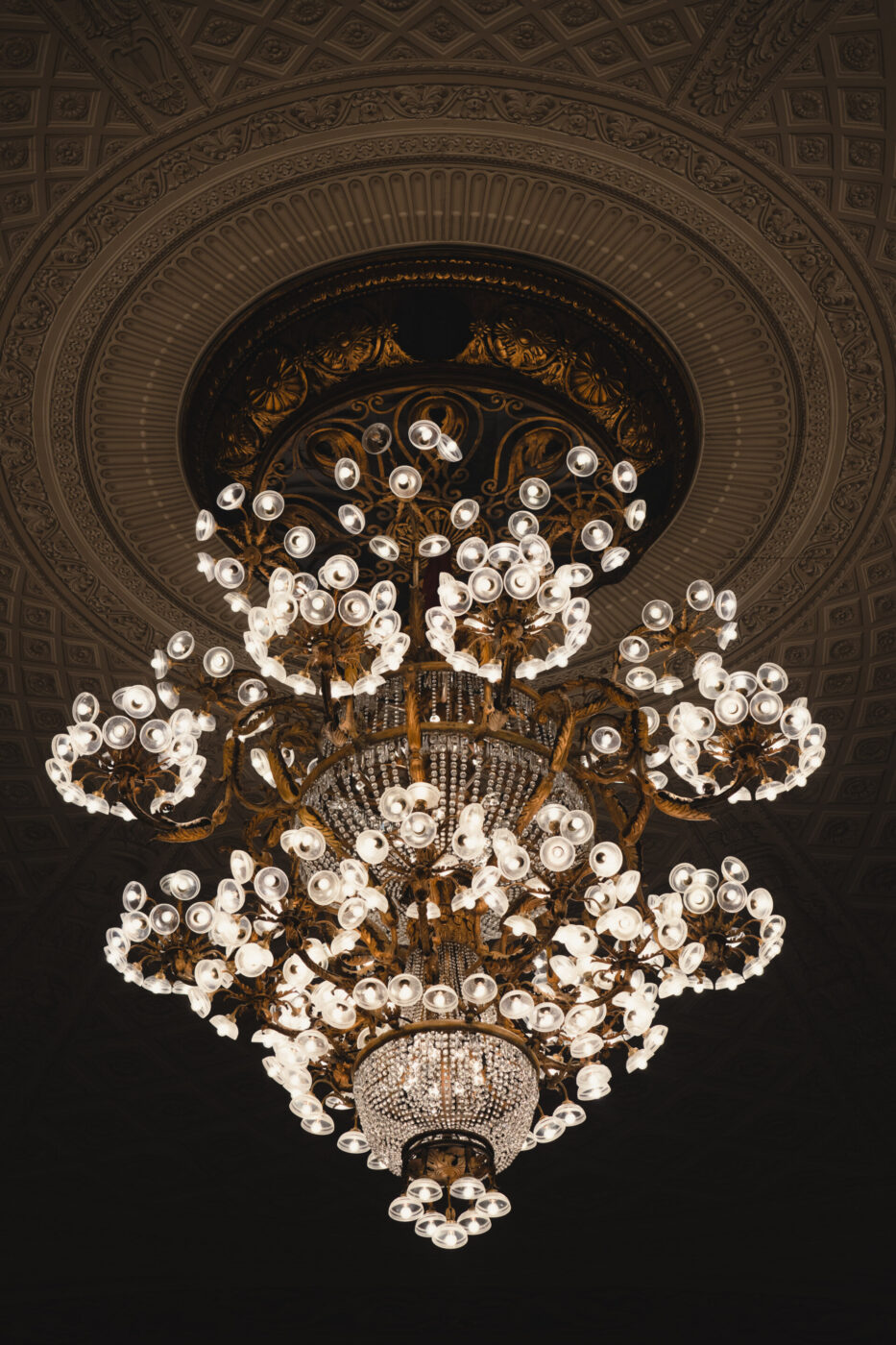

The theater boxes of La Scala certainly are plush

They didn’t just appear there on stage overnight, you know. The gilded interiors of Don Carlo’s Baroque palace, Juliet’s Veronese balcony, the midnight blue velvet gown Maria Callas wore in her role as Anne Boleyn in 1957. Every set, sculpture, and immaculately crafted costume that captivates audiences on stage at Milan’s beloved Teatro alla Scala is an artistic feat in and of itself–odes to both creative innovation and centuries-old Italian handmade traditions. Right at this moment, scenography feats, dream worlds, and impossible realities are being brought to life inside an unassuming industrial warehouse on Via Bergognone just outside Milan’s city center.

