If Florence’s Sant’Ambrogio neighborhood were a house, Cibrèo Caffè would be the living room. One of few places in the city that will welcome you at all hours of the day (or at least 9 AM to midnight), every day of the week, Cibrèo Caffè is in the heart of the area, between the Mercato di Sant’Ambrogio and Cibrèo’s three other restaurants on Via dei Macci and Via Andrea del Verrocchio.

It’s no coincidence that this feels like one of the most purely Florentine nooks of the city center. When Fabio Picchi opened the original Cibrèo Ristorante in 1979, Sant’Ambrogio was a “forgotten” area of the city, his son Giulio says. Fabio, whose absence has been deeply felt in the city since he died in early 2022, was one of the first entrepreneurs to implement his ideas in the neighborhood. It worked—four decades later, Sant’Ambrogio is probably the most thriving example of how Florence’s tourism and local customs can coexist, and Cibrèo is still renowned for being both forward-thinking and rooted in tradition.

Giulio, now the co-owner and “host” of the Cibrèo Group, has the task of maintaining this balance. “This is the real challenge for me: how I can continue on with something new but stay true to our identity, because I don’t want to destroy what my father did here in Sant’Ambrogio.”

It’s just before 9 AM on a recent Saturday, and Giulio is fueling up on scrambled eggs with stracchino–the royal family of Qatar is supposed to come by the Caffè this afternoon.

9:00

“Florentines love kidneys; they’re like the guy in The Silence of the Lambs,” says line cook Jun. He’s slicing away at veal’s rognoncini (kidneys), which he’ll pan-fry to order with sage and garlic. He got to the kitchen an hour ago, and though breakfast isn’t the busiest time of day for the cooks, they take any moment when there are no orders to finish their prep.

Jun, from South Korea, is joined by Samir from Syria, who has worked his way up from stage to chef over the last six years. He’ll spend most of the day expediting orders, finishing plates, and passing them to servers through the window between the kitchen and bar. “I love the adrenaline,” Samir said, frying three pans of eggs at once. “In a service when we serve 100 people and don’t make a mistake, I’m tired, but I’m satisfied.”

10:04

The clattering of coffee cups and whizzing of the milk frother competes with the steady hum of chatter and foot traffic outside, as people go about their Saturday morning market hauls and meetups with friends. Plates of “mi voglio bene” (“I love myself,” or fried eggs over toast with Parmigiano) fly out of the kitchen. On the patio, a pair of 70-something Italian women show each other the books they’ve been reading, and a tourist couple preps for a day of sightseeing with spritzes.

