THE GAME

It’s June in Florence. The city center is buzzing, and we join the migration of locals heading towards Piazza Santa Croce. The square is closed off, allowing us to circle it through the poorly cobbled side streets and alleyways. Florentines, and a few beer-guzzling Brits, wait dressed in either red, Rossi, or green, Verdi, signifying their allegiances to the teams playing in the upcoming Calcio Storico semi-final. Many wear face paint and ripped t-shirts–there are even a few who are shirtless–a stark contrast to Florentines’ usual reserved elegance.

With prime spots on the Verdi bleachers locked down, we face the neo-Gothic facade of Santa Croce looming over the piazza–which, these days, is a 5,000 m2 sand arena called the sabbione. A flag-throwing routine precedes the game, and the flag-bearers, primarily elderly Florentines, seem hot and bothered under the boiling summer sun in their pantaloons and Renaissance garb–a reminder that Calcio Storico is not just a game, but also a historical reenactment.

The winning prize–a calf of the local Chianina breed–is paraded in. Tension builds. A blanket of red flags from the Rossi bleachers tease us, and we Verdi fans counter with a massive banner that unfurls over our heads as shouts of “Forza!” echo underneath. Shirtless teens climb the wire fence, straddling it as they set off acrid smoke bombs, coloring Santa Croce temporarily green. The procession is finally making its way off the field; just the two teams, of 27 players each, and the referees remain. As they square up, you can see that the players are the types of guys that have most likely raised the Florentine height and weight average by a good 30%. A rather demure-looking elderly woman hurls a string of expletives at Rossi. A culverin shot is fired, the red and white ball is thrown into the air, and the game is on.

Like many ball sports, the goal of Calcio Storico is to get the ball into the opposing team’s net, which, in this case, runs the width of the piazza. Unlike many ball sports, you can do so by pretty much any means necessary. There seems to be a standard strategy: the fighters, who man the front of the field, must box/wrestle/fight members of the opposing team, pinning them down and clearing a path for the ball carriers. Passing among themselves, the ball carriers must make a mad dash to the net before they can be tackled or body slammed. After a player had his eye gouged out some years back, a few rules were implemented–no hitting from behind and no ganging up on one player–but what goes and what doesn’t is up to the discretion of the referee. With so much chaos, it’s a tough job to catch every infraction.

The semi-final the day before saw the Azzurri eliminate the Bianchi to cement their place in the final, to be played, as is the case every year, on June 24th, a day of celebration for the city’s patron saint San Giovanni. There are four teams in total, each tied to a neighborhood, and Basilica, of Florence: the Azzuri (blues) of Santa Croce, the Rossi (reds) of Santa Maria Novella, the Bianchi (whites) of Santo Spirito, and the Verdi (greens) of San Giovanni. Everyone in Florence supports one of the four teams, usually that of the neighborhood in which they were born, and it’s not uncommon to see flags and photos of calcianti (players) hanging in their favorite restaurants year-round.

