It’s nearing 1 PM, and I’m perched outside a cafe watching people come and go. Tricolor bunting–green, white, and red–sways in the breeze, and comforting wafts of cheese-laden pizzette drift out intermittently from the kitchen. “E la famiglia? Tutto bene?” (“And the family, all good?”) an elderly woman inquires to the man behind the counter, before shuffling away on her walking frame, calling out “arrivederci!” behind her. It’s a familiar scene. Unremarkable, perhaps. A prosaic tableau that can be found in piazzas from Milan to Bari on any given day of the week. Except, it’s not Milan, nor Bari. No, today I’m in Bedford, a quiet market town an hour north of London, wrapped in a colpa d’aria-defying duvet coat as the temperature drops to zero.

You see, Bedford, it turns out, is the most Italian place in Britain. Not that you’d know it at first glance. The unassuming town is replete with the usual hallmarks of British town centers–greasy spoons, dim-lit pubs, and roller-shutter-ed shopfronts plastered in wonky “to let” signs–more “fish n’ chips” than Fellini. Still, Befordino (as it’s affectionately termed by certain locals) is as much of a geopolitical curiosity as the Lederhosen-clad colonies of the Peruvian Amazon, or the Windy City’s unexpectedly large Lithuanian community. Here you’ll find a staggering 14,000 families of Italian descent, one fifth of the town’s total population. A closer look around confirms this–there’s an Italian church, Italian Vice-Consulate, and an Italian social club. There’s a local radio programme, a yearly festival celebrating Italian culture, and, as I discover while flitting my way around the town’s many Italian coffee shops, it’s not uncommon to hear conversations slip from English to Sicilian, either, or spot bumper stickers slapped on cars pledging allegiance to Serie A soccer clubs.

But to understand why, let’s rewind. Back to 1951, precisely, when unemployment was a plague upon Italy, especially among the agrarian South. Local historian Carmela Semeraro, who moved from Puglia to Bedford as a teenager, noted that, “The south was grossly underdeveloped and overpopulated… The Italian Government was at a loss as to how to solve the immediate problem.” At the same time, Britain was in dire need of an increased workforce to rebuild her towns and cities after World War II, and so an agreement was made based on the countries’ aligned interests, with bulk recruitment schemes set up across the UK. In Bedford specifically, most were employed by London Brick Company, who set up offices in Naples where young men were medically assessed, selected, and sent to the UK in search of a better, or at least more prosperous, life.

Men came from villages all over Sicily, Puglia, Campania, Abruzzo, and Calabria, on lucrative four-year contracts, though they were often met with conditions worse than the ones they had left. Working in the factory was very different to working in the fields, and cramped hostels exacerbated the long, unsociable hours. Michaelangelo Scrocca was one of them: “We were not used to the English food that was served. I was there for forty days. I lost so much weight…” he told Semeraro, who also founded Bedford’s Club Prima Generazione Italiani, a social space for those first generation migrants. It was here where she produced an oral history of their experiences, later published in her book Hidden Voices, Voci Nascoste.