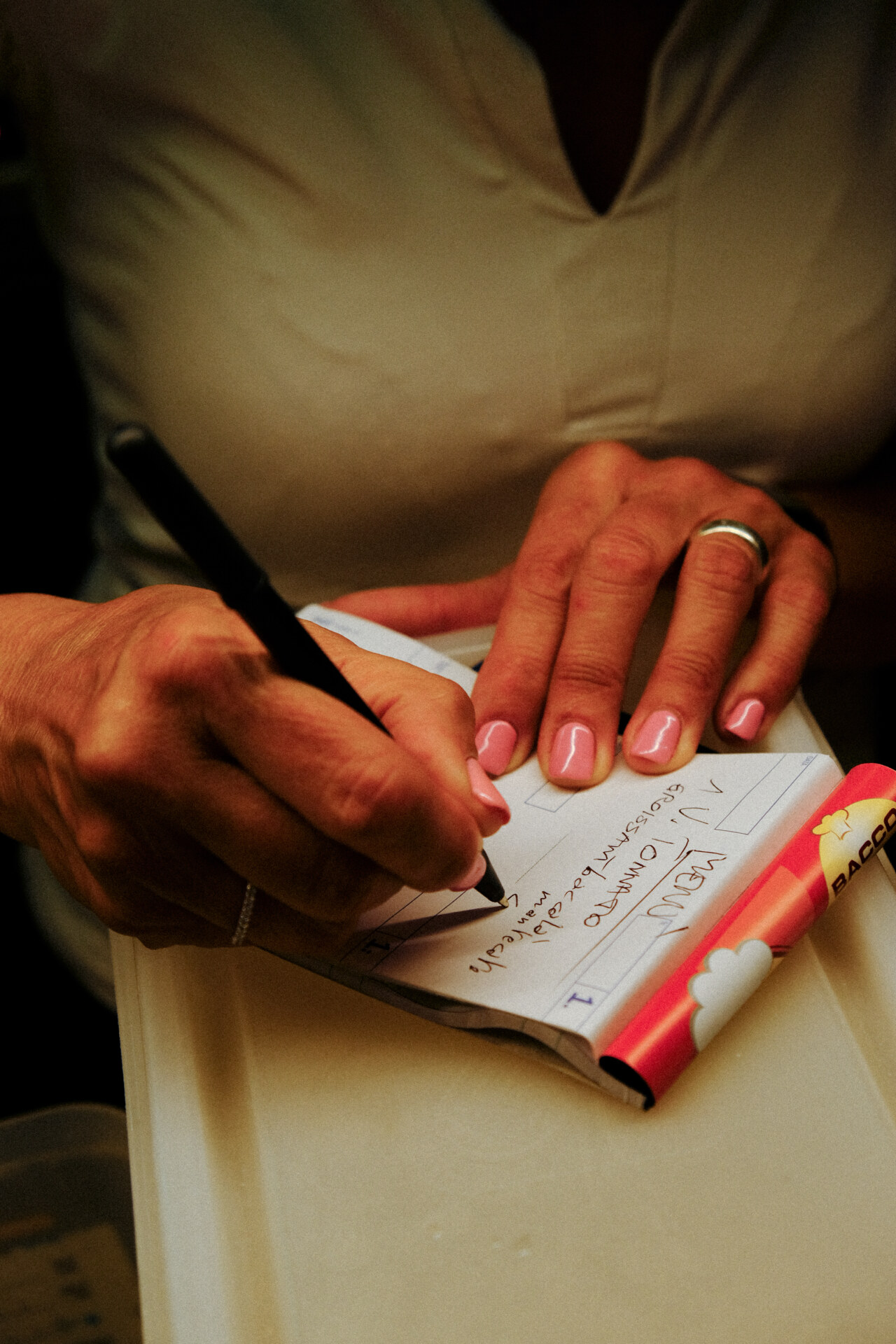

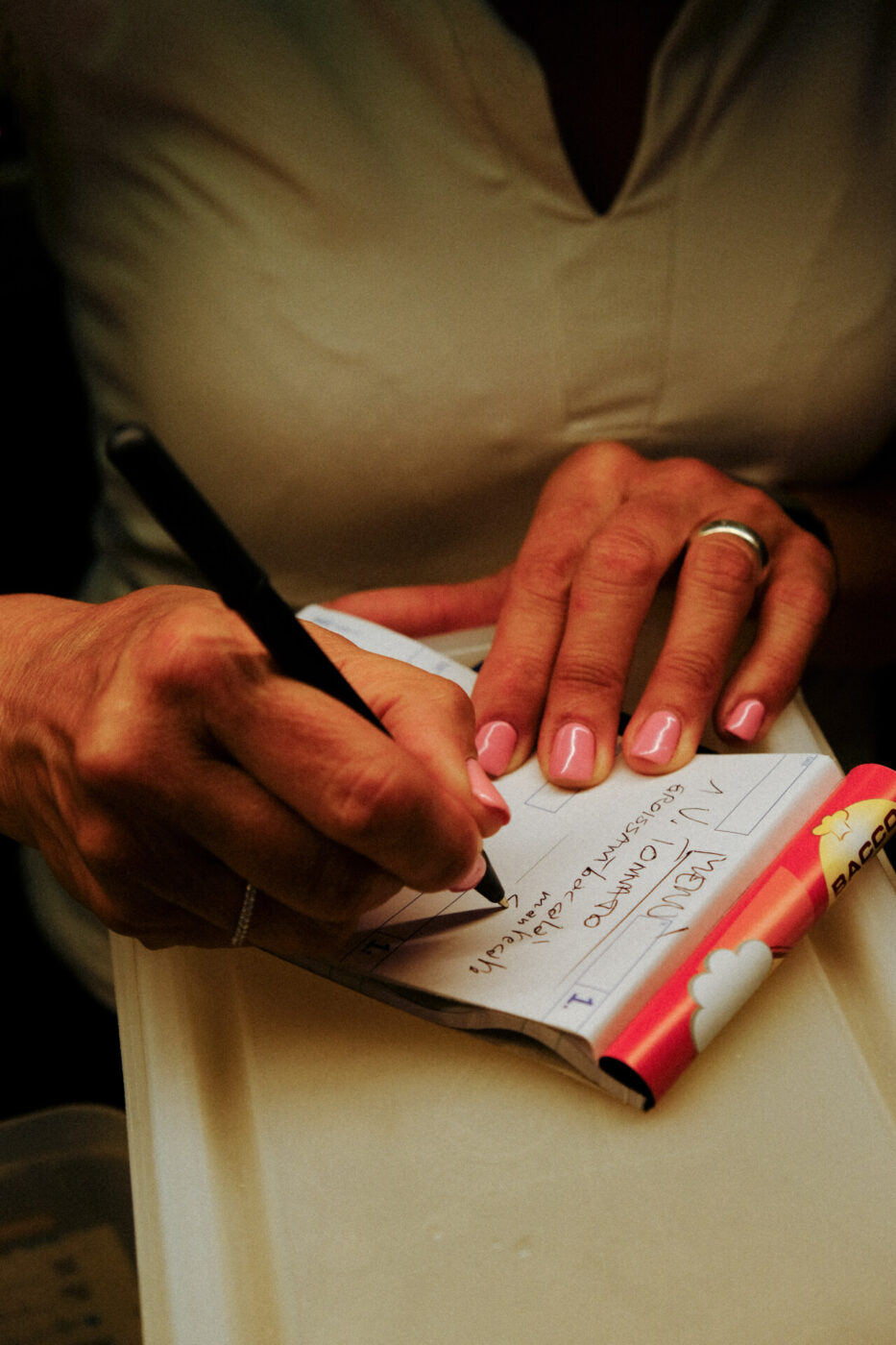

Front-of-house staffers Zarah, Annalisa, and Rilinda scurry back and forth between the bar and tables with glasses of red wine, iced tomato juice, and endless cappuccini. As soon as one tray of drinks is whisked away, Yumiko, the Japanese native who has headed the bar for more than 20 years, sets down another round of coffees. Zarah, from the Philippines; Annalisa, Florentine; and Rilinda, from Albania, won’t stop moving for the next five hours. This has been Rilinda’s routine for the last 23 years. “È la famiglia” (“It’s family”), she answers when asked why she’s stuck around for so long.

11:21

James Bradburne, “il fedelissimo”, is here. He’s going on year 17 as Cibrèo’s “most loyal” customer—or maybe believer is a better word. Though the former Palazzo Strozzi Foundation director now works for the Pinacoteca museum in Milan, he spends enough weekend mornings at the Caffè that his colleagues once gifted him a picture book of all the photos he’d texted them of his Cibrèo breakfast: always a cappuccino and cornetto salato, enjoyed at his left-corner table.

As much as he loves his breakfast ritual, James doesn’t come to Cibrèo for the coffee. A longtime friend of Fabio’s, James sees the Caffè as “a profoundly political place,” where strictly seasonal food is served to and by people of all ages, faiths, and backgrounds. And though Fabio’s famous “rules”—about the freedom of expression, importance of listening, and value of sharing space with others—were posted outside of Teatro del Sale for members of the cultural association, James believes they apply at all Cibrèo outposts. “Everything Fabio did was an expression of how he believed the world should be,” James said. “I come here because I still believe in that vision.”

12:03

The kitchen smells like pomarola, which everyone seems to be ordering during the lunch rush. Samir simmered the fiery-orange tomato sauce all morning, blended it with a heap of Parmigiano, and is now serving it with twirly busiate. Jun has all six stove burners blazing at once—some for the seared chicken going on salads, and most for pasta. Orbs of cacio burro sauce (a cheese and butter revelation that’s far more velvety, yellow, and deeply flavored than you’d expect, thanks to a touch of blended carrot) melt in sloped pans and coat strands of tagliolini.

