In mid-century Italy, going to the cinema was the thing to do. The release of a new Totò film, the most recent Fellini, or Sergio Leone’s latest western were unmissable events. The next day’s water cooler chatter, newspaper headlines, and dinnertime gossip would revolve around new releases and their lingo, and to not be up to date was a special form of social faux-pas. Thanks to the cost of cinema tickets being much more negligible than today, it was one of few truly democratic social activities that most anyone could participate in.

There is a scene in Pietro Germi’s Divorzio All’Italiana (1961) which well documents the Italian ferment (just a year earlier) for the release of La Dolce Vita (1960) by Federico Fellini. In Germi’s movie, a reporter announces the arrival of a sensational new film, already preceded by scandals, controversies, and protests. Even the parish priest of the village warns his congregants not to go to the theater, so as not to support this morally corrupt work: his sermon achieves a very limited effect. Faithful and not, young and old, people flock to see the masterpiece. They bring their chairs with them, as the cinema does not have enough to accommodate everyone. Some people even come from the surrounding neighborhoods to attend the show, and to see Anita Ekberg sinuously move in the Fontana di Trevi.

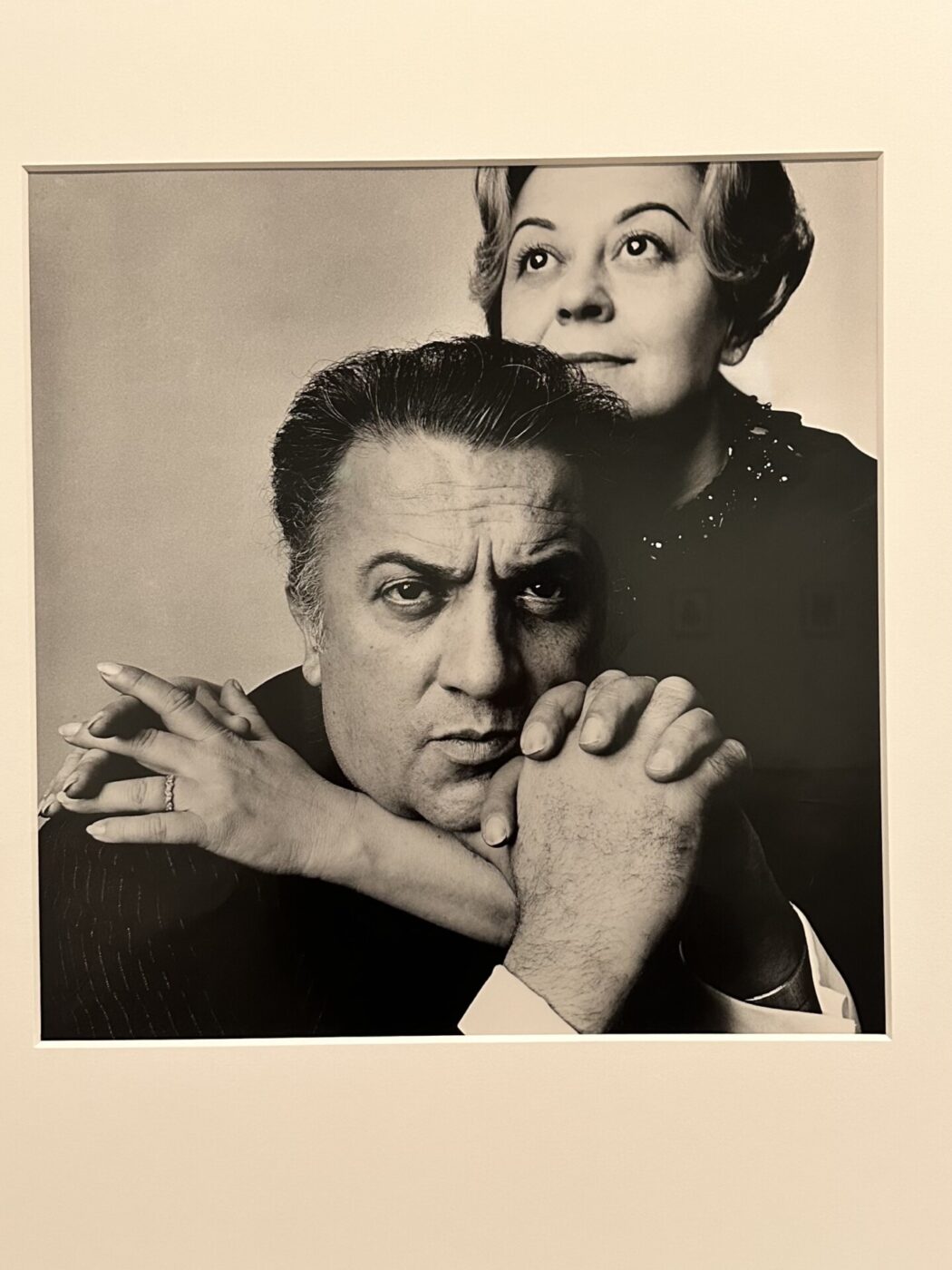

The mass enthusiasm for the spicy film helped Fellini become the inarguable golden star of Italian cinema. He, in turn, elevated Italy’s status on the global cultural stage, and, as such, his influence extended far beyond cinema–so much so that an adjective was created to describe his style, Felliniesque. Italian art, literature, and fashion took from his distinctive style, and memorable characters even inspired words that are now used worldwide.

