“If the architecture is any good, a person who looks and listens will feel its good effects without noticing,” said architect and designer Carlo Scarpa (1906–1978), and perhaps this is why Venice feels the way it does. One might think it’s the patina of empires past—the golden domes, the Gothic arches, the grandeur at every turn. But some of its most quietly stirring “good effects” comes thanks to Scarpa himself and his mid-century modernism. A steel-and-wood bridge beside a centuries-old stone one; a glass panel that reframes a Gothic window; a concrete stairway that feels like sculpture: Scarpa worked across museums, gardens, palazzos, and even cemeteries—each project a study in how modern design can coexist with, and even enhance, the historical fabric of the city.

Though he designed over 50 projects across Italy and abroad, it was Venice—its light, its materials, its natural water features—that most profoundly influenced his work, and whose visual identity he helped shape in return.

Venetian by birth and raised in Vicenza, Scarpa is rightly recognized as one of Italy’s most important architects of the past century. After studying at the Reale Accademia di Belle Arti, Scarpa received his first independent architectural commission at just 19. He would go on to be best known for his restorations of historic museums—a task that many of his contemporaries dismissed as “too constrained by the past.” Yet, innovative as ever, Scarpa’s work is a breath of fresh air amidst the era’s brazen glamor, and he’s had an even greater long-term effect on La Serenissima than those who pined after fleeting, flashy modernity.

From the get-go, it’s apparent that Scarpa’s architectural vision went beyond practical solutions; he dove into his subjects like a curious scholar, playing with materials like cement, Istrian marble, gold, and water—his favorite—in his designs. Though the Venetian was particularly inspired by his city’s Byzantine mosaics, his biggest inspiration came from another water-surrounded place: Japan. He fell in love with harmonious, simplistic Japanese forms while traveling, and was equally inspired by big names like Frank Lloyd Wright (who returned his adoration), Mondrian, Albers, Rothko, and Josef Hoffmann. It’s no surprise that Carlo Scarpa emerged as a bona fide Renaissance man of the last century—though “he wasn’t one to worry about his legacy or the enduring purity of his creations,” writes Nancy Hass in The New York Times Style Magazine.

As an art historian who’s spent a decade focusing on the Renaissance art of Venice, I’ve written hundreds of thousands of words on Venice’s art (quite honestly). And as much as I can (and love) to take anyone on a tour of Renaissance masterpieces dispersed across Venice, Carlo Scarpa’s architecture more often than not guides my meanderings; the city lays claim to the highest number of his projects, after all.

Here is Carlo Scarpa’s Venice. While I could’ve certainly chosen more examples of his work, Scarpa had a lifelong fascination with the number 11—which happens to be the number of letters in his name (though he never gave a real explanation for his love of the double-digit).

We’ll start our tour in the epicenter of Venice: Piazza San Marco.

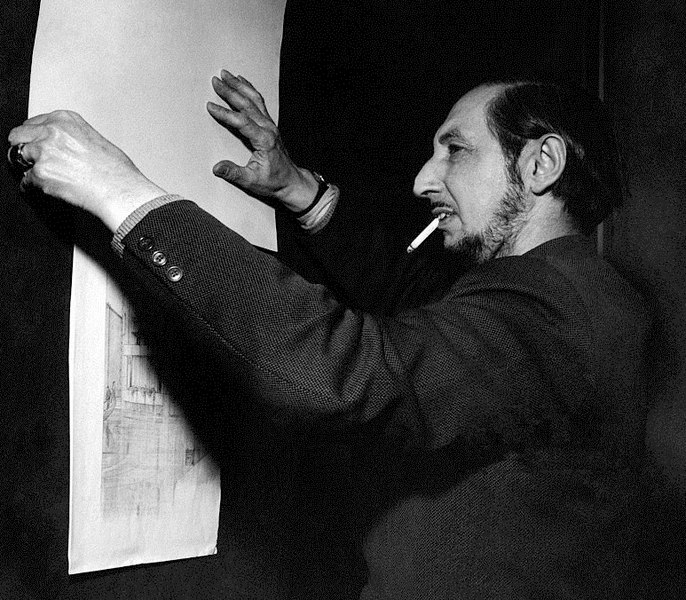

Scarpa studying the drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright, while smoking a cigarette (Venice, March 1954)

1. Olivetti Showroom (1957-1958)

If there’s one place to get acquainted with Carlo Scarpa, it’s here. The Olivetti showroom—which houses a collection of the eponymous typewriters—occupies a corner site among a row of shops and restaurants under Piazza San Marco’s colonnades. The slightly futuristic space is surprisingly bright, tucked as it is beneath the porticoes, thanks to full-length glass windows. Inside feels somewhere between an exhibition space and a high-end fashion store, where each typewriter is displayed like a prized sculpture or Birkin bag would be. A marble-slab central staircase seemingly floats between the showroom’s two floors.

