Langa, in Piedmontese, means “hill”; Langhe, in Italian, defines one of the world’s best-known territories when it comes to wine and cuisine. Today, however, “Le Langhe” has become a plural concept that encompasses the history of Italian wine, both past and present, as well as emerging brands.

Looking on the map, we are talking about a hilly area between the Tanaro and Bormida valleys, between the provinces of Asti and Cuneo. To describe it to a foreigner who thinks on other scales, I would have to say between Courmayeur and Portofino; to get into the merits of this all-Italian story instead, you need to use a microscope and hold a map in your hand. Today, Le Langhe, along with Roero and Monferrato, are often mentioned all together because they have been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for their special wine-growing landscape and cultural traditions related to viticulture, but they have distinct identities with each other, and even within themselves. It is a game of Russian dolls and overlapping borders, difficult to understand even from just a few valleys away, but it says a lot about the wine and the economy of these lands.

Le Langhe Made in the 90s

In total, the UNESCO territory has just over 10,000 hectares of land, a third of the size of the Champagne region, but if we talk about the Langhe del Barolo, the most famous area, then we can squeeze it down to just over 3,000 hectares. The Langhe of Barolo, Barbaresco, and the White Truffle of Alba (and Nutella), are the best known and became famous in the late 1990s thanks to the great reds historically vinified among these hills. They are the destination of wine pilgrimages and gastronomic tours in elegant starred restaurants or aboard coaches for organized truffle-hunting trips. Over the years, one of the greatest examples of Italian food and wine tourism has developed here: wineries have become centers of attraction, haute cuisine has been leveraged, bed & breakfasts have sprung up just about everywhere, bottle prices have skyrocketed, and the vineyards of precious Nebbiolo have spread to occupy every free corner of the land. They have led the way. The landscape around the villages of Barolo, La Morra, Monforte, and Serralunga d’Alba is marked by neat, precious rows of vines, and they haven’t left room for anything anymore–not a vegetable garden, not a forest. These are just “Le Langhe” that today we could call “basse” (“low”) because of their altitude and because another territory is emerging that is, at the same time, a new toponymy: “alta” (“high”).

The New Concept of Alta Langa

Alta Langa is a nice concept: it sounds good, it suggests altitudes and purity. It is a definition that includes, depending on one’s point of view, a geographical area, a wine, a territorial brand, and a new perspective on tourism development. Looking on the map, Alta Langa is that area on the border with Liguria that occupies the highest altitudes, generally over 500 meters and up to 900 meters, where the hills are steep and the landscape is wild and less urbanized. It reaches altitudes that traditionally were not home to vineyards but to forests, goats, and hazelnut groves, and where, until the 1980s, you could even ski. Today in Bussolasco, the village of roses, the ski lifts are gone, however, and instead new resorts are being built, looking to the example of their “bassa langa” neighbors and uncorking a new wine with ancient roots, Alta Langa DOCG.

The Self-Determination of Alta Langa DOCG

It’s not red, and it’s not still. Alta Langa DOCG is a sparkling wine that follows the specifications of champagne in terms of production method and grapes. If the “lower” Langa is a land of increasingly hot reds, on the cooler high hills bubbles are produced, now more popular in global wine consumption. Climate changes, tastes change, and so does the geography of territories.

The idea is relatively recent: the “Metodo Classico Spumante Project in Piedmont” and the first experimental chardonnay and pinot noir vines in the area date back, in fact, to the early 1990s, the first bottle of Alta Langa to 1999. Today the DOCG is produced in 149 municipalities in the provinces of Asti, Alessandria, and Cuneo, starting from 250 meters above sea level and (for now) in less than 600 hectares of vineyards. I know, it’s complicated: Alta Langa is a territory, and Alta Langa DOCG is a wine, but the wine is also produced elsewhere, on a few hills in a larger territory not far away. The interesting thing is that the Alta Langa “brand” is making its way as a destination and travel idea, off the beaten path, beyond the monocultural landscapes of Barolo and Barbaresco. New addresses have embraced the promise, capitalizing on the name. There’s been a flourishing of freshly-opened residences, restaurants, dairies, and small accommodation facilities, all labeled “Alta Langa” because they have seized the opportunity in terms of marketing. After all, the principle of self-determination of peoples applies, even in branding choices.

