You likely know by now that food in Italy is a serious matter, almost a religion, but you may not have known that it’s serious to the extent that true cults exist across the country, dedicated not to saints but to cuisine. Seriously, here in Italy, there are fraternities devoted to worshiping specific recipes or ingredients, complete with initiation rites, oaths, and ceremonial attire. Academics of cod, brothers of polenta, devotees of ossobuco, and staunch defenders of the rotisserie; between revelry and preservation of national gastronomic heritage, food-obsessed confederations can be found from tip to toe.

One of the oldest is the Learned Brotherhood of Tortellini, established in Bologna in 1965, while the most famous is the Venerable Brotherhood of Baccalà alla Vicentina, based in Veneto, where new knights are initiated with a touch on the shoulders by a “sword” made of dried cod. There are dozens upon dozens, from the pizza fraternity to the one for hot cotechino, from organizations for bollito misto to factions in favor of Puglian focaccia–all dedicated to famous Italian dishes, or sometimes just to products practically unknown beyond their home provinces. There’s even an association, FICE (Italian Federation of Enogastronomic Circles), that brings them together at the national level.

Calabria has four: Bergamot in Reggio Calabria, Cod in Cosenza, Calabrian Frittola (a dish made from pork offal and rind) in San Fili, and The Ancient Congregation Tre Colli in Catanzaro, which venerates the morzello.

These hyper-local associations work to preserve a sense of belonging to their territory and recipes that risk disappearing with globalization. Robes, emblems, and banners may just be a playful facade for a commitment that unites professors and notables of each city and leads to conferences, events, and gatherings of historians, gastronomes, and chefs. In Reggio Calabria, a museum dedicated to bergamot has been established thanks to these efforts, and meetings with agronomists and institutions are fruitful. In the village of San Fili, activities for social inclusion and charity are organized around the frittola, while in Catanzaro, the morzello has become the symbol for the renaissance of local identity.

The morzello, or rather u morzeddhu catanzarisa, is exclusive to Calabria’s capital; you certainly won’t find elsewhere this stew of tripe, spleen, heart, lung, esophagus, concentrated tomato, spicy chili, salt, bay leaf, and oregano stuffed in a pitta, a typical local bread with the fluffiness of a focaccia and the shape of a bagel. With roots in working-class cuisine–offal were the only affordable cuts of meat–the morzello is often called the city’s “most illustrious” dish. Even if it’s a poverty-based concoction made of innards, it’s not slimy, but chewy and comfy thanks to the large amount of rich tomato sauce that drips from the bread.

The historic center of the 86,000-large Catanzaro was, until a few years ago, full of morzeddhari, who, in their characteristic putiche (taverns), started selling pitta sandwiches with morzello to factory workers, farmhands, and manual laborers at 10 AM, during their break from the tough hours of the workday.

If the “quinto quarto” (offal) has historically been scorned by the wealthier classes of society, over the years it has conquered the palate of an entire people to become the symbolic dish of Catanzaro. However, with economic prosperity over the postwar period, the putiche began to close, and the morzello started to fade from the city’s culinary habits. That is, until a fraternity decided to reverse the course of history by committing to its defense and valorization. With the cry of “in vino veritas in morzello salus” (“in wine, truth; in morzello, salvation”), they solemnly swear allegiance to the morzello, signing the pledge with a sauce-smeared chin on baker’s paper, that of pitta–for morzello “t’a dde sculara gargi gargi” (“must drip from your mouth”).

Morzello

It all began on December 28th, 1984, when four high school classmates gathered for the holidays in front of a plate of morzello. Year after year, the tradition grew, and the revelry gave way to a real association and an academy which teaches how to make morzello and educates on the stew’s history and economic potential. Today, the members count around 80, and being part of the congregation has become prestigious. Bringing together professionals, politicians, and high-ranking city officials as well as restaurateurs, the association admits new members every year on December 28th during an exclusive private event. Members wear red aprons embroidered with the symbolic eagle of Catanzaro, vote for their president, select new entries, and, of course, eat pots and pots of the famous dish.

