There is a village an hour west of Turin that is in part where I’m from.

It is settled amidst the rolling hills of Piedmont, that place of dark soil and burnished leaves, and without a car is difficult to reach. I get a bus that trundles unsteadily to the nearby town of Giaveno, and from there a taxi.

“Are you nervous?” Davide, the driver, enquires when we arrive. During the journey, he asked me politely what business a girl who speaks Italian with an English accent has going to a rural village, so far from the known boulevards of Turin. I told him: this was where my grandfather was born, before his family whisked him across the border in the 1930s to be brought up in France, where life was said to be a little easier, the work said to come more freely. He spoke of this village often, and of his cousin there, a man called Giorgio. I had never been, nor had I ever met my Italian family.

Davide enthused at the story of ancestral reconnection. “Una bella cosa, la famiglia” (“Family is a wonderful thing”), he said sagely, adjusting the wing mirror so he could gleam delight at the back seat. Now, it seems, he is as emotionally invested in the reunion as I am.

In the lead-up to this trip, I’d told my friends of my desire to meet my long-lost cousins. In part, because I find the term a comically romantic one, but largely because it was easier than referring to my grandfather’s cousin, and then having to explain why that tenuous connection is so important to me.

My grandfather, one of an estimated 30,000–40,000 Italian political refugees who fled the rise of Fascism, always wanted to take me here. His parents spoke French to him growing up, not Italian, as part of a broader determination to integrate. He was naturalized at 18, married a French woman, my grandmother, and had three French-speaking children; his name, Severino, was Gallicized to Severin. Yet he felt Italian, and perhaps for this reason, he wore the label of Coazze, the village that was his birthplace, as proudly as a brooch. Even decades of assimilation in France and an absence of language and documents could not negate the Italian-ness of that fact.

He passed away in spring, the season of soft, light transition, and we never got the chance to make the trip together. But I still had the stories he told me: his birth in a barn where the winter cold could not permeate; the aunts, uncles, and cousins, who, on early family trips back to the village, cried when they arrived and cried when they left. I am Italian, was his reverberating message through those oft-told tales, and that sentiment was contagious. Because of it, I had studied the language, lived in Rome. Still I had not been to this place where it began.

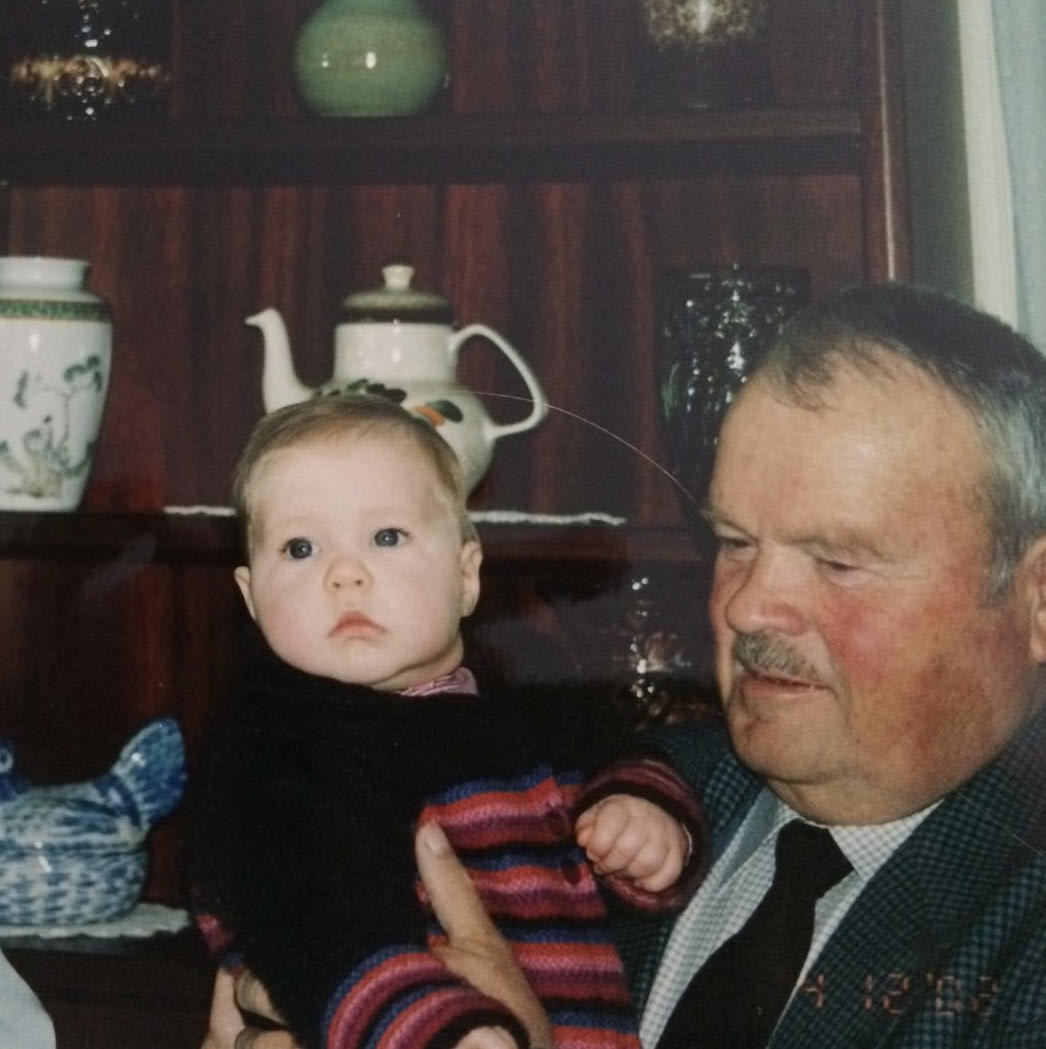

Author Clementine Lussiana and her grandfather

It is Autumn now, and the hills are stained amber. The season’s first mushrooms blink up at the sky. It’s cold, and the air smells of wet leaves.