“Smaller kitchens are comfier kitchens,” Giulio says, grabbing a bottle of water from the fridge while three cooks and one dishwasher crowd the rest of the room. At 30 square meters, this kitchen is by far the Cibrèo Group’s smallest, but maybe he’s right that they’re more practical: no one has to shout to make themselves heard, and Jun can reach the stove, broiler, and counter without taking more than one step. (And no one’s sleeves have caught on fire.)

13:30

There’s not a free table in sight. Sitting on the red velvet, cinema-style chairs, an older man reads La Repubblica, a German couple shares buttery seared liver, and an Italian couple chats while their son plays his Nintendo Switch, then dutifully puts it away when his pasta al pesto arrives. In the back corner, a woman lets her tiny terrier, wearing a pink bow, lick dollops of pastry cream off her fingers. Zarah, who has worked here for seven years, drops off plate after plate of Cibrèo’s smooth almond dip, scordiglià. The complimentary condiment comes with salted sourdough bread, a perk that surprises and delights anyone accustomed to saltless Tuscan bread. “Doing this job for a long time, you know what people want before they open their mouth,” Giulio says.

15:07

As the mom wipes pesto off her son’s face and the last lunch guests trickle away to continue their Saturday, Rilinda finally has a chance to eat staff meal: cavatelli with tuna, tomato sauce, oregano, and mint. Yumi gets a break from making coffees, pouring Prosecco for a woman who, having just come from the market, rests her bag of tomatoes on the floor.