THE HISTORY

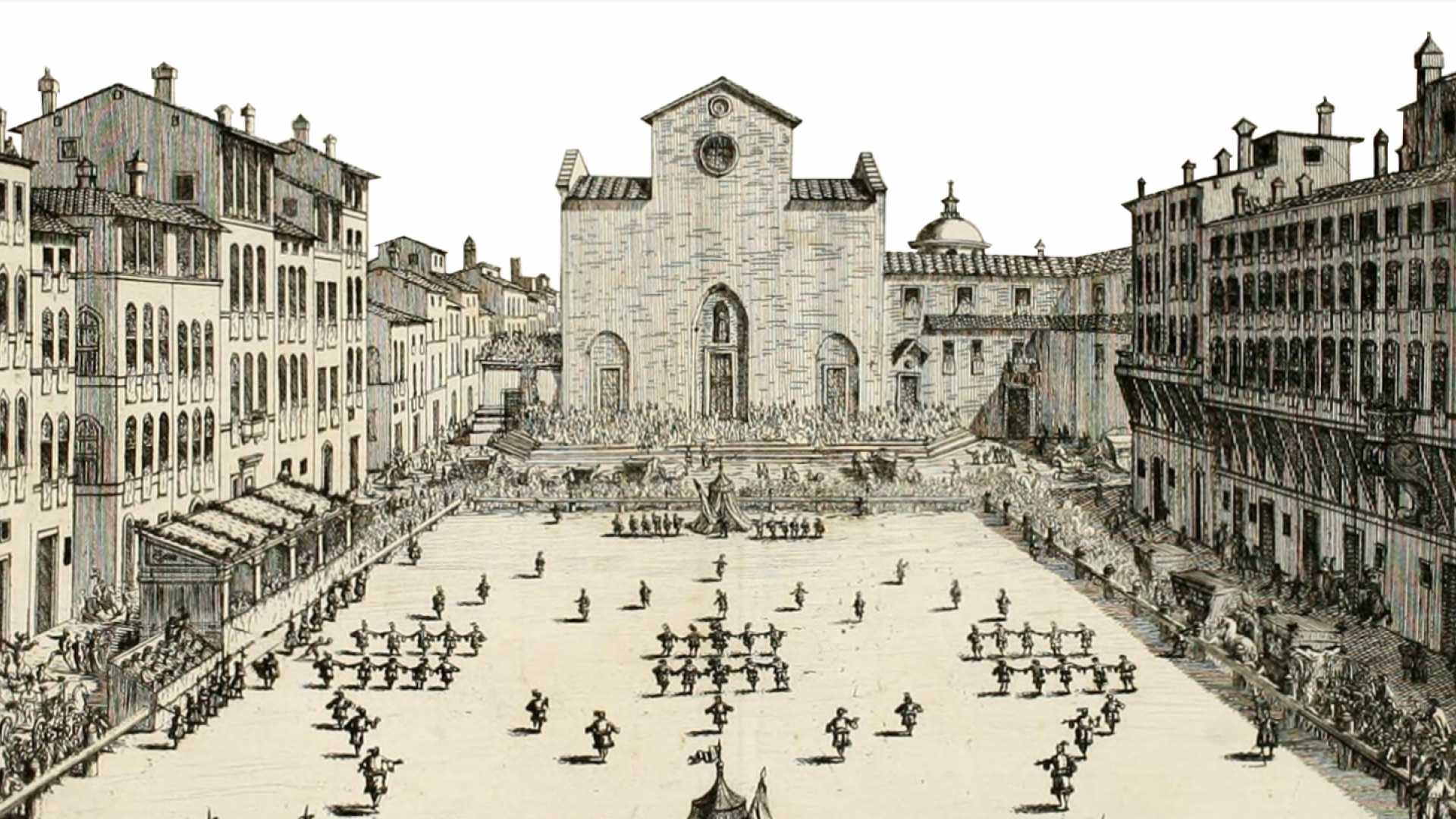

The first Calcio Storico on record took place in 1470, and by the end of the 1400s, the game was popular with young Florentines, who played pick-up matches on every street and square of the city. Public outrage over the unruliness led to regulations confining the game to specific piazzas, as well as signs reading “No ball games”, much like the ones you see around Florence today–though children seem to always be playing soccer against churches here anyway. Not just for the streets, Calcio Storico was a game of distinction, and many nobles, including members of the Medici family (future popes, no less!), played too. On some occasions, like the one in 1490, Calcio Storico was even played on the frozen Arno.

But the match that really established Calcio Storico’s legacy was that of 1530. Three years prior, the Florentines had rebelled against Medici rule, exiling the family and establishing Florence as a theocratic Republic. This didn’t sit well with the Holy Roman Emperor, and, in 1529, he laid siege to the city in an effort to reestablish the sovereignty of his political allies. On February 17th, the Florentine soldiers, guarding the walls of the city, left their posts to play a game of Calcio Storico in Piazza Santa Croce, the location most visible from the hills where the enemy was camped. It was a symbolic gesture, an affront meant to show disregard for the enemy and prove that the city’s spirit had not dampened–a message driven home by the musicians who played from the roof of the Basilica. Florence would eventually fall in August of that year, and Medici rule would be reinstated. But perhaps this story, and that of Calcio Storico, is emblematic of the spirit of Florence: a city that likes to believe it’s an underdog punching above its weight, a city that chooses David as its symbol, slayer of the giant Goliath. A city that supports Fiorentina, a soccer team which is good, but never quite good enough. Florence might not win, but it will always lose with pride.

