Once scarcely known outside of Puglia, now a veritable culinary celebrity, burrata soared to the top of restaurant menus around the globe after it was introduced into the LA food scene during the early 2010s. Despite its explosive international debut, a certain mystery cloaks this cheese’s origins. The story of burrata’s birth arises from Pugliese oral transmissions, with some dating the cheese back to the beginning of the 1900s, and others to the ultra-specific 1956. It is nevertheless agreed upon that burrata is a relatively new cheese, and one that has come a long way from the anonymity of its youth.

The legend goes that burrata, like most good things, was invented by accident. Its alleged creator was a dairy farmer named Lorenzo Bianchino, from Andria, Puglia; a little stone town north of Bari nestled amidst olive groves, almond orchards, and vineyards. The heavy snowfall one February day (a rare occurrence in balmy Puglia) meant that Lorenzo was unable to travel to the local market to sell his fresh milk and mozzarella. Not wanting the by-products of the cheese to spoil, he decided to combine the curd, left-over ritagli (scraps) of mozzarella, and the cream from the top layer of the morning milking. Burrata was born, its name literally meaning “buttered” for its mild, creamy flavor.

This was an innovative way to reduce waste, and the method was picked up by neighboring dairy farms over the following decades. The production process is not as effortless as Lorenzo’s improvised alchemy makes it sound, and rigorous guidelines must be followed for the cheese to qualify as burrata. The cow milk is curdled, dropped in hot whey, and carefully cut with a metal implement nicknamed “cestino” by the Pugliese. It is then stirred, pulled, and kneaded into an elastic consistency, a technique known as pasta filata, meaning “spun paste”. (Puglia is home to a range of pasta filata cheeses: provola, mozzarella, and caciocavallo are just a few).

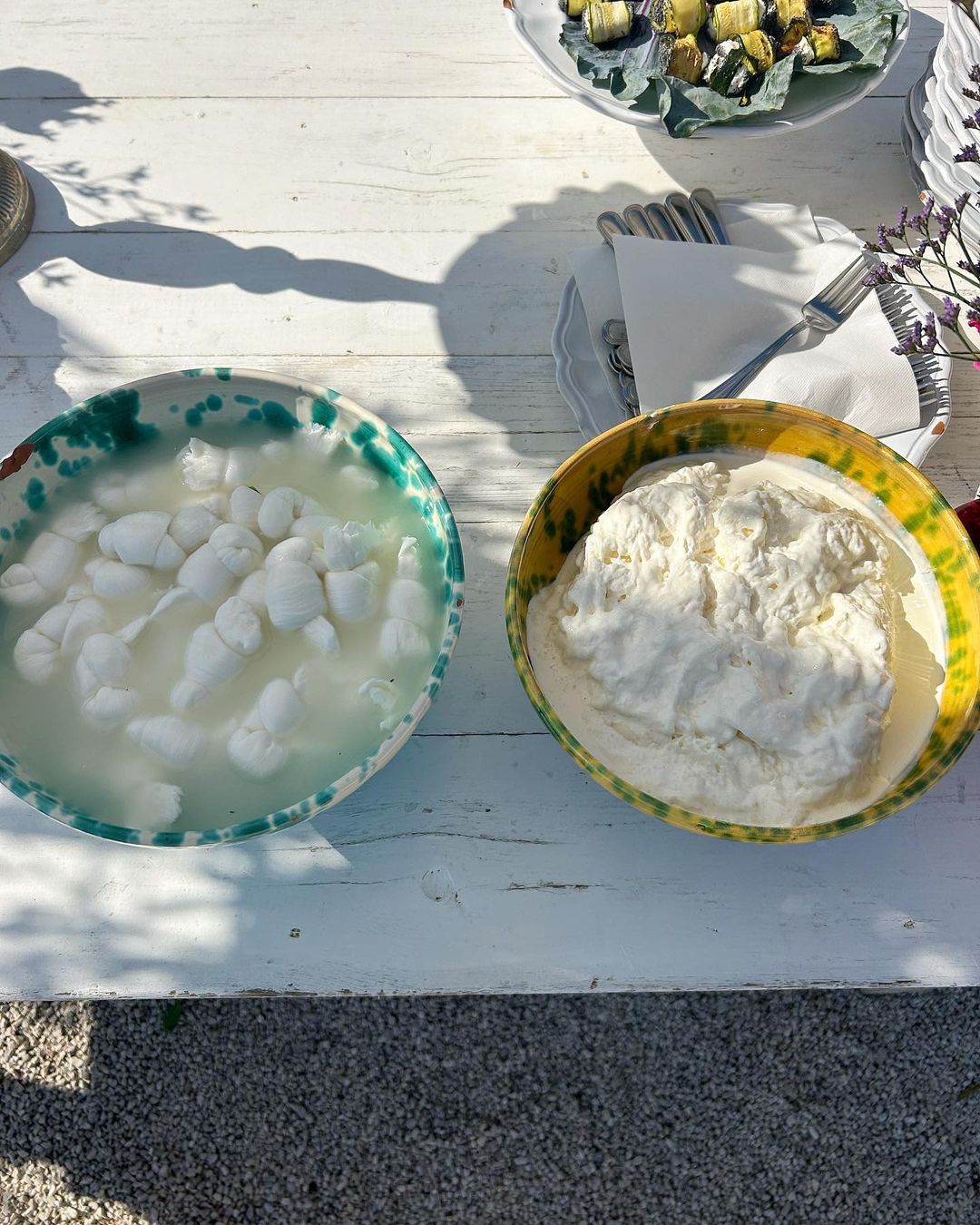

This becomes the outer casing of the burrata, and, in Lorenzo’s day, it was blown into shape to create a hollow receptacle. The sfilacetti, or the leftover scraps of the curd, are salted and mixed with cream to make stracciatella, so called because the curd is torn (stracciata) by hand. The stracciatella is placed inside the hollow pouch, which is tied like a balloon and either packaged or plonked ceremoniously onto an expectant plate.

