It’s all too easy to let melancholy get the best of you on a rainy Sunday afternoon in early June. Most bars are closed, so are shops; indeed, the whole city seems to exist behind closed shutters. However, there is always a place that you can rely on: la cooperativa, with its bar counter made of zinc and old left-wing paraphernalia, a time-capsule of an era bygone. The establishments have mostly disappeared now, but the cooperative di quartiere were once some of the most important meeting spots in postwar Italy. They were places to talk about all things politics–the stronghold of the PCI (Italian Communist Party)–but also places where workers, young people, and the elderly would gather to play cards, chat, have a glass of wine, and eat cheaply.

Renzo

Though the first Italian cooperativa was founded in 1854, its secular rebirth can be traced to the post-WWII Italian Constitution, in which Article 45 recognized the business model as an alternative to private, for-profit enterprise. This setup–in which members would elect a board and a president, and profits would be reinvested in the running of the business or funding social initiatives–could in theory apply to any sort of organization, and didn’t have (at least originally) any political affiliations. Most of all, in the context of postwar Italy, cooperative were mostly an instrument for workers to organize themselves and promote social cohesion, yet another form of associazionismo (associationism). It was only later that–due to the hyper-politicized climate and the style of mass politics espoused by the Italian Communist Party at the time–they became synonymous, in places like Emilia-Romagna and Lombardy, with left-wing culture and a certain kind of bar-osteria.

It’s difficult to explain how central these places were to communities as a whole, but it wouldn’t be exaggerated to compare them to churches, meeting places for believers in a lay religion that, at the time, could rival the country’s ingrained Catholicism. Unlike a regular circolo, or other forms of clubs and associations, the cooperative were for everyone; no paid membership was required, and prices were subsidized so they would remain low and accessible–even now one can easily buy a bottle of wine for €7 and a spritz for €3–as their ultimate goal was to promote an idea of free time as an extension of political militancy and identity. We are too young to remember the heyday of the cooperative, but, growing up, we loved the idea of them and would spend many sweltering summer evenings there discussing Berlusconi’s faults over one-liter jugs of fizzy house Gutturnio.

Renzo and Gianni

This energy of old is mostly gone, but it doesn’t mean that its legacy doesn’t live on–albeit in a slightly different guise. To understand the role of the cooperative today, we visited two: the one we would go to as kids, now even less frequented than it used to be, and another in Milan, which has found another lease on life by adapting to the changing times.

Cooperativa Sant’Antonio, Piacenza

A pergola partly covered in jasmine protects an expansive patio, plastic chairs, and granite tables in neat rows; behind them, a 1950-style building looms. This is how the Cooperativa Sant’Antonio, on the outskirts of Piacenza, looks on a cloudy day in early June. Elderly people are playing Briscola as friends/spectators loom behind them, dispensing advice and exchanging bits of friendly mockery. Inside, the interiors sport an old perlinato–a 1960s kind of wood-paneling that covers the walls. On the counter, paper plates laden with crisps, nuts, and mini sandwiches accompany the odd glass of aperitif while, behind the counter, bottles of Campari and Barbieri punch find their way between the espresso machine, the meat slicer (a requisite for every bar in Emilia-Romagna), and a service notice that says “Non si fa servizio ai tavoli” (“No table service”). A print of the painting Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate) by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, a symbol of class struggle and omnipresent in all cooperatives, sits side-by-side with two yellow Sammontana refrigerators full of ice cream and popsicles–a pop vestige of the Italian 1990s.

Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate) by Giuseppe Pellizza

When we ask Elisa–a tattoo artist who moonlights as an evening bartender–who the regulars are, she points to an older man: “Tato, he is always here.” We never find out his real name; he is simply “Il Tato”, a common vezzeggiativo (term of endearment) for children in northern Italy. He’s sitting at the tables outside playing Briscola with friends in a pink polo shirt; sunglasses rest atop his head despite the fact that it’s not sunny. He is 70 years old and spends nearly all of his retired life at the cooperativa–though a wink indicates it was the case even before he retired. The cooperativa was founded in 1957 and built by workers living in the Sant’Antonio neighborhood on the weekends or during their free time, he tells us.

