If this story was to be summed up in five words, they would be: saint, pants, gnocchi, lottery, and salary. Intrigued? Confused? Both? As was I when doing research on this particular (and at moments, peculiar) Argentinian tradition of eating gnocchi on the 29th of each month. For this story to be told, however, we have to go back in time…

…to the Medieval Era and a man named Pantaleon. Later on, he would become St. Pantaleon, or St. Pantaleo, patron saint of trousers–yes, like the pants–and the lottery, among a handful of other wide-reaching needs of believers. His story is long and complex, a true tale for the times. Born in Nicomedia (in what would now be Izmit, Turkey) of a religiously stoic Catholic mother and a wealthy pagan father, Pantaleon was pulled between these realms. After his mother passed, he veered away from the church and studied medicine, becoming a physician of the Emperor Galerius for a time. He was later swayed to return to the life of the church, performing a few miraculous healings and even converting his father before his death. Left with his father’s fortune, he gave it all away, freed his father’s slaves, and moved to Italy (what a vibe, Pantaleon!), a choice that gave him great adoration but also great enemies. Denounced to the Emperor Diocletian by his peers, the Emperor showed sympathy and gave him a chance to redeem himself–an opportunity which Pantaleon took to preach back to him and even heal a member of his court. Talk about a clap-back… This act of “magic” earned him a quick trip down torture lane. Think: use of wild beasts, molten lead, torches, and attached weights, thrown in water, swords swung, and ropes tied, among other wickedly creative pursuits, yet nothing could kill Pantaleon. He eventually came to his demise by the sword, but not before asking for forgiveness for his torturers and giving permission to his executioner, embodying the Greek meaning of his name until the end–“mercy for everyone.”

And so, our first chapter of this saga of a story is complete. You now know of Pantaleon (phew). So, again, why do Argentinians eat gnocchi on the 29th of each month? We’re getting there…

We don’t really hear much about Pantaleon until the Elizabethan era. Having become a popular saint in financially-booming Venice, his name and connection to wealth becomes a comical trope in Italian commedia dell’arte, particularly in the Venetian theater scene. Both Shakespeare and Goldoni refer to a Pantaleon character in their works, usually represented by a wealthy but silly, learned older man who sports trousers rather than knee breeches, also known as pants, a Venetian style that would come to permeate fashion for centuries.

Saint Pantaleon

While the theater tale is only vaguely agreed upon, the Italian familiarity and cultivated connection in popular culture between wealth, luck, success, and this Saint Pantaleon-influenced character grows and is strengthened at this time, becoming a theater classic and household saint name equally–so much so that it follows the Italian diaspora to various new homes, new homes like Argentina, where there is hope for a fruitful future.

Finally, you must be thinking. Yes, for all the long-windedness, we are nearly there…

