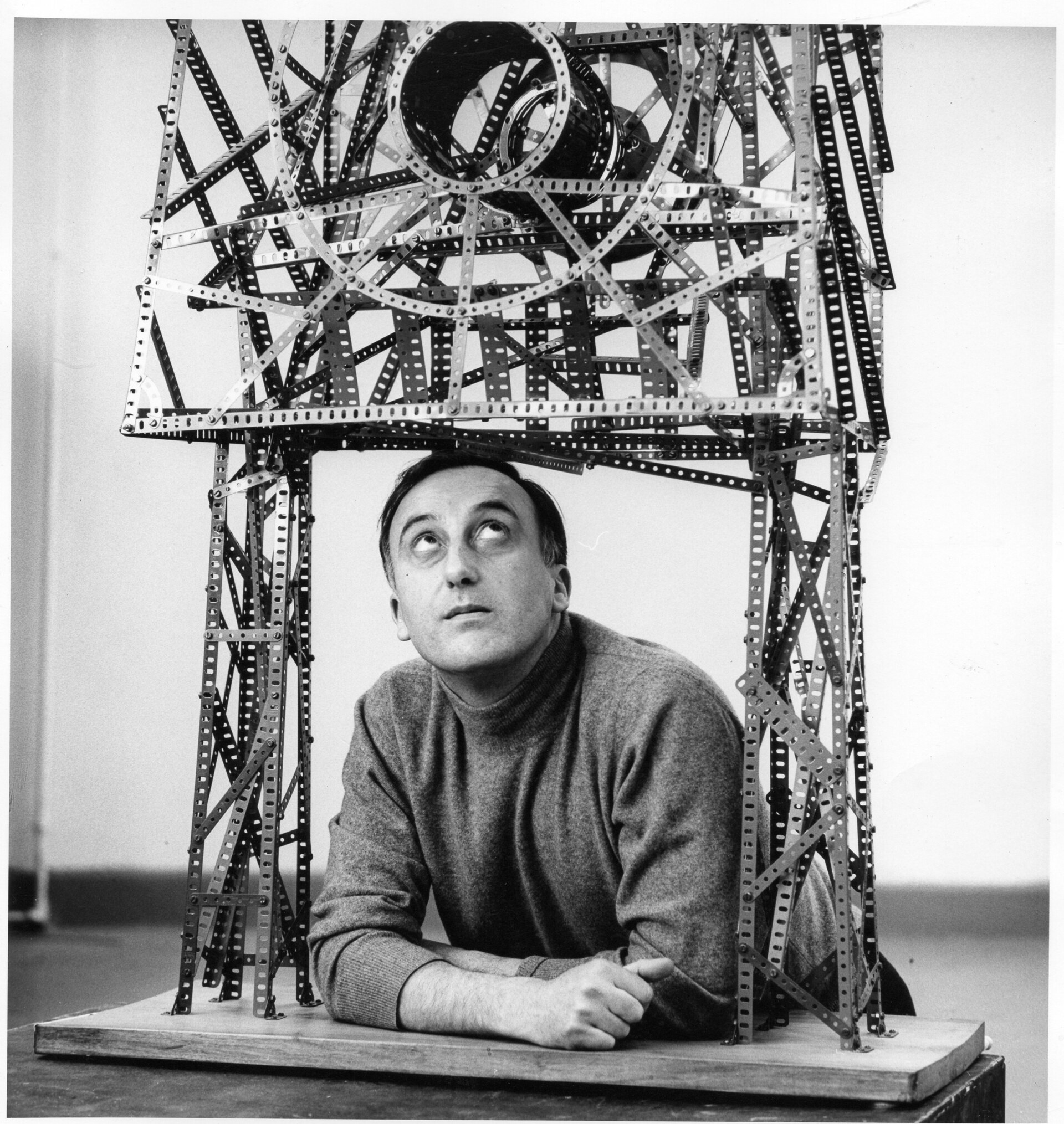

Enrico Baj, 1964

Living in Milan also meant getting exposure to cultural influences from beyond the Alps, Paris in particular: André Breton, the father of French Surrealism; Marcel Duchamp, the Dada idol; Raymond Queneau, and Asger Jorn all left their mark on the Italian. A master in recycling, Baj would reclaim whatever came his way, including artistic movements. The Milanese re-interpreted key movements and artists, including Futurism and Metaphysical painting, to suit his own critical and satirical vision. One of his most famous works, La vendetta della Gioconda (The Revenge of the Mona Lisa, 1965) is grotesquely playful and intentionally distorted, replacing the demure features of da Vinci’s original with something far more chaotic: the bespectacled visage of Duchamp, who himself had already defaced the Mona Lisa with a mustache in L.H.O.O.Q. (1919).

Another of his most renowned works, the monumental, mixed-media installation The Funeral of Anarchist Pinelli (1972), which covers an entire wall and spills over onto the floor, makes reference to a Futurist painting by Carlo Carrà. The result of three years’ work, this twelve-meter-long piece was inspired by the death of political activist Pino Pinelli, who suspiciously fell from a window while in police custody at Milan Police Headquarters in 1969. He had been held as a suspect in the Piazza Fontana bombing, a terrorist attack that killed 17 and wounded 88 and was initially blamed on anarchists but later found to be the work of neofascist groups. To allude to Carrà and Futurism, whose authoritarian tendencies had aligned the artistic movement with fascism, was to flip their ideals on their heads, to point to the dangers of blind nationalism, militarism, and the fetishization of technology. These were themes that swirled around Italy during these so-called “anni di piombo” (“years of lead”)–particularly in Milan, a hotspot of political activity from both ends of the spectrum–and that informed much of his work.

