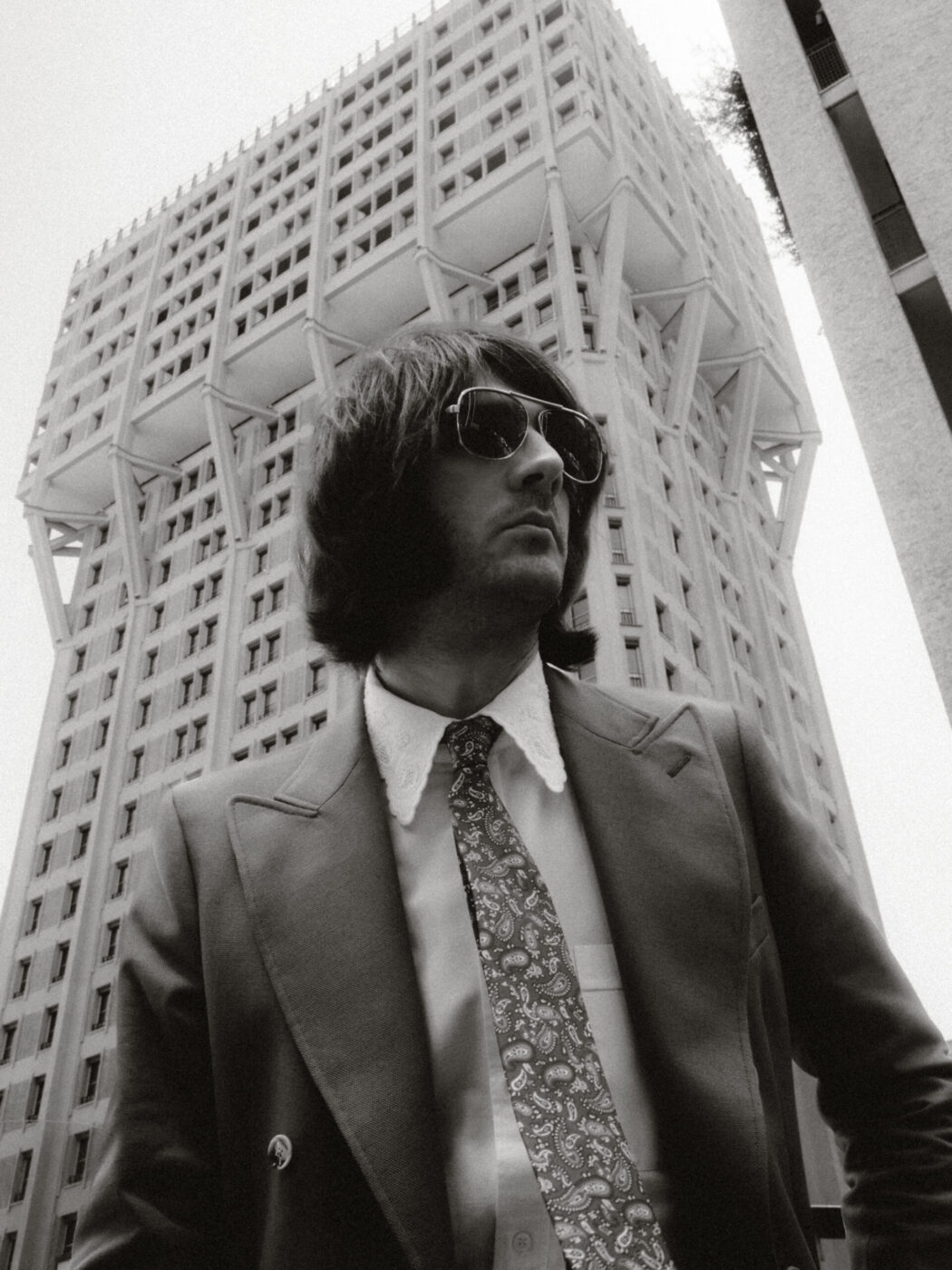

On the final day of June, Milan was a muggy 37°C. The streets around Torre Velasca—the Brutalist, Studio BBPR-designed tower rising above the Missori metro—were nearly empty, the air thick with heat and exhaust. But Alberto Bazzoli arrived for our interview looking impeccably composed: a paisley tie cinched at the collar of a scallop-edged, lace-trimmed white shirt, flared jeans skimming the pavement, a soft green jacket slung casually over one shoulder. On his fingers, two chunky rings—one bearing an “A,” the other a “B”—caught the pitiless sun. He looked less like the modern Milanese and more like the lost fifth Beatle—sweat be damned.

