Rome: January 2nd, 1958. Italian high society is gathered inside Rome’s Teatro dell’Opera for its opening night: Bellini’s Norma is on the bill.

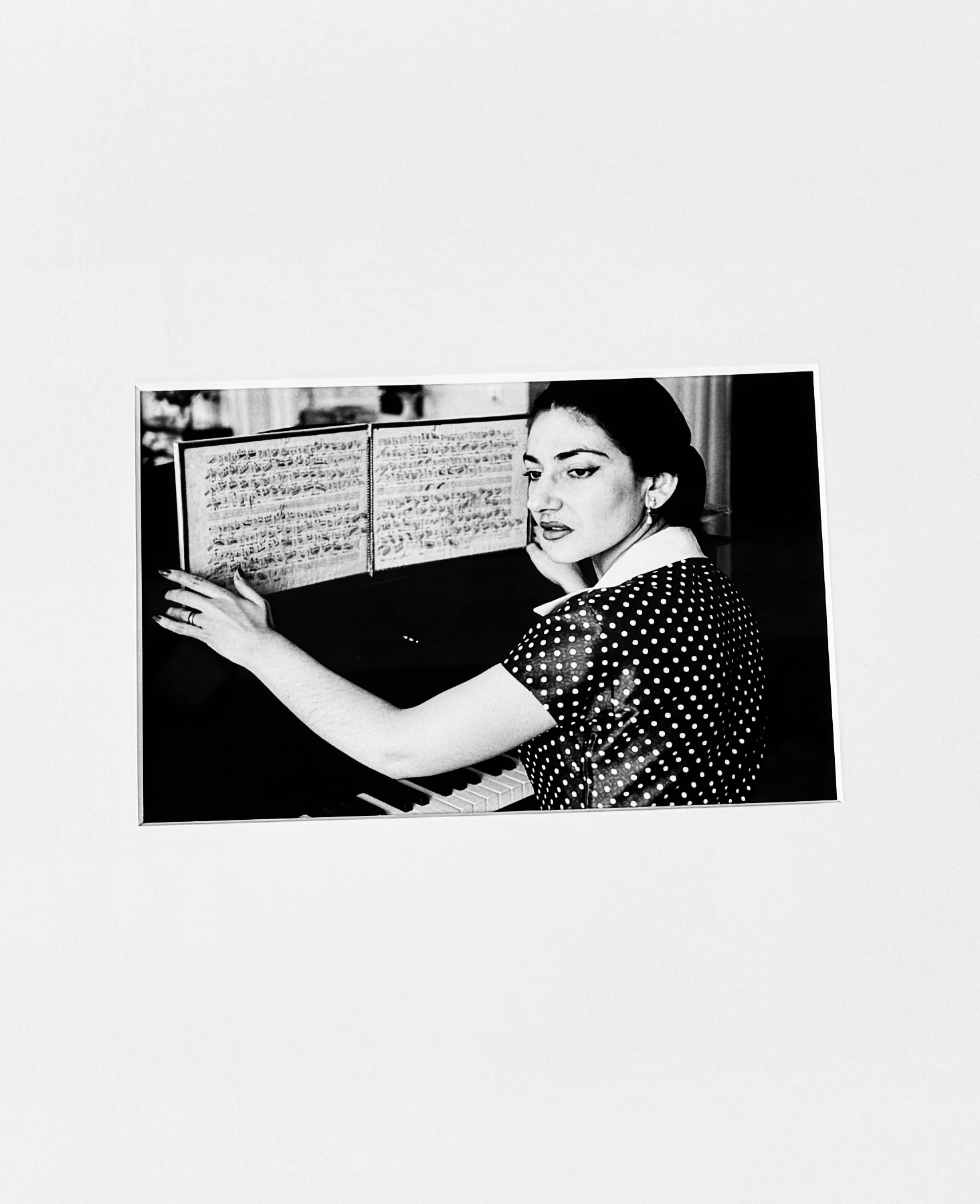

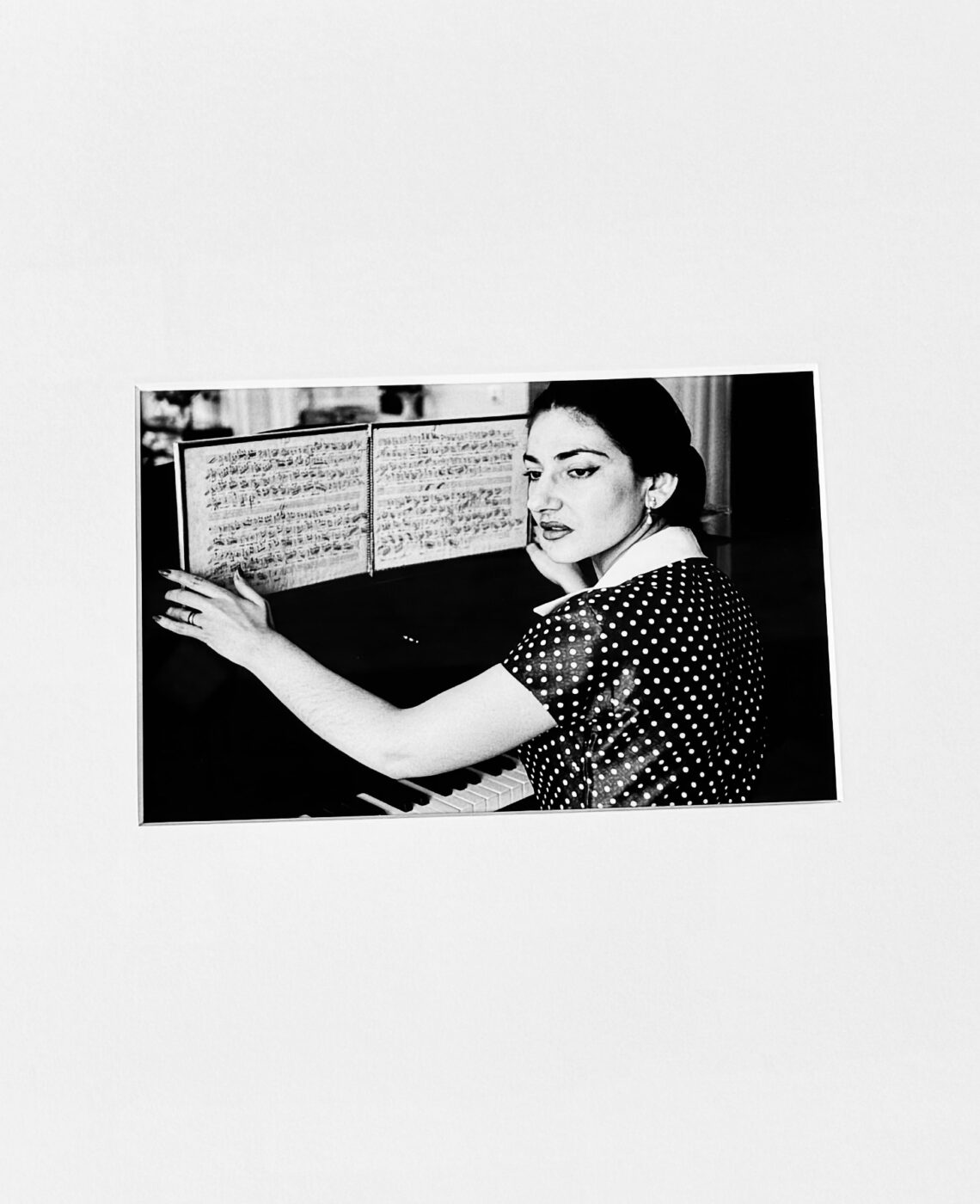

The glittering audience–3,000 viewers, among them aristocrats, diplomats and artists–includes the Italian President Giovanni Gronchi, the painter Giorgio de Chirico, and actresses such as Anna Magnani and Gina Lollobrigida. Everyone has come to listen to her, la Divina: Maria Callas.

The famed soprano is at the apex of her career, although deep inside she knows her voice has started to become wobbly. To make things worse, tonight she’s unwell.

Callas has severe tracheobronchitis (a respiratory tract infection, no less!), and despite her doctors’ efforts to get her on stage, she’s weak and nervous. The day before she had alerted the theater they should be ready with a standby, but they wouldn’t listen: “No one can double Callas,” they replied.

Draped in a red cloak, the soprano manages to get through the first act, but her voice is slipping away. The unforgiving audience notices and doesn’t appreciate it; clapping turns into disapproving whistles.

