The Tuscan town of Leccio is best known for The Mall, a fashion outlet behemoth featuring luxury brands such as Prada, Ermanno Scervino, Roberto Cavalli, and the like, on sale at popular prices. Buses departing regularly from Florence city center ferry tourists to and fro this glorified strip mall, which gets a similar number of yearly visitors as the Uffizi Gallery, making it de-facto one of the main attractions of the city on the Arno. You might see it as a convenient and aesthetic spot to cop some otherwise unaffordable gear, or you might find it to be a monument to consumerism and a cheapening of high couture. But the little Leccio could have something else going for it. If you were to drive into town from the opposite side, coming from Figline Valdarno for example, you might spy a curious red stoned palace emerging from the oak trees up on the hill to the right, and you might care to know that this is one of, if not the, most important piece of Orientalist architecture in the whole country: the Castle of Sammezzano. And the reason you may have heard of The Mall, but not this architectural marvel, is because the castle has been lying in a state of disrepair and abandonment for over 30 years.

During the first COVID lockdown, I found myself stranded at the literary foundation I was working at in the countryside near Reggello. In the middle of nowhere, with my boss as my sole company, I took to long walks in the forest. It was she who first told me of an abandoned castle called Sammezzano on the next hill over. I set out, uphill into the forest, then downhill, all the way to the valley, left into an open field, then right, crossed a river, and uphill again; the first signs that I was in the right place were the gigantic Redwood trees, which the reader may know are not native to anywhere in Europe. Then I saw it: a Moorish facade, clock tower at its center and two symmetrical spiral staircases leading to an arched entrance. The rear entrance to the castle, this facade is meant to represent the moon, while the other side, the front, is for the sun. Deterred from entering by fencing and security cameras, I resigned myself to a simple walk through the gigantic Sequoias around the castle’s park. I stumbled upon a twinned pair joined at their base, standing at a whopping 54 meters, making it the fourth tallest tree in Italy. Just a few meters away, a cement skeleton loomed–a failed attempt to add a new building to the complex, a reminder of the mismanagement that has plagued this place in recent years.

It is not known exactly when the structure that was to become Sammezzano was originally built, but it’s generally agreed that it stands over the ruins of an ancient Roman fort (which, according to German historian Robert Davidsohn, hosted Charlemagne in 780 AD, when the king was on his way back from his son’s baptism, at the hands of the Pope, in Rome). The castle was later passed into the hands of the Altoviti family, who Cosimo I de Medici exiled to Rome and whose confiscated property, including Sammezzano, was gifted to Giovanni Jacopo de Medici. Giovanni would sell it to Sebastiano Ximenes, the scion of an Aragonian family transplanted to Italy. The last of the Ximenes line, Ferdinando, died heirless, and so his titles and deeds passed to his sister Vittoria, who married into the noble Panciatichi family. The man responsible for Sammezzano as we know it today was her grandson: Ferdinando Panciatichi Ximenes d’Aragona.

Botanic, architect, politician, businessman, Ferdinando was a renaissance man through and through, despite never possessing a diploma. He benefited personally from the union between the Panciatichi and Ximenes fortunes, and sat on the city councils of Florence, Reggello, and Rignano sull’Arno, all the while donating large swaths of his books to what was to become the Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze, as well as art from his personal collection to the Uffizzi, the Bargello, and the Accademia di Belle Arti. But his pet project became Sammezzano, which, over the course of 40 years, between 1853 and 1889, he would transform into a monument to his own personal folly and hubris. Ferdinando was an admirer of Orientalism, possibly stemming from an attachment to his Iberic roots and the Moorish architecture popular in Spain, and believed that the Italian Renaissance had its roots in the east. He famously never traveled in that direction, instead studying the quirks of this architectural style in books, and drawing the blueprints himself, while hiring local artisans as laborers. The furnace for the tiles was placed directly in the garden, so that Ferdinando could oversee even the minutiae of construction.