Scarpa used a range of materials that had become his signature: Aurisina marble, stainless steel, rosewood, and cement, with mosaics and gold tying back to Venice and the piazza. These geometric gold accents adorn the walls, guiding your eye through the space. The trellis doorway leads to a striking red mosaic floor, with different spaces of the showroom tiled in blue, yellow, and white. Now under the protection of FAI, you can visit with a donation.

Negozio Olivetti; Photo by Victoria Huisman

2. Museo Correr (1952-1960)

Some of Scarpa’s best work was his visual and spatial renovations for museums and galleries. A great example is just across the piazza from the Olivetti showroom: the Museo Correr, a civic museum with rich and varied collections of Venetian art.

In 1952-53, he remodeled the rooms of Venetian History on the first floor, and in 1959-60, the Picture Gallery on the second floor. For these remodels, Scarpa’s approach moved away from traditional gallery displays and treated the works in the collection as sculptural elements in their own right. With the eye of a curator even more than an architect, he placed sculptures on cantilever steel mounts and paintings on rosewood easels at right angles to the walls, as if they were returned to the artists’ studios. In nearly all the rooms, he painted the walls white, continuing to direct all the attention back to the individual artworks. His sensitivity to materials and contexts call attention to Rationalist principles, popular in Italy in the ‘20s and ‘30s.

Documentation of Scarpa's renovation at Museo Correr from 1961; Photo by Paolo Monti

3. Giardini della Biennale (1948-1956)

Scarpa designed three mainstay architectural projects at the Giardini for the Biennale. Though no longer in use, the ticket booth perhaps most demonstrates Scarpa’s ability to draw inspiration from his hometown, with a symphony of sinuous curves cast in cement and a cantilevered wooden cover shaped like a boat’s hull.

The sculpture garden Scarpa designed for the Central Pavilion in 1952 has a similar boat motif. A concrete roof, suspended on ovoid columns, creates a balance between suspension and gravity—plus offers shade, essential on hot summer days—under which a shallow fountain spits up three thin spouts.

Scarpa crafted the Venezuela Pavilion (1954), his third project at the Giardini, with deliberate austerity, using rough concrete and a bold geometric form. The harsh facade is slightly softened by elongated windows on the second floor, plus small details like gilded brackets on the exposed piping and wooden aspects like latticed doorways, elevating the structure beyond its coarse, functional appearance.

Biennale sculpture garden; Photo by SEIER+SEIER

4. Monument to the Partisan Woman (1955)

Though not part of the Biennale complex itself, this monument—set on the riverbank of the Giardini—presents as an extension of Scarpa’s work for the event. The focal part of the sculpture is a statue of a lonely reclining female by Augusto Murer (1922-1985), a tribute to the Italian women who fought against Fascism. Scarpa was later tasked with designing a way to better showcase the statue. He had clear aims: a peaceful space away from main thoroughfares with a seamless balance between the water of the Lagoon and the greenery of the Giardini. To create a base, Scarpa drew reference from the Venetian technique of ramming wooden trunks into the mud of the lagoon. Instead of wood, he cast the squares from white Istrian stone atop concrete, arranging them in a geometric pattern at varying heights—they appear to be undulating, as if moving with the tides—and balancing Murer’s bronze sculpture on top.

Scarpa’s plan, and genius, becomes apparent when the tide washes over the monument. Sometimes, the Istrian stone is completely obscured by the water, and other times, it’s slowly revealed by the lapping water. What Scarpa didn’t account for, however, was that rising sea levels would impact the Lagoon. Over time, the monument has eroded, the Istrian stone darkened and worn. Though this may be an unfortunate implication, it fully connects Scarpa’s work to the “material” of water, and by extension, Venice.

Monument to the Partisan Woman; Photo by SEIER+SEIER

5. Fondazione Querini Stampalia (1959-1963)

If the Monument to the Partisan Woman manifests water’s corrosive power, the Fondazione Querini Stampalia harnesses water’s potential. Founded by Giovanni Querini Stampalia, the Fondazione occupies a palazzo that houses his personal art collection and a library of over 400,000 volumes.

