I had been warned. “Once you’re there, you’ll just want to stay inside and not go anywhere else,” my friends Michele and Simone had told me. Chatting over a plate of orecchiette con le cime di rapa about unmissable destinations in Salento–the tip of the heel of Italy–the name Convento di Santa Maria di Costantinopoli invariably came up.

A bed and breakfast housed in a 500-year-old former Franciscan monastery with dazzling interiors, lush gardens, and an impressive ethnographic collection is how my friends sold it–so well that I booked a room on the spot.

While I trusted Michele and Simone on the many wonders of Convento, our conversation left me skeptical over the fact that, however enchanting, any place could stop me from exploring the region: Otranto and the stunning mosaics covering the cathedral’s floor, the uncontaminated beach of Baia dei Turchi, the Baroque buildings made of honey-coloured stones in Lecce… But one afternoon in late July, my husband and I arrive at Convento, on the outskirts of Marittima, a small town in the province of Lecce, a couple of kilometers from the sea.

The unforgiving canicola salentina (dog days) are already hitting hard while we knock at what we imagine to be the main doors of the building: no sign indicates we’re in the right place, and nothing around suggests we’re outside one of the most extraordinary B&Bs in the region. A Madonna and child, painted in bright colors on the facade of the church next to us, look pensive, unbothered by the heat. The church’s finely sculptured cornice is the only element to break the roughness and monotony of the convent’s exterior walls.

Eventually, a cheerful man opens the heavy wooden gate, introducing himself as Pierluigi. We leave our suitcases at the entrance and are guided through a series of tight staircases to the bedrooms upstairs; eight rooms make space for up to fifteen guests.

The walls of ours are covered in Indonesian textiles. Half-closed, the window’s shutters keep the harsh sunlight at bay, muffling the squawking of cicadas coming from the fields outside. A Moroccan rug almost as big as the whole floor softens the atmosphere, while a small bust of Gandhi smirks at me from the top of a shelf. Throwing myself on the bed with my travel clothes and sunglasses still on, I notice the linen sheets: they’re the embroidered, old-fashioned kind I used to sleep in at my grandma’s place.