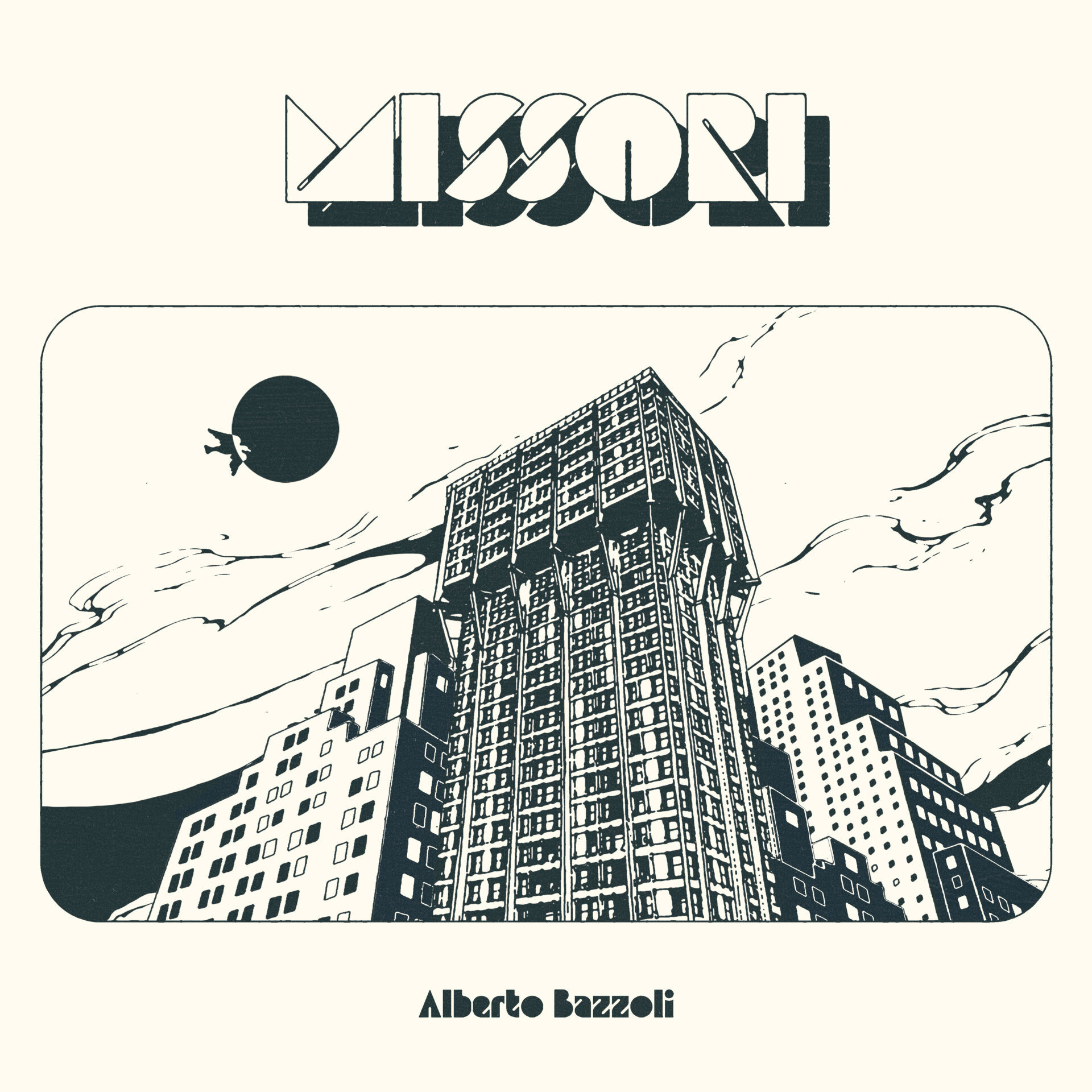

Fittingly, the striking Torre Velasca wasn’t just our rendezvous point: it’s also the cover star of Bazzoli’s new concept album, Missori, a tribute to the city that unfolds in its shadow. Entirely instrumental, the album follows a fictional white-collar worker wandering through the habits and hauntings of Milan. Bazzoli is quick to clarify he’s not the office worker in question, but “it comes from emotions I’ve really felt.” Across eight lush, impeccably arranged tracks, Missori channels ennui, nostalgia, and a dash of cinematic flair (that recalls the likes of Ennio Morricone).