16:00

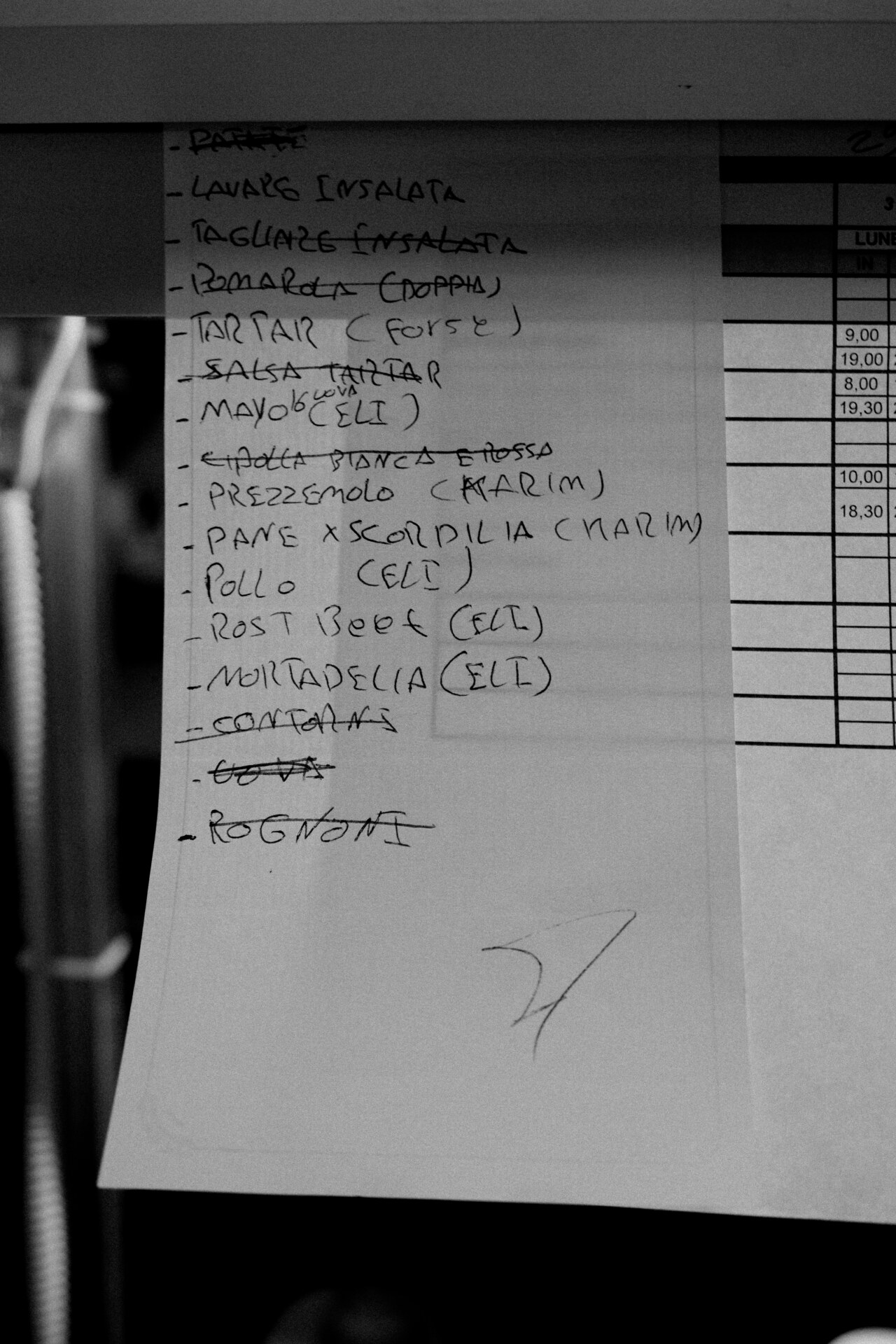

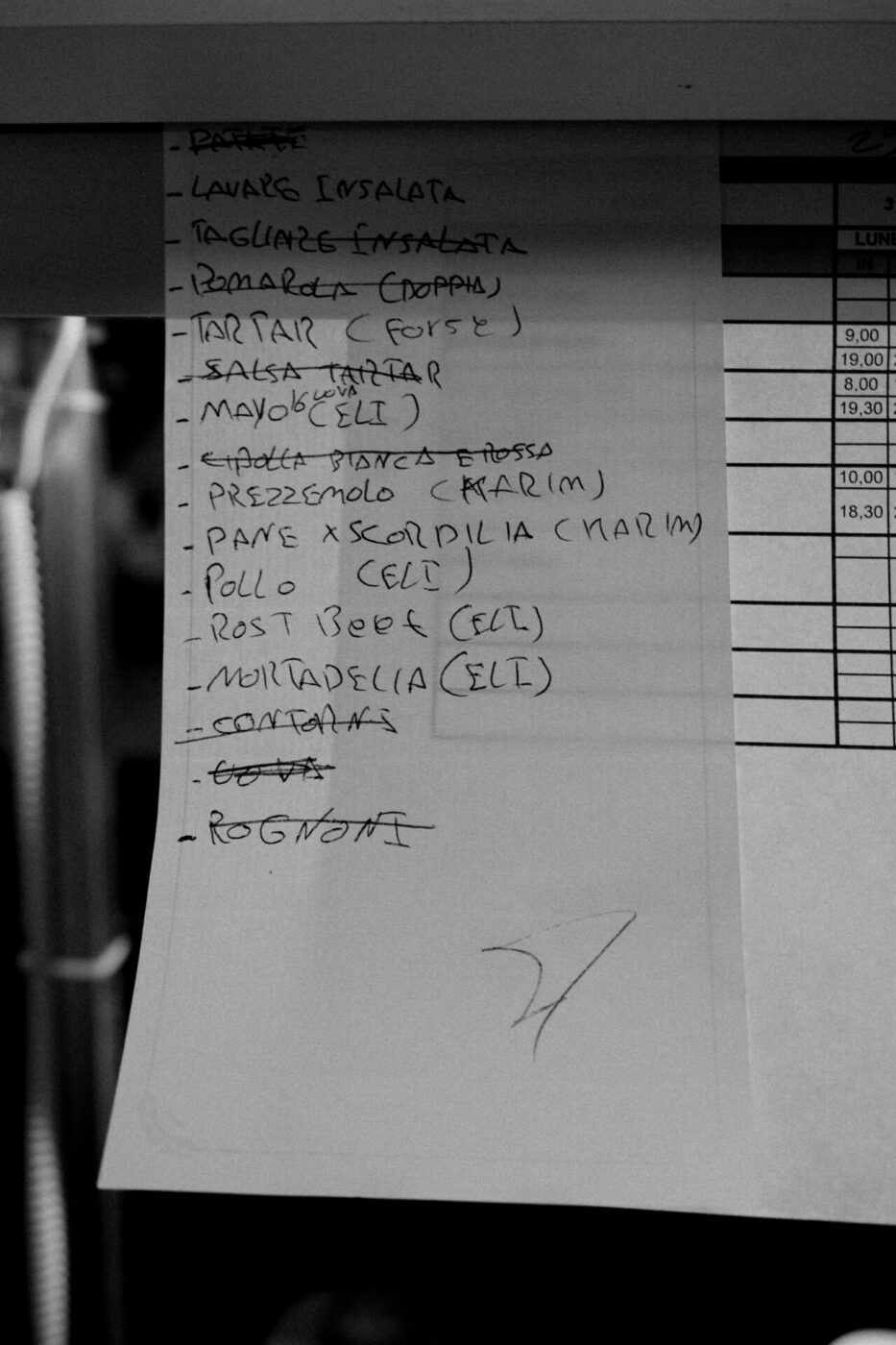

Samir and Jun have gone home for a rest, but quick chopping sounds come from the kitchen. Elijah, who’s been a line cook at the Caffè for the last six years, is teaching new trainee Abdul how to make mayonnaise and finely mince beef tartare, among other things on their long to-do list before the dinner service.

“I like it when it’s brown and becomes a little bit crunchy, and the inside is soft and juicy,” Elijah says admiringly, flipping roast beef over in a skillet. He bathes it in a cumin, turmeric, and lime butter sauce while the inside is still rare.

Abdul hurries to the Ristorante kitchen to drop off antipasti and vacuum seal bags of mortadella, while the Ristorante’s chef comes to the Caffè to put seafood soppressata in the fridge. Cibrèo’s cooks call this the “symbiosis” among the five Sant’Ambrogio kitchens: the Ristorante makes side dishes for the Caffè, Teatro del Sale’s cooks make vegetable dishes for both, and organic grocer C.Bio handles the bread and desserts for everyone.

17:27

“Being here is like being in another house,” says Gabriel, a 21-year-old from San Casciano who works as a waiter in the evenings. Like a Sant’Ambrogio time capsule, Cibrèo Caffè is a puzzle made of different pieces of the neighborhood. The wood for the bar and kitchen entryway were sourced from an old nearby pharmacy and courthouse. Lampshades and serving trays come from Lisa Corti’s Home Textile Emporium next door, and Giulio’s artwork is all over the walls.

Sant’Ambrogio’s many characters seem to treat the Caffè like a home, which is quiet now. The chef of Ciblèo (the group’s Tuscan-Asian fusion spot), now in Birkenstocks and a T-shirt, stops by the bar for a coffee. Helene, a banker who lives upstairs, sits down for her daily aperitivo. Her three-year-old French bulldogs, twins named Thelma and Louise and Cibrèo’s “mascots”, guard the door.