Benvenuti a Ansaldo; La Scala’s artistic laboratory where set design and construction, sculpture, carpentry, mechanics, and costumes for every production come to life by the hands of expert artisans from all over Italy–the other stars of La Scala. Inside this 20,000 square-meter workshop of wonders, historical artisanal skills are preserved and continued, visionary creative minds collaborate and dream up the grandest theatrical sets, and meticulous hands craft the kind of masterpiece costumes that would make any alta moda devotee weep at the mere sight.

Inside Ansaldo

A former industrial site where trains were assembled, La Scala moved its set design and artistic operations into Ansaldo in the early 90s and was officially granted the warehouse as its laboratory by the Municipality of Milan 2001. Grande? A grand understatement! Divided into three main areas dedicated to set design and painting, sculpture, and set construction, Ansaldo reduces human to ant proportions. Naturally, the sets created for what is considered by many to be the world’s grandest and most storied opera house are impressive in scale. But one perhaps doesn’t realize just how impossibly vast and detailed they are when watching a spectacular in the theater from Row H, M, P, or if you’re lucky, perched up in one of La Scala’s velvet-padded balcony boxes. That’s until you step inside Ansaldo.

Tailor Sonia Pavanetto

Whether it’s a reimagined vision for Cesti’s Baroque opera Oroneta, set in a contemporary art gallery, or thousands of hand-painted clouds for a panoramic sky in the ballet Giselle, no set is too enormous, no scheme is too elaborate, no design is too ambitious for the artisans at Ansaldo.

“The special thing about La Scala is that the majority of what audiences see on stage is created here ‘in-house’ at Ansaldo,” says Head Scenographer Emanuela Finardi, who has been overseeing the creation of these epic theatrical feats from one season to the next for 35 years at La Scala. “This is quite unique these days. There are not many opera theaters in the world that achieve the entire set design and construction process internally under one roof.” Finardi is a powerhouse; constantly running around Ansaldo from one set to the next, from one department to the other, ensuring that no detail is left unturned and that every artisan has the creative direction and resources required to bring their theatrical labors of love to life.

“It’s such a rewarding experience working here and seeing artisans from every department collaborate to bring a set to life. It’s like a harmony when everything comes together for the final result,” she says.

These streetscapes are meticulously hand-painted

Watch your step! You wouldn’t want to be the one who accidentally treds on part of the hand-painted streetscape that will take pride of place in Nino Rota’s opera Il cappello di paglia di Firenze. Despite its 20,000 square-meter floor plan, space is still a premium inside Ansaldo. In the first and largest of the warehouse’s three sections dedicated to set design and decoration, it’s not uncommon for artisans to be working on sets for up to six productions at the same time. With utmost caution, you tip-toe past giant boards, podiums, and pillars. Past workbenches covered with paints, brushes, sketches, and mini modellini of set designs stamped with the words: “NON TOCCARE!” (“DON’T TOUCH!”)

“We have 24 artisans who work in the scenography department, seven who work in sculpture, and 40 in construction. Within their teams, they collaborate to overcome all sorts of artistic and creative challenges. Sometimes they have to do the ‘impossible’–like creating sets with impossible perspectives and proportions, while still creating environments that the performers can move around in,” Finardi tells us.

This skull is made of styrofoam!

And as for those giant trees, statues, and monuments that create a seemingly eternal sense of place and context on stage in any given production… Can you keep a secret? Styrofoam! Ansaldo’s sculpture department is a revelation. Artisans mold and finesse masses of the material into desired shapes and forms, sending snowy sprays of tiny foam balls into the air. “Everything has the illusion of looking very heavy on stage, like stone or slate or bone perhaps, but it’s really all leggerissima [very light]!” says Finardi, who picks up a sculpture of a giant horse’s skull with one finger and holds it up above her head. “Voila!”

The same goes for the set construction department, where they use all sorts of tricks of the trade to build scenic elements like walls, staircases, and supports that are sturdy but deceivingly light. It’s not a matter of building a table according to typical furniture-making conventions and materials. It’s a whole new construction language here.

