Federico: This lady coming home, skirting the wall of this ancient patrician palace, is a Roman actress, Anna Magnani, perhaps the symbol of the city.

Anna: Who am I?

Federico: Rome seen as she-wolf and vestal, aristocratic and ragged, gloomy and buffoonish… I could go on until tomorrow morning.

Anna: A Federì [“Federico” in Roman dialect], go to sleep.

Federico: Can I ask you a question?

Anna: No, I don’t trust you, bye. Good night!

So theatrically Anna Magnani goes down in history at the end of Federico Fellini’s Roma, the film that precedes Amarcord. It was 1973 and, in the 50 years that have passed since, there has been no actress who equaled the greatness of “Nannarella”, the tender diminutive we use for her. Federico had courted her to make that cameo and she’d been resistant–he called her that “wild girl who used to react with arrogance, impudence and distrust.” Anna Magnani always sought in her profession the love that she lacked in life, and that so-called distrust was a product of her troubled familial and romantic life. In the wonderful documentary La passione di Anna Magnani (2019) by Enrico Cerasuolo, we see an interview in which a journalist asks the actress about the greatest joys of her life. Her answer is chilling: she holds her breath, as if rewinding the tape of time in a deafening silence, to finally realize that there had been very few. But it was this suffering that granted her the miracle of a magnetic gaze and a virile strength, which pushed us to value, for the first time in Italian cinematic history, another kind of femininity. Anna Magnani revolutionized the way people saw women in cinema, of course because she was an incredible actress, but also because she broke the bombshell mold of the time, playing women who beautifully and proudly wore their scars and wrinkles–both metaphorically and physically.

In 1961, while receiving the Mimosa d’Oro–an award for women whose works contributed to female emancipation–she affirmed, “I’m glad that it has been noticed that I also act to help women feel better and be more free.” What immediately made Anna different from all the other actresses of the time was her conviction in giving a voice to “normal” women, with the everyday issues of common people. Anna was true: she was a real person we could relate to. But there are three roles, among many others, that are emblematic of the type of femininity she wanted to represent: Pina in Roma città aperta (1945), a lower-class woman resisting the Nazi occupation of Rome; Maddalena Cecconi in Bellissima (1951), a working-class mother who desperately tries to get her daughter a movie audition; and Mamma Roma in the eponymous movie (1962) as an ingenuous prostitute. If we take into consideration the scope of cinema at her time, it won’t be misleading to affirm that Anna Magnani fought against the ideas of Fascism, as much as political forces of Italian Resistance.

EARLY LIFE AND CAREER

Anna is born in March, 1908, near Porta Pia in Rome, and immediately takes the surname of her mother Marina Magnani. Starting with her father, she has a tormented relationship with the male gender: she will only discover her father’s name as an adult–Pietro Del Duce. As a staunch anti-fascist, she even makes fun of her “luck” for not being “the daughter of the Duce”. After Anna’s mother moves to Alexandria, entrusting Anna to the care of her grandmother Giovanna, Anna grows up with her aunts. Following a failed attempt to reconcile with her estranged mother in Egypt, Anna returns to her city with the firm conviction that she wants to become an actress.

She is just 19 when she begins attending the “Eleonora Duse School of Dramatic Art”, and it is in the “teatro di rivista” that, together with the De Rege brothers and Totò, she obtains early acclaim. Particularly popular between the 1930s and 1950s in Italy, the “teatro di rivista” (or simply “rivista”) was a theatrical genre that mixed music, dance and acting, without following a specific plot. At ease in such an eclectic genre that best suits her wide acting range, she is discovered in 1941 by Vittorio De Sica, who offers her her first brilliant role in Teresa Venerdì. In the seven years prior, Anna has already collected several appearances on the big screen, also starring in Cavalleria by Goffredo Alessandrini, the man she married in 1935. Notably, her husband filmed her from a distance as if her face was too “risky” to show in the foreground: Alessandrini believed in the fascist mentality of the moment and Anna’s femininity was far from being the charming stereotype of the Hollywood divas.

This relationship with a man who, just two years later, will win, together with the legendary Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, the Coppa Mussolini for the best film in Venice (the forerunner of today’s Golden Lion) does not last long. After Teresa Venerdì, Anna becomes an important name in the Italian “star system”, but refuses to stick to just comedy roles. Although she is cast in Luchino Visconti’s Ossessione, the opening film of Neorealism, Anna is pregnant (and has not been totally honest with the famed director about it). She bitterly gives up the film for Luca’s birth, her only child who, once again in the absence of a father, takes the mother’s surname.

