Let’s say, for a moment, that life is a song. When we’re in the middle of it, it seems like it’s going to last forever. So too, those seemingly immortal figures who defined entire generations with their voice, vision, and creative expression.

It’s never easy saying a final “Ciao” to those iconic (for once, the word seems warranted here) identities from art, culture, cinema, and society who feel like they have been part of our lives for longer than we can remember. But 2025 was another story. Rosita Missoni, Oliviero Toscani, Pippo Baudo, Mirella Petteni, Arnaldo Pomodoro, Gianni Berengo Gardin, Claudia Cardinale, Enzo Staiola, Giorgio Armani, and Ornella Vanoni, among others. We said farewell to a constellation of Italy’s brightest and most beloved this year.

While they are no longer with us, their legacy endures, and reaches well beyond Italy. The following reflections from colleagues, collaborators, close friends, and admirers remind us that, beyond their international fame and public image, they were humans who lived by example, staying true to their values in both life and work.

A bronze sphere created in 1998 by sculptor Arnaldo Pomodoro; Photo by Paola Gospodnetich

ARNALDO POMODORO (1926-2025)

“The Master of Bronze”

You’ve most likely crossed paths with one of Arnaldo Pomodoro’s bronze Sfera con Sfera (Sphere Within Sphere) sculptures before. They tend to flash up in your life when you least expect them—perhaps while circumnavigating the Vatican Museums or crossing New York City’s United Nations Plaza. Considered cultural landmarks in cities across Europe, the United States, the Middle East, and Japan, they represent the pinnacle of Pomodoro’s sculptural work.

Arnaldo Pomodoro, the “master of bronze,” believed deeply in the manual and material value of his artistic work, embodying a fine balance between technical precision and artisanal creativity that became one of his hallmarks. “Disciplined” and “visionary” is how he is described by his peers at Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro—a man who “asked a lot of himself, and thus of others.” Carlotta Montebello, Executive Director of the foundation, worked with the Milan-based sculptor on the project’s inception in 1995 under his vision and direction. Since then, Montebello has been part of its evolution into a publicly accessible archive and collection dedicated to preserving and enhancing the legacy of Pomodoro’s work through exhibitions, awards, and global initiatives.

“He was not one to joke around; he took life very seriously,” she says. “He was strict, but at the same time very generous with all his collaborators. He wasn’t frivolous, but very sensitive. Pomodoro was a man you could count on, and he was a true supporter of younger artists. That is why his legacy endures through the Arnaldo Pomodoro Sculpture Prize, which he wanted as part of the Fondazione from the very beginning.”

Federico Giani, curator at Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro, reflects on the enduring relevance of Pomodoro’s work and the legacy of his sculptures far beyond Italy, particularly those in the public realm. Curiosity, Giani notes, is the greatest lesson we can learn from Pomodoro: a constant desire to discover and learn new things about himself and the world around him.

“In the most mature phase of his career, his visionary spirit was expressed in the creation of sculptures on an environmental, architectural, or landscape scale, some realized and others merely designed. For Pomodoro, each of these sculptures represented an invitation to the imagination, a threshold for embarking on a journey, and at the same time a window through which to look deeply into the complexity of our reality,” Giani says.

MIRELLA PETTENI (1939-2025)

“The Contessa”

“You needed to be Mirella to look like Mirella. It was never just about clothes,” says Milan-based art director and graphic designer Claudia Neri, who first met the model and society figure in the early ’90s through a work opportunity in Rome, and developed a friendship with her over the years. Although Petteni’s international modeling career had concluded by that stage, she was still, as Neri and others note, “a revered figure in the most coveted social circles”—a tastemaker who set the benchmark for style and decorum in every room she entered.

Photographer Gian Paolo Barbieri first shot Mirella Petteni in the early ’60s, instantly recognizing the allure of her modern, expressive look. With her long neck, high cheekbones, large eyes, and elongated physique, Petteni represented a departure from the conventional feminine beauty of the time, embodying the emerging modernist aesthetic that would define high fashion in the 1960s and ’70s. She went on to work internationally with some of the fashion industry’s most revered photographers, including Ugo Mulas, Irving Penn, and Helmut Newton, who shot her for multiple editorials and campaigns featured in Vogue U.S. and Vogue Italia.