Traditionally, the cheese would be wrapped in the green leaves of the asphodel plants that grew in thick clusters over the surrounding countryside. The leaves preserved the cheese, but were also an indicator of freshness: bright, waxy leaves meant the cheese was ready to eat, yellowing leaves meant it was a few days old. This came in handy in an era before printed expiry dates, as burrata is traditionally supposed to be eaten on the same day it’s made, when its texture and flavor are its freshest. Not nearly as charming as local foliage, you will now find the cheese sheathed in plastic or preserved in salt brine, thanks to which it can be exported from the farms of Puglia and on to the shelves of international supermarkets.

Courtesy of Masseria Potenti

Despite its origin story of waste reduction and resourcefulness, burrata’s short shelf life and laborious production process meant that it quickly became seen as a luxury product: a cheese for Puglia’s rich. For much of the 20th century, burrata was barely known outside of its native region. The cheese first made its way to foreign shores due to demand from Southern Italian diasporas, arriving in the United States in the late 1900s to be predominantly consumed by New York’s Italian American community. Cheesemaker Mimmo Bruno is credited to have made the first burrata stateside, a bid to recreate the flavors of his childhood in Puglia. The product was initially overlooked by restaurant owners and chefs, who thought it wouldn’t sell amongst an American customer base. Nancy Silverton, chef at Los Angeles’ Campanile, took the risk, and put the cheese on her menu as part of a sandwich. Fast forward a decade of rising recognition, and the rest is history. (Silverton’s restaurant Osteria Mozza in LA now boasts a “burrata bar”.)

While a global appreciation for the regional artisan product may seem like a good thing, burrata’s bloated fame means it has long lost the simplicity of its origins. The Pugliese eat it al naturale, garnished with little besides a drizzle of oil, a pinch of salt, and a side of crispy fresh bread. A far cry from how it’s often served today, part of hyper-Italian concoctions that plonk four balls on top of one pizza, mix it into pasta… the list goes on. Italian restaurant Cinque, in Dubai, even serves it covered in edible 22-carat gold leaf. Now a predictable starter splattered across restaurant menus–smothered in edible metal, topped with truffle shavings, and dolloped on a plate along with a hefty price tag–food critics and consumers alike have condemned this cheese to be Old News.

An unfair fate for it, at least to my mind. Burrata is officially a long way from home, having been plucked from its earthy roots and launched into a glitzy world of trend-driven restaurant culture. But in Puglia, the cheese tells a different story. There, if you find the chance to stretch into a chair under the afternoon sun, you can cut into a burrata that was made that morning from the cows that graze sleepily nearby. Away from the clatter and buzz of culinary sensationalism, the cheese will taste as fresh as the winter day on which it was created. Here, farmers still pick the waxy leaves of the asphodel plants, and wrap them carefully around its skin.

Photography by Food Feels

WHERE TO FIND THE BEST BURRATA IN PUGLIA:

Caseificio Olanda – Established in 1988 in Andria by Michele Olanda and his wife Carmela, this family-run dairy farm is nestled between the hills of Alta Murgia and the Castel del Monte. If you’re looking to delve into the history behind their excellent burrata, have a tour of their Museo del Latte, which ends with a cheese tasting (what else?).

Caseificio Dicecca – This family-run dairy farm was founded by Vito Dicecca, who first began helping his father make cheese when he was just 9 years old. His trendy take on tradition makes this newer caseificio, located in Altamura, Murge, one to watch. If you’re looking for something completely off the beaten track, check out their Baby Dicecca offshoot, a small wooden kiosk in the Mercadante forest that offers cheese tastings alongside local wine and delicacies.

Caseificio Artigiana – Caseificio Artigiana started out as a five-person operation in an abandoned factory in Putignano. Fast forward 20 years or so, and the dairy farm’s burrata has won a flurry of international awards. Also of note are its range of Pugliese cheeses, such as the caciocavallo affinato in grotta, an ancient tradition of cave-aged caciocavallo passed down by Pugliese farmers.

Caseificio Fratelli Fucci – The clue is in the name; this dairy farm too is a family business, established and run by the Fuccis, born and bred Andrian locals. The caseificio is committed to carrying on the town’s burrata legacy, and is renowned for its fresh fior di latte cheeses.

Beyond burrata, Puglia is the land of latticini. Head to Caseficio Aziendale Lamapecora for a 7th-generation dairy farm celebrated for its ricotta. If caciocavallo is more your thing, you have a wealth of options across the region, from Caseificio Stella Dicecca and Caseificio Levante in Altamura to Casa del Latticino in Acquaviva and Riccardi Nicola in Gravina di Puglia. Keen to branch out beyond cow’s milk options? Peppino Simeone in Monti Di Basile Martina Franca is renowned for its goat milk cheeses.