In the winter, all the lemons in Amalfi have already been picked, and the empty lemon arbors glisten in the freshly fading dawn. With that slowness typical of certain southern villages, first stores lift their shutters: within an instant, the bustle of tourists already invades the alleys of the center.

The last and only paper mill still active in Amalfi slowly churns to life too. The mill’s owners, the Amatruda family, have carried on the tradition of papermaking since the 15th century. Formerly a hotspot of the papermaking craft, Amalfi was hit by a devastating flood in 1954, destroying 13 of the 16 paper mills and crashing the paper industry. Today, just one of the surviving three remains: the Amatrudas are the only family residing in Amalfi that continues to produce paper in the town itself. Cartiera Amatruda–in the Valle dei Mulini, the innermost part of the town–is built on several levels along the Canneto River. And in Amalfi, paper is, quite literally, a calling card: the mill’s fine production dialogues perfectly with a town whose locals, artisans and shops can all be found using Amatruda-branded paper.

Photo courtesy of Cartiera Amatruda (@amatruda_amalfipaper)

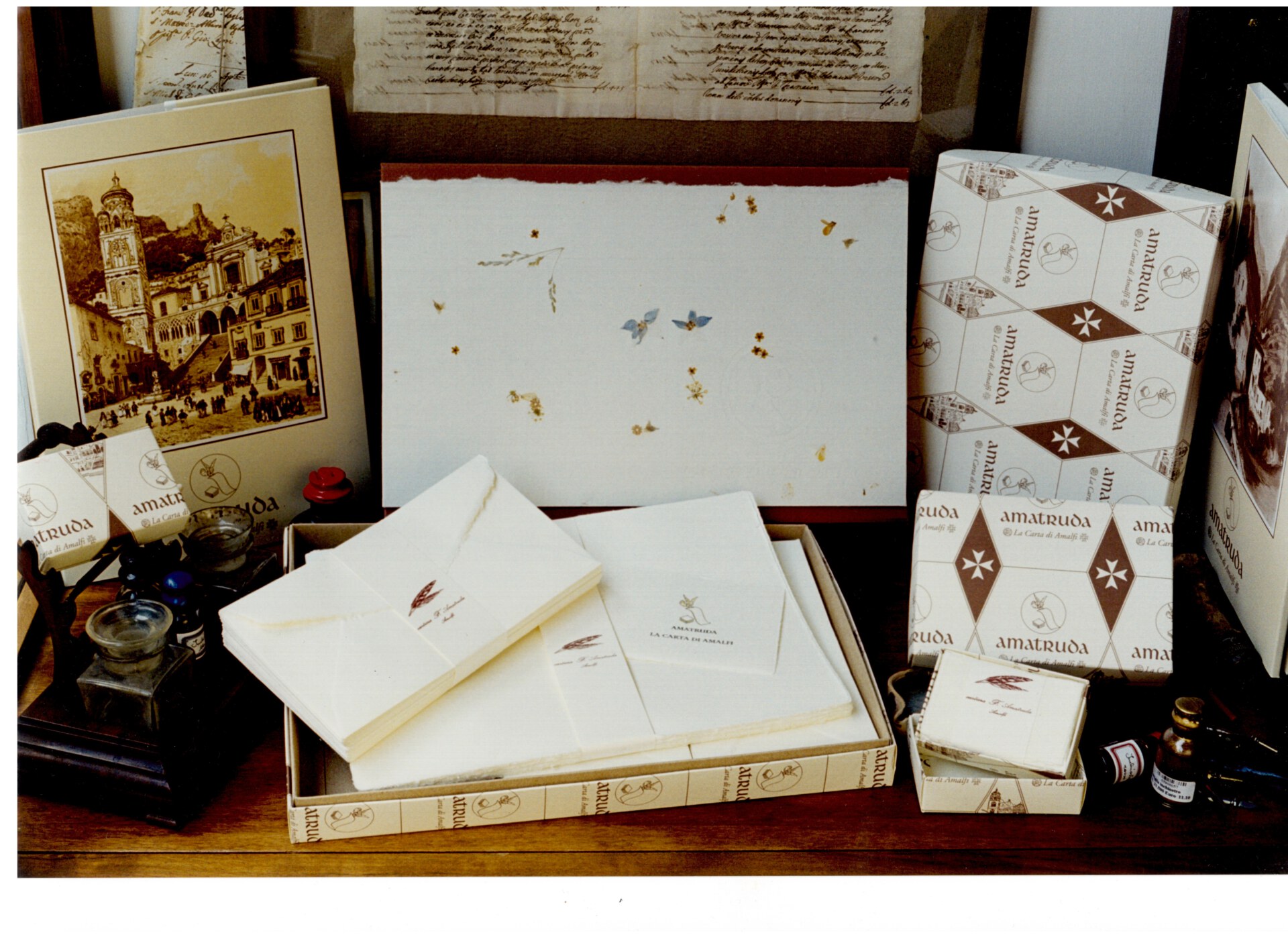

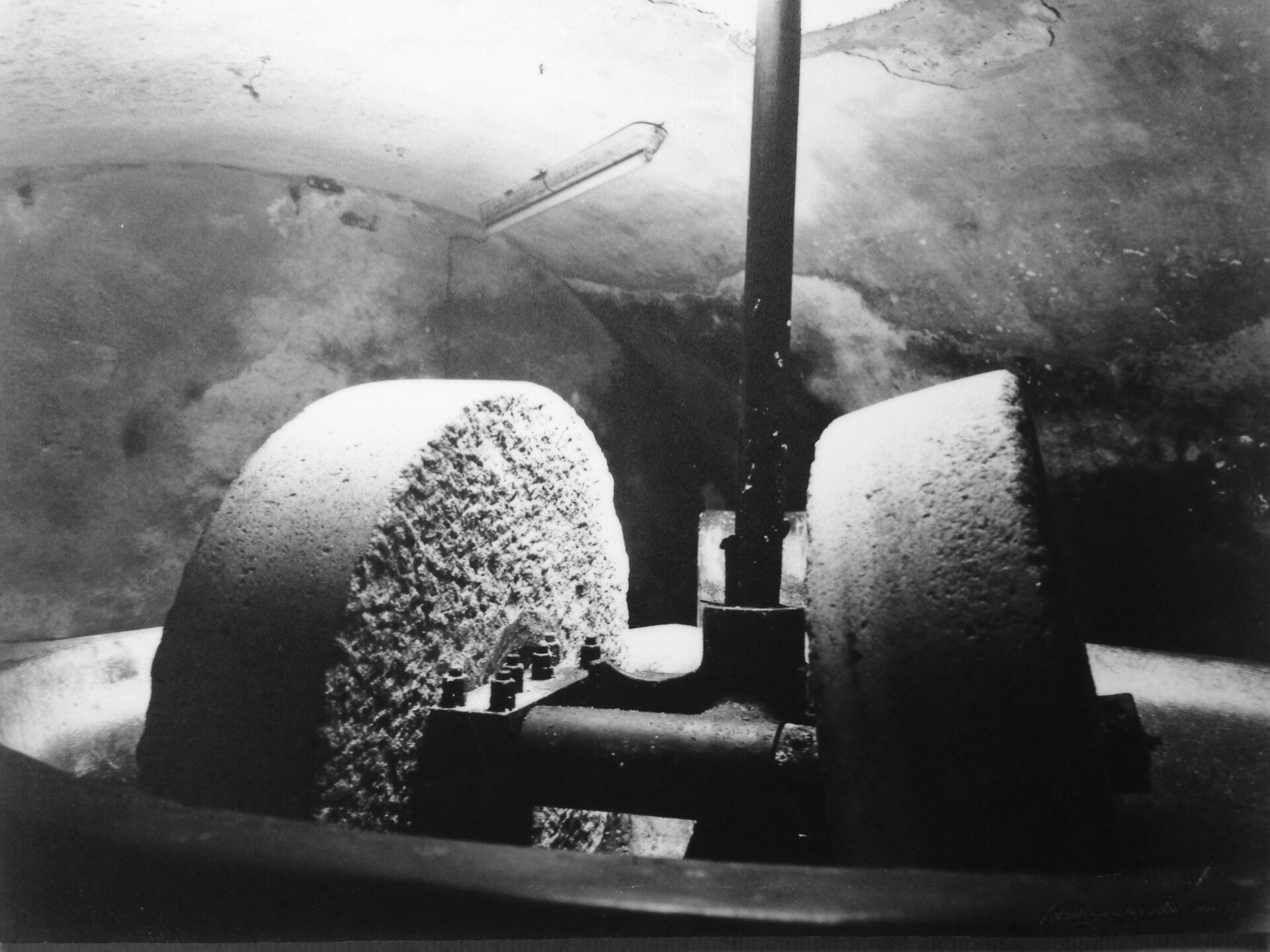

In Amalfi and elsewhere along the coast, rag paper, also known as bambagina, has been made since the 13th century. An ancient maritime republic, Amalfi was one of the first places to produce paper in Europe–thanks to the countless trade routes with the Arabs, who learned the technique from the Chinese. The Amalfitans learned to exploit new resources, water in particular, and were among the first to realize the importance that paper could have. The rags, generally from cotton or linen cloth, are bleached, shredded and mixed with water; they are then ground, reduced to a pulp into which the form (a cloth with a wooden border and a watermark in the center) is dipped. The watermark is crucial in distinguishing the different papermakers and the type of paper produced: the Amatrudas’ depicts a coat of arms with three Angevin fleurs-de-lis, evidence that the family was already making paper during Angevin rule in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1282-1442).