“She had a style and attitude that were the epitome of modernity. She was light-years ahead of her time—possibly Italy’s first truly international model. She knew herself deeply and didn’t need anybody’s approval,” reflects Neri.

But Petteni was more than a model, more than a photographer’s muse, and more than the face of 1960s fashion. She was a presence—a woman who embodied “glam” without trying (and probably before the term even existed), wearing her refined, worldly demeanor as effortlessly as a silk Pucci kaftan. Little wonder Helmut Newton referred to her as “the Contessa.”

Mirella Petteni’s legacy endures in her determination, intellectual curiosity, and “intelligent brand of beauty,” which defined her as a bella figura par excellence across high society and cultural circles in Italy and New York following her retirement from modeling in her early thirties. Whether attending major art openings in Venice, spending weekends away in the Tuscan countryside, or hosting aristocratic gala dinners in Rome, Petteni surrounded herself with exuberant, creative individuals from the worlds of art, design, photography, politics, and journalism, supporting those who impressed her with their talent and sense of ambition.

“She was also extremely knowledgeable and generous when it came to her favorite interests—design, architecture, and art. I don’t think I’m revealing a secret when I say that in her later years she became quite a patron of the arts, helping struggling artists she believed in, often at very early stages of their careers. Time has shown she had remarkable instincts,” shares Neri.

Oliviero Toscani; Photo by Tom Mesic via flickr

OLIVIERO TOSCANI (1942-2025)

An “Explosive” Lens

You never forget the first time you see an Oliviero Toscani photograph. It hits you straight in the face. A Catholic priest and a nun locked in a passionate kiss; three human hearts lined up on a table; the blood-soaked clothes of a soldier killed in combat. Frontal, unambiguous, and stripped of ornamentation, his images are so radically direct in their questioning of the human condition that they provoke a mix of shock, intrigue, and often repulsion, all at once. Once you see one, you can’t unsee it.

While “explosive” is how Toscani’s lens has often been described by audiences, the shock value was never for its own sake. Toscani was the photographer and art director who, for decades, challenged us to confront aspects of culture, society, and life we often prefer to ignore: race, gender, aging, death, war, sexuality, corruption. Although he moved freely between reportage, portraiture, fashion, and advertising throughout his career, his lens was never focused on creating beauty. It was focused on provoking critical thought through the images we consume everyday.

Some of Toscani’s most controversial work was produced during his tenure as art director for the Italian fashion brand United Colors of Benetton, which began in 1982. His campaigns often featured photojournalistic imagery depicting subjects considered taboo at the time: an HIV/AIDS activist on his deathbed, a newborn still attached to its mother’s umbilical cord, and interracial and same-sex couples. Whether plastered on billboards in New York City or scattered through the pages of glossy European fashion magazines, Toscani’s campaigns sparked global outcry. Their moral clarity and urgency first made people uncomfortable—and then made them think. For Toscani, that was the whole point.

There have been exhibitions of Toscani’s photographs over the years, although parts of his works were censored or prohibited from being shown in major public institutions across Italy. His major retrospective at Palazzo Reale in 2022 titled Professione fotografo was therefore as much a collective cultural milestone as a personal one. Curated by contemporary art writer and commentator Nicolas Ballario, the exhibition marked a fundamental shift in public perception of Toscani’s work, affirming the enduring moral power of his images.

Upon the exhibition’s opening, Ballario wrote:

“This exhibition features 900 images hung like posters, as if the street had entered the building. No photographer in the world can boast such a varied and inclusive body of work, recounting the last sixty years of the human condition. But I would like to point out one thing: these posters were censored for forty years.”

“Until fifteen years ago, the mayor of Milan did not allow Toscani’s photos to be displayed in the city. Today, not only are they permitted, but celebrated in a symbolic location like Palazzo Reale. This means that, despite history, times have changed a little. Being optimistic today is a moral duty.”

From left to right: Roberto Carlos, Pippo Baudo, and Sergio Endrigo at the 1968 Sanremo Music Festival

PIPPO BAUDO (1936–2025)

Prime Time’s “Superpippo”

Every country has a beloved television personality who lit up prime time for longer than anyone can remember—the one who feels like part of the family, who makes the world feel like a better place whenever they appear on screen. For Italy, that was Pippo Baudo.