“Sometimes the artisans must revisit old techniques to replicate construction processes as accurately as possible, especially when creating set elements for historical productions. But generally, it’s a balance of tradition and innovation. Of course, we use new materials and technologies like 3D printers, but we always go back to the Italian tradition of the handmade, as it has always been done here at La Scala,” says Finardi.

Styrofoam sculptures in the works

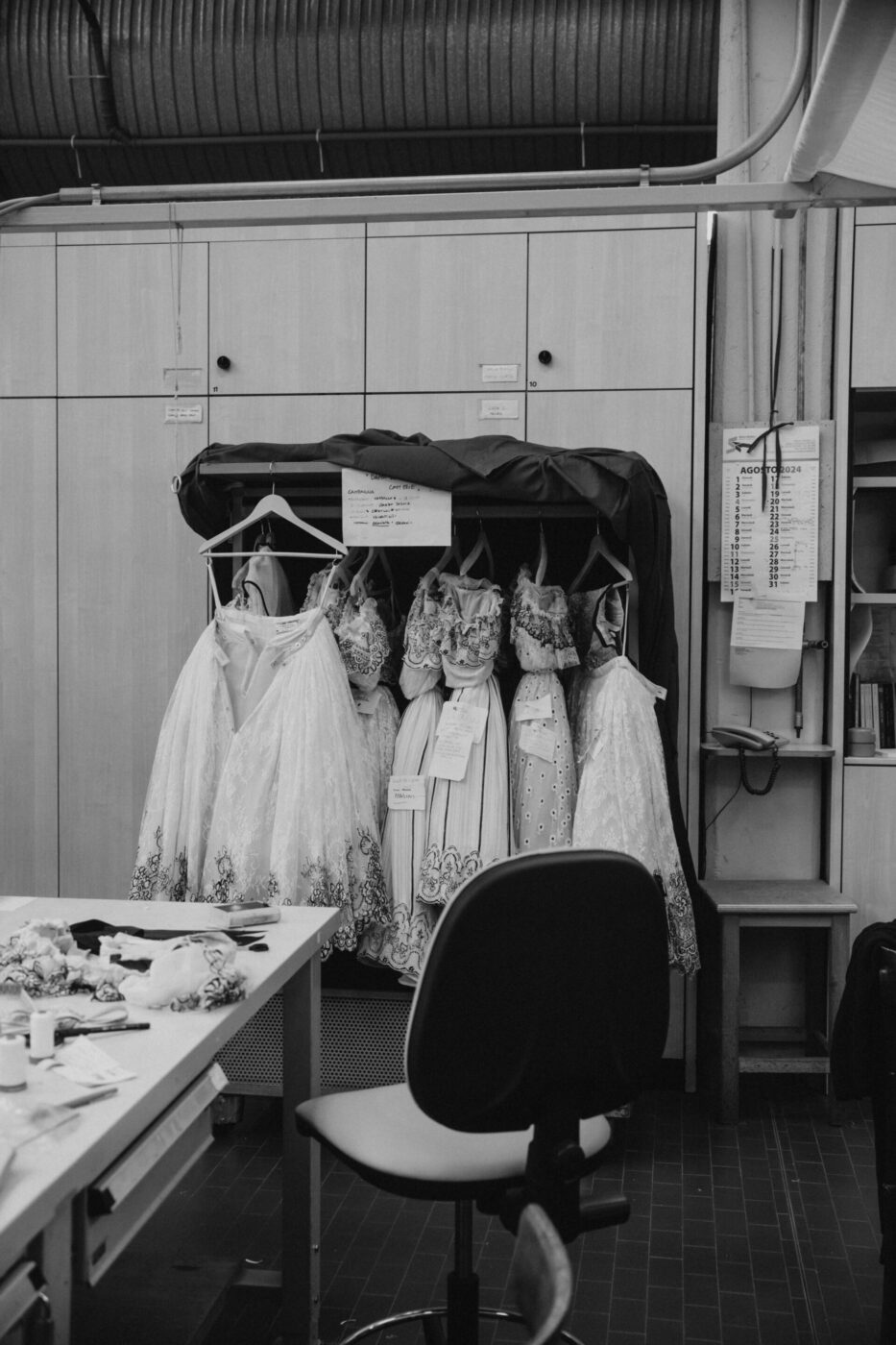

In another building adjoining the main warehouse, La Scala’s Sartoria is a labyrinth of sewing machines, cutting tables, fitting rooms, and shelves stacked with rolls of fabric in every color, tone, and texture. Eight hundred to 1,000 new costumes are created here every season, with specialist tailors, seamstresses, cutters, fitters, and drapers weaving their magic via historical tailoring techniques that have been observed for hundreds of years in the worlds of opera and theater. The tagliatori (tailors) who work in the Sartoria continue a rare profession that demands a supremely artful set of skills. In the case of any historical opera production set in the 17th or 18th century, for example, they must research paintings and images to understand the shapes and nuances of silhouettes from the period and proceed to create garments that are truly “of the time” while ensuring they will fit more diverse body shapes of today. This is one of several reasons why this sartoria is not to be mistaken for a fashion atelier.

“What our tailors do in creating these costumes might be perceived as similar to Alta Moda. It’s a similar kind of work, but not the same thing. Alta Moda garments can be worn in different situations, and ateliers consider the fact that the wearer can still do ‘everyday’ things like walk around and drink a coffee in them. They might be described as garments more tailored to the physiques and bodies of today. In contrast, the historical tailoring of theater costumes transposes ancient conventions for sizing and silhouettes to today’s bodies. This is a subtle but important difference,” says Finardi.

We breeze down a long corridor lined with racks of decadently embellished capes, corsets, and dresses from the ballet L’histoire de Manon. They are works of wearable art, each one crafted from layers upon layers of velvets, silks, tulles, and ribbons in a rich autumnal color palette, detailed with the most intricate golden hand-embroidery, beading, and trims. Finardi leads us around a corner and points out the Lavanderia, the room with special industrial washing and drying machines where these precious garments are cleaned and primed after every performance before transportation back to La Scala again. Some are so delicate they can’t even be cleaned with water. Beyond this is the