Gianni, Renzo, and il Tato

Il Tato reminisces about the bottega in the next room that used to sell food to the whole neighborhood. People would go to the coop in the morning to eat breakfast, at lunchtime to have a hot meal, and then in the afternoon to chat with friends and have a bite from the bottega. Though it closed in the 1980s, Il Tato still remembers the discussions locals would have and the initiatives for the neighborhood that they would come up with. “The coop was the social heart of Sant’Antonio. Now there’s just chatting with friends–the ones who are left,” interjects Sergio, an 80-year-old retired bricklayer who resembles Steve McQueen. We look around and realize we’re the only ones under 60 in the entire joint, with the exception of Elisa’s fiancé, a 30-year-old tattoo artist, who confides in us that he comes to the coop exclusively as he would a bar, or rather “what else but a bar?” It’s like living in Gino Paoli’s song ”Quattro Amici”–without the hopeful ending of a generational change.

Sergio (Steve McQueen) and Sergio

“When people traveled less, they really experienced their neighborhoods, and the coop was a meeting point. Now young people go around more and don’t come here.” Renzo, president of the Cooperativa Sant’Antonio for the last ten years, is the next to speak. He tells us that, until a few years ago, the turtlitt ad Sant’Antonï–sweet buns filled with mostarda, amaretti biscuits, chocolate, and dried chestnuts, typical of the neighborhood–were baked fresh in the kitchen in the back almost daily.

Now, however, the kitchen opens only for the Cuncertass, the concert that accompanies Italian Labor Day celebrations every 1st of May, but even this last tradition might disappear for a lack of young people and volunteers. “In the old days, everyone helped each other,” Renzo adds nostalgically. Covid-19, the lack of a generational turnover, and the ever-increasing disinterest in politics have made the coop a version of Stefano Benni’s Bar Sport rather than a social enterprise and gathering place for the community. The remaining patrons tell us that, not so long ago, they’d host singing nights and belt their favorite canti d’osteria while sharing a glass of wine together; they’ve since stopped.

Cooperativa Sant’Antonio

When the subject comes to music, it’s Enzo’s cousin Gianni–a career as a tenor behind him–who takes the floor after throwing an asso di coppe (ace of cups) on the table. He brings us inside, into the small room where the bottega used to be, to show us a photographic archive of Piacenza’s opera singers. Six slot machines light up the photographs–there must be around 50 of them–of opera singers day and night. One of these captures Gianni himself, portrayed in 1983 alongside Pavarotti–he definitely has the physique du rôle. As a send off, he sings us an aria from La Bohème, insisting that it’s “a popular revisiting.”

Gianni singing La Bohème

Cooperativa La Liberazione, Milano

There are many different versions of Milan. Most people, especially abroad, are familiar with Milano da bere, the Milan of fashion and design weeks. There is the “Milano vicino all’Europa” as Lucio Dalla called it–the city of skyscrapers and corporate finance. And then there is another kind of Milan–a working class, hidden one–that still exists, and resists.