Giuseppe Raimondo Vittorio “Pippo” Baudo redefined the role of the television presenter over the course of his six-decade career. He hosted and directed 13 editions of the Sanremo Music Festival and served as a prolific talent scout on programs such as Settevoci and Fantastico. He launched—or at least, put a spotlight on—the careers of artists including Andrea Bocelli, Eros Ramazzotti, and Laura Pausini, and became artistic director and executive at RAI in 1994. These achievements represent only a fraction of Baudo’s cultural impact.

His crisp suit and tie was always accessorized by his best feature: that grin. When Pippo Baudo laughed, Italy laughed. When he spoke about culture, society, or politics, Italy joined in the conversation. Through his artistic vision and screen presence, he reminded audiences that television could be intelligent and curious as well as entertaining. His prime-time programs—including Secondo voi and Serata d’onore—featured writers, philosophers, and figures from the world of high culture alongside pop singers, comedians, and variety performers. The result was highly engaging viewing—if occasionally chaotic—and proof that mass media could still maintain cultural integrity. More than a television host, Baudo was a cultural mediator, a figure who understood television as a mirror of a changing Italy.

“As a kid, whenever there was a TV show hosted by Pippo Baudo, I knew it was going to be special,” recalls Beppe Savoni, music curator, producer, creative director, and founder of the Disco Bambino universe. “Seeing him on TV felt reassuring. It’s hard to put into words the massive impact he had—not only guiding Italian media from traditional codes toward innovative languages, but ushering an entire country into a new era of entertainment. Countless people in the industry owe their careers to him.”

Savoni met Baudo in person at age 11 during a local singing contest in Bari, which he later recounted in a tribute:

“In 1985, I had the chance to meet him. I was 11, taking part in a local singing contest that Pippo hosted. That night I also met Donatella Rettore—my childhood idol—who introduced me to him. He hugged me and said that Donatella’s music was a wonderful passion to have. My father took a photo, but he was so nervous that Pippo’s head ended up out of the frame. A moment I will never forget, just as I will never forget Pippo.”

Rosita Missoni with her husband

ROSITA MISSONI (1931-2025)

The Spirited Trailblazer

“The most important lesson I learned from Signora Rosita came through her example. She was a tireless worker, but above all a woman with an extraordinary ability to look ahead, guided by a constant orientation toward the future and an exceptional attention to detail. She combined great rigor with a lightness of spirit, approaching both work and life with clarity and grace,” reflects Missoni Creative Director Alberto Caliri.

Rosita Missoni was a trailblazer—a warm, revered force who dedicated her life to crafting a joyous, liberated expression of Italian style. She changed not just how Italians dressed, but how they thought about living well. Caliri, who has been part of the Missoni inner circle for more than 20 years, witnessed her intellectual curiosity and passion for both work and life firsthand. “In recent years, I shared with her an ongoing dialogue based on observation, listening, and exchange—discussing inspirations, fabrics, materials, volumes, and even installations for Design Week,” he says.

“We often had lunches at her home, a place immersed in art and color, where her creative thinking revealed itself in a spontaneous and vital way. In those moments, I understood how total her vision was—capable of naturally bringing together work, culture, and life.”

Signora Rosita’s legacy will endure as the pioneering woman from an artisanal textile family in northern Italy who co-founded the Missoni fashion house with her husband Ottavio Missoni in 1953. Under her vision, textiles, garments, and interiors were freed from the severity of perfection, favoring movement, texture, and spirit. From the house’s signature zigzag to its experimental knits, design became an extension of attitude and emotion rather than decoration—one that embraced “evolution, intellect, and emotional expression,” as Caliri notes.

