Puglia is a region of Italy quick to be reduced to its postcard images–a conical, limestone trullo of Alberobello here, Polignano a Mare’s glimmering cove there, an area that fits neatly into a certain idea of a rustic Italian lifestyle, a portal to the past.

But Puglia has not literally been frozen in time, as much as tourists might prefer to believe. Whether it’s the landscape, the characteristic hospitality of the Pugliesi, or even the region’s disparate economic development (and relative economic precarity compared to other parts of Italy) that has created this situation, Puglia is also home to something perhaps less known: a large creative and artistic population.

Part of this is built into the very fabric of the region’s traditions. According to the Regione Puglia’s department of economic development, innovation, education, training, and work, this pocket of beauty in southern Italy fosters the creation of some of the country’s most typical artisan items, like ceramics, cartapesta (papier-mâché), musical instruments, embroidery, and mosaics. In Grottaglie, known as the ceramic district of Puglia and located in the province of Taranto, artisans painstakingly craft plates and vases, sometimes adorned with abstract faces or formed in the shape of everyday objects like wrenches and highlighters. The Pugliesi are inventive even in this way, not limiting themselves to one fixed idea of what art means. As the region’s website notes: “Even the poorest materials can become art.” The traditional “pupi,” the cartapesta-made figurines that often bedeck Italy’s characteristic nativity scenes, are “one of the most creative and representative expressions of the region,” per Puglia’s regional government.

But the region’s artistic sector is more than the sum of its traditions. Economic data from 2013 puts the total number of businesses in Puglia’s artistic and traditional artisanship sector at more than 74,000. The value of Puglia’s global exports totaled 41 million euro in 2013, up 17% from 2012 numbers.