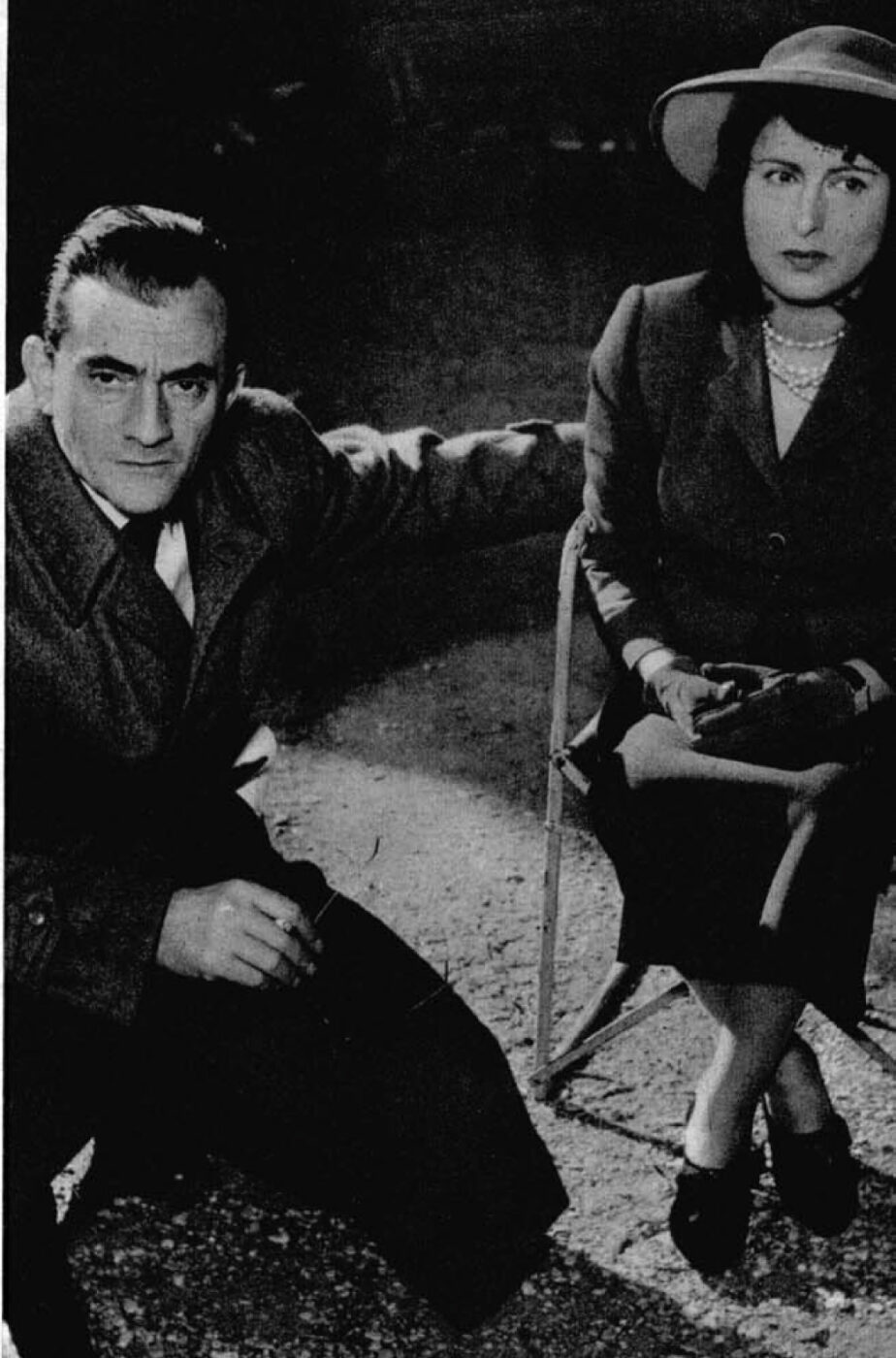

Luchino Visconti and Anna Magnani, 1952

ROBERTO ROSSELLINI AND “THE WAR OF THE VOLCANOES”

But Anna is not a woman who is intimidated easily: in two theatrical performances during the Nazi occupation of Rome, she daringly screams, “freedom!” And in 1945, the role of her lifetime finally arrives: directed by her new partner Roberto Rossellini, Anna is cast as Pina in Roma città aperta. Pina is a commoner, who fights against the Nazi occupation of her neighborhood and tries to protect her husband Francesco from German soldiers. The scene, set in Via Montecuccoli in Rome, in which she runs behind the Nazi truck that has captured Francesco, while screaming his name, is probably the most iconic scene of Italian Neorealism and one of the most celebrated in Italian cinema. Her embodiment of the Roman Resistance opens a gash in the history of Italy: her despair, while screaming “Francesco”, shakes the entire nation. Anna becomes the icon of a destroyed country, but also the symbol of its possible rebirth. Nobel laureate Giuseppe Ungaretti is not indifferent to the performance either and writes to her, “I heard you shout Francesco behind a truck, and I have never forgotten you”: neither will the Italians.