Photo by Henry Bourne

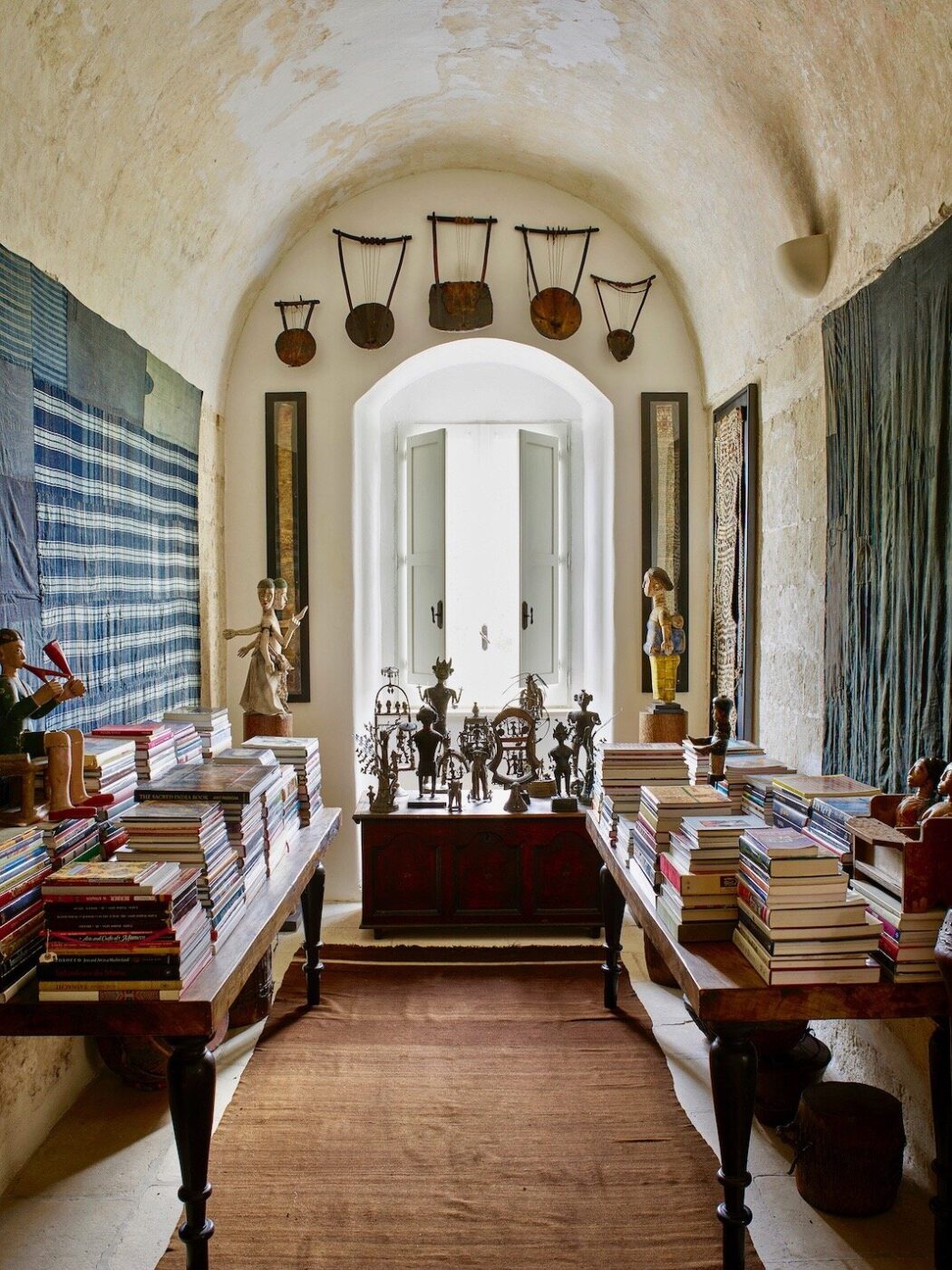

Breaking such an unexpected Proustian spell, I start exploring: a series of narrow corridors filled with bookcases connects the upstairs terraces and rooms. Books are scattered everywhere here, including some fine first editions: arranged by size in neat piles, they stand on the top of cupboards, tables, a number of carved stools and low chairs I presume must be African. While I linger in the library, tilting my head to follow the direction of the volumes’ titles, I notice a pair of stunning textiles on the wall, dyed in several shades of indigo. A group of wooden cabinets displays a gathering of colorful Indian deities. Another collection of figurines and small metal statues sit on top of an engraved chest.

The austere architecture of the convent–after all, it was built by Franciscan monks–is warmed up by the sophisticated yet understated decor of every room. In fact, every corner looks like it belongs in a spread of “The World of Interiors”. Here and there, I notice touches of British eccentricity, like the walls of the main courtyard downstairs, painted in a chalky shade of red that makes the perfect backdrop for the dozens of potted palm trees and other exotic plants embellishing it. The museum-quality collection of ethnography and folk art, with pieces coming from the four corners of the Earth (think Navajo weavings from New Mexico and Kente cloths from Ghana), is gracefully arranged throughout the building.

Dazzled by the place and still a little tired from the trip, we decide to stay in and have an early night.

Photo by Henry Bourne

The next morning, my husband is showing off his knowledge of Swedish, entertaining our fellow guests from Stockholm in front of a lucullan breakfast arranged for us by Pierluigi, when a lady in a bathrobe waltzes into the dining room, perfectly at ease with herself. I recognise her as Athena McAlpine, the convento’s owner, and it occurs to me I already met her, briefly, one evening in Rome.

“I’ve just come back from a swim in the sea,” she tells me promptly, as if to justify her attire.

Athena’s hair, still wet and combed backwards, gives her an elegant, masculine vibe, like a film star from the 1920s.

“I hope you weren’t too warm last night,” she tells me after a long pause. “I put a fan in your room, as I felt it was getting too hot. You see, the convent was built with extremely thick stone walls to keep out the heat–and the invading Ottomans–but sometimes it does get hot,” Athena specifies, while mimicking the act of fanning. I assure her we slept like babies.

An Irish-born Greek raised and educated in England, Athena has been living at Convento for the last 20 years. Her surname, McAlpine, comes from her late husband Alistair McAlpine, Baron McAlpine of West Green, who bought the convent in 1997. By then, the convent had been abandoned by the monks and turned into a tobacco factory, gradually decaying until it fell into the ownership of a local merchant who won it in a card game and used it for his livestock.

Athena is warm and welcoming; her eyes open up wide as she speaks in English with an accent I can’t work out, often switching to Italian, at times stressing a word or a figure of speech by saying it out loud in both languages.

She describes her husband as a force of nature, possibly hiding some pride while she tells me about his many interests. An enthusiastic traveler, Lord McAlpine was a businessman, a horticulturist, a zookeeper–“that was in Australia,” Athena points out–a politician, an author, a publisher. But, above all, Lord McAlpine was a voracious art collector.

He collected British sculpture from the 1960s and 1970s and paintings by Morris Louis and Clyfford Still, not to mention his collections of snowdrops, police truncheons, and political badges. “Peter Halley once told me that Alistair was one of only a few private individuals to have owned a Jackson Pollock,” Athena reveals.

“Once he had put together a collection, he would shed it and start again, re-focusing on one of his other many interests,” she concludes. The textile collection, as well as the ethnographic and the folk art ones now housed at Convento, were among the last he assembled.

“You see, he would find the same beauty in a veil from the Atlas mountains as in a painting by Mark Rothko,” she explains to me. I totally see the point, considering the quality of the textiles hanging in my bedroom.

I ask her how the convent became the Convento. “One evening over dinner–we were already living together in Paris–he told me he owned an ancient monastery in Puglia and didn’t really know what to do with it. So I suggested we renovate it, use it as a backdrop for his collection of textiles, and open a bed and breakfast. And so, for the next twelve years, until his death, we cared for the Convento and the collections together. He died in 2014, and I have continued since.”

Athena disappears as quickly as she had materialized earlier.

Photo by Henry Bourne

As predicted by my friends, my husband and I spend the rest of our holiday in Puglia within the Convento’s walls, lazily dozing by the pool, taking long walks in the gardens, strolling around the corridors upstairs, dining over the savory and uncomplicated food prepared for us: tomatoes and mozzarella (the former of which I never knew could taste so good), ravioli, baked fish, and the countless sweet treats available constantly in the kitchen.

Every time we think about spending a day on the beach of Santa Maria di Leuca, visiting a friend in Castro, or diving into the Grotta della Poesia, we find an excuse to stay in, pampered by Pierluigi and protected by the convent’s walls as if the Ottomans were still around on the attack.

“Once you’re there, you’ll just want to stay inside and not go anywhere else,” my friends had told me. I had been warned.