“Save it, there’s no chance you’ll change her mind. She’s Cortina-obsessed.” I smile as my boyfriend responds to our friend’s attempt to lure me across the Veneto–Trentino border for a meet-up in the Alta Badia ski area. She’s blabbing something like “Cortina is old school, and the slopes are too narrow,” followed by: “There are so many people everywhere.” I stay silent, quietly absorbing the insults so often aimed at the tiny village where I spent my childhood summers and winters—a place so beautiful it’s been crowned the Queen of the Dolomites.

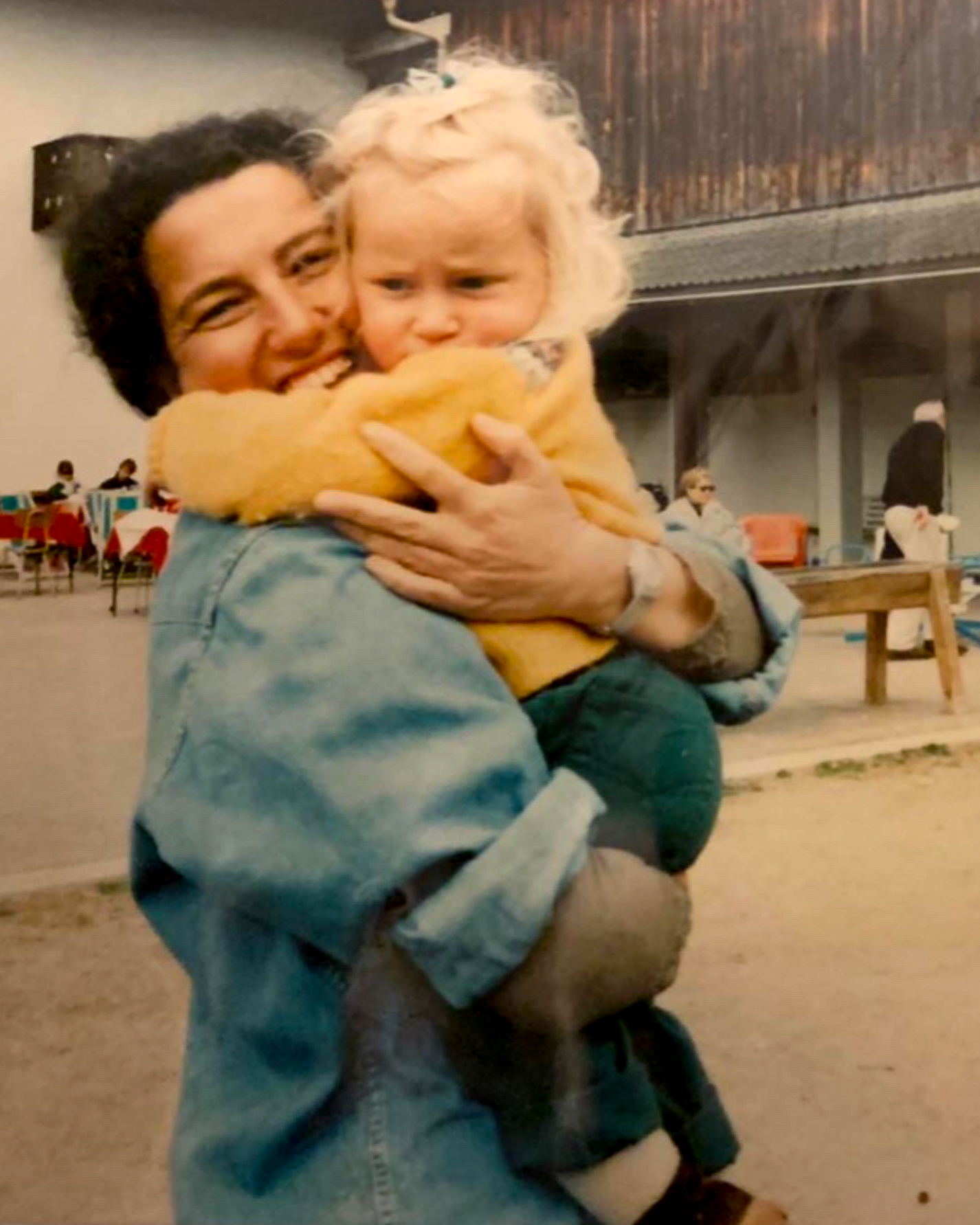

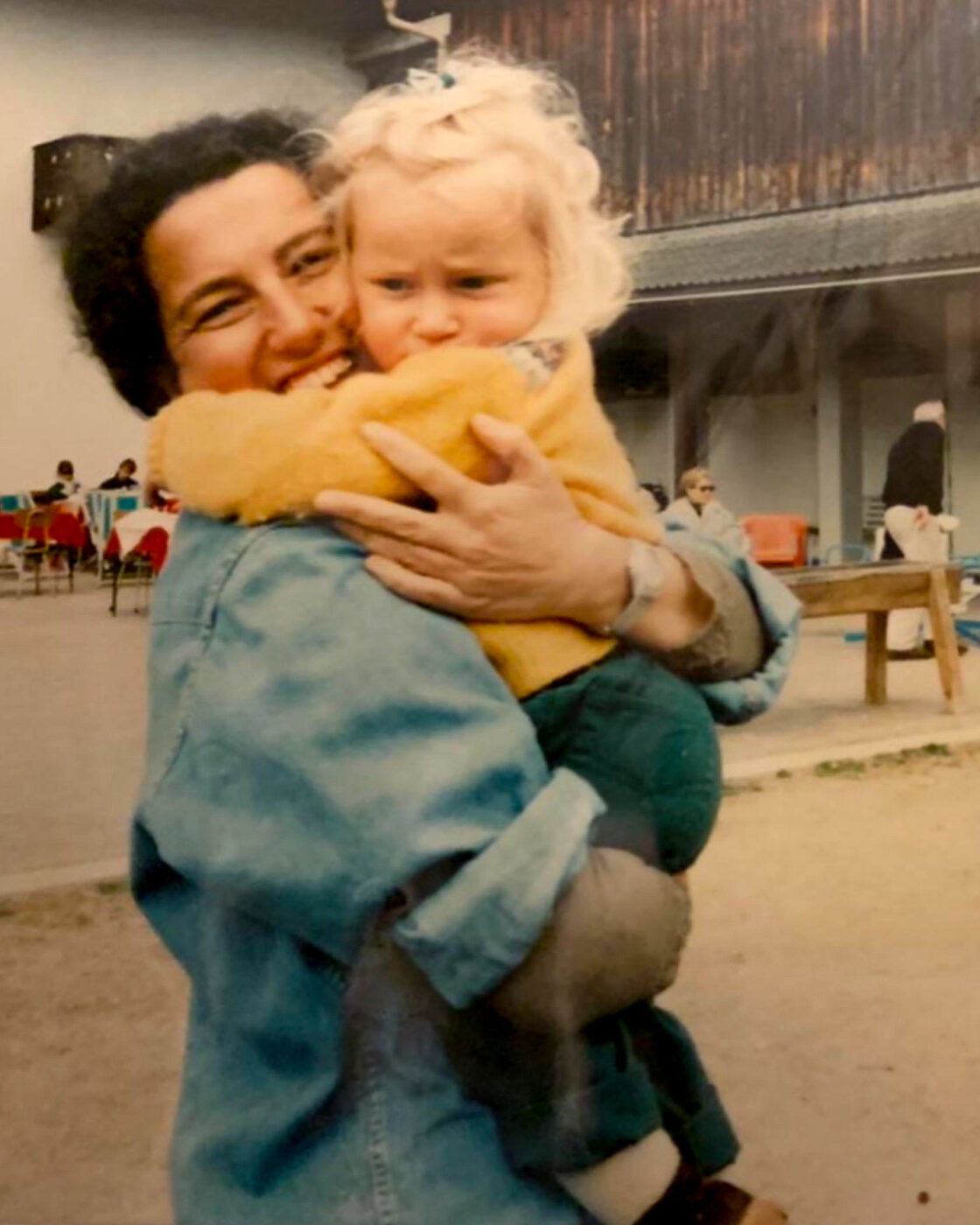

The story between my family and Cortina is older than the one between the valley and the Olympics. My grandma tells me that, after a stint at a friend’s house, she started going, staying in a tiny pension run by nuns in Cortina’s center when she was 16—“you do the math,” she says. When I tell her that would’ve been 1950, she’s shocked: “That long ago? I used to feel like a girl when I took you and Ugi [my younger brother] around the woods of Mount Faloria to pick wild strawberries.”