Modisteria, the space where artisans meticulously hand-craft hats, wigs, and headwear according to historical theatrical techniques. From jeweled crowns for AIDA to a handsome line-up of early 19th century pompadour-style wigs for Don Pasquale, the artisans in this department are preserving another rare theatrical profession and set of skills with every museum-worthy masterpiece they create. Then Finardi asks with a smile: “Would you like to see the costume archive?”

The room where the magic happens, i.e. where the costumes are painted and decorated

If you think you have a problem squeezing all of your most precious gowns into the wardrobe of your Milanese apartment, imagine storing 60,000 La Scala costumes–and counting. La Scala’s Magazzino Costumi puts any couture house’s archive to shame, and it must be one of the city’s best-kept “secret” treasure troves. We’re talking gems created in the 1930s when the Sartoria was under the direction of legendary costume designer Luigi Sapelli, who reinvented theater costumes through a contemporary lens via the use of new fabrics and decorative techniques. We’re talking about costumes embellished with the most precious materials like pure gold thread and original cameo shells that are no longer used in the Sartoria anymore. There’s even garments by the likes of Giorgio Armani, who created a voluminous, flower-embellished opera gown for soprano Janis Martin in 1980. Not to mention the costumes worn by history’s most adored opera and ballet stars who’ve graced La Scala’s stage over the years: Rudolph Nureyev, Carla Fracci, and of course “La Divina” herself, Maria Callas. Every few months a selection of these masterpieces (such as Elisabetta’s gold-trimmed velvet gown worn by Maria Callas in the 1953/54 production of Don Carlo) are brought out and displayed in glass cabinets under strict lighting and temperature conditions for the public to view on appointment–a must-see, lesser-known treat for opera and culture buffs in the city of Milan.

Not your average mood board; Photography by Gareth Paget

Who would have thought such an artisanal “dream factory” could be whirling around inside the austere walls of an unsuspecting industrial warehouse just outside the center of Milan? It’s that building you’ve probably walked past on your way to the supermarket several times a week and never looked twice at. The mere mention of the name “Teatro alla Scala” brings a twinkle to the eye of most Milanesi, and most Italians for that matter; a global symbol of the country’s cultural and artistic excellence. But a twirl through Ansaldo reveals another side of La Scala–the theater behind the theater. In here, human hands transform the raw, the formless, and the “blank canvases” into visual masterpieces for the stage, enveloping us in worlds where life imitates art.