From the silver screen to our everyday conversations, these are three terms that you may not have known came from Fellini’s oeuvre:

PAPARAZZO

“Enterprising and unscrupulous photographer, who goes to hunt well-known personalities to shoot them by surprise, especially in particular moments of their private life, typically for tabloids.” –Treccani

The term paparazzo was born with La Dolce Vita, and was the name of a character played by Walter Santesso. In the film, Paparazzo embodies the pursuit of celebrity and sensation that defines the glamorous, yet morally ambiguous world of post-war Rome. As a relentless and opportunistic photographer, Paparazzo’s character serves as a representation of the pervasive intrusion of the media into the private lives of public figures, always seen buzzing around, camera in hand, waiting to get the scoop.

But where exactly the name comes from is still uncertain. Ennio Flaiano, co-screenwriter of the film, claimed that the term had been taken from the surname of Coriolano Paparazzo, a Calabrian hotelier featured in the early 20th century book Sulle Rive Dello Jonio by George Gissing, which came into the hands of Fellini by chance. There are those who argue, however, that Flaiano was inspired by the Abruzzo dialect of his childhood, in which clams are called paparazze. In Flaiano’s mind, there was an association between the opening and closing of the photographic lens and the same operation of the clams. These are the two most accredited versions, but it seems that Fellini also associated, from a phonetic point of view, the word paparazzo with the term pappataci (sand flies), very annoying small insects that plague Italian summers. Giulietta Masina, wife and muse of the famous director, credited this version by attributing the coining of paparazzo to the union of the words pappataci and ragazzo (boy).

As for the inspiration of the character, it is certain that Fellini drew on the famous photographer Tazio Secchiaroli, known for having immortalized, some time before the making of the film, dancer Aichè Nana’s now infamous striptease at the “Rugantino” restaurant in Rome. The director had been so fascinated by this figure that he wanted to leave a trace of him in his film.

The word paparazzo caught on quickly, and traversed international borders. As early as 1961, it entered the English language, appearing in Time Magazine in an article titled “Paparazzi on the prowl.” Equally, other non-neo-Latin languages such as Japanese and Korean readily adopted the term. And this is how, starting from a character in a Fellini movie, the word has taken on a life of its own as an American thriller produced by Mel Gibson, a Filipino talk show, and a very popular Lady Gaga song.

DOLCEVITA

“Snug-fitting turtleneck sweater” –Treccani

That final scene of La Dolce Vita is so iconic that, in Italian, turtlenecks are called dolcevita–even though there was in fact no turtleneck present in said scene, merely the suggestion of one.

At the end of the movie, Marcello Mastroianni wears a black shirt with a dark scarf on the windswept beach, giving the impression, from a distance, that he is wearing a turtleneck. And the rest is history. (To cement his signature style even further, at the time of the promotion of the film, Mastroianni would often wear a turtleneck.) According to another current of thought, however, the word was born with the style of the character Pierone, played by Giò Stajano, the first openly transgender public figure in Italy, as well as the probable inspiration for Anita Ekberg’s epic bath in the Fontana di Trevi. Regardless, we can thank Fellini for giving our favorite cold-weather garment plenty of screentime.

It seems that the first print appearance of the dolcevita used as such dates back to December, 1969 in the Italian newspaper La Stampa: “About twenty venues are considered among the most beautiful in Italy, and the traditionalist ones still forbid entry to those who come wearing a dolcevita, without a tie or with a leather jacket.”

If the origin of the name dolcevita is not unequivocal, the origin of the garment is equally unclear. Some historians trace the birth of the sweater back to the Middle Ages, due to its ability to protect knights’ necks from contact with irritating armor. The Victorian-age ruff–those ornate frilly collars beloved by noblewomen like queen Elizabeth I– are also potential forerunners of today’s turtlenecks.

And be careful not to confuse lupetto with dolcevita: the former is distinguished from the latter, as the collar does not fold back on itself! This is still a typical Italian mistake.

Rimini

AMARCORD

“From the Romagna dialect: properly «I remember» – Memory, nostalgic recollection of the past” –Treccani

Finally, the word amarcord entered the Italian vocabulary after the release of Fellini’s movie of the same name, in 1973. Amarcord, the film, is a fresco of Rimini at the time of Fellini and co-screenwriter Tonino Guerra’s childhood; the latter came from the impoverished district of Sant’Arcangelo. As suggested by Guerra’s poem “A m’arcord” (see below), this new term brings together three words: A m’arcord–Io mi ricordo–I remember.

A m’arcord

Al so, al so, al so,

Che un om a zinquent’ann

L’ha sempra al méni puloidi

E me a li lév do, trez volti e dé

Ma l’è sultént s’a m vaid al méni sporchi

Che me a m’arcord

Ad quand ch’a s’era burdéll.

I remember

I know, I know, I know,

That a man at fifty

Has always clean hands

And I wash them two, three times a day.

But that’s only if I see my hands dirty

That I remember

When I was a boy.

Fellini was very undecided about a suitable title for his film, considering Viva l’Italia and Il Borgo, before having what he refers to as “a flash of inspiration” while sitting at a restaurant and scribbling on a napkin. The word amarcord is now used to evoke something that goes beyond a painful and personal vein of nostalgia, that embraces a more intimate, tender, and even accommodating memory of the past. Potentially, an amarcord is also a snapshot of an entire historical period, linked to the customs and traditions of a generation, rather than limited to a mere personal evocation. For Fellini, amarcord was “a bizarre little word, a carillon, a phonetic somersault, a cabalistic sound and the brand of an aperitif, too, why not? Anything but the irritating association with ‘je me souviens’. [‘I remember’ in French].” In Italian, it has become the sonorous reverberation of a feeling. It is a neologism, able to best express the impalpability of an elusive sensation, yet concrete in everyone’s mind. Every amarcord must therefore pay homage, in the words of Fellini himself, to “a past to be preserved as the clearest notion of ourselves, of our history, a past to be assimilated in order to live more aware of the present.”