I have never even seen a photo of Giorgio, but I know who he is when I see him because he has the same chortle and gait as my grandfather. I use the formal lei when I speak to him, and he tells me not to. We are family, he says, are we not? We are, I nod, switching to tu, and his eyes crinkle with pleasure the same way my grandfather’s did.

Family has become a sticky matter in Italy of late. A new law was passed in May of this year, restricting Italian citizenship by descent. While previously, anyone with an Italian ancestor who lived after March 17th, 1861 (when Italy was unified into a single kingdom) qualified to be a citizen under the descendant bloodline law, now recognition is limited to two generations. Applicants for an Italian passport must have at least one parent or grandparent who was a citizen by birth, and exclusively held Italian citizenship at the time of death.

Brought about in the name of bureaucratic efficiency, the new law opens up all kinds of questions around whether one’s connection to a country is something that can or should be quantified. The government cited the desire to “enhance” the link between Italy and the citizens abroad, a notion that threatens to delegitimatize the italianità that is so central to proud Italian diasporas across the globe. Nicola Carè, politician and member of parliament for Italy’s Democratic Party, has spoken to the emotional impact of the amendment, saying that “identity cannot be erased,” and “those with Italian blood cannot be denied the right to feel part of the Republic.”

Carè’s words are important. They reflect the idea of heritage as something deeper, more bodily, than the presence of generational citizenship. When homecoming is an act that is, at its heart, primal (I’m thinking of turtles, salmon, migratory birds), and often accompanied with the nebulous idea of Belonging, it feels unnatural to attempt to wrestle it into a bureaucratic box.

Perhaps because of my own background, I have become interested in second- and third-generation Italians who, raised abroad, have decided to move to Italy. I speak to Camilla, whose parents are Italian, but who was born in Norway and raised in Texas. She tells me how her family would return to Italy every summer, and about the pull she would feel to the country when she was back in the US. This sensation, to her so serious, was one her mother found deeply amusing.

“You know Italy as Sardinia in the summer,” she would say. “Of course you miss it.”

Clementine's family in Piedmont

Even so, Camilla describes the feeling manifesting itself as a nagging thought that would not go away. She spent an Erasmus in Florence in an attempt to scratch the itch, but the pull only became greater. Despite the job scarcity causing young Italians to leave Italy (the youth unemployment rate in Italy is as high as 21%), Camilla felt the only option after graduating was to move back, this time properly. She found a job as a student services assistant and settled into Italian life. “If I hadn’t moved to Italy, I would have always doubted myself,” she tells me.

Mauro, a second-generation Italian whose parents came to London as economic migrants, decided to return to Italy a year ago. I ask him to describe that tug toward an ancestral homeland, and he tells me about his parents’ dream of returning to Italy; a hope that fostered a nascent curiosity in him, then took hold once his children finished school and he saw a realistic window to leave the UK.

“I wanted to see what this other life was,” he says. “The one my parents used to have.”

He toured around Italy on a motorbike for three months before settling on Milan; close enough to his father’s Padova and the Northern Italian lifestyle he had become attached to, big and busy enough to be a natural transition from London.

“I just wanted to scratch the itch,” he reflects, when I ask him what finally clinched his decision to move.

It interests me that both Camilla and Mauro describe their desire to return to Italy in such bodily terms: a pull, an itch, a thought that will not stop nagging in the head. In a socio-economic context where many Italians are choosing to leave Italy (from 2023 to 2024, 270,000 Italian citizens emigrated, up around 40% from the two years prior), citing the country’s stagnant economy and low wages, those choosing to return are going against the grain; perhaps reaping the rewards of their ancestors’ own departure to countries where the jobs were more plentiful. In light of the Italian government’s recent decision to restrict who qualifies for “official” Italian-ness, this kind of urge for a transgenerational homecoming speaks to the complexity of what it means to belong, the difficulty in pinpointing a physical feeling of attachment to a place where you did not grow up.

Severin and his two aunts

My own pull to that village in the hills of Piedmont has now led to lunch with Giorgio and his wife Maria-Teresa—for what is an Italian family reunion without a meal? Through a jumbled mix of Italian and dialect, my grandfather is breathed back to life. We exchange stories yet unheard, and I marvel that I can meet new parts of him, even though he is now gone. They take me to their home and show me that famed barn of his birth, now a kitchen. This is a homecoming in the truest sense of the word, one where footsteps have been repeated across generations. It is, I am sure, psychosomatic, or perhaps a symptom of Giorgio and Maria-Teresa’s warmth that I feel such a belonging to this little village I do not know; but a small romantic voice within me whispers big words like ancestry, and I like to let myself listen to it.

By the time I leave the village, the sky is softening under the weight of evening. The dim light makes everything hazy, the pink walls of the church, the stone bodies of the hills. I say goodbye to Giorgio and Maria-Teresa, those cousins no longer long-lost who have shown me something of where I am from. Come back, they say, and I tell them I will.