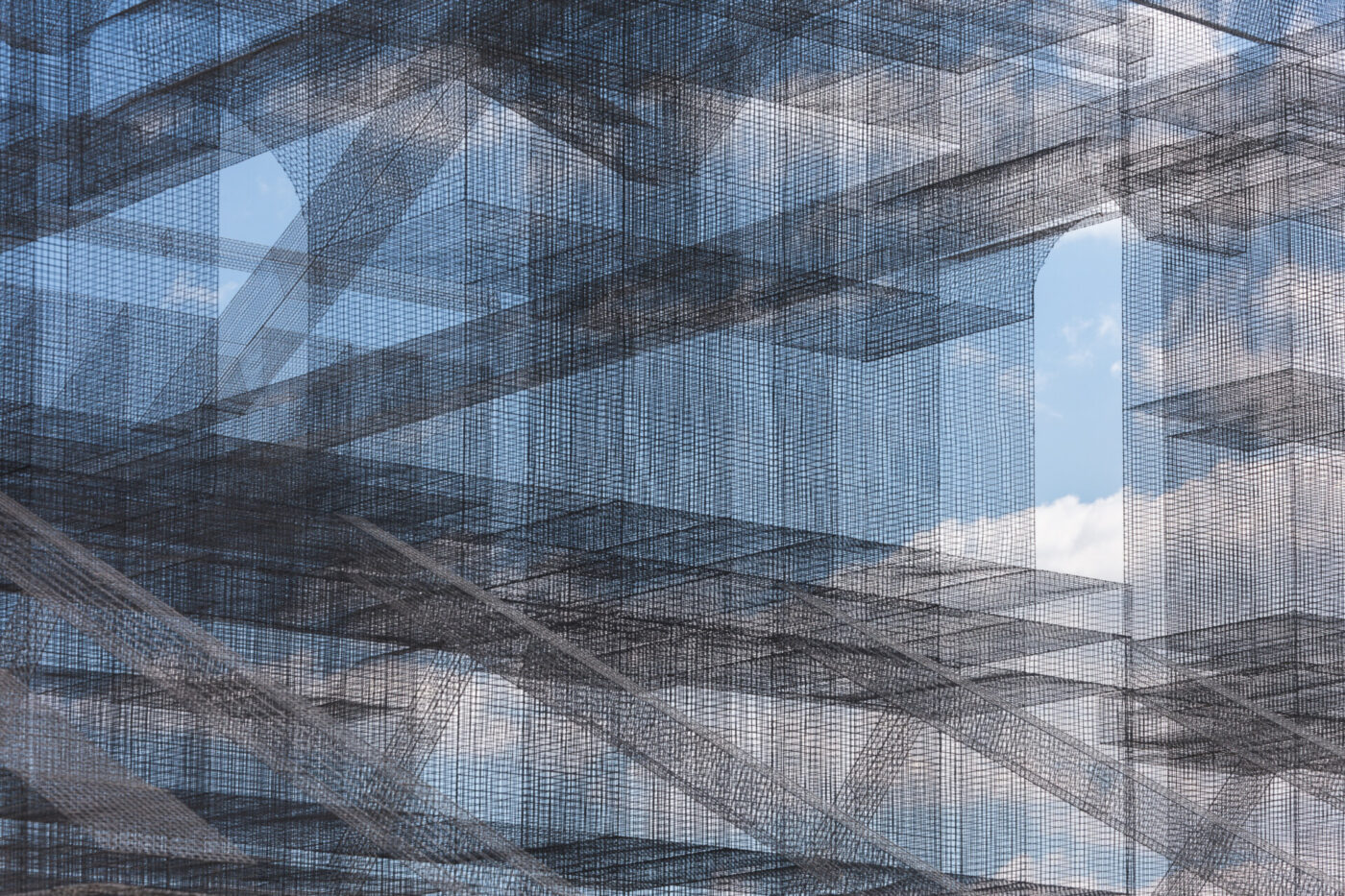

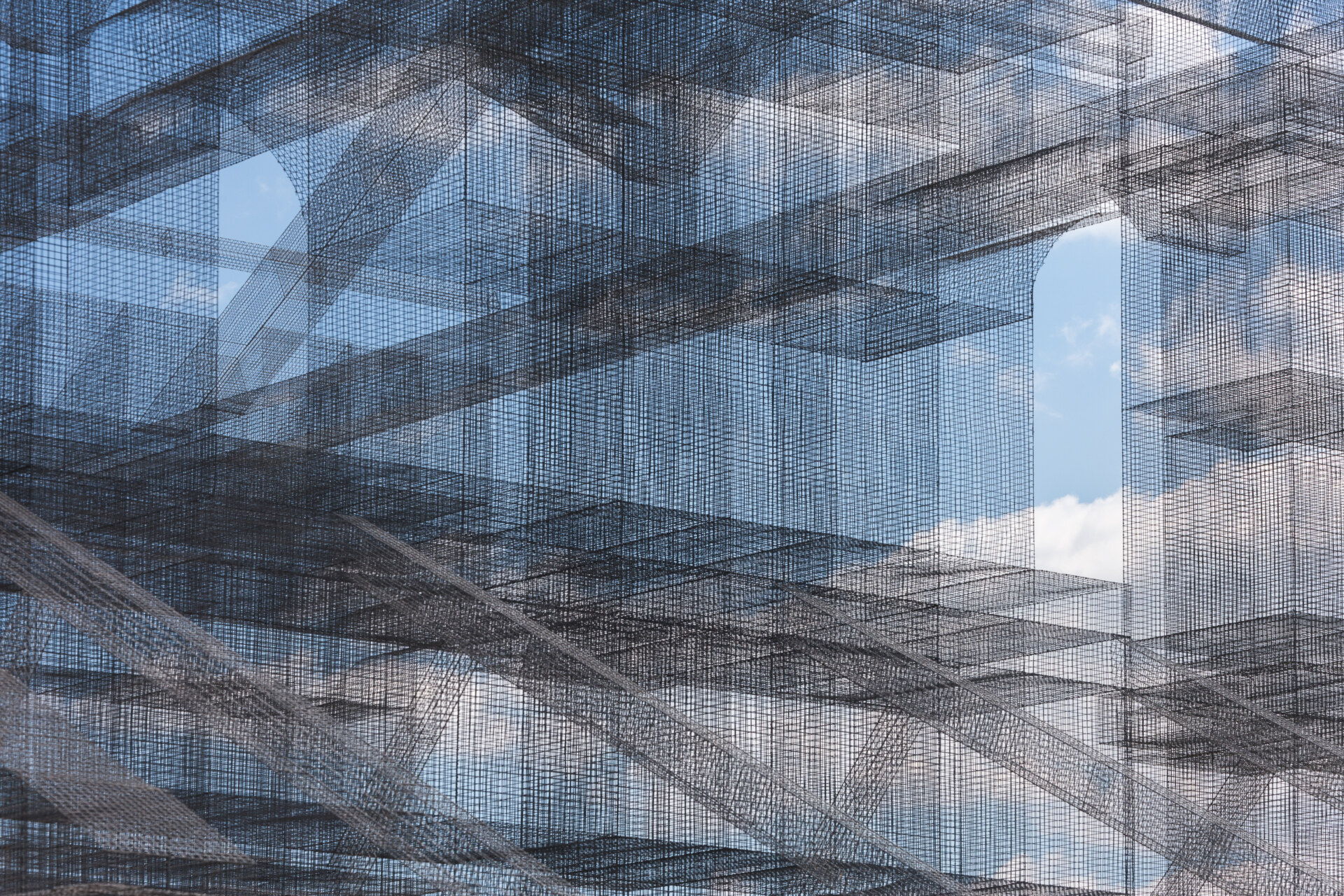

More recent data was not available on the region of Puglia’s site, though anyone who has visited Puglia in recent years can tangibly see the region’s artistic growth. Taranto and Lecce have both emerged as creative centers in the area, in fields like design and architecture. The region as a whole has become a showcase of eclectic, modern architecture that draws on local traditions while, in some ways, subverting them. Contemporary art centers like Bari’s Spazio Murat and artist Edoardo Tresoldi’s installation at the archaeological park of Siponto offer evidence of this.

Photography by Roberto Conte, Courtesy of Edoardo Tresoldi

Economic data backs up this anecdotal phenomena. Membership association Distretto Produttivo Puglia Creativa represents roughly 13,000 businesses and around 58,000 employees, ranging from performance to design, per a recent interview with the district’s president, Vincenzo Bellini. Recent numbers from the organization indicate that the industry produces 2.5 billion euro in annual revenue, making up about 4.4% of the region’s gross domestic product.

But based on interviews with two Pugliesi artisans who largely sell their wares online, the creative market in Puglia is both on its way up–and still in need of some growth. Teresa D’Ambrosio, who was born in the province of Bari, designs her characteristic jewelry pieces with actual flowers, like dandelions or forget-me-nots, sometimes collected by D’Ambrosio herself from the grounds of the region. Pressed and dried into resin, her BeFloral Etsy shop is full of vibrant designs that resemble a tiny garden in an earring or friendship bracelet. She’s recently started a new offshoot of her business, in which she crafts pictures–upon request–using the dried flowers from a couple’s recent wedding bouquet.

D’Ambrosio’s passion for art started at a young age, when she was busy creating bamboline, little dolls, for children or braided bracelets made of wool.

“I always had the inclination to work with my hands,” she said.

Courtesy of Teresa D'Ambrosio

But her path to working with dried flowers was circuitous, to say the least. It began in the most digital of ways, by watching an online tutorial from a Japanese artist who worked with flowers and jewelry. D’Ambrosio, in her own words, fell in love with the form and decided she would teach herself.

“It was a disaster at first,” she said. “But obviously, practice and experience is the only solution. In the end, this was how I started, and there was an evolution with the jewelry becoming more precise.”

