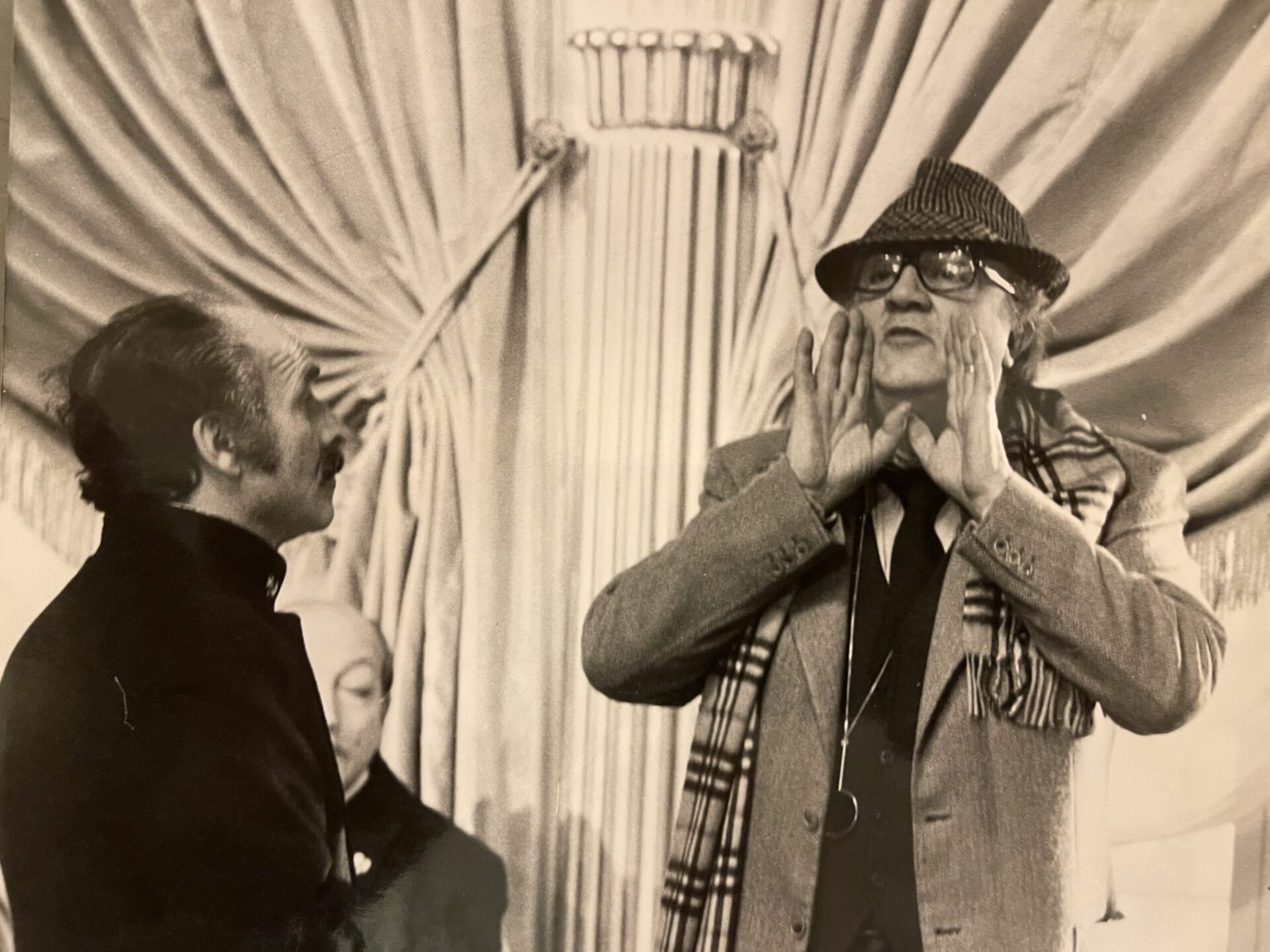

“One of the times when Fellini would take off his mask and was simply Federico was Christmas. Every year we spent Christmas Eve together at my house. […] Giulietta used to cook, helped by my wife, but I must say, in the kitchen he wasn’t exactly the best; instead Federico used to set the table. Master of direction that he was, he chose the seat arrangements and dressed the table as he pleased. I let him be without intervening.” So wrote Claudio Ciocca, host and owner of the restaurant Osteria del Fico Vecchio and the great director’s confidant. Close like brothers, the two were known for the hilarity that would ensue when they were together.