Gianni Berengo Gardin; Photo courtesy of Carlo "Granchius" Bonini, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

GIANNI BERENGO GARDIN (1930–2025)

A Witness with a Leica

There is Italy, and there is Italy through the lens of Gianni Berengo Gardin. Gritty, rigorous, with a certain moral clarity, the photographer’s black-and-white reportage quietly reshaped Italy’s visual conscience in the postwar landscape. Gardin’s Leica captured the everyday lives, labors, and fragilities of a country in a state of transformation—a visual archive of Italy spanning industrial growth, urban evolution, family life, and marginalized communities. A morning commute on a crowded vaporetto in Venice (1960), a family lunch outdoors in Luzzara, Emilia-Romagna (1973), reflections of pensive passengers on a Rome–Milan train (1991): Gardin’s humanist gaze was rooted in both the small details and emotional lives of his subjects, as well as the social and cultural contexts of their surroundings.

Gardin therefore helped define photo reportage not as visual spectacle but as a moral testament to daily life in Italy. “I am not an artist. I am just a witness of what I see,” he would say. His “witnessing,” however, always seemed to carry a gentle commentary on Italian society, its people, and the human condition more generally—often highlighting stark contrasts between young and old, poverty and affluence, glamour and daily life, and tradition and modernity.

The photographer reminded us that looking “outward” also means looking “inward,” reinforcing photography’s role as a civic mirror and a prompt for collective self-reflection. While Gardin’s legacy endures in the scope and volume of his photographic books, commissions, and documentary work, the moral force of his images reminds us that witnessing is an act of responsibility—and that the most profound moments of truth and beauty reveal themselves when we pay humble attention to everyday life as it unfolds.

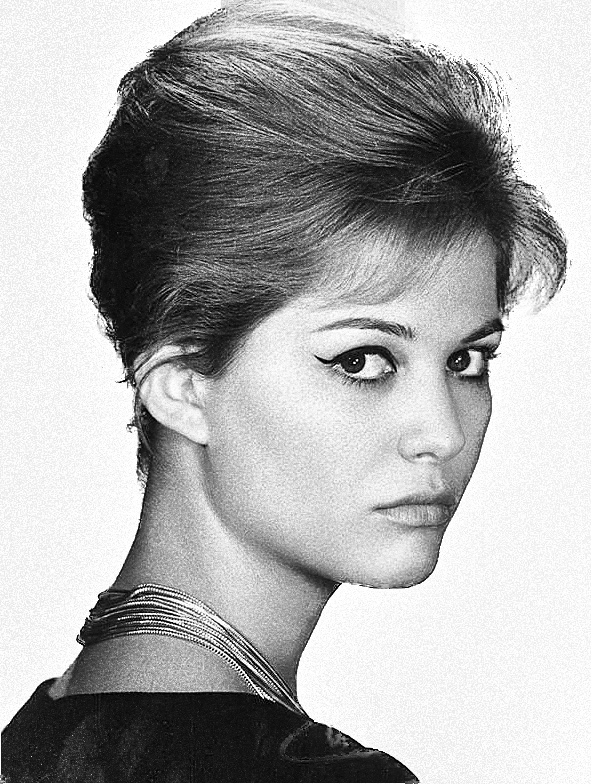

Claudia Cardinale, 1960

CLAUDIA CARDINALE (1938-2025)

“Italy’s Girlfriend”

Surely, modern femininity incarnate: the first appearance of Claudia Cardinale’s character in Federico Fellini’s Otto e mezzo (1963). The fitted white dress, the barefoot skip on tiptoe, the flood of sunlight that seems to radiate from her aura—and then, eccolo, the Cardinale smile. Part girl-next-door, part divine apparition, it is a smile that will endure in the Italian history books. That Cardinale is essentially embodying her own screen persona as “Claudia” reflects the fact that her presence—grounded, sensuous, relatable—was never merely a matter of performance. Fellini knew it. So did other directors like Visconti and Leone, who revelled in the psychological warmth she brought to the screen, even in more demanding or dramatic roles.

Often referred to by the press as “Italy’s Girlfriend,” Claudia Cardinale symbolized a new face of cinematic modernity and, in doing so, created a new archetype of European femininity. She was presence over polish, depth over artifice, and she influenced generations of women across Italy and France to understand elegance as nothing more—and nothing less—than being comfortable in one’s own skin. Surely, a valid reason to smile.

Moving effortlessly between Italian and international productions, Cardinale appeared in nearly 100 films over a career spanning the 1950s to the 2000s. She was a muse to some of cinema’s greatest directors and a reference point for designers and photographers alike. Yet a defining element of her legacy was her unwavering self-assurance. “I never felt scandal or confession were necessary to be an actress. I’ve never revealed myself or even my body in films. Mystery is very important,” she once said.