Born in Bologna, the rising star cut his teeth in blues bands, co-founded the disco project Superpop, and more recently lent his keys to Baustelle’s albums Elvis and El Galactico. But Missori marks his first full-length solo album—a solo venture composed over several years as he settled into the city he’s come to call home.

Missori was recorded with an array of vintage instruments and analog techniques (the limited-edition vinyl even includes a complete list of all the old-school gear used on each track). A conservatory-trained jazz pianist and organist, Bazzoli has a well-known weakness for classic keyboards (he’s a devotee of the Hammond organ in particular). That love of vintage tone colors every note on Missori, from the mellow Fender Rhodes chords that add a melancholic tinge to swooning synth strings straight out of a ’70s film score. What elevates Missori beyond pastiche is its production; with producer Jolly Mare, Bazzoli has sculpted a sound that feels timeless, warm and analog in texture, but propelled by a crisp narrative flow and modern finesse.

Each of the album’s eight tracks plays out like a mini scene within this larger story. The second, “Patrizia,” for instance, arrives with a hopeful, romantic lilt (she’s “the stereotype of the confident Milanese woman,” Bazzoli tells us) and the jaunty “Tran Tran”—an Italian colloquialism that refers to what we might call “the daily grind” or “same old, same old” in English—nods to the drudgery of the nine-to-five. Meanwhile, the nocturnal cool of “Fuori Orario” evokes the city’s after-hours streets.

By the final track, “Refrain,” our imagined everyman seems to find a quiet epiphany—a realization that even an ordinary life in Milan, often pigeonholed as gray and cold (both literally and metaphorically), holds a special kind of poetry. And should any doubt remain, one need only flip the record back to side A, drop the needle, and let this urban daydream play on repeat.

IS: You were born in Bologna and later raised in Forlì, before moving to Milan. How did those places—particularly your adopted city—shape the emotional core and spirit of your music and Missori?

AB: That’s right, I was born in Bologna, but I grew up in Forlì until I was 19. I then moved to Bologna when I started studying at the conservatory. Milan, on the other hand, has only been my city for a few years, but it immediately influenced and inspired me. It allowed me to meet new and talented people to collaborate with professionally. Missori is about the relationship between a man and his new city, and with the memories of where he came from.

IS: You trained in jazz piano at Ferrara’s Conservatorio “Frescobaldi” and also honed your Hammond organ skills. Was that academic background what first led you toward the vintage-keyboard sound that dominates Missori?

AB: For sure, the jazz training made me a versatile musician, but at heart I’m a curious autodidact. Everything I’ve learned, and that shaped my style, I actually owe largely to personal experience—alongside my time at the conservatory—to the records I listened to and the musicians I met and spent time with.

The desire to start playing came spontaneously, listening to music as a kid—it was also a way to be with my friends at the time.

That said, especially in Missori, I brought in many of the skills I picked up at the conservatory, but in a distilled way, because I wanted to express all of my musically omnivorous self.

IS: Can you tell us more about the techniques you used to record Missori?

AB: All the tracks started as demos—some written in the early years after I moved to Milan, others from before. These sketches always had, in addition to harmony and melody, notes on instrumental timbres that I wanted to be protagonists, and that help give the piece its atmosphere.

I decided to actually make the album when I met Fabrizio Martina, aka Jolly Mare, who’s also the producer of Missori.

We began producing and arranging the demos together. One passion we share is vintage instrumentation, which you’ll hear used throughout Missori. That said, we always combine vintage instruments and methods with modern production.

IS: How did you develop the narrative of the office worker? Was it guided more by the music, the story, or the urban imagery?