The popularity of Calcio Storico waned over the following centuries, but in 1930, on the 400th anniversary of the Florentine siege, the game was revived under the initiative of Alessandro Pavolini, local leader of the National Fascist Party. With a mindset typical of other Fascist cultural projects, which sought to return Italy to its glorious past, Pavolini organized a reenactment of the legendary 1530 game in Piazza Santa Croce–the fact that the game is still played here is a call back to this match.

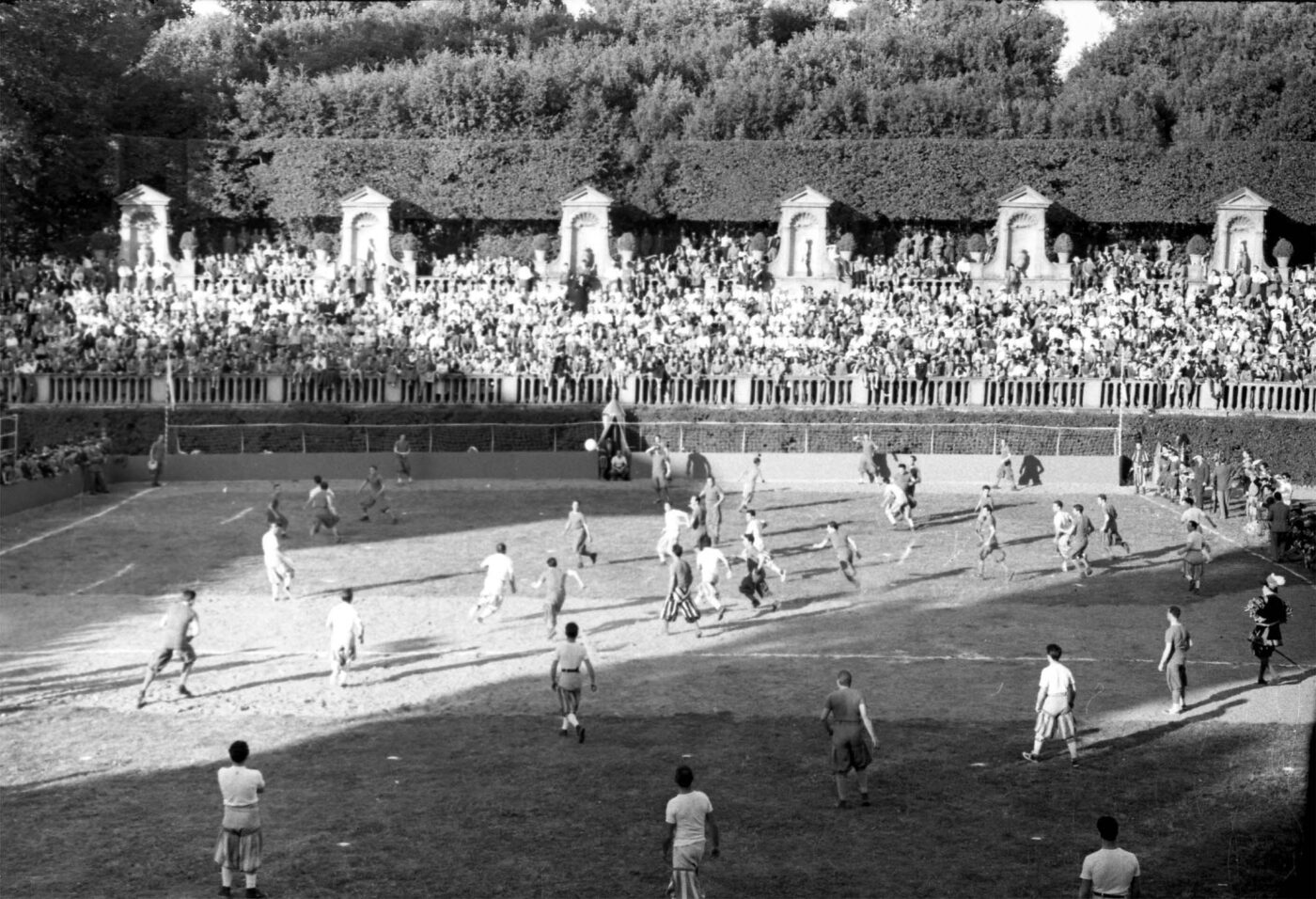

Calcio Storico in the Giardino di Boboli (1955). Courtesy of Foto Torrini.