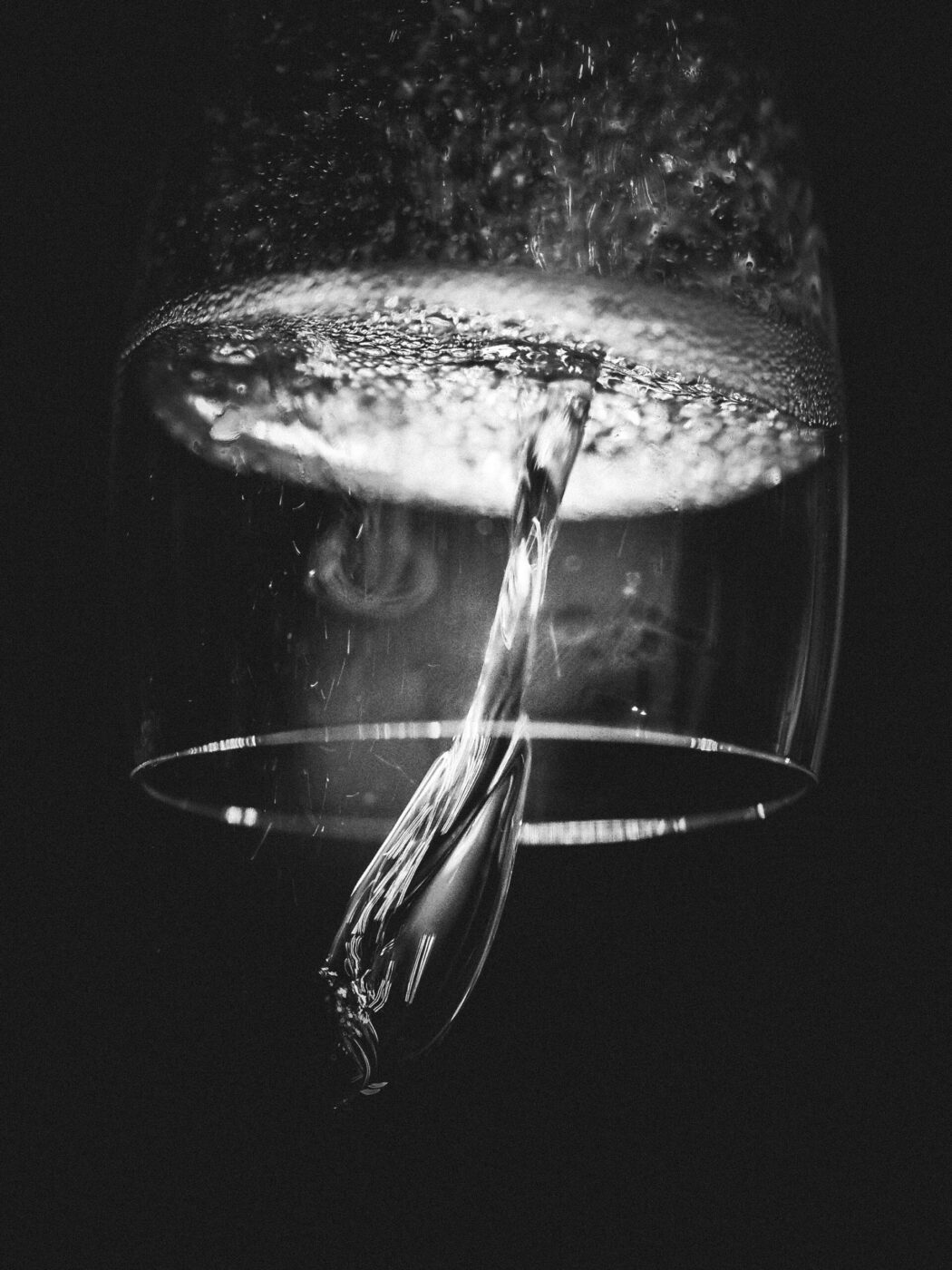

Riddling is the process of gradually rotating and tilting bottles of sparkling wine, typically at a 45-degree angle, to move sediment towards the neck for removal during disgorging, and a key part of the Champenoise method