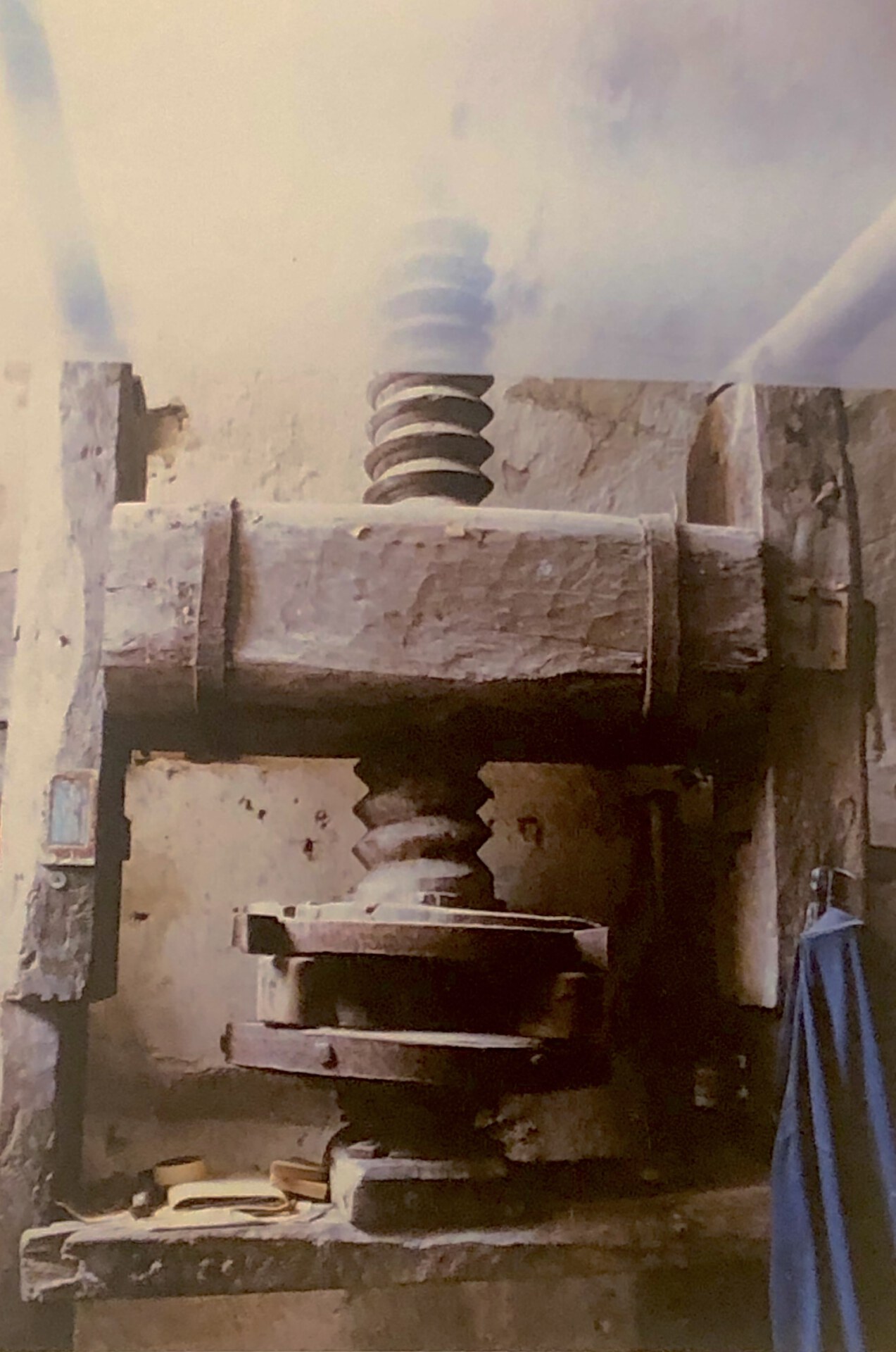

From the form, the pulp is transferred onto felt cloths and stacked into a pile in which the sheets of paper alternate with the felt. Next, the stack is pressed to remove water. The drying stage, before the sheets are smoothed and carefully checked one by one, takes place in the spandituro, the highest part of the paper mill: here, the presence of large windows, therefore air drafts, ensures that the sheets of paper hung on long iron wires dry completely.

Photo courtesy of Cartiera Amatruda (@amatruda_amalfipaper)

It is one of the artisans, Michele, who welcomes me into Cartiera Amatruda and takes me, room by room, through towering stacks of sheets, notebooks, tickets and stationery, pointing out five-hundred-year-old machinery that is still in working order. “There are no computers here,” he says, “It’s all done by people. We are few in number. Even those who aren’t named Amatruda feel like family.”

Paper is handmade daily–the way it has been for more than 700 years–at the mill, today helmed by the young Giuseppe, part of the latest generation of the historic family. After the cloth is dipped in the paste, the work is done by the movement of the wrists, the touch, the manual skill. Witnessing the extraordinary process that leads to the creation of a single sheet of paper puts into perspective the value and excellence of this craft. We consider paper to be disposable, but it’s the first ingredient of any grocery list or novel, of any “Dear Diary”.

Luckily, the Amatruda paper mill has a small, but worldwide market and exports wedding invitations, bookmarks, business cards, painting paper and more to those who appreciate the hard work and quality of this ancient craft. Also very special is the paper with flowers, made by dipping fresh flowers, picked in the valleys around the paper mill, into the paste in which the form is dipped.

As I move from room to room, I take in the hum of the machines, punctuated by the gestures of the workers, and the damp, hard-to-put-to-words smell of a newborn sheet of paper. Between these columns of sheets reinventing architectural principles, time stands still, and all trace of the world outside is lost. In the topmost room, the one used for drying, a sort of old-fashioned clothesline runs along the ceiling, but it’s not clothes drying in the sun (light fails to creep in here), but writing paper–the newest batch of blank slates.

Photo courtesy of Cartiera Amatruda (@amatruda_amalfipaper)