Anna is getting along wonderfully with Rossellini until he receives a letter from the Swedish actress of the moment. Ingrid Bergman is very impressed by the screenings of Paisà and Roma città aperta and sends him the following message: “If you need a Swedish actress who speaks English very well, who has not forgotten her German, who is not very understandable in French, and who in Italian knows only ‘Ti amo’, I’m ready to come and to make a film with you.” When Paisà is nominated for the award of best original screenplay at the Oscars, Roberto heads to America without Anna and meets Ingrid.

Ever since Panaria Film showed him some underwater clips shot on the island of Stromboli, Rossellini is thrilled at the idea of making a film in the Aeolian islands in Sicily. Without informing Anna–who is supposed to be the protagonist–Rossellini asks Federico Fellini and Sergio Amidei to write the subject of his following film: Bergman is to interpret the main character. Unable to resist the fascination of the Swedish beauty, the American billionaire producer Howard Hughes (the aviator played by di Caprio in Scorsese’s movie) is convinced to produce Stromboli – Terra di Dio.

Anna goes on a rampage and agrees with Panaria Film to shoot, on another island not far from her partner and her partner’s lover, Vulcano, directed by William Dieterle. This is how the so-called “war of the volcanoes” began. The events of the love triangle start to fill the pages of magazines around the world, so much so that even politicians weigh in and a Colorado senator calls Ingrid Bergman “a public concubine”. The excitement skyrockets: journalists and members of Vulcano’s troupe keep trying to reach, in disguise, the island of Stromboli to find out more about the shoot. Rossellini, whether due to severe psychological stress or a creative crisis, locks up the set. The filming of Vulcano goes much smoother, but nobody cares that much about the movie as, right during the première, the news is dropped: Ingrid Bergman has just given birth to Robertino Rossellini.

The war, however, will have no winner as both films will not have the hoped-for success. Only a bitterness emerges in Anna: “Why am I successful only as an actress while I destroy everything I have as a woman?” she asks.

Her last interpretation for Rossellini in the episode La voce umana (The Human Voice, recently remade by Pedro Almodóvar and Tilda Swinton) of the film L’amore (1948) is painfully prophetic. Magnani’s virtuosity in bringing to the screen the desperation of an abandoned woman at the end of her love is heartbreaking and moving. Among her words, a last painful promise snatched from her old man: “Promise me you will not go to the same hotel in Marseille where the two of us went.” Regardless, Rossellini will visit the Hotel Luna in Amalfi with Bergman, already the site of several stays with Magnani.

After the interlude of the volcanoes, Anna is once again ready to enchant audiences with new roles, including the unforgettable Maddalena Cecconi in Luchino Visconti’s Bellissima (1951). Various ideas and iconic lines in the film are the result of her spontaneous ingenuity: “I feel more like an artist than an actress: we all have thousands of women inside, not just one, and I am fulfilled when I am free to let them out. If I play as an actress, it is bad for me and for the film.”

