Bagnoli, the westernmost quartiere of Naples, lies trapped between the Bay of Pozzuoli and the hill of Posillipo–a thin strip hugging the sea with a view towards the islands of Nisida, Ischia, and Procida. It may sound idyllic on paper, but it takes just a short walk along the coast to understand that this is a place haunted by the blight of abandoned industries. Bagnoli is the site of what used to be one of the largest steel mills operating in Italy throughout the 20th century, a metal monster larger than the neighborhood itself.

Since 1992, the factory has existed as an abandoned husk, casting a shadow of pollution and economic malaise on the entire 20,000-large suburban neighborhood. Residual pollution levels are so high that it’s forbidden to swim in the sea, even when the air shimmers with the heat exuding from the cement. It’s small consolation that the beach is accessible: beach-goers aren’t even allowed to dig a hole to erect an umbrella, for the sand too is toxic.

“We all imagine Naples as the postcard of the gulf, with Vesuvius in the background. When you’re in the center of Naples, Bagnoli doesn’t exist; it hides behind the hill of Posillipo. It’s just a place you’ve heard about,” says Raffaele Vaccaro, a marine biologist who has just wrapped up production on a new docufilm about the area called Flegrea – Un Futuro per Bagnoli (Flegrea – A Future for Bagnoli), in which the actors are not professionals, but Bagnoli locals. “We want to tell the perspective of the Bagnoli citizen, saying ‘okay, we are here too, we live in this place, and we want to direct this attempt to imagine a future.’”

When casting began, the production team was shocked at the Bagnoli youth’s lack of awareness about the situation on the ground. “They had reached the point of not even asking questions anymore,” Vaccaro tells me. “This is a defense mechanism that develops in devastated territories, a normalization of something dramatic and terrible.”