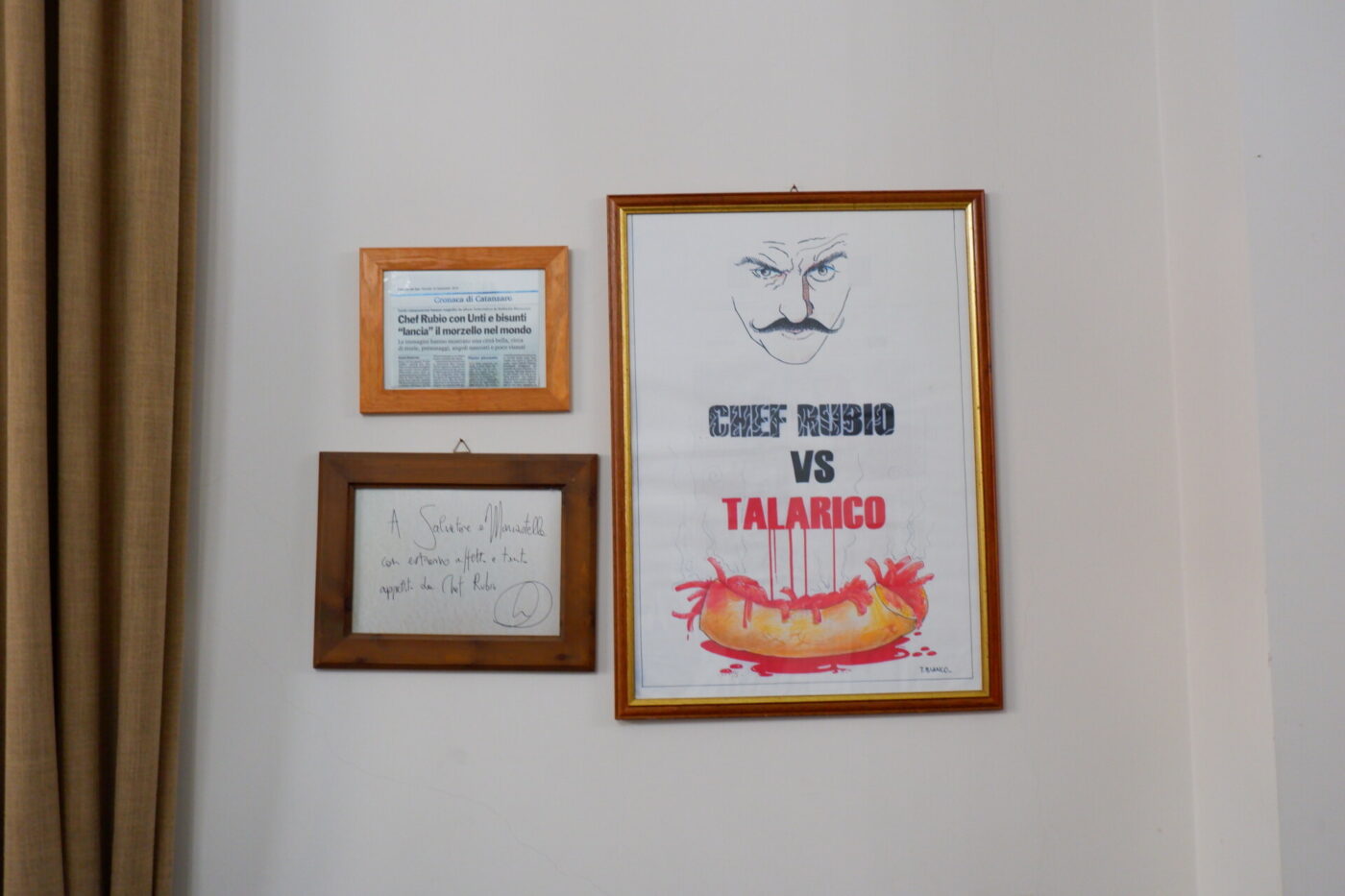

A place in the club is certainly in high demand, but it’s not just that: morzello has come back into fashion, trattorias have started making it again, and new places that offer the dish have sprung up throughout the city. In addition to the classic Trattoria Talarico, the last remaining historic putica (a must-visit for genre enthusiasts), Morzelleria de’ Baracchi, a morzello fast-food spot that offers variations on the theme, and Pizzeria Artigiana, where they stuff the stew inside a calzone, have opened. Signs advertising morzello have returned to the city, and, thanks to the association, Catanzaro can now brag of some TV appearances and a new influx of gastronomic tourism.

By the rallying cry of a congregation that has nothing ancient about it, Italians are discovering local traditions for the first time, and Calabrians are returning to eat their forgotten dishes. Exactly how it used to be? Not at all; it’s even better.