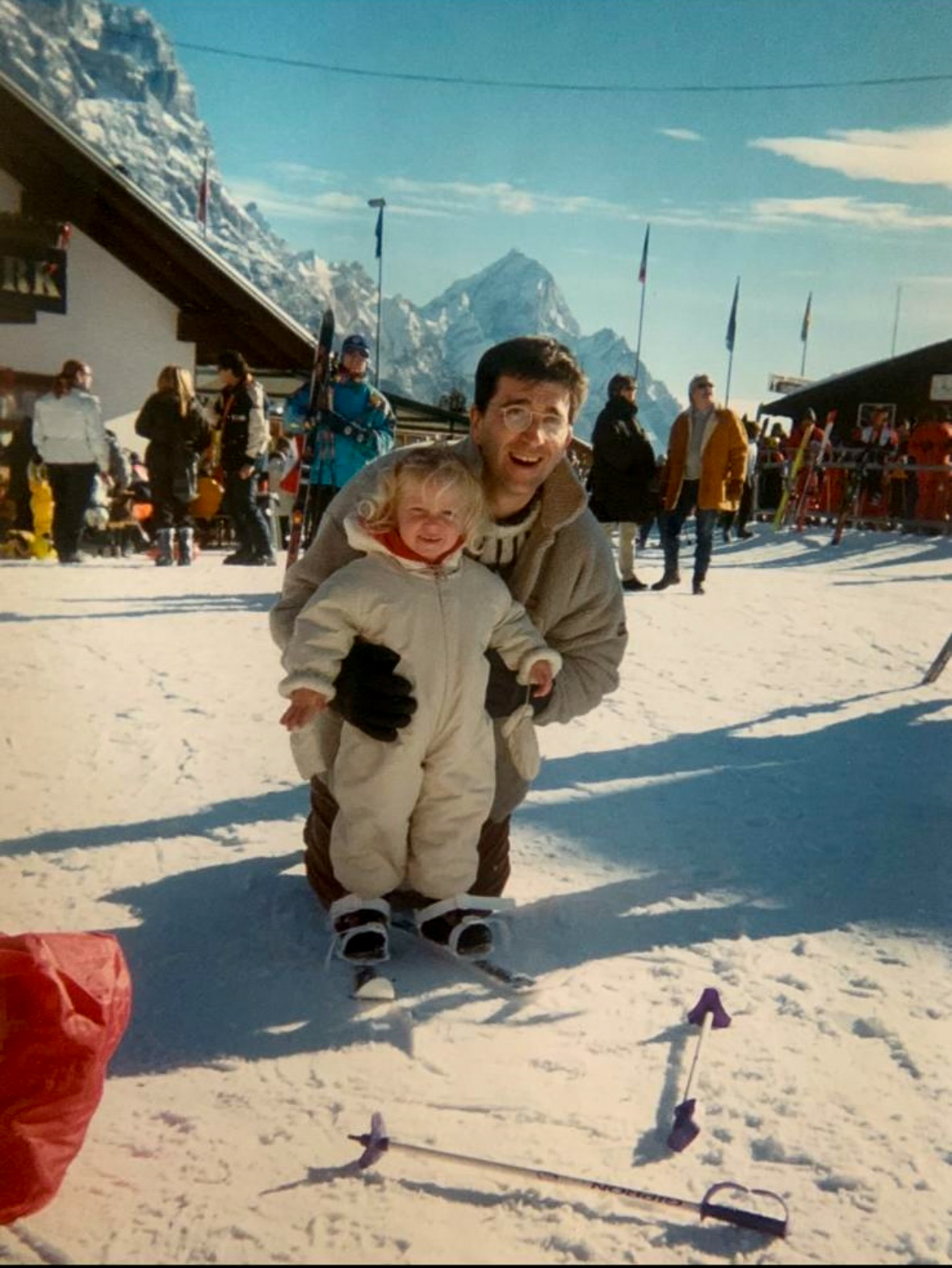

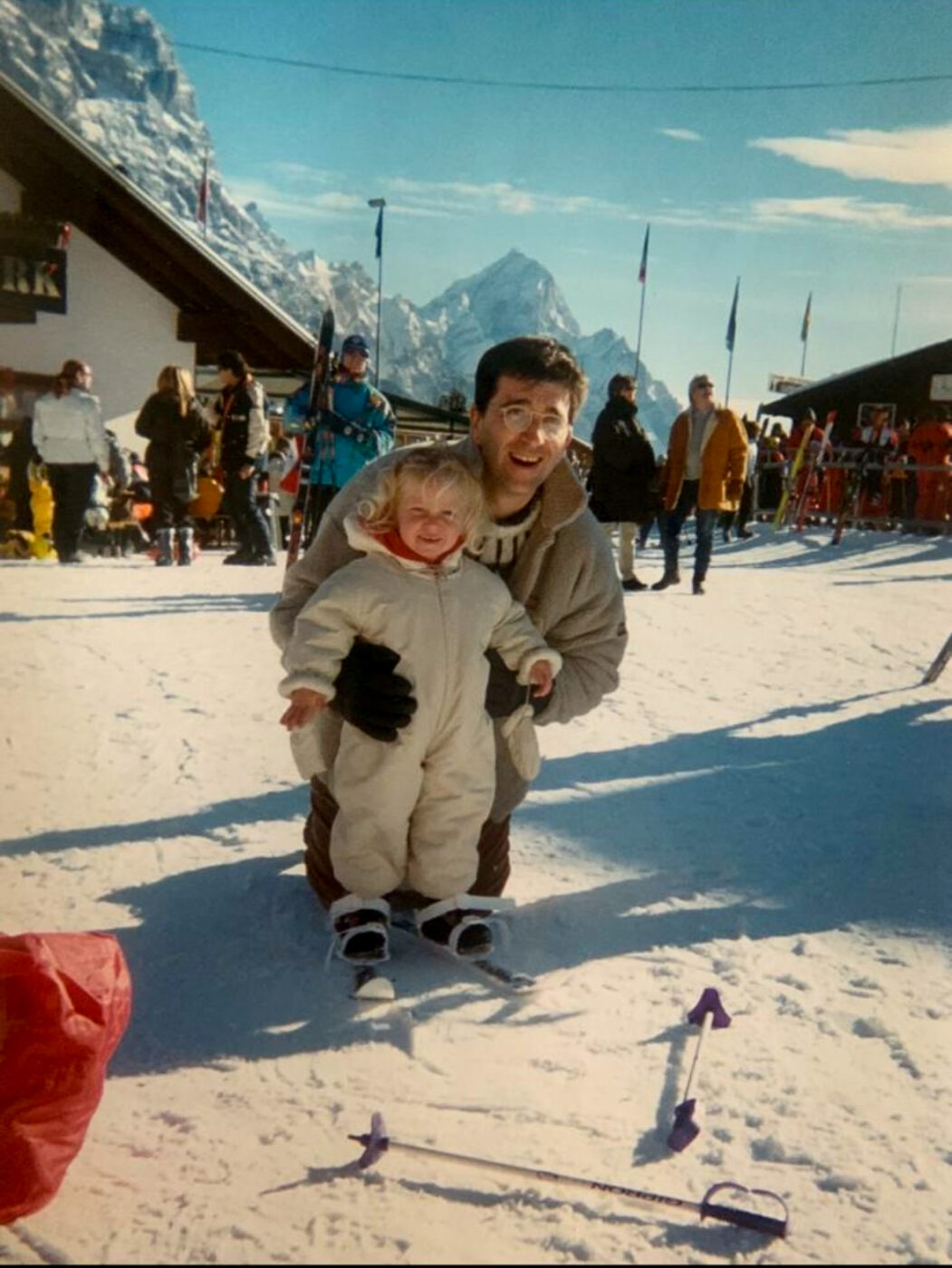

That “girl” was just over 70 years old—a prime example of the effect Cortina has on the women in my family. Up here, they transform into unstoppable superheroes. My mother, who didn’t even hang up her skis during her pregnancies, swam an excessive number of laps in the old municipal pool in Guargné the day before giving birth to me. According to her, she was tired that day and simply “preferred not to cycle there” as she usually did. Faced with such passion, my father and grandfather have had no choice but to resign themselves to spending every free minute in these mountains. I think my boyfriend has realized he will suffer the same fate. Let me share with you what I told him.

Rebecca's mom skied even during pregnancy

Of this place, much has been said. My advice: don’t be dazzled. Forget the long lines at the Tofana chairlifts during the Christmas holidays. Erase the crowds that clog the center over the December 8th weekend. Eliminate the sparkle of golden buckles, the sheen of mink fur, the pressed pleats of the ladies emerging one by one from Liborio.

By mid-January, when the glitter of Christmas has faded and the Carnival confetti haven’t yet colored the cobblestones of the Corso, the Ampezzo valley returns to the place where I grew up. The minks have gone back to the city with their owners—or rest, exhausted, at the bottom of wooden wardrobes—and the only crowd you’ll find is in front of Bar Sport, where the local youth gather.