Sammezzano became his personal sanctuary, away from the politics and troubles of the city. He had been sympathetic to the Nationalist cause, and personally helped fund the unification of Italy, but quickly grew disillusioned with Italian politics–a fact easily understood by the inscriptions carved into his castle. One such inscription, in the Gallery of Stalactites, reads: Pudet dicere sed verum est publicani scorta – latrones et proxenetae italiam capiunt vorantque nec de hoc doleo sed quia mala – omnia nos meruisse censeo. I’m ashamed to say it, but it’s true, Italy is in the hands of thieves, prostitutes and middlemen, but it is not this which pains me, but the fact that we deserved it.

Hall of Peacocks

I was fortunate enough to be able to enter Sammezzano, in 2021, about a year after my first visit, as part of a tour organized by FAI (Fondo Ambiente Italiano). I believe it was the last time that the castle has been open to the public, as its crumbling state presents safety hazards for visitors and disputes with the owners carry on.

It’s widely reported that Sammezzano counts 365 rooms, one for each day of the year, but in truth there are only about 60. Yet the castle is proof that quality reigns over quantity, for every detail goes to show the complex superciliousness of the man who built it.

The gothic inscription “NON PLUS ULTRA” (“no more beyond”) welcomed us to the entrance halls, known as the Atrium of Columns. According to legend, the same phrase was engraved on the Pillars of Hercules at the Strait of Gibraltar, warning sailors not to venture beyond the known world. Here, the walls are plastered with lilies, the symbol of Florence, and red, blue, and gold Graeco-Roman architecture merges with the Middle East. Tinted glass windows on the ceiling allow the sunshine to come and play, turning what was more of a rusty red ruby-colored under the rays.