While D’Ambrosio’s Etsy page lists its opening date as 2015, she shrugs that off as the real business opening. Instead, there was an almost-sudden boom roughly four years ago, around the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when a near-global lockdown pushed shoppers online.

While many of her clients come from the United States or France, she sees the benefit of being able to manage everything from her in-home studio, where she can stay connected to her local family and her heritage. But the priorities of the typical Pugliese, perhaps compared with the average Italian, has had an impact on her business.

The region is a study in contrasts–its lush and, in many ways, wild beauty makes it a popular destination for tourists, but its relative lack of infrastructure and emphasis on the hospitality industry make it a hard place to create a life for a young person. While Italy’s post-graduate employment rate as a whole is 62.8%, in Puglia, that number is only 37.1%, per a 2021 report from MEDUSA, a European Union-funded organization dedicated to promoting sustainable adventure tourism in the Mediterranean. And while Puglia has a road network, its railway infrastructure is 20% less developed than the Italian average. The region’s more than 4 million people are densely concentrated in its cities, with roughly 64% of people living in 20% of the area’s cities. And for the people who do choose to remain in Puglia, nearly 36% of the region’s enterprises–and 1 in 12 people–are concentrated in the tourism sector.

“In my opinion, Puglia is a conglomeration of artists–we are all a little bit artistic, influenced by the sea and the beautiful climate,” D’Ambrosio said. “But the typical Pugliese is not very accustomed to buying artisanal objects–it takes a little bit of education. It’s also an economic issue. Artisanal goods have a cost, and we are not very used to spending certain amounts of money on artisanal products.”

A 2023 study from the National Institute of Statistics found that not only did Italians have a lower economic and physical well-being relative to the European Union’s average, but that Puglia ranked even lower. This finding was evaluated in part based on factors related to education and training, work, life expectations, and health.

“If in Italy, things are going badly,” wrote Giuseppe Andriani of the Quotidiano di Puglia, “in Puglia, things are going really badly.”

And yet: so many have chosen to stay. In D’Ambrosio’s case, the region is “irreplaceable”. She loves to travel, but at the end of every trip, she finds herself imbued with the desire to return home, perhaps to the trademark landscapes that have formed her youth.

Courtesy of Daniela Vitelli

She is not alone in that sentiment. Her friend and fellow artist, Daniela Vitelli, was born in Bari and has never left the province in which she was born. From the quality of life to the quality of food, Vitelli has always considered herself more than satisfied living in Puglia.

As an artist, she has distinguished herself from the rest by using a little-known Renaissance-era technique called “quilling”. Although the art form may have originated as early as Ancient Egypt, according to Corina Dragan Quilling Art, the style rose to fame in Italy and France when monks and nuns used strips of gilded paper to decorate the covers of religious books, relics, and icons. The look is achieved by rolling these strips into tiny shapes and putting them together to form an entirely new design. Vitelli’s designs range from constellations and anatomically-correct hearts to commissioned family portraits.

When she first started out, she was working not with portraits, but with jewelry. In fact, it was only after tiring of quilling accessories that she decided to try something larger and more distinct. From there, her business grew.

“The fact that there were requests pushed me to continue,” she said. “It became something new, and I find that where I live also motivates me–there’s always sun and there’s more socialization.”

It’s because of this that Vitelli is not surprised Puglia has become the creative capital it has. She lists the sea, the climate, and the food as possible reasons, recalling stories of those who have left Puglia for work only to eventually return. There’s something that calls people back.

And yet: there is always an “and yet.” Puglia’s economic tenuousness is a lived experience for Vitelli, who, despite managing both an Etsy shop and an active Instagram page, still works a day job as a social media manager. She longs for a future in which people understand all of the work that goes into handmade, artisanal products.

“Our work is not only by hand, but also by our intellect,” she told me. “We have to think about what we’re doing and the fact that we have studied–surely what we create is the product of our experimentation.”