AB: It’s hard to pinpoint exactly where it all started. For me, it’s a kind of cathartic process in reverse. I think I have a good visual intelligence, and often it’s through that sense that I find my way into music. Sounds, notes, harmonies organized a certain way give me embryonic images that come into full clarity only as I work on the piece—by adding colors. Like a sculptor who sees the statue in the marble, but only by carving does the figure fully emerge and become visible.

So to answer you: yes, I mainly wanted to make a record about the city of Milan, but it was the music itself that suggested the story to tell.

IS: Do you think of Missori as autobiographical in any way?

AB: The album is biographical in the sense that it comes from emotions I’ve really felt, but I’m not the office worker with the briefcase. I’m an observer—I like watching people and imagining things. I like living in made-up, imaginary worlds, and those emotions—I truly feel them, of course.

IS: What interests you about the mundane, the office, the pedestrian?

AB: I’m fascinated by the rituals of bourgeois civilization—which is disappearing.

IS: What do you mean by the “rituals of bourgeois civilization”?

AB: Bourgeois society, like all prosperous societies, created its own customs and traditions. These, which were part of many people’s childhoods—certainly mine—are now on the verge of extinction. Sometimes frivolous but full of charm and meaning, these rituals built an entire imaginary world.

Deeply wary of everything we call “new” and accept without filters, I love sifting through and analyzing recently faded worldly rituals: a recipe, a piece of clothing, a place of leisure, a table utensil. All these traces—fossils of vanished rituals, or at least emptied of their original meaning—have lost their sacredness in today’s society.

IS: How did you decide on titles like “Patrizia” and “Balcone con vista”—ones that evoke characters and scenes—to accompany the music?

AB: “Patrizia” is a fictional name. I’m a child of that old-fashioned tendency to name songs after women. The Patrizia of Missori is a bourgeois woman walking the city center streets with coral necklaces. For me, the name fits perfectly with the stereotype of the confident Milanese woman—part faded nobility, part bourgeoisie.

“Balcone con vista” is instead dedicated to my apartment’s balcony, which is on the sixth floor. It’s a kind of urban horizon I wasn’t used to: I look out and see the city, but also small houses with laundry hanging out and ringhiera-style balconies, very Celentano. That view is my version of Leopardi’s hedge.

IS: Missori nods to vintage Italian soundtracks (Morricone, Umiliani) and 70s‑style music, but it also feels modern. How do you balance nostalgia with originality in your creative approach?

AB: I like working with instrumental music because it’s so out-of-fashion that you’re truly free to make disparate musical associations. But I don’t like slavishly reproducing the past—I love translating it into real life. For years I produced music using the exact same recording chain as in the ’60s and ’70s, without using computers. From that experience, though, I learned that for who I am, and for the musical result I want, it’s important to use period instruments without giving up the convenience and speed of modern tools—because we’re in 2025, not 1970.

Back then, pieces were recorded live with fewer instruments. In Missori there’s more musical layering and more production.

IS: Speaking of, Missori feels like a soundtrack in search of a film. If it were one—what would that film look like? Who’s directing it?

AB: It would be a vaguely neorealist film, in black and white, directed by Alberto Sordi or Mario Monicelli.

IS: Why did you choose the Torre Velasca as the visual emblem for Missori? What drew you to the building?

AB: I’m a huge fan of architecture and I think Torre Velasca is a beautiful structure. It’s also a symbol of the Missori neighborhood in Milan, so it directly ties into the album title.

IS: What was it like stepping inside the tower for the first time?

AB: My perception was similar to that of other monuments of that scale and height: from the outside, our senses can appreciate it in its full aesthetic form, but inside, we get lost in a space that’s hard to navigate. Having a recording studio at that altitude would truly be a dream!

IS: Before this, you released L’Organo Ep. 1 in 2020, and worked with Superpop and Baustelle. After those experiences, why did you decide that Missori should be your first full-length concept album? Why now?

AB: My main activity is being a pianist. And a pianist spends most of his time in service of others. I had never taken the time to work on my own material—I’ve always worked for others. But playing with others is essential for me, because it gives you new inspiration.

With L’Organo I made a first attempt at solo production, but only now do I feel I can express a more varied complexity in a clear and ordered way.

IS: What do you want someone listening to the album to feel?

AB: Feeling good. Feeling in the right place for that music.