Fellini used to visit his friend in Grottaferrata practically every day when he was at Cinecittà shooting a movie or when he wanted to eat his beloved runny eggs: lightly-cooked scrambled eggs with a creamy consistency. Fellini was a gourmand; he loved food, but above all, he loved the conviviality born at the table.

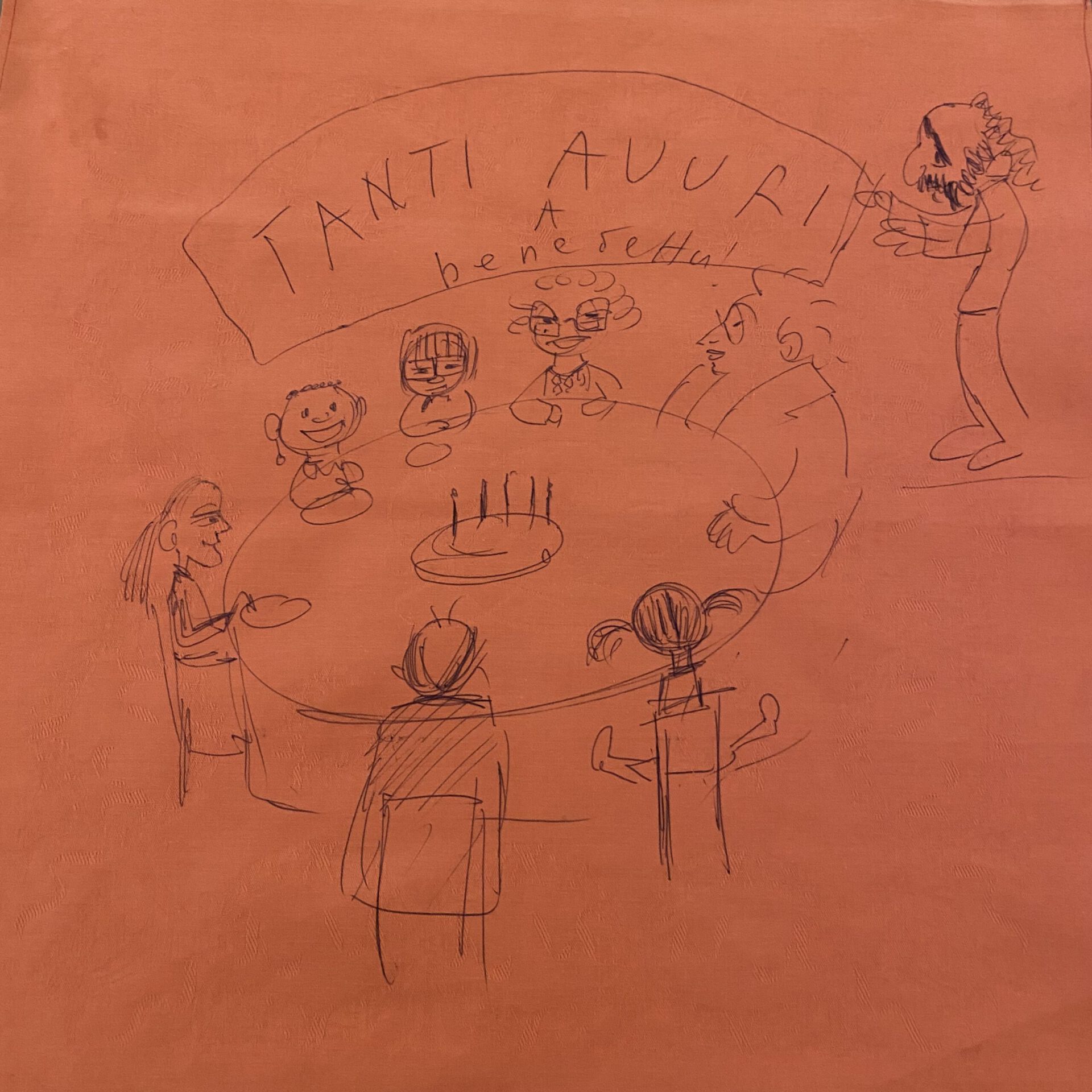

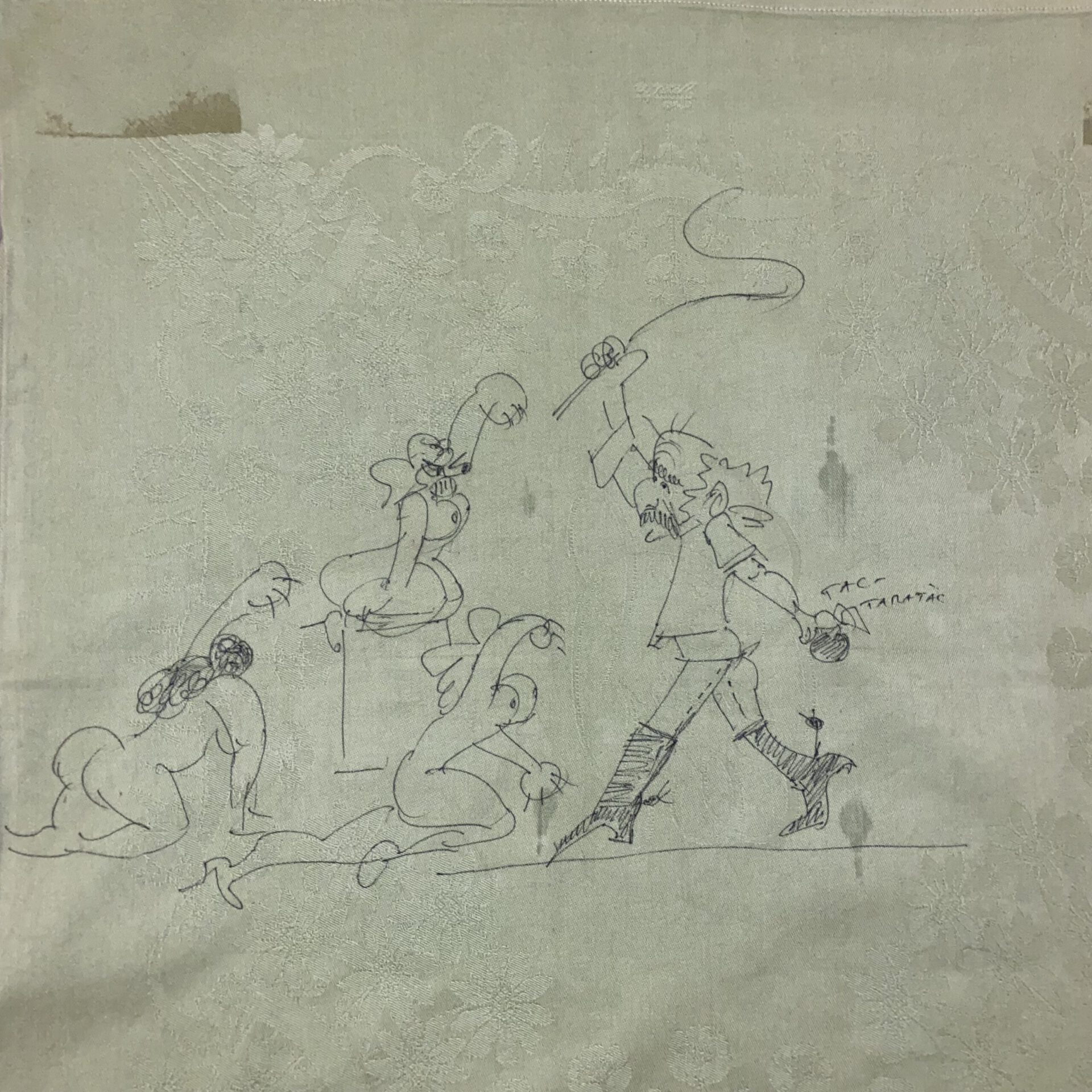

Anyone who had the privilege of sharing a meal with him could certainly confirm his unique and bizarre habit of drawing whatever came to his mind on tablecloths and placemats. He would take a napkin and jot down sketches of the people around him, creating caricatures complete with comic strips. His drawings conveyed a pure and childish freedom of expression, almost as if born at the hands of an adolescent. They were amusing, simple, and authentic. It is no coincidence that Fellini’s first job was as a caricaturist.