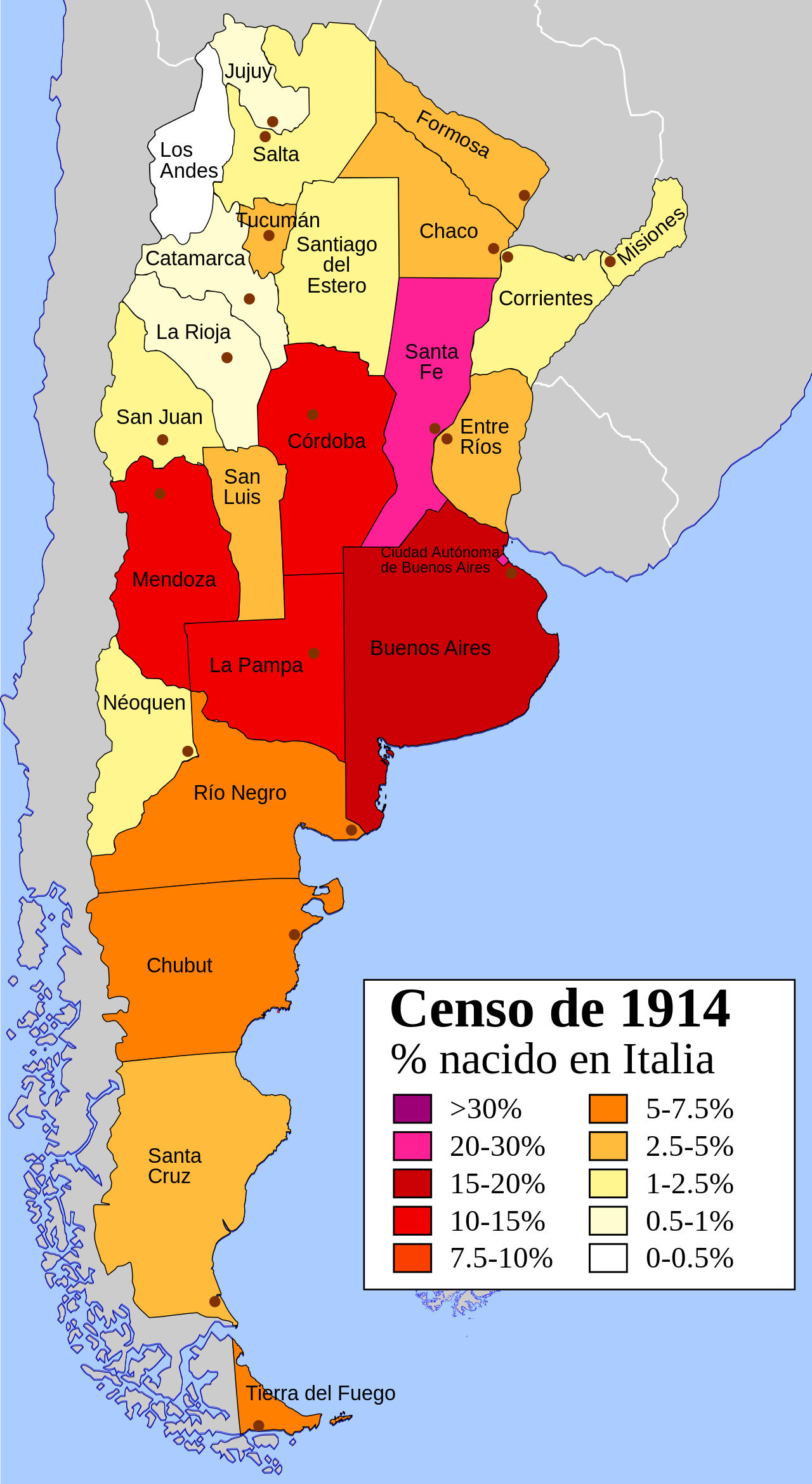

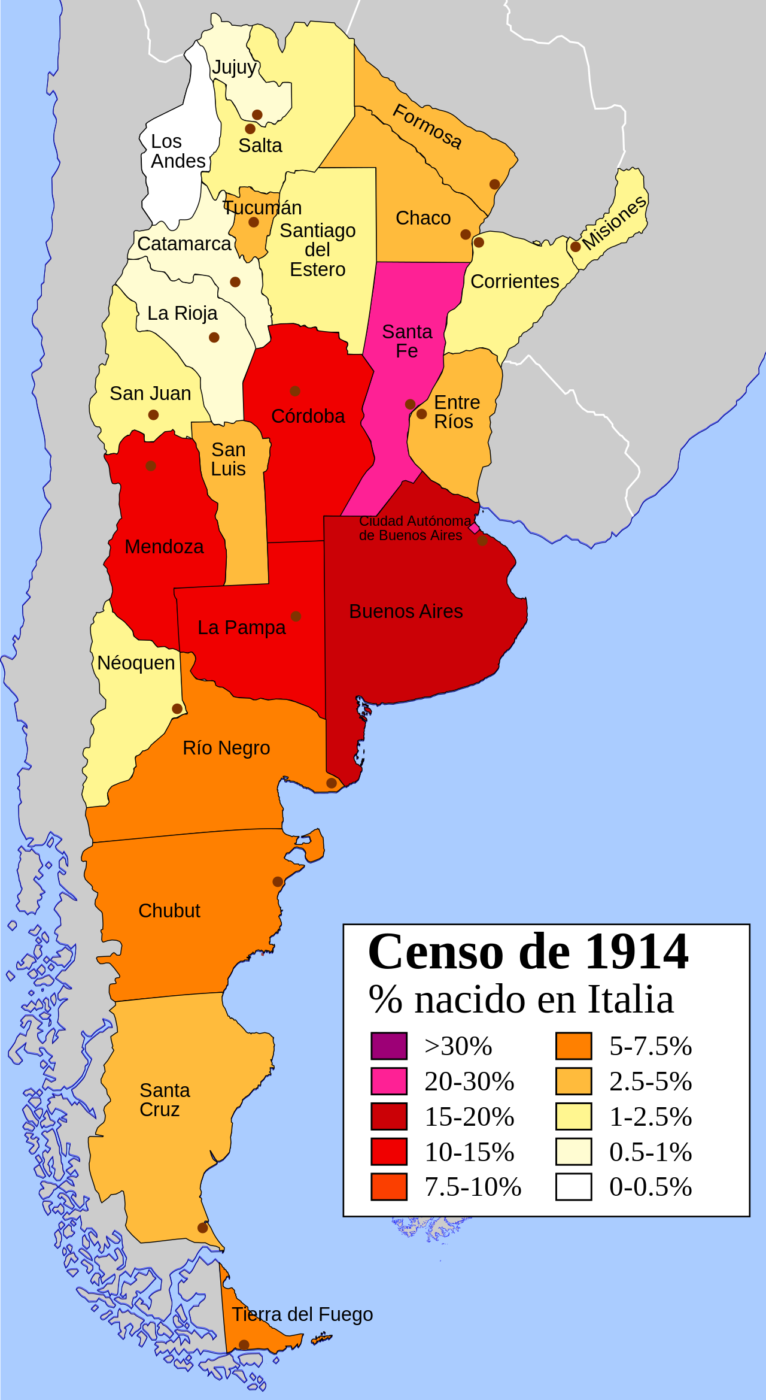

Between the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, Argentina accepted millions of immigrants from Italy. A variety of contributing factors fueled this emigration: the wants of the Italian government in sending away its poor while simultaneously “culturally colonizing” South America was met with open arms by the Argentinain government, who desperately needed to repopulate the empty plains once worked by its own people, people who were killed off by the “Conquest of the Desert,” a government-sponsored genocide of the 1870s. Italian migrants moved into the Pampas region of Argentina, where the Mapuche lived prior to the genocide. Their staple crop? The potato. With ready access to starch (and not just the potato–yuca, or manioc, was also in ready supply), it was a no-brainer to make dumpling-like pasta; here, however, it is not gnocchi di patate but rather ñoquis de papa. (A silly aside: this term has also now come to reference people with high-paying positions who don’t actually do much.)

So, consider yourself in this position: a newly arrived Italian migrant, living and working in Argentina at the turn of the century. Perhaps a laborer, perhaps a farmer–either way, not yet established and wealthy enough to be living comfortably enough. As an ama de casa (housewife) with a spouse’s paycheck coming at the end of the month, you make do with what you have left in the pantry, and like many Italians, you think of the dependable filler-upper, the satisfier of stomachs, the hero of hunger: a pasta dish. You set your table, gather your family, and prepare to eat–but not before a prayer. You pray for luck, for wealth, for health, for victory; you pray to Saint Pantaleon, who was lucky in his life, came from wealth but gave it all away, provided health to those he touched, and who was victorious in his death. You may even slip a bill or an old paycheck under your plate as a symbolic offering or token of fortune on this auspicious day, for the 29th is not just the last days of frugality before payday, but it is also St. Pantaleon’s day.

Amid all of this history and somewhat antiquated beliefs, Saint Pantaleon continues to permeate the more interesting corners of Catholicism. His realm of influence covers physicians, midwives, and livestock; is believed to cure headaches, loneliness, and consumption; and protects against wild locust attacks, witchcraft, and accidents. And that’s not to forget that he’s the patron saint of pants–after all, you may just need him when you forget that winning lottery ticket in the pocket of your trousers.

