“O Madonna Mia!” It’s a phrase that far surpasses “oh my god” in Italian–fitting, considering this country’s reverence for the Divine Mother.

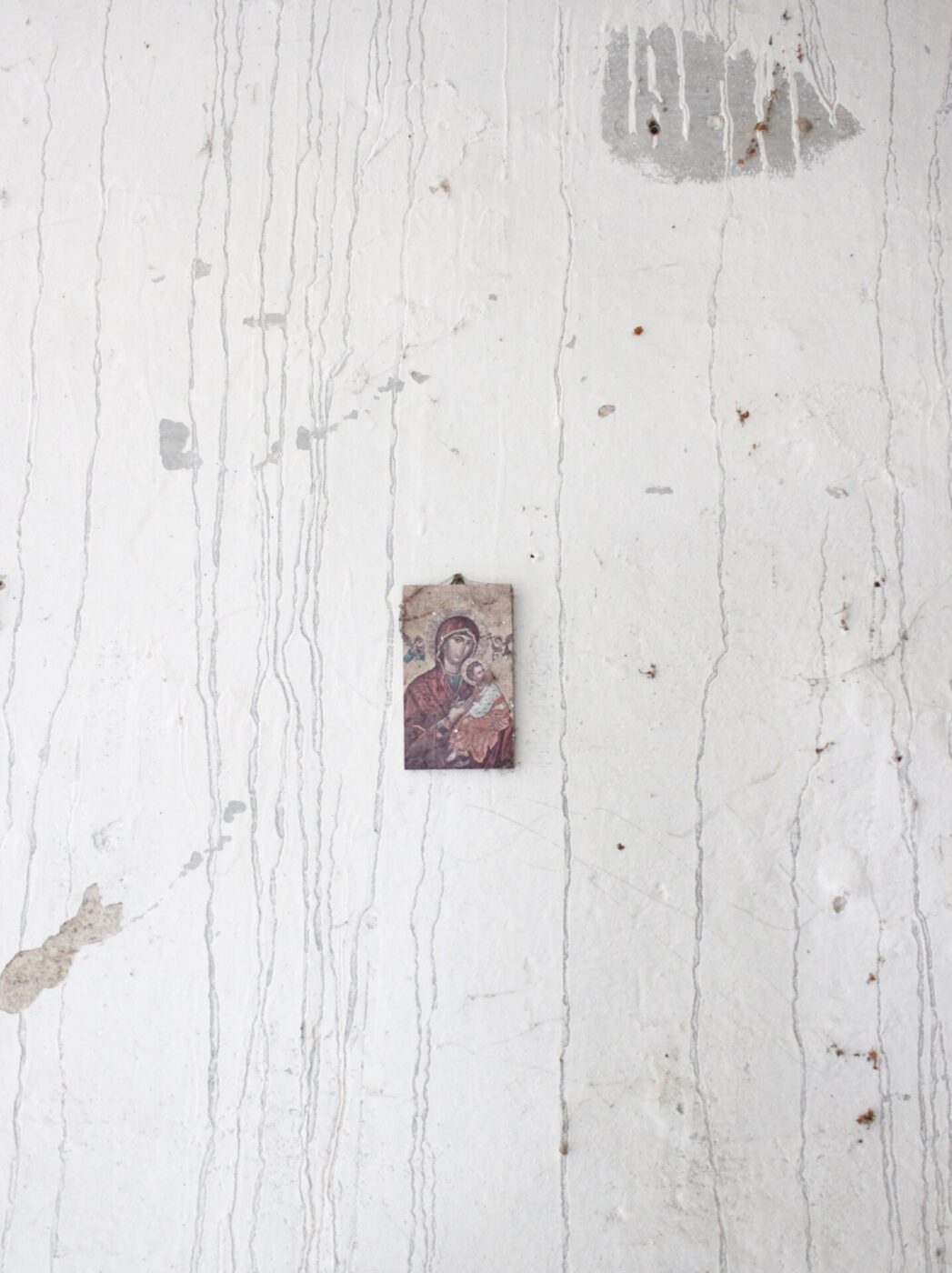

Madonnina statues are enshrined on street corners, watching over intersections from north to south. She adorns necklaces alongside crosses. Her image veiled oversees bars, gelaterias, and even butcher shops—a commercial patron saint. You see her plastered on walls throughout Italy, guides taking countless nonne e nonni to famous Marian shrines across Europe. You know you’re Italian when Lourdes, Fatima, and Medjugorje ring an immediate bell.