Atrium of Columns

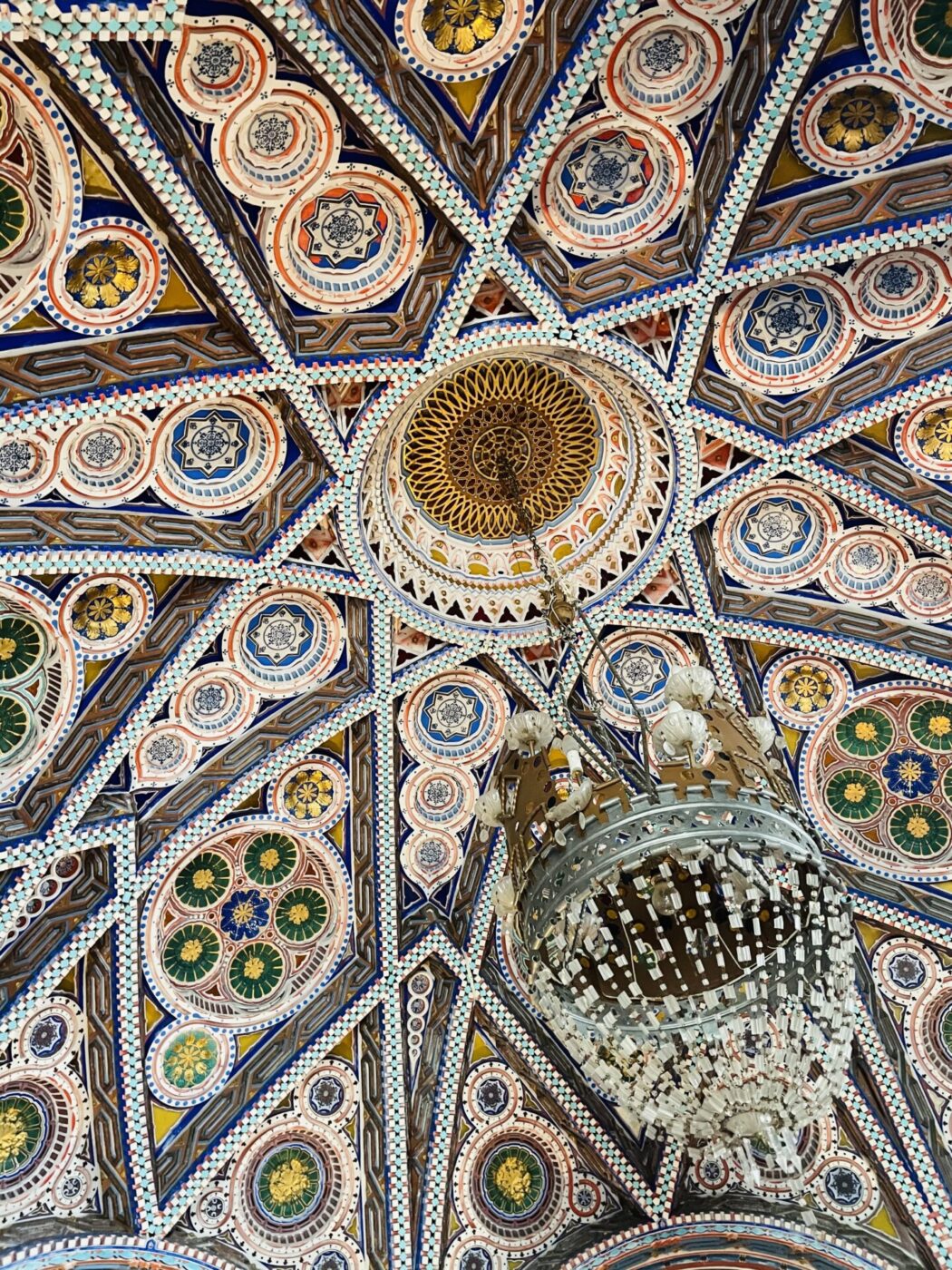

Moving into the octagonal Dance Hall, also known as the White Hall for its blindingly predominant color, we find a domed ceiling surrounded by arched windows, mirrored in the arched entrances and exits below. One arched hallway leads to the aforementioned Gallery of Stalactites; there are beautiful azure majolica tiles, but it’s the green-blue-red muqarnas, which look like falling stalactites, that give the room its name and its cavernous character. Next, the Hall of Lilies, with dozens of tinted glass circles. Four mezzanines square off the space, built for four violinists to immersively serenade whichever lucky aristocrats snagged an invite. But perhaps most majestic of all is the Hall of Peacocks, inspired by the Indian Mughal artistic current, and by the interior design of Westminster Abbey, a design interpreted here in a much (much!) more colorfully kaleidoscopic way. Like the tail of the room’s namesake bird, fan-like structures ripple up from the ground, opening up on the ceiling like a prismatic rainbow. The whole thing feels like an acid trip. The BBC named it one of the ten most beautiful ceilings in the world, an opinion shared by Thierry Mugler, who chose it as the background for his Alien perfume ad campaign.

But what struck me, more than the pure ostentatiousness and the technicolor, was the personality of Ferdinando Ximenes, immortalized in stone and on full display. Rather plain–by Sammezzano standards, that is–the Hall of Oaths is designed so that the eyes concentrates on an inscription above the chimney, a challenge to the King of Italy: “Ancient oath of the nobles of Aragon, each one of us which is as great as you are, and together more, we swear obedience and loyalty to Your Highness, so long as you maintain intact our rights, our freedoms and our privileges, and if not, then no. So may god help us.” Ferdinando drives his philosophy home with other minor engravings throughout the property. Among them: “Frangar non Flectar” (“Break, don’t Bend”) and “abstine, substine” (“abstain and support”), a motto from the Greek stoic philosopher Epictetus.