Unlike at the Museo Correr, Scarpa’s work here focused not on the galleries but on the entrances and garden. For the pedestrian entry from Campo Santa Maria Formosa, he designed a steel and wood bridge, anchored by white Istrian stone slabs. Compared to the neighboring traditional stone bridge, Scarpa’s is strikingly thin and light.

For the waterside entrance and portego (dock), Scarpa subs out the traditional wooden doors with iron gates: at aqcua alta, the water floods in, lapping over and submerging the jetty he created from irregular stone steps. The steps ascend to reach a suite of galleries, navigated by rectilinear channels, with walls paved in stone and flecked with gold. During acqua alta, the water in the lower jetty creates mesmerizing reflections on these walls.

Drawing from Japanese and Islamic design, the garden reflects an appreciation for water—this time, with a desire to tame it. The babbling metal and stone fountains flow through the space like geometric snakes cutting through the undergrowth. This sense of the “untamed” is accentuated by ivy climbing across the walls. The mosaic of gold, silver, and black Murano glass grounds the space in Venice. As one of the few public gardens in Venice, it’s worth sitting here for a few minutes to contemplate the complexity Scarpa created in such an intimate space.

Fondazione Qurini Stampalia; Photo by Victoria Huisman

6. Tomba Capovilla (1943-1944), Isola di San Michele

Any visit to the Cemetery of San Michele feels like a pilgrimage—the island exists solely as Venice’s resting place for the dead. Scarpa communicated the island’s naturally sombre air in his second funerary monument, commissioned by the Capovilla family. The eponymous Tomba Capovilla is a tall, slender slab of Botticino marble tombstone. The elongated shape evokes the grace of an angelic figure, with two wings that curve around the ashes, encased in a vertical container at the top of the monument. On the facade is a simple relief of the Deposition of Christ that was once owned by the Capovilla family. At the base lies a small flowerpot. A poignant, yet simple, memorial.

Photo by Duncan Gibbs @duncan.gibbs

7. Ca’ Foscari & Aula Baratto (1935 & 1955-1956)

In 1935, Scarpa was invited to take part in the renovation of his alma mater, Ca’ Foscari. Housed in the 15th-century Palazzo of Doge Francesco Foscari, the university offered a historic framework: to highlight the Gothic trellis columns of the balcony overlooking the Grand Canal, he introduced a wide, wood-framed glass window across the piano nobile, filling the space with natural light.

Then, in 1955, he was commissioned for further work to the Palazzo, including transforming the Aula Barratto into a lecture hall. He removed the tribune and installed glass paneling with wooden shutters, creating an enclosed space that felt much more like a lecture space than a grand hall—another example of how he masterfully moved and directed light through a space.

Aula Baratto; Photo by Andrea Avezzù via Flickr

8. University of Architecture of Venice (IUAV) Entrance (1968-1978)

If there was a moment’s hesitation in including IUAV in this Scarpa tour, it is because of the “interventions” (read: graffiti) that opportunists have made to this design in the years since Scarpa completed it. It may now look a little forlorn from the exterior, and though it’s a piece of truly functional architecture, that doesn’t dimmish its complexity. The massive façade is crafted from a slab of Istrian stone, engraved with IAUV, suspended on a pulley system. A slab of concrete rests at a near 90-degree angle to the ground, under which students walk along a long, simple corridor to the university’s entrance.

Concrete is again central, and here it best demonstrates Scarpa’s use of this material to play with light and shadow. At the façade, there is a play of cascading steps, and at the entrance to the building, cement steps in a sunken pool create the illusion of water flowing over them.

IUAV entrance; Photo by SEIER+SEIER

9. Gallerie dell’Accademia (1945-1959)

This Italian state museum holds the finest collection of Venetian and Veneto art, especially paintings from the 14th to 18th centuries, and is housed within the former complex of the 13th-century Church of Santa Maria della Carità. Converting the space into a museum came with its own set of challenges—ones that curators had grappled with since it first opened to the public in 1817.

Scarpa joined the evolving project over a century later, with a 15-year involvement shaped by curatorial needs. He reconfigured the galleries to allow for easier flow, replastered the walls in traditional lime, and designed sleek metal and wood supports for the paintings (that are admittedly less evocative than those at the Correr).

Scarpa’s son, Tobia Scarpa, followed in his father’s footsteps as an architect, and in the perfect father-son enterprise, designed the Palladio Wing on the ground floor, which opened in 2015.

