The United States is in the midst of an extended reckoning: we’re grappling with the reality of the historical figures we once celebrated, the statues we once erected only to now topple them, beginning to understand that the legacies of those we studied in school may not perfectly match their actual lives.

Perhaps the earliest of these figures, at least as it relates to the European colonization of the Americas, is Christopher Columbus, a Genovese explorer who landed in the Caribbean in 1492 at the behest of King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I of Spain. Even those of us farthest removed from our early school days likely recall the nursery rhyme that begins: “In Fourteen-Hundred Ninety-Two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” A newer version meant to expose students to a form of history not told by the victors offers an alternate line to follow: “It was a courageous thing to do, but someone was already here.”

“Someone was already here” is perhaps a fitting way to define the history of the Americas in general, continents founded by an Indigenous people who were then massacred by the conquerors who came centuries later, whether in the form of Italian explorers funded by the Spanish monarchy or an American president who fancied himself the “common man.”

“Columbus really starts being celebrated as a public figure with statues following the American revolution and a new United States, a new country, reflecting on its own history,” Giuseppe Marcocci, professor of Early Modern Global History at Oxford’s Exeter College, tells me. “…You obviously then have this becoming a theme for Italian migrants in the Americas–this is a moment in the late 19th century, early 20th century, when the public use of Columbus is still a very positive thing–this Columbus is obviously a hero, but, for these people, he is also a predecessor.”

Photo by Sebastiano del Piombo

“Columbus really starts being celebrated as a public figure with statues following the American revolution and a new United States, a new country, reflecting on its own history,” Giuseppe Marcocci, professor of Early Modern Global History at Oxford’s Exeter College, tells me. “…You obviously then have this becoming a theme for Italian migrants in the Americas–this is a moment in the late 19th century, early 20th century, when the public use of Columbus is still a very positive thing–this Columbus is obviously a hero, but, for these people, he is also a predecessor.”

The first documented celebration of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas came at its 300th anniversary in 1792, per Il Post. In the 1800s, famed American writer Washington Irving wrote a biography on “A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus” that helped shed light on the explorer’s life and offer him a new level of popularity. But it was President Benjamin Harrison who, in 1892, the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ landing, issued a proclamation calling for a new national holiday: “Discovery Day.” (This was also a reaction to the lynching of 11 Italian immigrants in New Orleans the previous year, according to The Seattle Times.) By 1934, Columbus Day–October 12th–was named a permanent national holiday by Congress and President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Even at that time, 30 Native Americans organized against the event. But for some Italian-Americans, the event became less about the importance of Columbus as a historical figure and more about their pride for their Italian roots–in the 1930s, according to Il Post, the holiday even became a way for Italian-American supporters of Benito Mussolini to celebrate the country’s Fascist government.

Columbus’ public perception really fell under question with the 1980 publication of Howard Zinn’s “A People’s History of the United States,” per Marcocci, which described the arrival of Columbus as a genocide.

“This is not the ‘founding fathers of the future United States’ narrative,” Marcocci says, “but, instead, he’s the beginner of the history of violence and slavery.”

Although Columbus statues were taken down in cities like Los Angeles as early as 2018 (and debated in New York’s Columbus Circle in 2017), the spring of 2020 was a turning point for racial relations in the United States when George Floyd was killed at the hands of police on Memorial Day. The country, one might say finally, was contemplating its history and its legacy of racism. It’s fair to say that this started with Christopher Columbus, who helped to catalyze the death of roughly 55 million people in the Americas from 1492 to 1600. By 2020, Columbus’ controversial legacy was clear, and protesters had taken down at least 33 statues of the Italian explorer by September of that year, according to CBS News. The following year, President Joe Biden officially issued a proclamation recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a holiday that has since been adopted in more than 100 American cities rather than Columbus Day. Biden noted the complicated history of the historical figure in a proclamation for 2021’s Columbus Day.

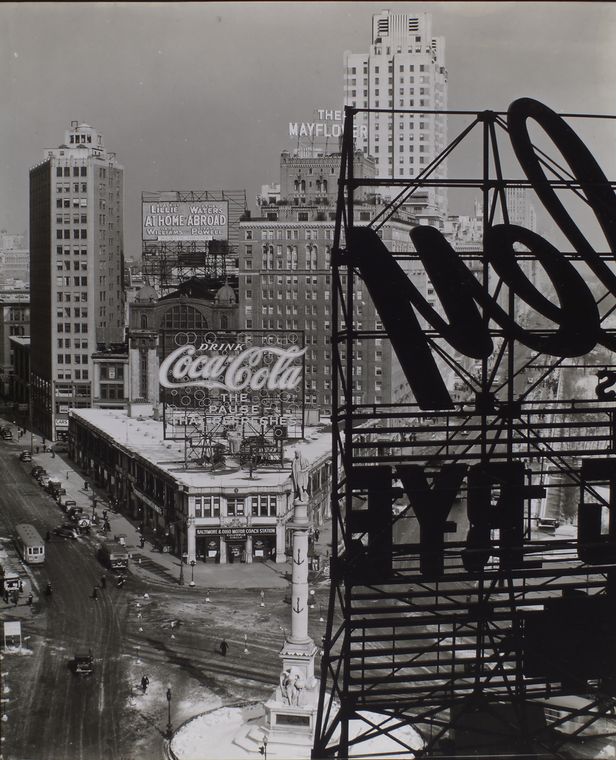

Columbus Circle, Manhattan; Photo by Berenice Abbott

“Today, we also acknowledge the painful history of wrongs and atrocities that many European explorers inflicted on Tribal Nations and Indigenous communities,” he wrote. “It is a measure of our greatness as a Nation that we do not seek to bury these shameful episodes of our past–that we face them honestly, we bring them to the light, and we do all we can to address them.”