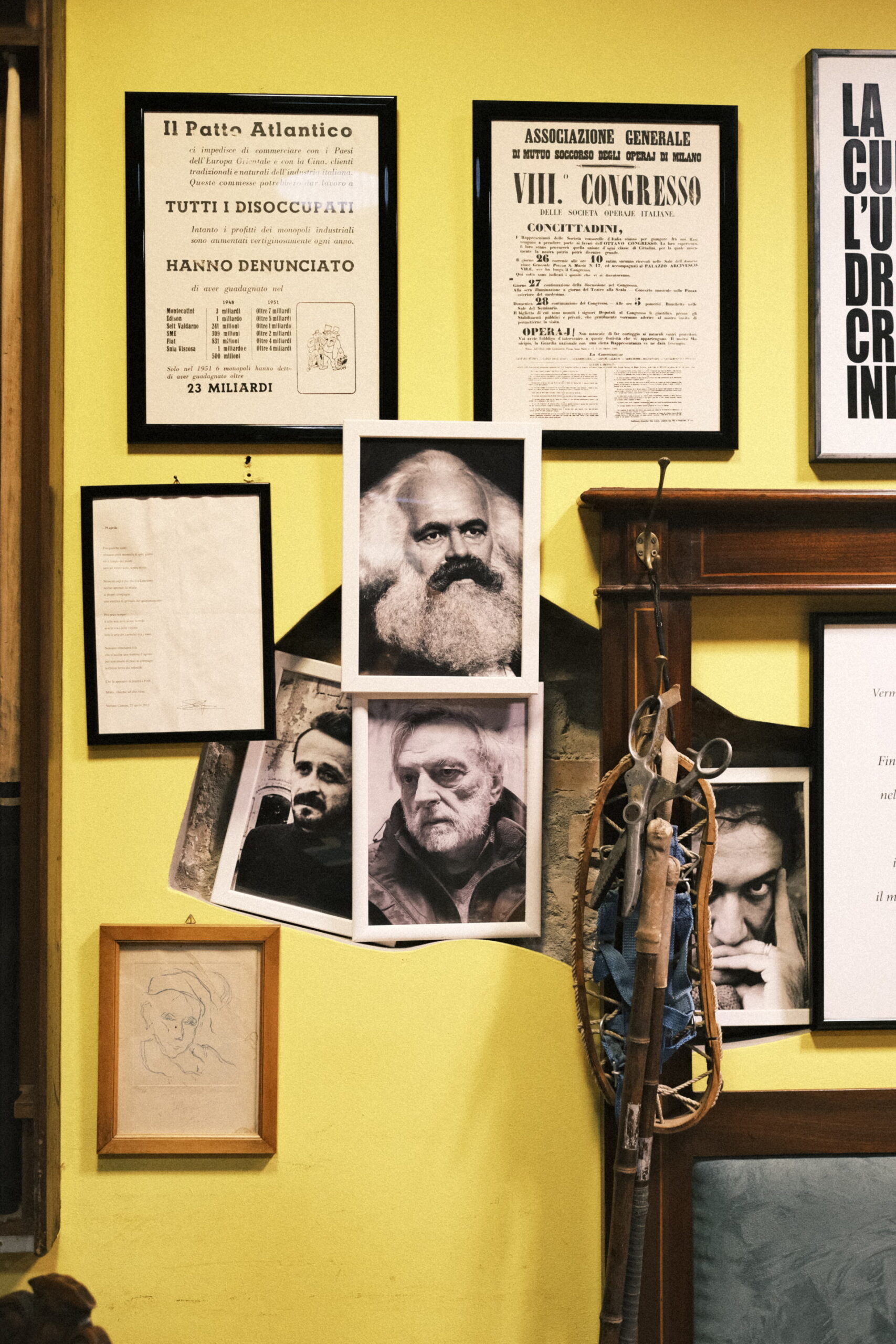

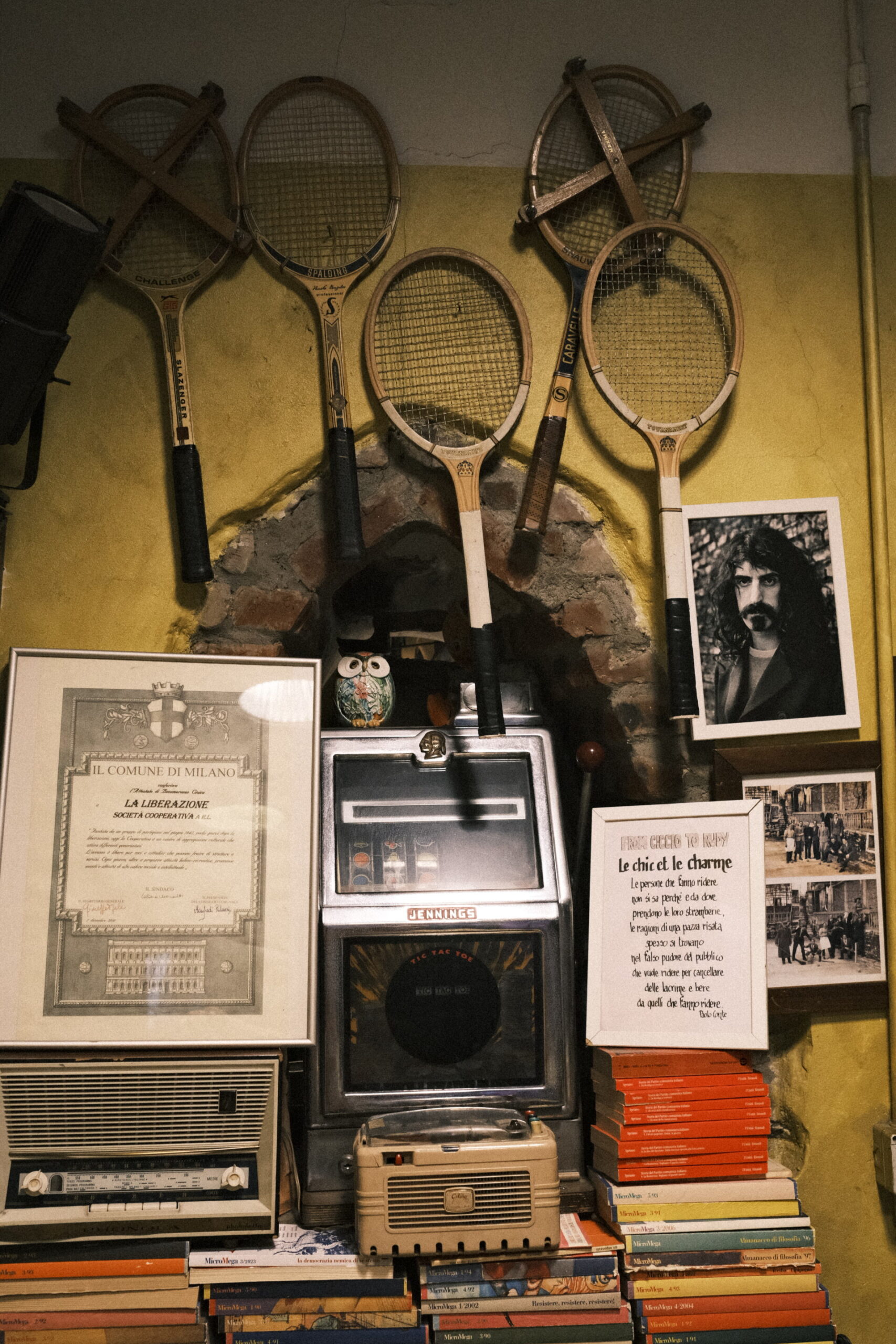

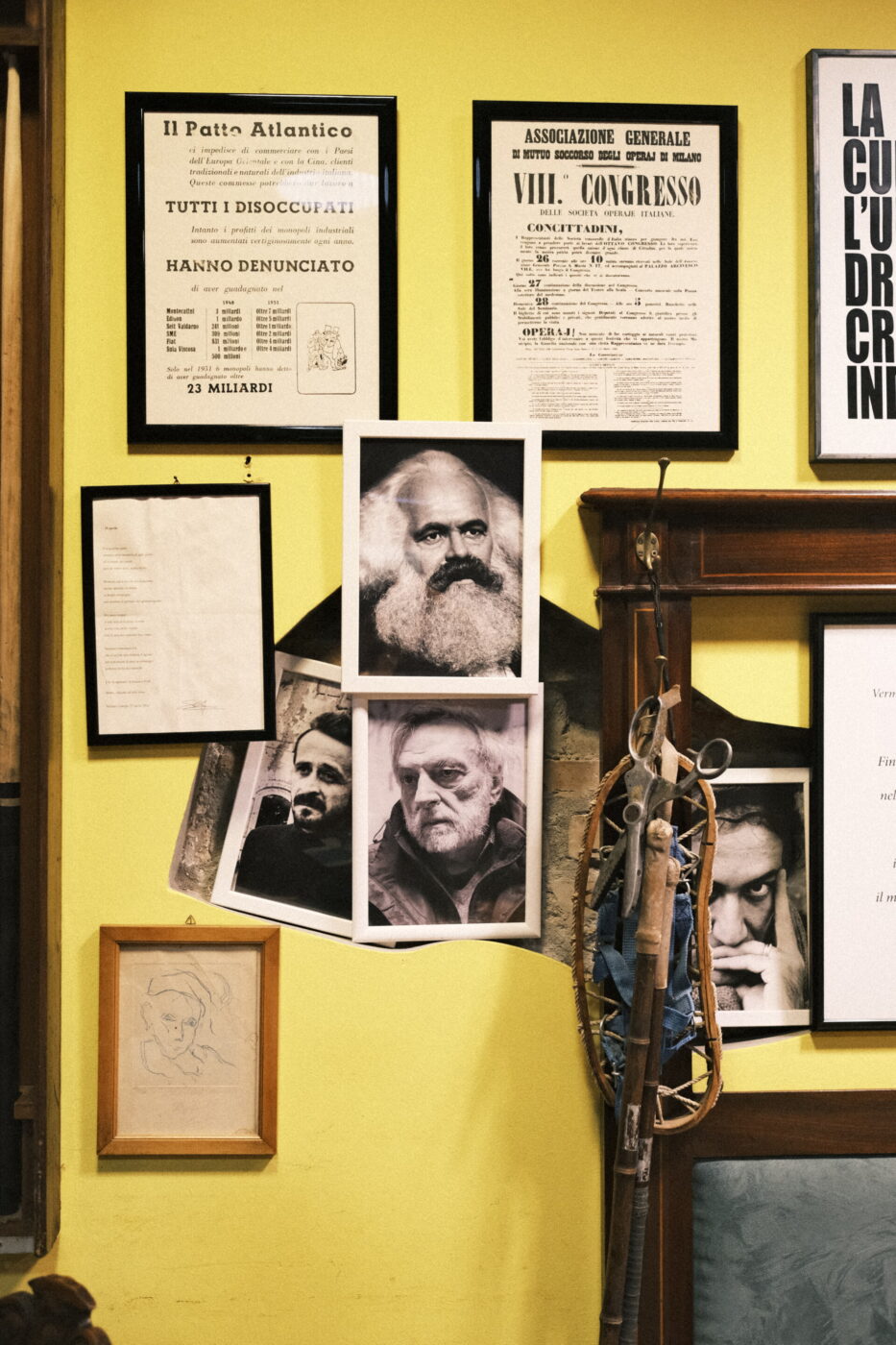

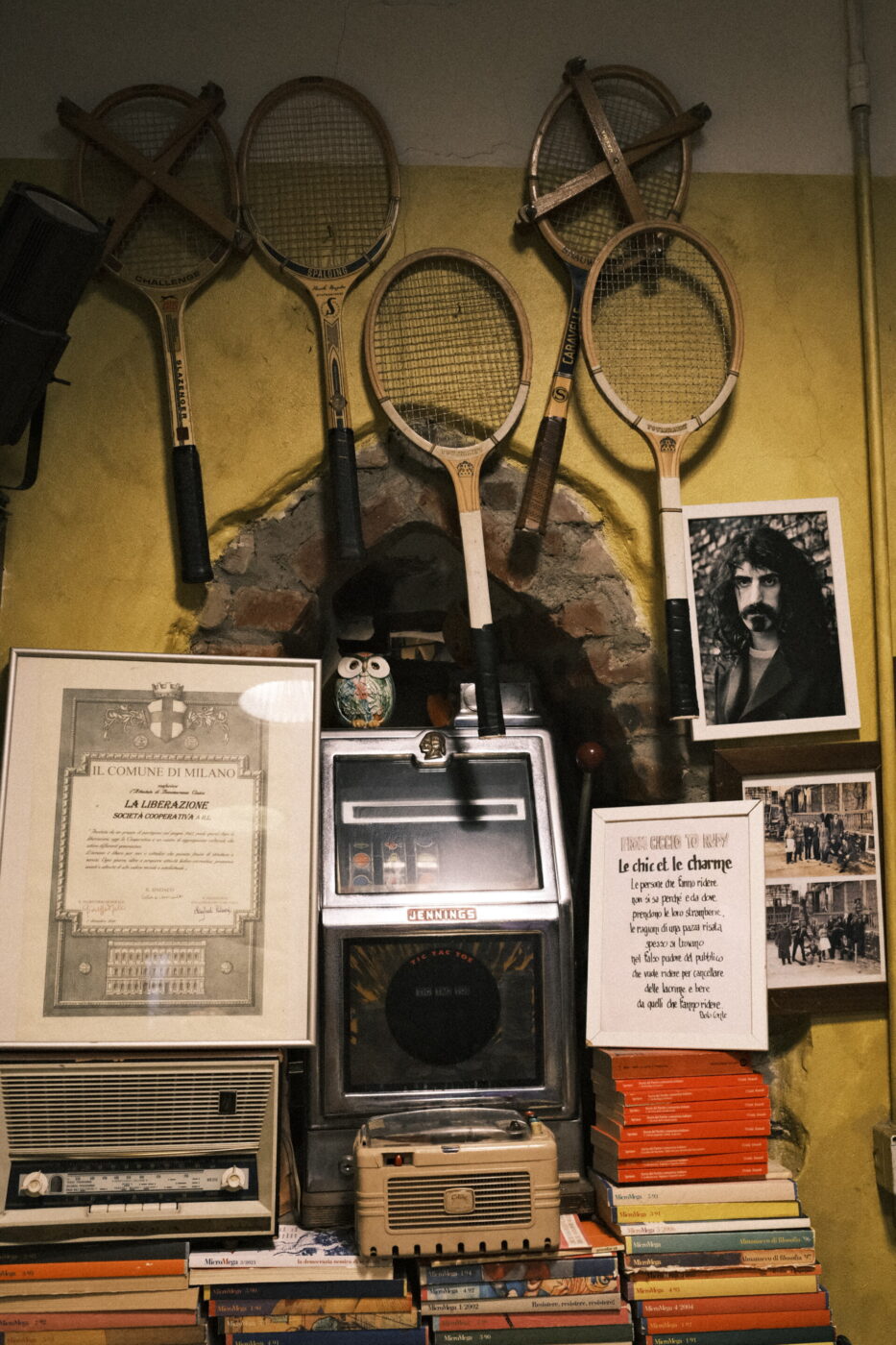

Cooperativa La Liberazione is part of this Milan. Founded in 1946 by the parents of partisan Elvezio Rossi, who was killed by Fascists in 1943, the coop presents itself as a museum of the Resistance, full to the brim with memorabilia from the 1940s. The front page of the Avanti on April 26th, 1945–the day Italy was liberated from Fascism–is displayed, as are giant portraits of Antonio Gramsci and Che Guevara and an unmissable reproduction of Il Quarto Stato–which, fittingly, was originally painted to commemorate workers’ voices during the violent repression of the Milanese riots in 1898.

Cooperativa La Liberazione