Callas leaves the stage in tears, suspends the recital and barricades herself in her dressing room. Confusion overtakes the parterre. Behind the scenes, the theater’s management desperately tries to convince her to go back on stage. She shouts at them so loudly that she now completely loses her voice. She writes a note of apology with her eye-pencil, but the message will never reach her public, which is notified the show has been canceled an hour later by a rather dry announcement:

“Per cause di forza maggiore, la rappresentazione è sospesa.” (“Due to force majeure, the performance is suspended.”)

The theater sinks into pure chaos. The national radio interrupts its live broadcast of the recital, reporting on the “violent discussions between Maria Callas’ supporters and her detractors [in the balcony].”

A week after, TIME reports: “WE DON’T WANT CALLAS IN ROME! was scrawled over the posters. Said others, in tribute to Soprano Callas’ famed rival: VIVA TEBALDI! On Via Nazionale, before the Hotel Quirinale—where Callas stayed in her suite—truncheon-swinging police again and again charged shouting demonstrators. On the floor of Parliament, a Deputy introduced a motion that would bar Maria Meneghini Callas from all of Italy’s state-subsidized opera houses.”

The episode, known as the “Rome Walkout”, is still remembered today. More than anything else, it is a suggestion that opera is our national affair with drama, both on stage as well as in the stalls.

Considering Italians’ penchant for excessive displays of emotions, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that, at some point, we felt the need to bring our natural inclinations for histrionics to the stage: Bel canto is an all-Italian art.

As a passionate opera-goer, I know a recital won’t disappoint me if one melodramatic condition is respected: at the end, everybody on stage must die.

After all, sitting in the darkness for hours with only one chance to go to the toilet and get a snack must be repaid somehow. And the great maestri of Italian opera knew their public’s need for drama too well. Inspired by 19th-century literature, a realm dominated by men, the likes of Verdi, Donizetti and Puccini came up with the most intricate plots and countless ways to kill their characters–with special consideration to female roles.

Teatro La Fenice, Venice

It doesn’t matter if you’re the princess of the Chinese Empire or a destitute girl living in a run-down attic in Paris: at the opera, if you are a woman, you know you have to sing and to suffer for love.

Every Italian opera usually starts by introducing the lead female character, stuck in a toxic relationship or in a dysfunctional family (so bad that, in comparison, Beautiful’s Forresters look like a happy family).

By the second act, the plot has developed into the destruction of marriage vows, a forced wedding, an imprisonment, an abduction, a child torn from their mother’s arms–or a combination of the above.

The story ends with a fatal accident or illness (consumption, if possible, as befits any respectable 19th-century lady), a natural calamity, or, in the most famous operas, suicide. It’s here that Italian opera offers records of rare imagination.

Abandoned by her American husband, Madama Butterfly sticks to her country’s traditions, committing a dignified and overall understated seppuku (did you catch this hint to Jennifer Coolidge’s Tanya in The White Lotus?). Tosca witnesses the fucilation of her lover and jumps into the Tiber from the bastion of Castel Sant’Angelo. In the middle of a mystical delirium, Sister Angelica drunks a lethal potion, only to realize she’s committed a mortal sin. The Countess Maddalena di Coigny, who has witnessed the homicide of her mother and has watched her castle burning to ashes, is forced to live in hiding. She falls ill, and willingly takes the place of a prisoner sentenced to death.

Norma leaps into the flames of a pyre as a human sacrifice; Wally throws herself into the avalanche that has wiped her lover away; enslaved by the Egyptians, Aida seals herself up in the same vault where her beloved Radamès has been buried alive. When he discovers her, the two start singing about the joy of dying together, but she only lasts five minutes before kicking the bucket.

They say that art imitates life, but life may imitate art more often than we think. This was certainly true for Callas, whose sentimental life–scrutinized to exhaustion by the newspapers–ended up resembling those of the characters she impersonated on stage.

In 1957, when she met the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, both of them were still married to other people. The two started a complicated affair for which they divorced their spouses. Madly in love with Onassis, although he repeatedly cheated on her, Callas progressively abandoned the stage, hoping that one day she’d marry him. But the tycoon had other plans, and in 1968, famously went on to wed Jacqueline Kennedy.

Her voice definitely compromised, Callas spent her last years in isolation in her apartment in Paris, until a stroke took her prematurely at age 53. Speculations over her death were not long in coming. Once again confusing art and life, many believed that Callas had in fact killed herself out of her desperation for love, like many heroines of opera before her.

The moral of the story(ies): Never fall in love with the wrong man. And keep away from Ancient Egyptian soldiers and Greek shipping magnates, for god’s sake.