In the morning, through the glass door of my bedroom, I watch the sun warm the snow. The Bigontina, a small tributary of the Boite, flows just a few meters away, filling the silence in which I drink my first coffee of the day. A few minutes later, after convincing my car to climb up to the Col Drusciè parking lot, I slide my Heads out of the ski rack and pull on my boots. Click, clack. I barely have time to enjoy the feeling of my edges cutting into the snow before I have to stop—take off my skis, sling them over my shoulder—to catch the gondola up the hill.

Until a few years ago, there was an old chairlift here, a relic of the 1956 Olympics, running through the woods, climbing the steep and rocky slope of this little mountain. (Before that, in the late 1930s, there was a sledge lift! I didn’t know what one was until my grandmother filled me in.) My friends and I used to test each other’s bravery by keeping the bar open on that rickety iron contraption, cold beneath our young behinds. We’d cling to the handles on either side during the painfully slow ascent, silently praying our mischief wouldn’t end in disaster. Our laughter drowned out the shouts of our ski instructor, which faded—happily ignored—into the ravine behind us.

Now the gondola glides above the Drusciè A, the slalom course dubbed the most difficult in Olympic history back in ’56. Or, the only slope good enough for my mother to come and vent her youthful frustrations. A pregnant version of skiing legend Toni Sailer, who won one of three medals on these steep gradients, she’d hurl herself down one run after another—always the same one—in a race against herself. My own “release” slope, the Franchetti, lies on another mountain, on the opposite side of the valley. I see it through the gondola window—shadowy as ever—watching me sternly, as if calling me a traitor. But today I have no rage to burn off, only a trace of nostalgia. I just want to rise above the clouds.

Now Drusciè A is wider—my mother would say easier—and it dominates the view as my little cabin nears the top. From here, I can clearly see the traces of lifts past. White, snowy spots sparkling in between the dark green trees. I could do one run, I think, as I take up my skis to get off the lift. Instead, I head for the cable car—I want to go higher, higher still, as high as I can.

Ra Valles slope

Once off the cable car and the next chairlift—if you like things easy, skip Ra Valles—I find myself a few dozen meters above the clouds. The town is hidden beneath a blanket of white; of the bell tower, only the awareness of its existence remains, like the memories crowding my mind. My first skis, my first hangover, my first night dancing on the wobbly terrace of the Belvedere, my first love, and the last one.

The Faloria—where the Franchetti still glares at me from afar—stands tall in front of me. To the right, the Antelao emerges; to the left, the Cristallo and Pomagagnon keep the eye from wandering too far. But most of all, below me, the Bus de Tofana slope, empty as only a Monday in mid-January can be, calls to my skis. I tighten my boots, flex my knees, slip an earbud in. And I throw myself into its arms.

Rebecca's family skiing

I can’t describe the feeling of cutting through snow, of shifting from one edge to the other, of attacking the mountain, of defying gravity with the strength of your legs and hips. I can’t tell you what it feels like to turn right at the end of the Bus, aiming for the Forcella Rossa—never stopping, never braking, always chasing speed, wind, the cold against your face—entering the legend that is the Forcella, conquering it with tight turns, then widening them more and more as the slope opens up, until you end up against the chairlift. Breathless, smiling.

Again. Click, clack. Again and again, until my legs give out—until all the versions of me, past and future, whose eyes have been lost in the gray skies of some European capital, decide they’ve gathered enough memories, drunk their fill of icy speed, brim with euphoric adrenaline. Enough to last until next December.

Local World Cup alpine skier Alberto Tomba's signed photo proudly displayed in a Cortina establishment

You might say that I don’t love Cortina, I love skiing. I watch the sun set behind Antelao as I place my exhausted skis on the roof of the car. Would I love skiing if I didn’t know that this stone giant would guide me home? If I didn’t know that tiredness doesn’t matter because Cristallo will light up, its rock face shining with the fire of the enrosadira (alpenglow)? Would I love it if I didn’t feel that my mother and grandmother were nourished by this fire before me, just as Alberto Tomba, Kristian Ghedina, Paolo De Chiesa, and Yvonne Rüegg were? If Lindsey Vonn, who after the first training session of the season said, “If the Olympics weren’t in Cortina, I wouldn’t even try”?

In February, after 70 years, the Olympic Games will return to the valley. Lindsey Vonn will be back to chase glory, more than 10 years after retiring and over 20 years since she won her first podium on these slopes. It falls to Sofia Goggia and Federica Brignone to try to steal the victory from her. They are all writing the history of skiing and of the Ampezzo valley—and, in some way, my family’s history. One day, it will all become part of the stories I tell my daughter, as I try to pass on to her the thrill of skiing on the shoulders of giants.