10 AM in Prato looks different depending on which side of Porta Pistoiese you’re on.

On the city center side, Italians mill past estheticians, clothing stores, and grab-and-go pizzerie, stopping to drink a cappuccino al bar on their way to work. Truck drivers deliver restaurants their daily crates of winter artichokes and radicchio, and the signature Tuscan accent can be heard during conversations in front of the Cattedrale di Santo Stefano.

On the “Little China” side, tavola calda patrons start their day with hot soup and cool soy milk, popping into businesses that bear both Italian and Chinese signage. Restaurants accept deliveries of fresh lychees, enoki mushrooms, and Napa cabbage, and most everyone on Via Pistoiese and Via Fabio Filzi is chatting in some dialect of Chinese.

Prato’s Little China is home to the largest Chinese community in Italy and one of the largest in Europe. Half an hour outside of Florence, the medieval Tuscan town of 195,000 counts around 12% of its residents as Chinese—though undocumented residents are suspected to bump the percentage up much higher. In 2019, Prato elected its two first-ever Chinese city councilors.

Many of Prato’s Chinese inhabitants are second-generation immigrants, born and raised in Italy but not quite considered Italian—by Italians or themselves. Chinese immigration to Prato, mostly from the eastern province of Zhejiang, surged in the 1990s, fueled by growing opportunities in Prato’s long-established textile industry.