Photo by Dimitri D’Ippolito

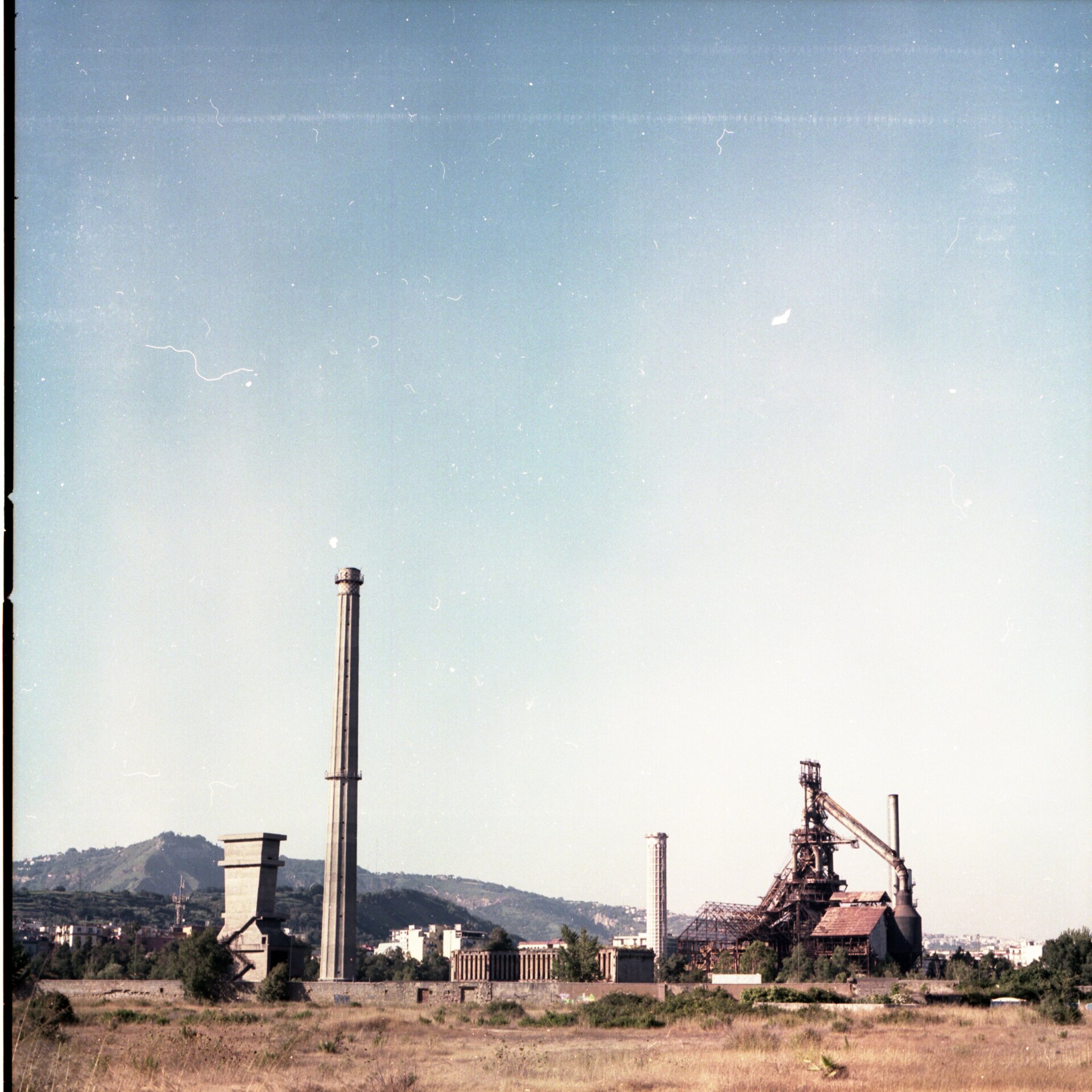

Industry in Bagnoli took off in 1911 with the opening of a steel mill for Italsider, Italy’s state-owned steel company, one of the largest in Europe at the time. This vast complex came to occupy two square kilometers of Bagnoli and, at its height, employed 8,000 workers–just over 25% of Bagnoli’s population. It wasn’t just the inhabitants of Bagnoli, but also those of Posillipo, home to some of Naples’s most luxurious and prestigious residences, who had to close their windows when the toxic cloud came knocking. “On one side, the most beautiful area of the city, the stunning hill of Posillipo,” asserts Stefano Romano, the Bagnoli-born director of Flegrea. “Then you turn a promontory and you have a factory which discharges industrial waste into the sea. It was designed all wrong from the start.”

Vaccaro tells me that Campania lacks a proper registry on tumors “but there are hundreds of anecdotal stories of former Italsider workers who died from diseases caused by air pollution.” He continues, “There’s always this contrast between work and health. We are ready to sacrifice our health and that of our families in order to work, accepting the destruction of our surrounding environment.” Indeed, steel was (and still is) the backbone of modern industry, the stuff that carried Italy through world wars and economic miracles, and so Italsider kept pumping out materials until 1992, when production became unsustainable–not environmentally, but economically. The rapidly globalizing market of the late 20th century meant that it became cheaper to buy raw goods from emerging countries such as China and India, to whom large parts of the dismantled industrial complexes were sold to.

Other factories operating in the Bagnoli area during the 20th century included Cementir, a cement manufacturer, and Eternit, which produced asbestos. Just this year, one of the major shareholders of the latter, Stephan Schmidheiny, was sentenced to 12 years in prison for aggravated manslaughter after being found guilty of hundreds of deaths by negligent exposure.

All this was happening on the doorstep of the largest city in southern Italy.

Bagnoli with Cementir and Italsider plants

Since the closing of the steel mill in 1992, efforts have been made by local and national governments to redevelop the area, with the two most notable examples meeting dramatic fates. The City of Science, opened in 1996, was, at the time, a state-of-the-art space featuring, amongst other facilities, a business incubator, an educational garden, and a museum called the Science Centre, which became a field trip destination for many schools in the Italian mezzogiorno. But, in 2013, a fire devastated four of the six buildings, including all of the museum space. The cause was identified as arson–though, as of this writing, the culprit has not been found. In the last decade, plans for the museum to be rebuilt call for it to be moved inland, impossible until the heavily polluted soil there is cleaned up.

Perhaps even more emblematic of the corruption and misfortune infiltrating the revitalization of Bagnoli is the case of the Parco dello Sport, a vast sporting complex built on 23 hectares of the former Italsider site. The 37-million-euro project, which was funded by the Campania region with help from the EU, featured fields, courts, and rinks for volleyball, basketball, soccer, tennis, and ice hockey and was surrounded by cycling lanes and canals for model boats. It was to be the crown jewel of a rehabilitated Bagnoli, attracting athletes from all corners of Naples. In 2010, funding was suspended, and, in 2013, it was discovered that the company that had built the complex, Bagnoli Futura, had not only failed to clean up the pollution in the soil below, but had used that same soil as a dumping ground for blighted earth from another nearby reclamation project.

Photo by Falcone Geddes

Walking around the Parco dello Sport, which closed before it ever opened, is an apocalyptic experience; an eerie and imposing place whose fields should be bustling with athletes, but which exists in a state of decay: tennis courts with the fencing torn down and overgrown children’s playgrounds, sacked for any materials that could fetch a price, littered with trash, and strewn with graffiti.

Romano explains that citizens of Bagnoli were initially relieved when the Italsider factory shut down in the 90s–“we went from not being able to open the windows when there was a spill to finally being able to breathe”–but that these sentiments quickly transitioned into disillusionment. “This factory has been here for 30 years and no one can understand why,” Romano elaborates. “Why have the various attempts stalled? Why have they often ended in corruption trials? Why did the money that was supposed to go to the cleanup of the area disappear into thin air?”

