Lately, I’ve got about 16+ tabs open in my browser at all times. There are a few duplicates–dedicated to the same family tree page on Ancestry.com, a scan of my great-grandfather’s naturalization document, Google Translate, a Facebook group dedicated to Italian Americans pursuing Citizenship, a half-drafted email to the small commune where my great-grandparents lived requesting birth and marriage certificates, flight searches to Rome, The 1950 US Federal Census and multiple YouTube videos listing out “The best things about living in Italy.”

This array of tabs tells a contradicting story. It is one of arriving and leaving. In an effort to make a permanent move to Italy from the U.S., I am applying for my Italian citizenship through my lineage, or “de jure Sanguinis”. Doing so requires a deep dive into my heritage and ancestry. Early on, this quest became just as much about where my family came from as it is about where I’m going.

I am one of many Boston-born Italian Americans. Both of my parents’ families originated from the impoverished Southern Italy of the 20th century. My dad’s family is from Sicily, and my mom’s is from a small town that lies almost halfway between Rome and Naples. Their grandparents immigrated to the Greater Boston area in the early 1900s and quickly dissimilated from Italian culture in pursuit of acceptance. In the process of applying for Italian citizenship, I’ve found myself face-to-face with their journey. It is inspiring and poignant; it is impressive and impossible to fully grasp what it felt like to leave everything that is yours behind in pursuit of hope. I’ve spent the last few months collecting every legal document–every birth, marriage and death certificate–that exists between myself and my maternal great-grandfather Arcangelo Valerio. The next step is getting them translated and apostilled, before dancing with consulate schedules. It’s a ruthlessly long, tedious and expensive process, which I can do nothing but accept.

Arcangelo, or Angelo as he became, was born December 1st, 1892, in a small commune in Campania called Strangolagalli. At 14 years old, he made his first trip to America. At age 20, he returned to Italy and married my great-grandmother, Assunta. Soon after, the two set off for America and settled in a town called Revere, a tenement for Italian immigrants north of Boston. Angelo was a boiler maker and Assunta a housekeeper. They welcomed their first child in 1913, and would go on to have five more children, including my grandfather.

The years passed, and while my great-grandparents tried to fully immerse themselves in American culture, they were very much still Italians living in the US. Their children, however, were brought up with a healthy dose of both cultures, and their identities began to lean more American. Perhaps the greatest shift away from Italy occurred with the passing of my great-grandparents. They could preserve their culture only as long as they were living. Once they were gone, family gatherings became smaller and less frequent, relatives moved outside of the neighborhood, and their grapevines and tomato gardens were left untended.