But to the newly formed country of Italy, which was only united in 1861, Columbus was brought in as a part of one of the formative stories the nation had to tell about itself. Soon after, a monument to Columbus on a column 60 meters tall, was famously erected in Genova’s Piazza Acquaverde.

“Italy is a latecomer in the history of nation states, so when Italy was unified in the 1860s, there was a need for national myths,” he said. “There is not a national history, not a national narrative, so Columbus is one of the figures chosen in the early days as one of the glorious Italians of the past that entered the pantheon of this new nation.”

Later, Italian fascist thinkers utilized Columbus as a model for the famous saying that Italians are “un popolo di santi, poeti e navigatori” (“a people of saints, poets and navigators”). In fact, Mussolini famously used this phrase, which is abbreviated here, in a 1935 speech in the face of sanctions from the League of Nations–it was later inscribed at the top of the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana in Rome’s EUR.

So suffice it to say that Italians, both those in Italy and Italian-Americans in the United States, have not taken the news of Columbus’ reputation change well, to say the least. In 2004, Italy introduced October 12th as the National Christopher Columbus Day, a day that has “unfortunately been ignored by many Italians,” according to a petition published July 2020 in Il Giornale (formerly owned by Silvio Berlusconi) by Francesco Giubilei, president of the right-wing Fondazione Tatarella who serves on the editorial board of “The European Conservative”, and journalist Marco Valle.

“[This is] an omission that could become a repression or censure in the face of the iconoclastic wave overwhelming the West and that has made the Italian explorer one of its main targets,” they wrote.

Giubilei and Valle go on to implore their audience to remember National Christopher Columbus Day in Italy with “events and initiatives in schools, in Italian universities and in all the institutions” and to celebrate Columbus in Genova on the following holiday, “in defense of memory, history and liberty.” The petition also advocates for a law with “adequate punishments” against those who vandalize statues and historic and artistic heritage.

As the controversy around Columbus stirred, the National Italian-American Foundation released their own statement noting their support for Columbus and opposing “public campaigns that advocate for [Columbus Day’s] elimination as a federal holiday.”

“We believe that Christopher Columbus’ courageous voyage was the catalyst that initiated over 500 years of immigration to the Americas by people from every corner of the Earth–all of whom were seeking a better life for their families,” reads the statement. “…When Columbus Day was made a federal holiday in 1937, it quickly became a source of dignity and self-worth for Italian Americans and (more broadly) Catholics in light of the discrimination that these groups were facing.”

While Columbus’ legacy in America is clear, his Italian legacy is less so. As Giubilei and Valle’s petition pointed out, the wave of re-evaluating historical figures perhaps hasn’t materialized in Italy in quite the same way it has in the United States, or at least regarding quite the same historical figures. After all, Columbus, as he is viewed today, is largely a modern invention, borne of the last 100 years. In Italy, we can see him as the name of prominent roads, of piazzas, and the subject of statues. But the reality, Marcocci said, is that the country, at least in its public discourse, has not truly grappled with its own colonialist history, particularly as it relates to the colonization of Libya and Ethiopia in the 20th century, in part under Mussolini.

“If we had a public debate on Italian colonialism, probably the figure of Columbus would also be revised and discussed in different ways, and it would become more urgent to think about the role of Italian navigators that were not just navigators,” Marcocci says. “In schools, we are not necessarily celebrating Columbus, but we are also not really seeing him as having anything to do with more current problems.”

A conversation on the “Italy” Subreddit reflects the wide difference of opinion between the U.S. version of Columbus and the Italian version. One commenter notes that “he is known for being the one who ‘discovered’ the Americas, and very little more. We take somewhat pride in him being Italian–mainly because of the historic importance of what he did–but he isn’t a very discussed figure.”

Others agree with this attitude of apathy towards Columbus. A similar quandary on Quora offers this viewpoint from Antonella Valcozzena, who notes that “the story of the good and adventurous explorer that arrived in America by chance with his three ships” is “cute,” but that most would not want to be seen as a supporter of colonialism. Ultimately, Valcozzena said, it isn’t discussed much at all–and most Italians don’t think about Columbus enough to have an opinion.

On Reddit, other commenters questioned the general controversy surrounding Columbus.

“What I can’t wrap my head around is why Columbus is so controversial compared to the rest of U.S. history,” wrote “Giorgio_Gabber.” “Yes, Columbus started it all, but it took several nations to complete the colonization and almost exterminate the natives.”

Perhaps the answer is clear from “Landre81,” who notes that Columbus is “more important for Italian-Americans than to Italians.” Is this then what we are left with, a Genovese hero that is not re-evaluated in Italy but in the United States, precisely because that is where he has mattered most?