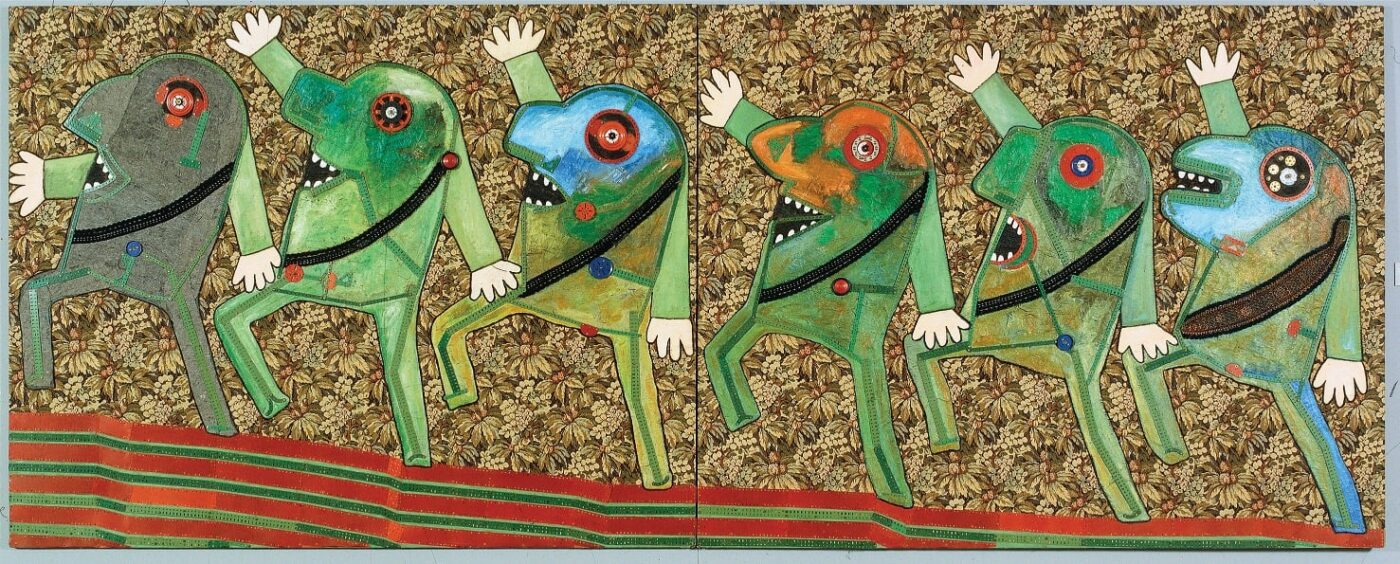

A fascination about and repulsion for the looming threat of nuclear war during the tormented political period of his lifetime led Baj to co-found the Nuclear Art Movement in 1951–with quite the ambitious program: “The Nuclear Artists want and can re-invent Painting. Shapes disintegrate: the new shape of humankind are those of the atomic universe.” An artistic response to the existential anxiety of the post-World War II era, the movement, with nightmarish figures and grotesque compositions, reflected the unpredictability of a world that had experienced the destructive power of nuclear weapons. A shrewd critic of contemporaneity, Baj’s nuclear work addressed society’s obsession with technology with legions of robots and dummies, while his deformed Generals mocked authoritarianism and masculine pride. The latter series–depicting military personnel with exaggerated features and pompous, bemedaled chests–read as caricatures of the fragility of power.

"Parata a sei" by Baj (1964)

"Generale" by Baj (1961); Photo by Gianni Ummarino

The Milanese neighborhood of Brera was fertile ground for these Nuclear artists–as it was for most of the city’s avant-garde movements of the moment. They’d meet at the quintessential Bar Jamaica over a coffee or a cocktail, or at the now-defunct Santa Tecla jazz club, which Baj and his contemporaries Joe Colombo and Sergio Dangelo once decorated with a montage of disintegrated posters and suspended mannequins dangling from the ceiling. Milan’s historic establishments were the perfect backdrops for the artists’ cultural initiatives; they often invited physicists and scientists to present alongside their works, fostering collaborations that pushed the boundaries of both art and science. These were the years when artists were still signing manifestos and grooved on belonging to movements both political and artistic. Baj enjoyed his own so much that he even sued his colleague Salvador Dalì over a dispute for plagiarism when the surrealist claimed to be the “inventor of nuclear painting”; Baj secured a preliminary ruling in his favor from the Milan Justice Court in 1954, mostly because the Spanish artist couldn’t be bothered to show up.