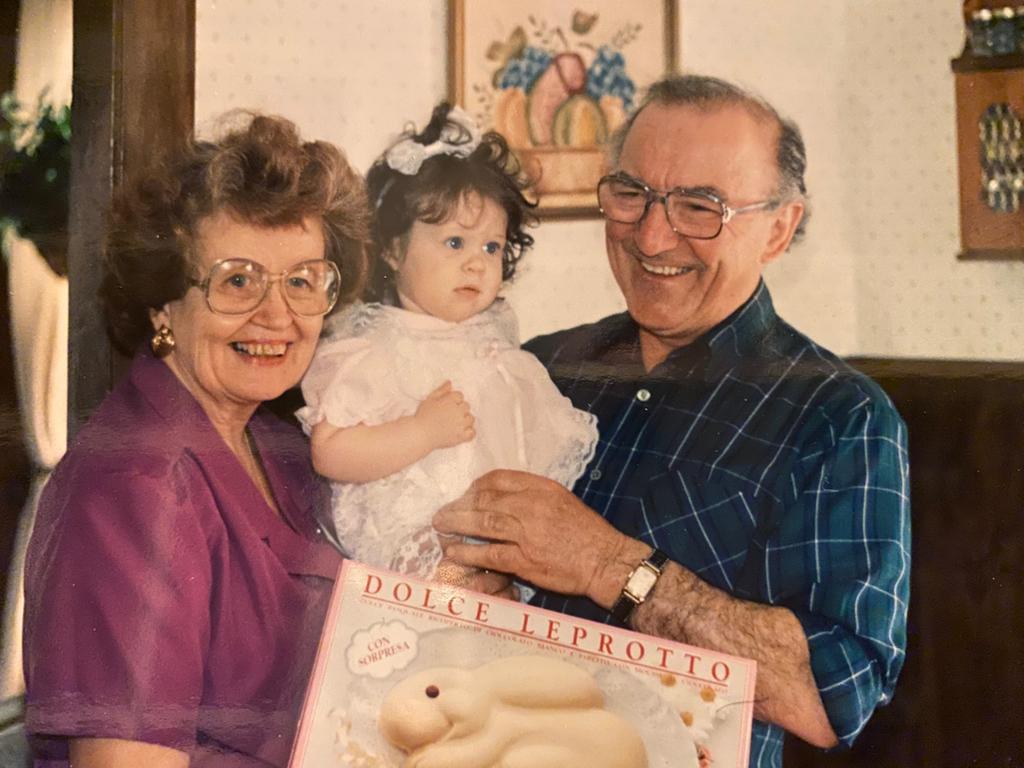

Author Gina and her grandparents

Having grown up in a small and modest town in one of the least diverse states in the U.S., the idea of moving to Italy and obtaining citizenship felt lofty at best–a dream only worth dreaming of. My family nurtured its Italian-ness to an extent, and though more American than Italian, some customs, traditions, and values were maintained. Sundays, without fail, meant my mom was in the kitchen, cooking a new batch of tomato sauce and my dad could be found (and heard) on the phone, talking to his mom, and then his sister, and then his other sister. Family get-togethers were plentiful and almost always included a spread of eggplant parmigiana, more meatballs than anyone should eat, and cannoli from Boston’s North End. Glasses housed my uncle’s homemade limoncello, and the word salute was seemingly on repeat. It was enough for a seed of curiosity to plant.

I’ve been told since I was young what my great-grandparents had to go through not just to arrive in America, but to be accepted by it. They were met with cemented beliefs that Southern Italians were inherently dangerous and brought with them criminal traditions.”Mafia” had become a household word, and Italian Americans found themselves with an albatross around their necks. It became apparent that to become American meant to become un-Italian. Their language wasn’t passed on, vowels were removed from their surnames, their children were given American-sounding names and they had to quickly renounce their Italian citizenship. In pursuit of joining the American mainstream, they turned away from that which they knew and towards a culture that was unfamiliar and unwelcoming.

About a century later, with the help of better infrastructure and a stronger economy, Italy had transformed from a place to escape into a place to escape to. From where I stood, Italy felt like a shared dream for all Americans. Between the food, the charm, the language and the sweet absence of America’s urgency and expectations, the peninsula was the full package. What better place to escape what burdens us and revel in the simple beauties of everyday life? So I leaned into the fantasy. There I was, one minute at work, seated at my desk, the next, eating paccheri, slowly and preciously, on a terrace at lunchtime with a glass of red from Piedmont. There I was, falling in love on the back of an Italian boy’s Vespa–Giovanni, Leonardo, maybe. There I was, tapping my foot and sipping a too-strong negroni at a jazz club in Naples. I’ve spent an embarrassing number of hours within these fantasies. I’ve willed them into a vehicle that’s driven me into a plan.

My plan to leave the U.S. for Italy and obtain my citizenship is in motion, catapulting me forwards and backward simultaneously. My move is a declaration, a promise and a vow to learn as much as I can about the people I share a bloodline with. I will appreciate the history, lives and realities of my ancestors. I will imagine them, celebrate them, tell and retell their stories. The other day, I shared with my dad my intention to relocate to Italy for the first time. His response was a sharp, “Your great-grandparents did everything they could to leave that place, and now you’re going to go back?” My answer is a clear and resounding “Yes.”