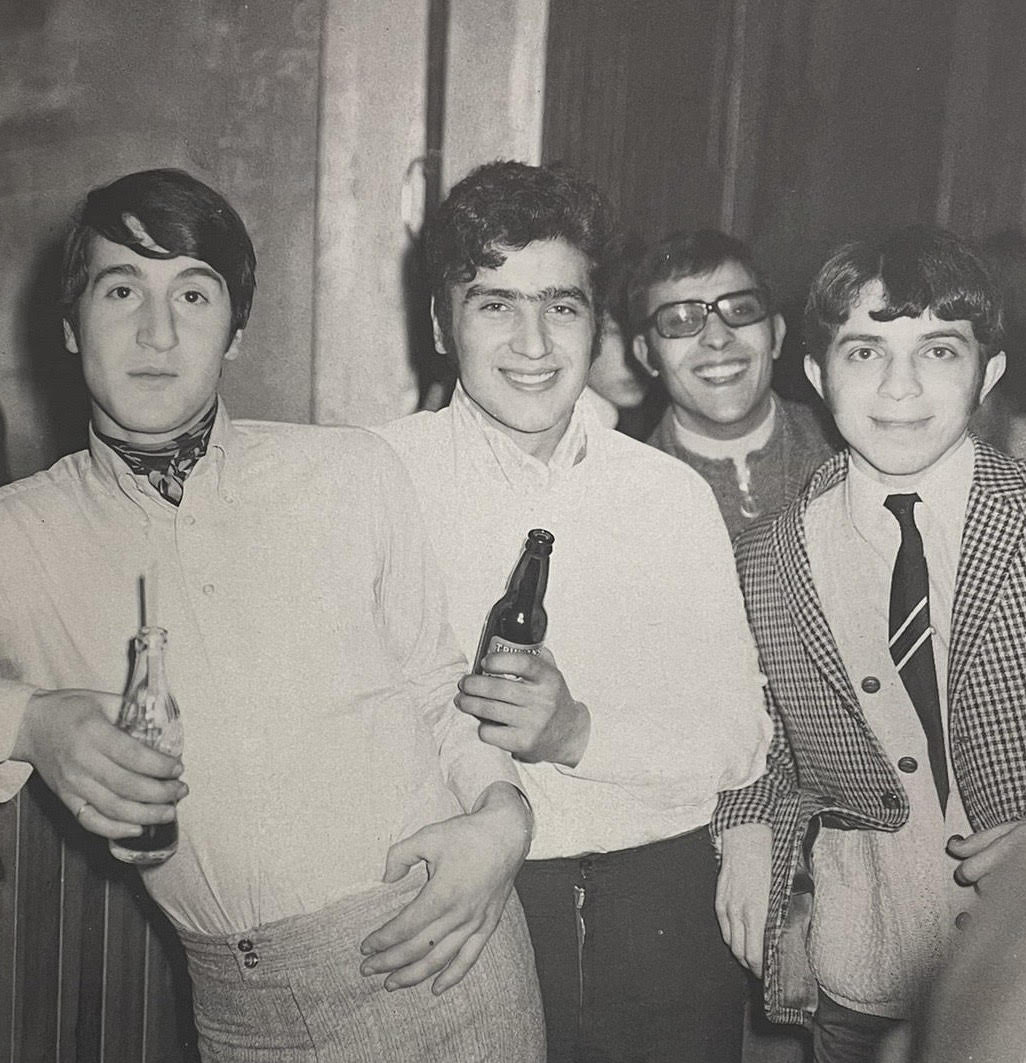

Bedford Italian youth club in the 1960s; Photo by La Voce

In the decade succeeding 1951, over 7,500 men had been recruited. Many eventually brought their wives and children over and remained in Bedford long after their contracts expired. Looking back on his decision to remain in the UK, Liberato Iaciofano, another member of Club Prima Generazioni, explained, “I don’t know if it was the right decision to remain here. We could have gone back to Italy after a little while, but there was always a fear that things would not have gone well. We felt more secure here.” Others, however, did return home, citing redundancy and–no surprises here–the British climate as two main reasons. But there were other contributing factors, too, cultural differences that some felt were too wide to bridge.

For Mr. Zenna of Caserta, it was a fear that his children would become independent from their family, as English boys and girls typically were, which spurred his return. Family unity has always been a mainstay of Italian cultural identity, and the continuous cultivation of close familial bonds is one way that Italians in Bedford have maintained an attachment to their roots. This is true for Daniela De Spirito, whose grandparents moved to Bedford in the 1950s, and passed down their culture through familial rituals, especially around food. “We eat a lot of Italian food, especially on Sundays. On Christmas Eve and Good Friday we eat fish, and we make lots of traditional Italian recipes around the holidays too.”

But the differences between her own generation and that of her grandparents are stark. “They only really socialized with other Italians, and didn’t understand English very well,” she told me, an account that rings true for many first generation migrants, who lived in a bubble quite apart from English cultural life. And yet, even this came with its challenges, given the diversity of the Italian population who came from all over the south, each with their own dialects, their own traditions. What they did share was religion, and in 1965, the Fathers Scalabrini founded Santa Francesca Cabrini, an Italian church named after Mother Francesca, the patron saint of immigrants. The church, with its modernist façade, is one of the first places I passed on my journey into Bedford, and was once a major area of Italian presence. Today, it seems like just another residential street, but through a car park just around the corner, you’ll find Club Italia, probably the only place in the country where you can pair a gelato with your pint–and when it comes to migration, isn’t that the ideal? To take the best parts of one’s native and adopted cultures and make life a hybrid of their best bits?

"Miss Italia" (formerly "Miss Emigrante") in Bedford, 1989; Photo by La Voce

Migration is an instance through which one is forced into a new reality; this reality changes those it encounters, and is changed by them, in return. But navigating those changes is not always as rosy as gelato and beer, and oftentimes leaves those experiencing them feeling stranded and displaced. “The second generation my parents were part of had it the hardest in regards to navigating the two cultures,” Daniela explains. This is a widely-reported experience for second and third generation migrants across the globe, the struggle of recognition, not just in their new home, but their old one as well. “I personally found it difficult to fit in,” she continues, “In Italy we were perceived as ‘inglese’ and in England as ‘Italians’. I would say the only other people that understand our lives are the other Italians in Bedford with the same experiences. I would identify as a ‘Bedford Italian’.”

With every passing generation, this new “third” identity flourishes. Where the first generations asserted a control which admitted few gaps for anglicisation to creep in, inevitably, over time it did. “Since my nonni passed away,” Daniela continues, “we don’t really speak Italian at home anymore. We still practice Catholicism, and the younger generation have also been baptized, but they don’t speak or understand Italian. I feel like with each generation it’s getting lost.”

But one area where allegiances remain particularly strong is on the football field. When England played Italy in the Euro finals back in 2021, the town’s Italian establishments were chock-full of die-hard Azzurri. “I don’t know any Bedford Italians who support England,” Daniela added. And although sporting occasions of this sort have not always passed peacefully–with clashes between sides documented from the 60s right up until the 2010s–it seems, from where I’m sitting at least, all rather genial. Returning to La Piazza for my final coffee of the day, I notice alongside the picture menus advertising mortadella and provolone panini, Juventus memorabilia and Ferrari pendants, an England scarf hanging neatly, its three lions bared for all to see.

Photo courtesy of Foods of Italy

Where to Eat and Drink like an Italian in Bedford:

La Piazza – Run by “local celeb” Libby Lionetti and his son, Joseph, La Piazza is a kiosk-style cafe bringing a slice of Italian campo culture to the UK.

La Rondine – This small bakery is Bedford’s oldest, and was started by Foggia native Salvatore Garganese who moved to the city in the 60s. Rumor has it they make the best sfogliatelle in town.

Mamma Concetta – A family-run restaurant specializing in Neapolitan-style wood-fired pizza and typical Italian dishes made with locally-sourced produce.

Foods of Italy – A one-stop shop for la spesa Italiana with a range of imported products from panettone to amari.

Pizzeria Santaniello – Another spot for authentic Neapolitan pizza, and the first Italian restaurant to open in Bedford.

Paninoteca – A great option for lunchtime, serving artisan sandwiches made from Italian ingredients with views over the River Great Ouse.