The abandoned Parco dello Sport; Photo by Falcone Geddes

The grunge and grit of the post-industrial area, however, is forgotten at the Pontile Nord, one of the few parts of Bagnoli that has been redeveloped and put to good use. Once the dock where ships would unload raw ore and reload pure steel is now a promenade that extends one kilometer out onto the sea. From the end, with a view of the entire neighborhood of Bagnoli, the white houses dotting Posillipo, and the abandoned, quiet shell of the steel mill, you can almost touch the lush island-turned-juvenile-detention-center of Nisida.

The contrasts are proof that something has gone truly wrong in this place, which had the potential to become a paradise.

Photo by Dimitri D’Ippolito

It makes one wonder what would have happened had the debate for the future of Naples in the late 19th century gone in a different direction. Following a series of cholera epidemics, the city’s drastic urban redevelopment, which led to Bagnoli becoming the industrial center of the city, was but one idea. Another, put forward by British-Neapolitan architect Lamont Young, would have transformed the entire western wing of the city–starting from Santa Lucia, through Posillipo and Fuorigrotta–into a series of canals and gardens, joined together by a system of trains terminating in Bagnoli, reimagined as a Victorian-style seaside resort complete with bathing piers and hotels. Ultimately rejected, the project, called Rione Venezia, didn’t account for the requirements of 20th-century manufacturing, though it would have given Neapolitans a proper stretch of usable beachfront, plus all the economic benefits that would’ve come with–a plan much closer to what many activists today call for the area post-industry.

Photo by Dimitri D’Ippolito

The seat of Bagnoli’s activism is Villa Medusa, a former private residence which was at first abandoned, then occupied and restored by community organizers. On the seafront, this Casa del Popolo is a library, gym, dancing school for seniors, and, above all, a gathering spot for the activism bubbling to the surface in Bagnoli, clamoring for the so-far empty promises of rehabilitation to turn into reality. “As a working-class neighborhood, Bagnoli was also a left-wing neighborhood, and it experienced moments of great labor solidarity. This is still present in Bagnoli; it’s one of the few remaining left-wing neighborhoods [in Naples],” Romano tells me.

Vaccaro was introduced to this space, and Bagnoli in general, during an apprenticeship at the City of Science in 2016. At Villa Medusa, he met Romano and Salvatore Cosentino, and the idea to make the docufilm about Bagnoli, to star locals and be produced by Vaccaro’s company Nisida Environment, was born. Romano and Cosentino were named director and co-director respectively of Flegrea – Un Futuro per Bagnoli.

Photo by Dimitri D’Ippolito

“We wanted to show […] how this looming presence, this non-place to which you don’t have access, influences your life choices,” Vaccaro continues. The choice between staying and leaving is a central theme of the film, as it is for many young people from areas that have been defaced and sullied. “It makes me angry that I have to leave and find happiness when I have it just a step away from home–but look at that crap,” Ciro, the male protagonist, echoes.

It was an illumination when Ciro and his sister Federica came in for casting; siblings born and raised in Bagnoli, full of dreams yet held back by the lack of opportunities in their land. Their grandfather had been an employee of Italsider before it was shut down. It was decided to center the film around their relationship and their growing realization about the ruination of their hometown.

Photo by Dimitri D’Ippolito

“The subject matter is scientific, environmental, then it becomes social and political. We aim to bring it down one step further to the human level,” Dimitri D’Ippolito, the on-set photographer for the film, says. “Bagnoli was killed. You can’t swim in the sea or eat the fish; the coastline has been denatured. But we couldn’t just focus on the ugly bits, we had to show the beauty of the sea, even if it is fucked.”

It’s partially because of this beauty that not all hope has been lost. When asked if she believes in a future for her neighborhood, Federica responds, “Yes, I do. Actually… I’m sure.” She dreams of “a big park, a playground where [she] can take [her] children, maybe with a nice Ferris wheel, and possibly a few more houses.”

“We have to work on the territory to create a place where, even if someone decides to leave, they have the possibility to come back,” Vaccaro asserts. D’Ippolito adds, “We wanted to tell this story for everyone in the world who is torn between leaving to find better opportunities or staying in the disadvantaged place which they love, with this love sometimes turning into hate. It’s not just about Bagnoli; the world is full of abandoned post-industrial areas that have collapsed local economies.” (To name but a few in Italy: Alessandria, which housed the largest Eternit asbestos cement factory for 80 years; the Sicilian city of Gela, where three million euros have disappeared in “reclamation” projects; and the Caffaro di Torviscosa area, in Friuli, whose groundwater and land is still gravely polluted with heavy metals.)

Perhaps another drop of hope can be found in a new reclamation project initiated in November of 2023 by Invitalia, with funding from the state, which aims to regenerate the land and restore the facilities of the Parco dello Sport; the aim is for the complex to (finally) open in 2025. As with all things in Bagnoli, under the shadow of the blast furnace, we must wait and see.

Photo by Dimitri D’Ippolito