19:00

Customers, more of them now, are leisurely drinking negronis and eating olives on the patio. Elijah pipes out portions of mashed potatoes to stay warm for the dinner service. Jun is back, making salsa verde for anchovies.

20:36 – Close

This is the time of night that Caffè staffers call “dancing.” The servers waltz in a triangular path from the bar to pick up plates of chicken liver mousse and steak haché, to the dining area to drop them off, and to the kitchen to throw dirty tablecloths in the bin, take a deep breath, and repeat. The cooks move about their small space dexterously, plating one hot pan of pork neck while putting another cold pan in its place. Jun sings “Take Me Home, Country Roads” while slicing roast beef.

When one group gets up, another is ushered in. The customer mix seems to be about 50/50 locals and foreigners. A young, tattooed Italian couple hugs aggressively by the doorway. Americans in floral dresses excitedly take pictures of their tortelloni.

“We are trasversale, not exclusive,” Giulio says about Cibrèo. The group still operates under Fabio’s belief that wherever people come from, they want the same basic things in life, especially at the table.

If that egalitarian spirit goes, James mused earlier, “Cibrèo will just be another café that will compete with other cafés. If it stays, it’s not competing with anybody, because there’s nothing else like it.”

***

If you’ve made it this far, here’s a secret for you: Go to Cibrèo often enough to make friends with Giulio, and you’ll be the lucky recipient of a dessert the pastry chefs only make on occasion—a life-changing cheesecake with red wine poached pears.