Thirty-seven-year-old Alessandro Cannavacciuolo grew up in the so-called Terra dei Fuochi, a wide swath of land between Naples and Caserta that has been home for decades to the illegal dumping of toxic waste and the burning of said waste. The environment is now so polluted that it has sickened residents and harmed much of the area’s agricultural potential.

The area is home to a population of around 2.9 million, and Cannavacciuolo is just one of many who has lived this experience personally. First, his father and uncle, both shepherds, watched as their sheep gave birth to deformed offspring, “with crooked heads and Cubist faces with eyes where they shouldn’t have been,” per La Repubblica’s Riccardo Staglianò. Then, what felt like his whole family was diagnosed with cancer: an aunt, a cousin, two uncles. The level of toxins in his uncle’s blood were at 255 picograms, according to Staglianò’s reporting—the advisable limit is 10.

“Every single day of my life has been affected by environmental problems,” Cannavacciuolo said in an interview with Italy Segreta.

Cannavacciuolo's uncle (in front) and father (behind) when the land was still safe for livestock

In many ways, Cannavacciuolo has become the activist face against what is known in Italy as “ecomafia,” a term coined by environmental association Legambiente in 1994 to publicize illegal acts against the environment, often committed by organized crime groups. For the last 30 years, Legambiente has released an annual report detailing the number of environmental crimes perpetrated nationally, in turn bringing more attention and regulatory power to the phenomenon over the years.

To give a sense of scope, in 2023, there were more than 35,000 illegal actions against the environment, with an average of more than 97 a day, per Legambiente. The most-affected regions were in the South of Italy, what is known as the Mezzogiorno—Campania, Sicily, Puglia and Calabria all ranked high on the list. Naples was, unsurprisingly, the province with the most environmental crimes.

Organized crime groups stood to gain roughly 8.8 billion euro in revenue from these crimes, according to 2023 Legambiente data. For potential perpetrators, environmental crimes offer an appealing equation: “low likelihood of punishment combined with the potential to collect huge profits,” per a 2023 academic paper from Università Bocconi. Companies as far north as Germany may have hired Neapolitan organized crime groups to dispose of their waste, reported The Guardian. Globally, environmental crime is worth an estimated $213 billion a year, according to 2014 United Nations data.

Among what Legambiente classifies as environmental crimes include illegal construction, illegal waste management, and crimes against animals, though violence against cultural heritage is also on the rise.

Yet the recognition of these very acts as serious crimes is a relatively recent phenomenon—in fact, Legambiente created the term in part because of a lack of awareness from law enforcement, political figures, and the public. The first report was presented in concert with the Arma dei Carabinieri, perhaps foreshadowing its influence.

Clouds of smoke commonly hang above the Terra dei Fuochi; Photo courtesy of Alessandro Cannavacciuolo

“We coined this term because we realized that there was no awareness in this country of the strength of the impact of the mafia’s business, from illegal quarries, unregulated construction, public works contracts to illegal waste management, illegal dumping and illegal trafficking of waste,” said Enrico Fontana, head of Legambiente’s environmental and legality monitoring efforts. “There wasn’t an awareness of how serious this impact was and how underestimated it was.”

While the term “ecomafia” nearly predates Cannavacciuolo’s very existence, he defines it easily and with a certain lived bitterness.

“It is a criminal, delinquent organization of people who, simply to make themselves rich, do nothing but destroy their own land,” he said, “creating problems not only for the land itself but also for the very residents themselves and for future generations.”

The “Terra dei Fuochi” was first given that name by Legambiente in 2003, in part because the group had collected reports from residents who were justifiably up in arms about the unending dumping of toxic waste, poisoning their land, their air, and their groundwater supply. By that time, animals were even prohibited from grazing in certain areas, because they were so contaminated with carcinogenic chemicals known as dioxins that are byproducts of burning industrial waste.

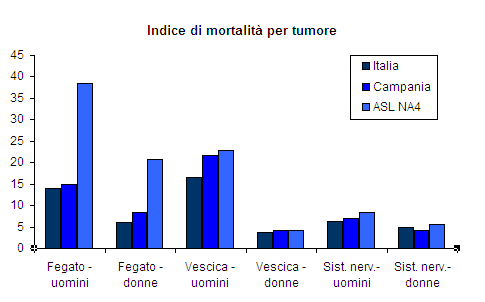

Cancer mortality in the "Terra dei Fuochi" per 100,000/year, from The Lancet Oncology, Vol. 5, No. 9, Sept. 2004: “Italian ‘Triangle of Death’ linked to waste crisis; Courtesy of Di Guarracino

In 2022, the “Terra dei Fuochi” comprised almost 1,500 square kilometers, encompassing roughly 37% of the provinces of Napoli and Caserta and 10% of the entire Campania region, per an article by Silvia Siniscalchi, a geography professor at the University of Salerno. The routine pollution over decades has had a clear impact on the health of its residents—2014 data from Italy’s Higher Institute of Health showed an 11% higher incidence of tumors and mortality rates for men in the area and 9% and 7%, respectively, for women, in the province of Naples. More recent numbers from 2023 show a 9% higher death rate in Terra dei Fuochi versus the rest of the Campania region, according to Guardian reporting from Angela Giuffrida.