When Florence was chosen as the capital of Italy, Ferdinando made a fortune selling off his properties in the city, which were to be demolished to make way for the new beltway. He used the money on Sammezzano, and was derided by fellow Florentines for wasting his fortune on plaster and gypsum. But Ferdinando cared little for their opinion. In the Hall of Lovers, one of the later additions to the castle as it was previously a terrace, we read “Gracchi me sibilant at mihi plaudo” (“The populace hisses at me, I applaud myself”). And again, in the same room: “Est aliquid delirii in omni magno” (“Every great man has some folly”). He died in 1897, and, during his memorial service, the eccentric was reportedly defined as a “a little stain”. Whether this apocryphal story is true or not, it does seem that this man has been unjustly wiped, like a stain, from the history of the city.

Upon Ferdinando’s death, Sammezzano passed to his daughter Marianna, and from there until after World War II the historical record is spotty, as it was a private home for the family. In the 1950s, the castle was converted into a luxury hotel and restaurant, and was used as a setting for a number of films, including Arabian Nights by Pier Paolo Pasolini and I Am an ESP by Sergio Corbucci. You’ll also find Sammezzano featured in the music videos for Fiordaliso and Pupo’s La Vita è Molto di Più and Amedeo Minghi and Mietta’s Vattene Amore, which took home 3rd place at Sanremo in 1990.

At some point in the 1990s, the hotel went bankrupt–excessive maintenance costs was the excuse–and Sammezzano was abandoned. In 1999, it was sold to a British-Italian company, Sammezzano Castle srl, which had plans to renovate the area and continue its use as an upscale hotel. It’s this company that’s responsible for the aforementioned cement monster, the beginning of what was to be a new building for the hotel, but, due to mismanagement and lack of funds, never managed to get off the ground.

Sammezzano Castle srl has gone bankrupt at least twice, most recently just last year. They’ve tried to get rid of the Brobdingnagian burden, and the castle has been up for auction a number of times: in 2017, it was bought by a company from Dubai, Heliotrope Limited, but the sale was quickly deemed invalid on some technicality or other and the property returned to Sammezzano Castle srl. Sammezzano can, today, be purchased for around 20 million euros, but it’s falling apart and there are restoration and maintenance costs–in the order of millions too, as restoration would require specific skilled experts. Last year, the Ministry of Culture expressed interest in purchasing Sammezzano, but no movement has been made on that front. While the castle falls apart, a few institutions have taken its cause to heart: there is the FPXA committee, whose explicit purpose is to raise awareness about Sammezzano’s cause; the aforementioned FAI, which placed Sammezzano at first place in the 2016 edition of I Luoghi del Cuore, a campaign to raise awareness about at-risk places in Italy; and Europa Nostra, a pan-European NGO which included the castle in its “7 Most Endangered Heritage Sites”.

The Castle of Sammezzano may be unique and remarkable in the history of Orientalist architecture, but its plight is not. Rather, its story is representative of the state of Italy’s heritage sites as a whole. The country is littered with churches, monuments, castles, and more in states of disrepair, unknown to the general public. Investing in proper tourism infrastructure should be a no-brainer for a country which relies on tourism for such a significant chunk of its economy, and yet we seem to fall behind other Western European countries in this regard, countries that arguably may not have as much potential on offer. Restoring Sammezzano is not impossible–the place is not doomed–it just requires the right investor.

Head 120 kilometers north, up into the Emilian Appennine, and you’ll find another such place, one which did get the right investor. The Rocchetta Mattei is also an Orientalist castle from the 19th century, also built by a quirky aristocrat, also abandoned and in a state of decay for a number of years. In 2005, the fairytale-like residence was purchased by Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna, which has been restoring and maintaining the property while allowing paid visits on weekends. I don’t know if the challenges of its reconstruction were as great as those of Castello Sammezzano–no numbers are publicly available on the amount of purchase, nor details about its condition before restoration–but here’s hoping that Sammezzano can meet a similar fate, allowing us to enter Ferdinano Panciatichi Ximenes’ folly once again, before it collapses for good.