Photos courtesy of Osteria del Fico Vecchio

Drawing on tablecloths was his way of finding inspiration, and led to the birth of many of his films’ scenes. Claudio Ciocca would often get upset with him (although never seriously), since linens cost 2,000 lire, a very high figure for the time. At one point, the restaurateur started to bring stacks of white paper every time the director sat down at the table, so he could draw on those instead.

One of the director’s many culinary peculiarities was to ask for a piece of Parmigiano as soon as he sat down in a restaurant. His father, Urbano, was a liquor and food representative, and Federico used to say he was born with the scent of Parmigiano under his nose and couldn’t do without it. He loved hanging out in his neighborhood wine bars, engaging in long conversations about wine, cooking, and roasts, a dish he liked very much. Anna Dente from Osteria San Cesario once said that she was struck by Fellini’s unpretentiousness and his impartial devotion to Roman cuisine.

At the age of 19, Fellini tried to find his way by offering drawings and caricatures in restaurants. He worked odd jobs and didn’t always have the money to buy food. One day, he entered Ristorante Cesarina (on Via Piemonte in Rome) and ate everything and more, but when the bill came, he confessed he couldn’t pay and was thrown out of the place. Some time later, the owner found him in the neighborhood, cold and very thin, and invited him back. For an entire season, she fed him full meals, never asking for anything. Perhaps it is thanks to this very gesture that Federico Fellini became a frequent visitor of restaurants–perhaps he saw them as safe places to take refuge.

Fellini eventually did find his way and became the great director we all know. When it was time to organize the press conference for the release of La Dolce Vita (1960), he asked that it be held inside Ristorante Cesarina. Completely unknown to most, the establishment was a place he held close to his heart. Needless to say, after that event, the restaurant enjoyed worldwide success.

He frequented many restaurants–places to both relax and find creativity–and some he visited so often that it became almost normal having him there; he even had the keys to the Ciocca family’s house, and would occasionally show up without warning. Every morning he called Claudio on his home phone. The two men would tell each other what they dreamt of the previous night. These were the types of connections that Fellini established with restaurant owners and hosts. For him, they were not just places to eat, but rather worlds where he could be himself and nurture his closest relationships.

When he wanted to enjoy quality meat, Federico used to go to Dal Toscano al Girarrosto, on via Germanico. Here he drew a sketch of Paola, the restaurant owner, whom he nicknamed “Blessed Paola of the Meatballs”, since she made her meatballs in a particular flat shape just as he liked (they’re also named after him on the menu). Fellini was very picky and demanding with food, often giving directives on how to prepare a dish. He enjoyed giving his grandmother’s recipes or the ones that made him feel at home, seeking the flavors and memories of his childhood.

He also loved staging amusing situations around the table without others knowing. Sometimes, when he would go to Al Fico Vecchio for breakfast with journalists or friends, he wouldn’t order, but would manage to make his guests pick exactly what he wanted. He masterfully described a different dish to each person, explaining the taste so well that it made his companions’ mouths water, influencing them to order said dishes. He made it look as if he hadn’t ordered anything, but in the end, he sampled everyone’s dish.

Federico Fellini was a great lover of life, passionate about earthly things and the levity of laughter. He certainly liked to eat well, but there was unequivocally something stronger that made him love being at the table. It was about the people, relationships, and emotions. It was about real life.

When he walked into his favorite restaurants, it was as if he stripped off his notoriety and went back to being a regular person, simply a man. He didn’t have to think about what others expected from him; he could abandon himself to the serenity of a moment among friends. Everything was lighthearted, and for a while, the life of sets, interviews, and spotlights did not concern him.

It was in those moments of conviviality that Fellini was able to see beyond, to feel that there was something more. “I think the only true realist is the visionary,” he often said. And when he drew on the tablecloths what his mind imagined, he did nothing else but show others a great truth: the authentic beauty of that moment.