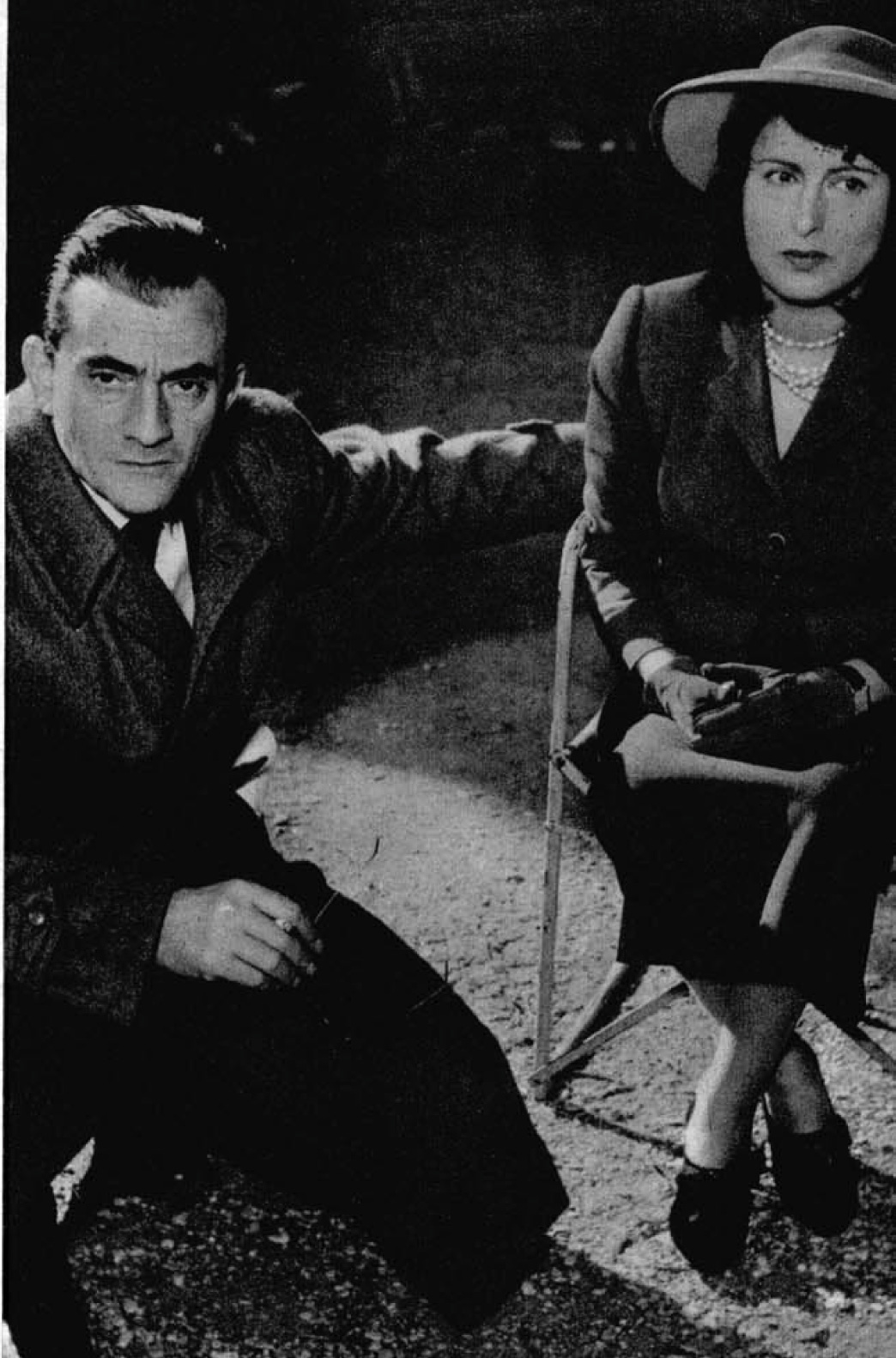

Anna Magnani, Goffredo Lombardo e Roberto Rossellini

THE OSCAR AND THE INTERNATIONAL SUCCESS

March 21st, 1956: Marlon Brando reads the Oscar nominations for best leading actress and Anna is the winner. In the history of the most coveted award in the world, she remains the first non-English-speaking actress to nab it. Her award-winning role in The Rose Tattoo is written for her by Tennessee Williams and inaugurates her American season, which continues with George Cukor’s Wild is the Wind, her second Oscar nomination, and Sidney Lumet’s The Fugitive Kind, curiously alongside Brando. It is known that there isn’t a particularly good relationship between the two actors–both with such peculiar, unmalleable personalities. However, Magnani admits that she is unable to judge that man whose fragility easily turns into violence.

After her American interlude, Anna is offered the movie La ciociara (Two Women, 1960). Author Alberto Moravia has sent Anna a copy of his book, but the actress refuses the part once she learns that she would play the mother of the emerging Sophia Loren. Loren’s Oscar for that role will send a clear signal to cinema italiano: the world is changing its perception of Italian beauty. Anna goes her own way and becomes Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Mamma Roma. It is, again, an extremely troubled filming that causes quite a few disagreements between the two intellectuals: regardless, they leave with mutual respect, and the movie is still considered one of the great masterpieces of Italian cinema.

LAST WORKS

Close to the unexpected end of her career, Anna goes back to the theater for one last appearance in Medea (Rome, Teatro Quirino, 1966). Playwright Eduardo De Filippo tells her: “The strength, the beauty of voice and the spontaneity of gestures… I only come [to the theater] when you act… you don’t even know what you have done.”

Beyond the aforementioned cameo in Roma, her last film role is next to Marcello Mastroianni in Alfredo Giannetti’s Correva l’anno di grazia 1870 (1972). The umpteenth coincidence in a life that is itself a film, the movie’s broadcast is on the evening of September 26th, 1973: just a few hours after, Anna passes away from pancreatic cancer at the age of 65.

The list of reasons why we love and why we have been missing Anna Magnani for 50 years could never be exhaustive. And having in our hearts the magnetism of her eyes, admiration for her coherence and gratitude for her fragility, we will find ourselves again singing the notes of Pino Daniele: “Anna verrà e sarà un giorno pieno di sole e allora, sì, ti cercherei, forse per sognare ancora, sì, ancora…” (“Anna will come and it will be a sunny day and then, yes, I will look for you, perhaps to dream again, yes, again … “).