But Cannavacciuolo said the ongoing pollution of the area is a problem that has exceeded the geographic boundaries of the so-called Land of Fires.

“If Acerra has had and continues to have the problem of disposing of waste by burning it, you should know that we are not the only ones with this problem, but the entire region and, consequently, the neighboring cities,” he said. “And this is what we have been fighting for years.”

And while these attempts were largely met with silence, residents finally had a glimmer of hope in January of this year when the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Italy had in fact violated article 2, right to life, of the European Convention on Human Rights. The verdict, Cannavacciuolo said, took 10 years from the case’s start, a period he had hoped would be quicker given the severity of the claims.

“The court found in particular that the Italian state had failed to deal with such a serious situation with the diligence and expedition required—despite having known about the problem for many years—specifically in assessing the problem, preventing its continuation and communicating to the affected public,” wrote the Registrar of the Court in a press release on the judgment.

Italian authorities knew of the issue as early as 1988, per court documents, without taking sufficient action. Thus, in the ruling, the court set out a number of specific stipulations for Italy, including that the government must come up with a “comprehensive strategy” to “address the pollution phenomenon at issue,” like “investigating the health impacts” and “combating the conduct giving rise” to it. The court also said “decontamination of areas affected by the environmental pollution” was “of prime and urgent importance.” Finally, the judicial body mandated the creation of an independent monitoring mechanism for complying with the judgment and a “single, public information platform” that would disseminate current information about the Terra dei Fuochi. The court gave a time limit of two years to put these measures in place.

Piles of trash are another common occurrence in the Terra dei Fuochi; Photo courtesy of Alessandro Cannavacciuolo

Cannavacciuolo is watching to see what will happen next. Three months have passed with little impact from the judgment, other than the naming of General Giuseppe Vadalà as commissioner in charge of the case and the allocation of 400 million euro towards the area in the next three years, an amount that Cannavacciuolo says should be in the billions.

“It is a ruling that will certainly be historic and has shaken national institutions,” he said. “But now we expect more targeted action, because, in all honesty, if we are limited by a ruling that only seems to have an impact for optics, we are not interested.”

Fontana echoes this thought, noting the various delays.

“This ruling must be a watershed moment, above all for these areas,” he said. “Because many people live there—the communities that have been affected really do comprise a great number of people, and for so many years, their health has been threatened and they haven’t even been adequately informed.”

Yet in the 30 years since Legambiente’s report on ecomafia, there has been movement from a regulatory perspective in Italy, Fontana said. In 1995, Parliament set up for the first time a commission on the illegal disposal of waste and other similar activities. In 2001, the first crime, organized activity of illegal trafficking of waste, was introduced. And by 2015, crimes against the environment were placed into the penal code.

This has yielded data with astonishing results—from 1992 to 2023, more than 900,000 environmental crimes were reported, according to Fontana. In 2023 alone, 319 people were arrested and more than 34,000 reported in Italy, per Legambiente data.

At the same time, the European Union is also taking a bigger interest in the issue. Last year, the European Commission adopted a new Environmental Crime Directive, which expands the definition of an environmental crime.

A car in Aversa; Photo courtesy of Adriano Amalfi

“This directive puts in black and white the fact that organized crime against the environment is a problem that affects not only Italy, not only southern Italy, but all of Europe,” he said.

In Italy, environmental crimes continue to increase, up almost 16% from last year, according to Legambiente. With almost 5,000 crimes, Campania was the region with the highest amount of illegal activity against the environment. This, Fontana said, is no surprise, given its history.

“Environmental crimes are significantly concentrated in the four regions that have traditionally had a mafia presence, and this is no coincidence,” he said. “The mafia are major contributors to environmental degradation and destroying land. When they enter these markets, like construction and waste, but also when they engage in poaching, they completely flout any rule.”

But having terms like “ecomafia” and “Terra dei Fuochi” that are easily identifiable and communicate a certain message has made some change possible, Fontana said. Both he and Cannavacciuolo hope for more progress, particularly as it relates to the recent judgment from the European court. The alternative, after all, would be too painful.

“Talking about remediation and then doing nothing,” said Cannavacciuolo, “is basically killing these people twice.”