The establishment is no longer a center of political organization, though its social soul has remained intact, even in the face of the galloping gentrification of the neighborhood. A menu that changes daily announces simple, regional fare–pasta al ragù, costoletta alla milanese, rognone with purée–for prices that have become unthinkable in the rest of Milan (you can easily have dinner here for under €20). The elderly are few and far between, and patrons are no longer workers, but millennials savoring their aperitivos; the atmosphere is vibrant and convivial all the same.

“What are you writing there?” Damon and Serena come up to us while we’re taking notes on the scene. A couple in their 40s, they’re based in Milan. “La Liberazione is not just a meeting place, it is really a home,” adds Serena, who’s originally from Friuli and has lived in Milan for over 10 years.

They had moved to the Lombard capital for work, changing neighborhoods multiple times after encountering racism, before settling in the Zona delle Regioni, east of Porta Romana. “We felt rejected several times because Damon is a black man, but luckily we found two homes: our house and the coop,” Serena says. Damon is from Washington D.C. and teaches at IULM, a renowned Milanese university of communication. He tells us that, for him, the cooperative embodies the true essence of Milan: every night you can meet different people, build decades-long friendships (he points to a couple of other guys behind us) talk about work and stupid things without ever feeling left out; you can participate in the initiatives, such as book presentations, held every Monday in the big hall inside; or you can simply enjoy a meal at an unparalleled price. Both stress the importance of preserving a place full of values and meanings, and both are part of the generational change that keeps the coop alive.

They introduce us to Renato, La Liberazione’s 80-year-old local authority. He tells us about the bocce court back in the 1950s and how he would spend his time playing, discussing political agendas, and engaging in little battles such as the one “to have the slot machines removed” from inside the coop. His words are full of passion, and we can’t help but notice how they fit better with the history of the place than negronis and glacettes. It’s an interesting paradox. In the province we left behind, cooperative are snubbed by young people, who–when they know what they are at all–consider the institutions to be relics of the elderly. In the city, young people like us–nostalgic for a way of life that we haven’t lived–look for places like cooperative to rediscover a feeling of sociality and community that feels every day more out of reach and elusive. It’s easy to cry for a lost, “better” past, but perhaps, after all, it’s worth looking to see how things might evolve or be reinterpreted for an even better future.