Documentation of Scarpa's Gallerie dell’Accademia renovation 1963; Photo by Paolo Monti

10. Stanze del Vetro, San Giorgio Maggiore

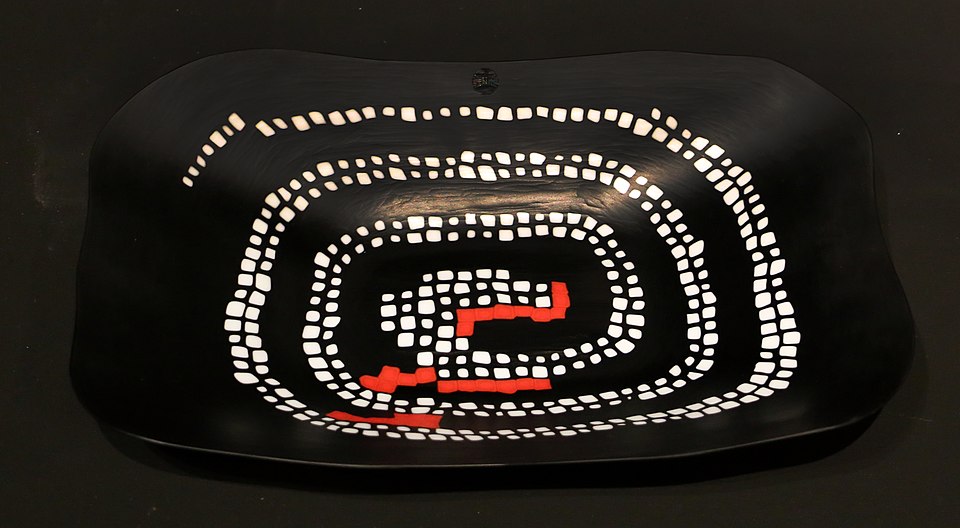

Scarpa’s career actually began not in architecture but in glass—a fitting origin for a Venetian. In 1927, he started designing for Capellin & Co., and by 1932 had embarked on a 14-year collaboration with Venini. For the company, he pushed the boundaries of glassmaking, inventing new forms and techniques that often flirted with the impossible. Consider his 1961 polyhedral chandelier, a cascading stalactite composed of over 4,000 individual glass pieces, or his development of murine-opache, a method that gave glass the tactile appearance of ceramics.

Aside from a handful of examples at the Ca’ Pesaro, few of Scarpa’s glassworks remain in public collections. On rare occasions though, his glass creations can be admired at exhibitions held at the Stanze del Vetro on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. The next one, 1932–1942: Il Vetro di Murano e la Biennale di Venezia, will run from April 13th to November 23rd, 2025. It explores how the Biennale served as a platform for designers like Scarpa to showcase their work to an international audience and how, in return, the Biennale helped shape and inspire Scarpa’s creative evolution.

Piatto Serpente (1940) for Venini, on display at Triennale Design Museum; Photo by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons

11. Brion Tomb, San Vito d’Altivole (1968-1978)

The final stop on my guide to Scarpa’s Venetian vision is a bit of a cheat, as it’s not located in the city, but on the mainland just outside Treviso. Yet if there is one journey outside Venice that’s worth making on a Scarpa pilgrimage, it’s this one. In 1968, Scarpa was commissioned to design the Brion Tomb as a private cemetery for Onorina Tomasin-Brion and her late husband, Giuseppe Brion. It would also become Scarpa’s own final resting place of choice. Rather ironically, this was his last project that he completed before his premature death, following an accidental fall down a flight of cement stairs in Japan in 1978.

A swan song par excellence, the Brion Tomb brings together, almost without fault, every architectural and design element that Scarpa engaged with throughout his career: cascading concrete steps, meticulous mosaics, the control of water, and golden accents. The tomb extends over 2,000-square-meters and encompasses a suite of concrete buildings plus a garden. The most recognizable feature is his venn diagram-esque windows, allowing sunlight into the otherwise dark, somber space. On par with much of his architecture, it’s intended less as a tomb and more as a place for reflection, as visitors are encouraged to meander through the spaces, from the chapel (inspired by Japanese tea houses) to the garden by cutting across the surrounding pond via stepping stones.

The overarching sentiment of peace and harmony comes from Scarpa’s fusion of Japanese and Venetian references, once again using water as a great unifier. This tomb is, quite simply, a masterpiece that has to be experienced to be understood. The epitaph in the garden that marks Scarpa’s final resting place reads simply: “A man of Byzantium who came to Venice by way of Greece.” Simplistic this may be. But how else to contain the genius of Scarpa’s work in just a sentence?

Tomba Brion; Photo by SEIER+SEIER