THE BEHIND THE SCENES

A few days after the semi-final, I’m invited to the Verdi headquarters, a sporting complex in the northeastern district of Campo di Marte, by Sebastian Rodwell, one of the team’s top calcianti, a PE teacher, and a marketing consultant with a background in professional rugby. More than just the Verdi’s training grounds, the clubhouse hosts a retirement home, a gym, and a boxing society. Sebastian explains that the space is “about more than the green team. We’re in the heart of Campo di Marte, so we need to have a social function. We want to give something back to the community and be a reference point for more than just Calcio Storico.”

The setup does indeed lend itself to social functions: the kitchen, fireplace, TV, and walls, hung haphazardly with photos of players and past games, bring a cozy, almost familial atmosphere. And for Sebastian, it really is a second home: “In 2020, when my rugby club went bust, I didn’t have a place to stay anymore. I spoke to the president [of the Verdi], and he told me I could stay as long as I wanted. So I lived for a period of time in the clubhouse; it was a bit like being in Harry Potter.”

Like Sebastian was, most on the team are professional contact sports and rugby players, though others are club bouncers and trainers around Florence, and a few work office jobs. The calcianti are not paid, crucial to the game’s philosophy: players have a genuine bond with their color, motivated to play only for the sake of the game, the neighborhood, the history, and the thrill of the fight.

To be a player, you must be born in Florence or have been a resident for more than 10 years; when rules were introduced allowing up to three foreigners per team, they were quickly scrapped to keep the game deeply Florentine. But being a Calcio player requires a lot more than birthplace, or even physical ability. “You need time to become part of it. There’re a lot of little components that make you a calciante,” Sebastian says. “[You have to] come here three times a week, speak to the veterans, learn the history.” I’m reminded of what an American tourist at the game told me when I asked what made him choose to sit with the Verdi fans: “Someone told me the view from their bleachers was better.” As the game becomes more and more known outside these boot-shaped borders, many wonder about the future of the game and its fanbase. The tourist’s cries of “picchia!” certainly didn’t have as much weight behind them as those of the locals.

It’s because of Sebastian that I haven’t called Calcio Storico a sport. “It’s a game, a historical reenactment which honors the history of the city,” he tells me. “I don’t think you can call it a sport. It’s a brawl, a battle. You have rules, but sometimes those rules aren’t respected. In sports, sportsmanship follows different criteria. In Calcio Storico, you don’t have sportsmanship, but you can have respect.” He recounts a match from 2021 in which his teammate was brawling with an Azzurri player. The player’s mouthguard slipped out, and the Verdi player waited for him to put the safety gear back on before continuing the fight. “I get goosebumps thinking about it.” (He really did get goosebumps.)

In the early moments of this year’s semi-final, the Rossi score three caccie (goals) in quick succession. Players are getting body slammed left and right while the carriers casually toss the ball among themselves at the back, waiting for an opening. In the middle of the pitch, at least seven different fights are taking place: in these moments, it feels as if the ball is hardly important. Suddenly Sebastian finds a path, books it to the other end of the field, and snags one caccia back for the Verdi. Soon after, they score again. A red player is sent off the field for poor conduct, and it feels as if the scales are tipping in favor of Verdi. But only for a moment. The loudspeaker crackles: “Sebastian Rodwell espulso!” Caught for an illegal punch, Sebastian resignedly clambers over the fence and watches the rest of the game from the sidelines. The Rossi soon overwhelm the Verdi–7.5 to 2–and cement their place in the final.

“I definitely believe there is some form of respect towards the opponent, but, in the heat of the moment, sometimes it’s not a matter of not bringing respect. It’s just instinct; it’s survival,” Sebastian recalls. “I got knocked out 20 minutes into my debut in 2021. I had three people stop me, and a fourth kneed me really hard in the head. It was a baptism in fire. I don’t justify it, but I’m aware that it’s part of the game. You always know how you’re entering, but you don’t know how you’re gonna come out. But, for me, what happens on the battlefield stays on the battlefield.”