Bubbles, Between Tradition and Innovation

The idea of Alta Langa (wine) proved to be a far-sighted strategy that 40 years later is rewarding the producers who believed in it first. The founding wineries of the project, “the seven sisters”, include names such as Cinzano, Contratto, Gancia, and Riccadonna–giants specializing in Moscato d’Asti, the first Italian sparkling wine, born a few kilometers away around the town of Canelli. Now one must take another leap back in time, to the early 19th century. The history of Italian bubbly has its roots right among the hills of Piedmont and owes its birthplace to Carlo Gancia, who in 1848 went to study in France and later in 1865 perfected the production of Italian sparkling wine using the “champenoise” method; he planted the first pinot noir in the area. To this day, these precious sparkling wines still rest for years in the pupitres of the scenic UNESCO World Heritage-listed underground cathedrals carved into the tuff hills of Canelli, a tradition they drew on more than a century later for the production of brut Alta Langa.

Rebranding Moscato d’Asti

The story would be philologically flawless if it weren’t for a recent history that’s very often left out in the story of Italian wine… Between the sparkling wines of the past and those of today, there is a whole parenthesis that has dictated the fate of local winemaking in terms of whites for years: that of the aforementioned Moscato d’Asti. The same historic cellars that have made the ancient and modern history of bubbles are also those that have laid the foundations for the industrial production of this wine, that from the 1960s onwards became extremely popular worldwide. Thanks to technical improvements, the production of this sweet and aromatic sparkling wine (not a brut like the Alta Langa) grows to the point of flooding the entire world and the shelves of supermarkets, with peaks during the holidays when it’s uncorked to accompany the also industrial panettone. (Even if this sweet bread is not its ideal pairing–light and fruit-based desserts are better.)

But tastes are changing, dry wines are market favorites, and massive production is no longer sustainable. At the turn of the third millennium, 100 million bottles of Moscato D’Asti required diversification, with the goal of enhancing a wine that risks being associated exclusively with low-priced popular bottles. Experiments began, dry and non-sweet vinifications, the search for greater quality, a relaunch of the brand’s positioning. Looking for new roads, the one of Alta Langa seems to be the one succeeding.

Gemma inside of Osteria Da Gemma

Here, a short list of places to eat, drink, and stay at in Alta Langa:

F.lli Gancia – Where it all began and where you can explore the history of Piedmontese bubbles. The visit to the cellars, one of the UNESCO World Heritage Underground Cathedrals, is beautiful.

Borgo Maragliano – This family-run winery was among the first to start experimenting with pinot noir. You’ll sip while overlooking the hills in the panoramic tasting room.

Casa di Langa – This design-forward eco-resort is where you can immerse yourself in 42 hectares of vineyards, and understand the new course of the territory from the point of view of hospitality.

Le Due Matote Relais – Find Campanian-style cuisine at this resort with a few rooms in Bussolasco, the Country of Roses. It’s the perfect starting point for a road trip complete with a picnic.

Trattoria Madonna della Neve – Founded in 1952, this restaurant is a thing of myths in the area. Locals come here to eat agnolotti del plin served without sauce, on a linen napkin, and great meat-based secondi.

Osteria da Gemma – This €34 fixed menu features the now famous homemade pasta by Mrs. Gemma. It’s an institution of Piedmontese gastronomy and perfect for lunch. It’s basically always booked up four months in advance. (Find Italy Segreta’s feature on Gemma here.)