But even the artist’s rebellious, anarchist spirit couldn’t hold against his bourgeois Milanese roots. At the end of the 1960s, Baj and his wife moved into an Art Nouveau villa in Vergiate, a bucolic town in the foothills of the Italian Alps. The house, which suited the best upper-class habits, was conveniently close to both the lakes and the city and became the center of the couple’s life until Baj died in 2003. Its maximalist interiors feature works by André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Gerhard Richter, and Joe Colombo, hung salon-style, together with dozens of Baj’s own paintings and works on paper, among 19th-century sofas and rigorously antique furniture: Baj, ever the provocateur, had a deep disdain for modern design.

"BAJ chez BAJ" at Palazzo Reale; Photo by Lorenzo Palmieri

Recently, a retrospective at Milan’s Palazzo Reale, “BAJ chez BAJ”, celebrated the artist’s 100th birthday. Curated by Chiara Gatti and Roberta Cerini Baj, the artist’s widow and depositary of Baj’s legacy, the exhibition featured almost 50 works from the early 1950s to the dawn of the 2000s, including the much-discussed The Funeral of Anarchist Pinelli, twelve years after it was exhibited in the same room. To walk through Palazzo Reale during these days is to enter into another dimension, one in which generals stick their bulbous noses in the air at you, in which Pinelli’s mourners claw the air, in which grotesque characters stare, blank eyed, into your very depths. It’s a dimension in which chaotic forms dismantle everything you knew of conformity, leaving only a kaleidoscopic anarchy of imagination.

“A light-hearted anarchist”–so the exhibition catalog described the artist. I’d throw “Milanese” in there too.