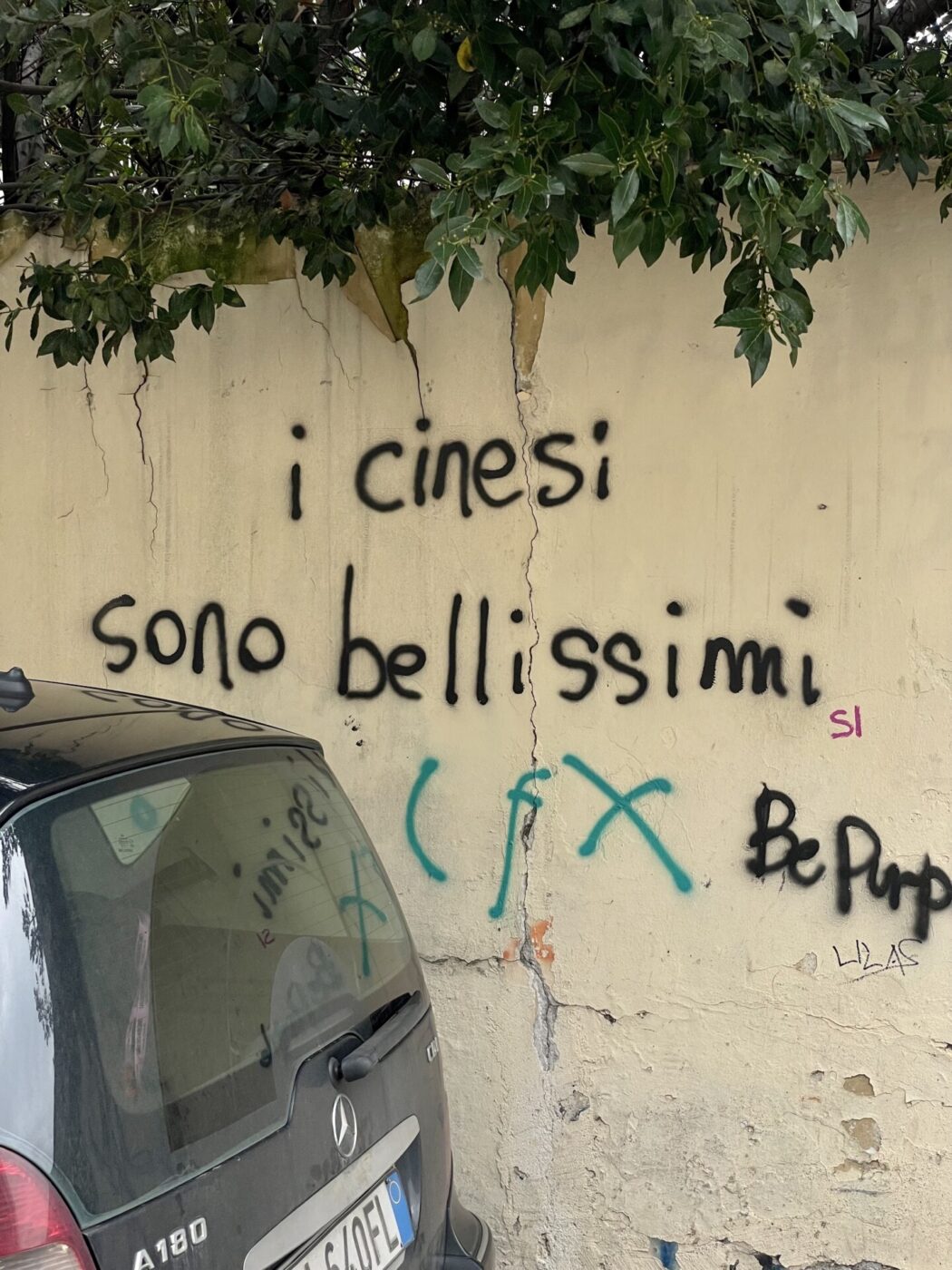

Locals welcomed the immigrants’ low-cost labor at first, but the Italian perception of the Chinese soon soured. Critics say immigrants have diluted the Made in Italy brand by replacing Prato’s historically high-quality fabric production with fast fashion. Others say Chinese workers have simply surpassed Italians in adapting to a globalized economy. Racist rhetoric abounds in Italian media and conversation surrounding Chinese immigrants, accusing them of evading taxes and failing to integrate. But what does integration look like in a city with the highest proportion of foreign nationals than any other in Italy?

Photo by Sara Cagle

“I was raised here, so I do feel Italian. But culturally, I feel half and half,” says Francesca Piao Piao Hu, a Prato-born 24-year-old who works at Yi Fang Taiwan Fruit Tea on Via Pistoiese.

And a 50/50 life Francesca lives indeed: she speaks a Wenzhou dialect with her parents and Italian with her friends. She enjoys Chinese food at home but names lasagna as her restaurant favorite. She prefers Chinese movies and music, and the steadfast Italian value of working to live, not living to work.

Unlike the Italian Pratesi, who won’t hesitate to staunchly correct you if you call them Florentine, the Chinese Pratesi don’t seem to display much Prato pride. Francesca says she likes her life in Italy, but she would pick up and move anywhere for her family. “To me, being home means being together with my parents and brothers,” whether that’s in China or Italy, she says.

Francesca says she sees little difference between Prato’s Chinatown and her family’s town in Wenzhou, the Zhejiang city from where most of Chinatown’s residents emigrate. Though more than 9,000 kilometers apart, there is a link between these two corners of the world. Most of the families Francesca knows back in Wenzhou have at least one contact living in Prato, and many others make a constant back-and-forth between the two places. A 2016 article in Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power explores the experiences of Chinese youth in Prato and describes a 17-year-old, Paolo, whose closest friends include peers who live in Prato and visit relatives in Wenzhou every summer—a unique experience shared only by this specific group of Chinese Pratesi.

Francesca is not the only one who describes Chinatown in Prato as an extension of China. Ming Jie Yu, a 17-year-old waiter at Ravioli Liu, says he has hardly left the neighborhood since he moved here from Fujian province seven years ago. Doing so would push him out of his “comfort zone,” which is speaking Chinese, eating Chinese food, and spending time with his Chinese friends—all in the Tuscan enclave of Prato.

Ming Jie’s experience echoes those of other young people interviewed for Identities, who—outside of the more naturally integrated setting of Italian high school—feel more comfortable around other Chinese-background friends. Though he went to Liceo Marconi and is curious to explore Rome and Milan, Ming Jie says there is no part of him that feels Italian. Having only moved to Prato to be with his dad, who immigrated for work opportunities, Ming Jie says he hopes to return to Fujian.

Chinese residents of Prato are often considered “closed-off” to Italian people and customs. A quote from Paolo in the Identities article may explain why young people like Ming Jie are so quick to say no when asked if they would describe themselves as part Italian: “When I begin to feel Italian, it will mean that I have lost my roots, my culture. I don’t think that is what belonging should be.”

Immigrants all over the world are encouraged (or expected) to learn a new language, embrace local customs, and change their habits to better fit into their new country. It’s purported that these efforts will tear down the social barriers between immigrants and nationals and make newcomers feel at home. But in a place like Prato, where the physical differences between Italians and Chinese are immediately apparent, those with a Chinese background feel irreversibly othered, no matter how long they have lived in Italy. Add frequent discriminatory remarks about food, language, and culture to the equation, and it is harder for Chinese to feel motivated to embrace their Italianness.

Still, not everyone expresses self-identifiers as clear as Francesca’s 50/50 Italian/Chinese or Ming Jie’s 100% Chinese. Some have a more complex sense of self that suggests that the question, “Do you feel Chinese or Italian?” is unproductive.

“I behave as a person, not like a Chinese or an Italian. I am my own person,” said 19-year-old U-lynn, an Identities interviewee who was born in China and moved to Prato at 14. U-lynn’s experience is a reminder that many Chinese-background youth in Prato view their identity differently in various contexts—Chinese with their parents, part-Italian when hanging out with Italian friends, young and aspirational among ethnically diverse school classmates. Monocultural Italian ideals, meanwhile, have not quite caught up with that concept, setting even second-generation Chinese apart socially from their Italian peers.

Many visitors to Prato’s Chinatown come to experience a slice of China in Italy, to eat pork-filled dumplings and shop for luxury skincare at an affordable price. It could be more interesting to come for a different reason: to consider a place where most residents feel between-identities, and belonging is a fluid concept.