Weddings too remind you of La Madonna’s presence, thanks to “Ave Maria”, a favorite for walking down the aisle. And if the legion of women named Maria (Mary) do not testify to the prominence of La Madonna in Italian lives, then perhaps looking up and seeing her crowning churches as grand as Milano’s Duomo will serve as testament. A legend has it that angels transported Mary’s house from Nazareth to Loreto in Le Marche. Margherita may have been Queen of Italy, but it’s Maria–La Madonna–who is the real reigning royal here.

The Italian adoration of Madonna may baffle traditional Christians. How does Mary garner more reverence than her son, Jesus, the central figure of Christian worship? Jesus is undeniably significant, sure, but this is Italy, a realm where maternal influence is paramount. In this land, mothers and grandmothers hold immense sway over their children’s hearts here, and the concept of “mamma” is sacred (we didn’t get the nickname of “mammoni” for nothing). If mamma rules Italian homes, then the ultimate mother–Jesus’ own mother–rules supreme over Italian lives.

This allegiance transcends faith, and understanding the Italian devotion to La Madonna is an important piece of the Italian identity puzzle. Catholicism, even for those who are non-denominational, is a cornerstone of Italy’s cultural tapestry and, as such, Mary is deeply integrated into our lives, no matter our religious beliefs: staunch atheists exclaim “O Madonna!” and happily partake in Mary-associated celebrations. There are numerous feast days dedicated to her here–two of which are national holidays–and the south, especially, celebrates them wholeheartedly. Many believe that those like Naples’ Madonna dell’Arco feast and Avelino’s La Madonna di Montevergine procession for the LGBTQ+ and transgender community are a celebration of the Divine Mother’s unconditional love.

Yet the most important celebration of La Madonna is, without doubt, Ferragosto, the holiday that perhaps most defines Italian lifestyle and existence. The month-long holiday (which too has its origins in Roman pagan lore) kicks off on the 15th of August, commemorating the day when the Virgin Mary was reportedly taken body and soul to heaven. On the 15th, Italians follow in her footsteps and head to their own heaven: the seaside. And dedicating the liveliness of Ferragosto to Mary is no coincidence.

Ardor for La Madonna dates back to Roman times. Since then, Italians have consistently sought or worshiped figures akin to “mamma“–from Ceres, Goddess of Harvest, who mourns her daughter Persephone’s abduction by Hades to the Roman-adopted Egyptian Goddess Isis, who is often depicted as a mother figure nursing her baby Horus. It was also not uncommon for emperors to liken their wives or mothers to divinity, meriting worship even if human.

The first depiction of Mary herself showed up to the 2nd century, and today you can still see her in the Catacombs of Saint Priscilla in Rome, with Jesus in her arms. Upon Christianity’s ascendancy in Rome, devotion to Mary, not her child, surged, surpassing most other Catholic cultures. Pinnacle artworks bear testament to this, like Michelangelo’s evocative La Pietà, portraying Mary’s anguish as she holds her deceased son. Her biggest claim to fame, perhaps, is late medieval artist Giotto’s Ognissanti Madonna (1310); the work, a golden altarpiece depicting Mary surrounded by angels, is often credited with sparking the Renaissance. It’s now on display at Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, whose hallways are chock full of La Madonna–pay a visit if you want to get the full scope of Mary reverence.

Italian identity is so entwined with Mary that artists often depict her with Italian features, overlooking her Middle Eastern heritage. In the televised series Gesu di Nazaret (Jesus of Nazareth), director Franco Zeffirelli ensures the six-hour long series showcases Jesus’ Jewishness and Middle Eastern origins, but his very Italian reverence for La Madonna seeps through. When Mary holds Jesus after he’s taken down from the cross (a reference to La Pietà), Zeffirelli had the British-Argentinian actress playing Mary to cry out in Italian, “O figlio mio!” (“Oh, my son!”)… despite the entire script being in English.

It’s a concept referenced in American productions too. In Under the Tuscan Sun, protagonist Frances, an American who’s recently moved to Tuscany, begins to notice La Madonna everywhere, quickly realizing that La Madonna is everyone’s patron, everyone’s mamma. And there’s a reason why she uses “mamma” and not “mother”–the Italian meaning holds much more weight. For Jesus’s mamma–La Madonna–is Italy. And Italy will always be for La Madonna.