Today, you won’t see much of this tradition outside of the Argentinian home or small, family-run restaurants. As with many religiously-affiliated and artisanal practices, having ñoquis on the 29th remains with the abuelos–a not unfamiliar happening in Italy, either. However, resurgences have occurred. A Google search revealed some recent evidence: a Houston restaurant offering all-you-can-eat gnocchi on this monthly day (minus February, of course), a bistro in Boca Raton captioning their saucy shot of a plate of gnocchi with “Hoy 29 día de los ñoquis!” (“Today is the 29th, it’s gnocchi day!”), an Argentinian Instagram cook making a gluten-free version to celebrate. It’s not a dead tradition, but perhaps one that has been absorbed into the overall popularity of trends like pasta-making, gnocchi base alternatives, and air-frying madness.

It would be poor manners to leave you hungry after telling this tale, so here’s a ñoquis recipe to whip out on the next 29th. Just don’t forget to pay your respects to you know who!

Ñoquis de Papa

Serves 4-6

INGREDIENTS

- 500 g potatoes or yuca

- 130 g flour

- 0.5 teaspoon salt

- 1 egg (room temperature)

- ~13g (1 spoon) of oil (corn, sunflower, olive)

- 1/2 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg (optional, best when serving with butter- or cream-based sauces)

PREPARATION

- Put the mashed potato/yuca in a bowl and add one egg yolk. Add oil and a pinch of salt and nutmeg, if using, and mix by hand.

- Add the flour. Knead the mixture in the bowl for about five minutes and add a little more flour, as needed, until the mixture has a soft, dough-like texture—not too sticky and not too hard or dry. It should have the same texture as the dough for white bread.

- Divide the mixture into four and sprinkle some flour on top. Then roll out the first quarter of the mixture onto a floured work area, making a long, thin roll about one inch wide.

- Cut the roll into one-inch-long pieces. Take each piece and press your thumb slightly into it, rolling it gently down on a wooden gnocchi tool or using the back of a fork.

- To cook the gnocchi, boil a pot of water, add some salt and a drop of oil. Drop the gnocchi pieces in, and when they rise to the top (after about 1 minute), scoop them out with a slotted spoon.

- Serve with your favorite sauce—gnocchi goes well with everything!