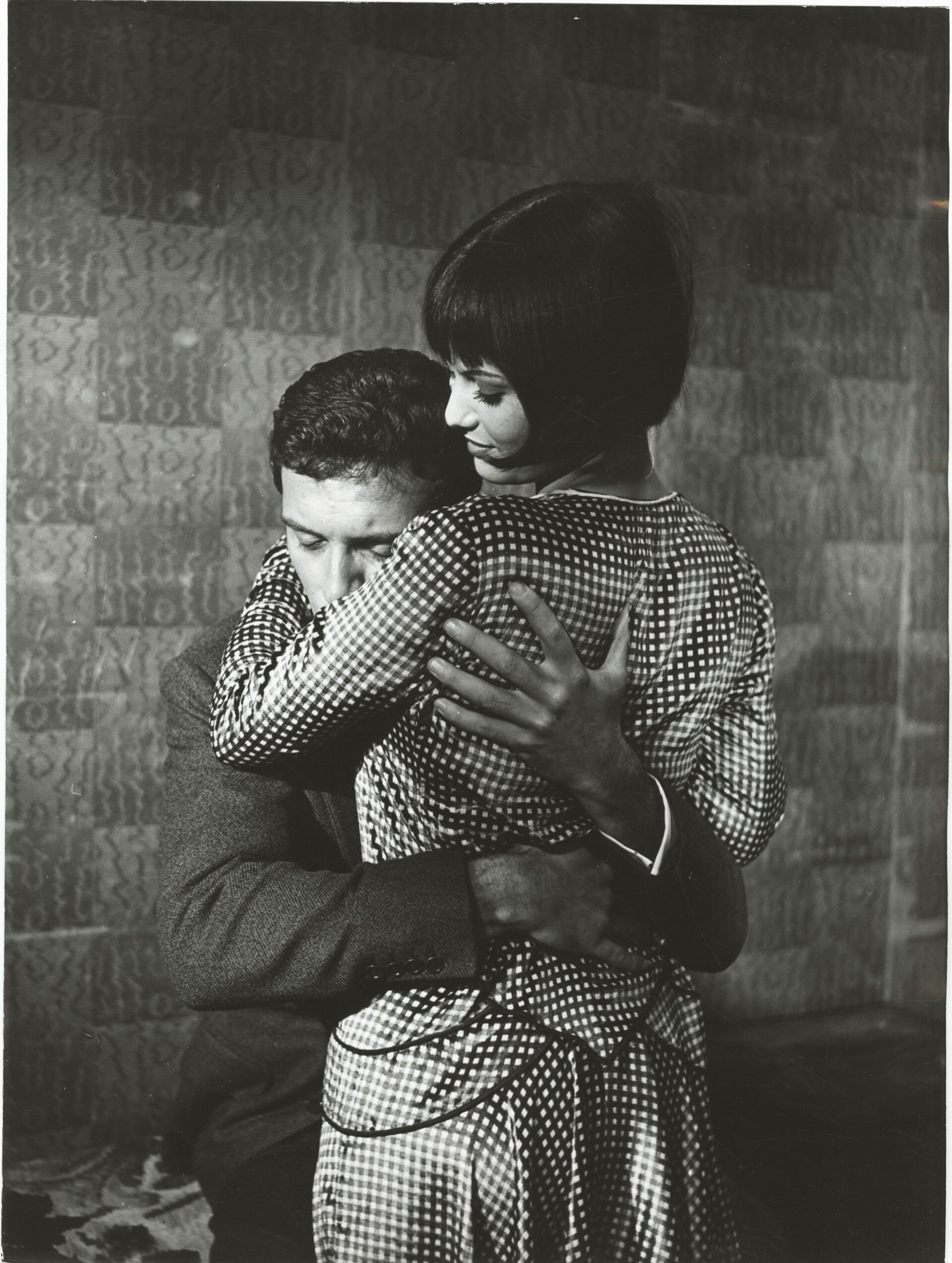

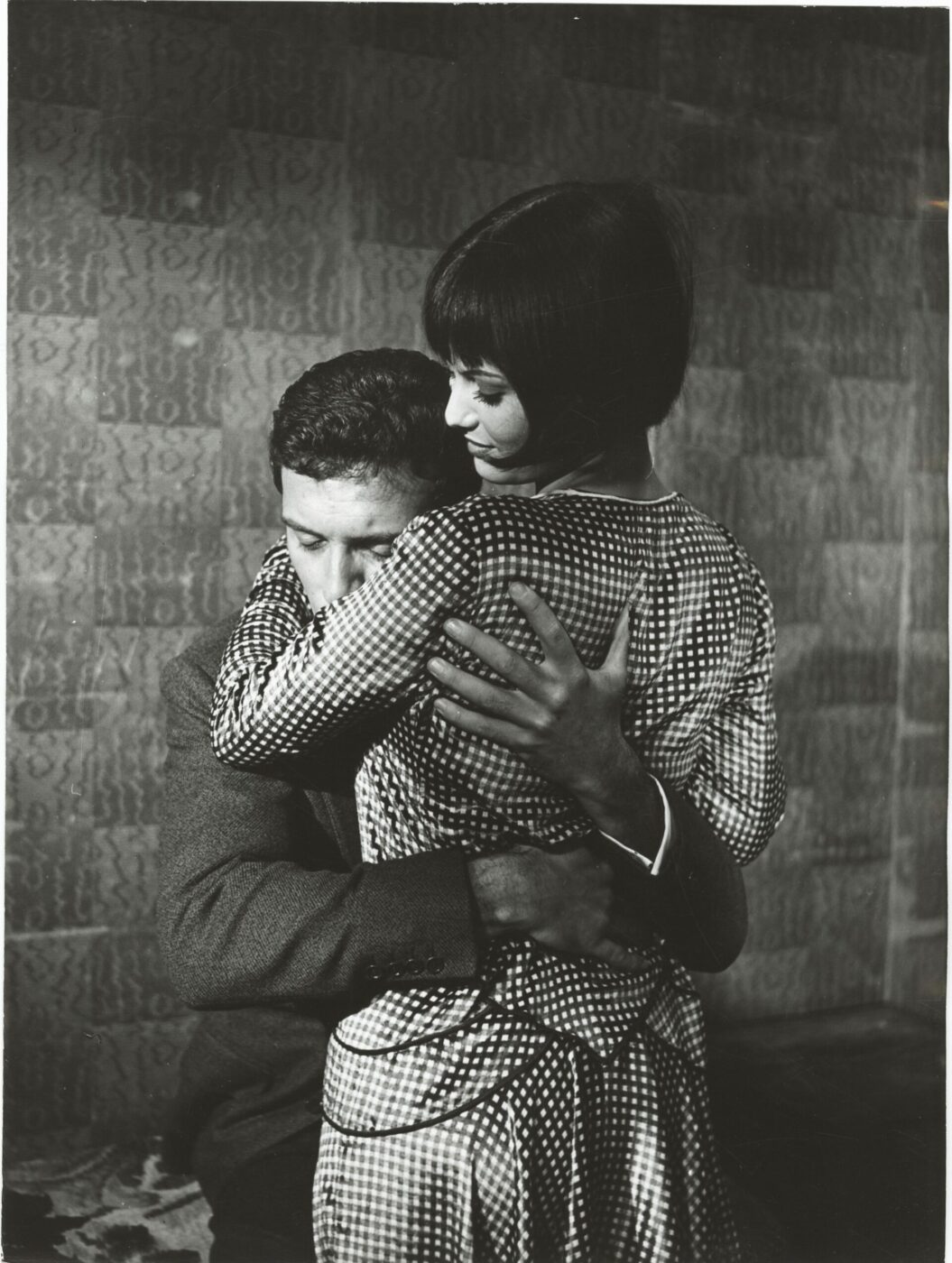

Enzo Staiola in a scene from the Italian film "Ladri di biciclette" (1948)

ENZO STAIOLA (1939-2025)

Neorealism’s Child Star

If you don’t recognize the name, you will remember the face: an eight-year-old boy delivering a performance of a lifetime in Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 neorealist masterpiece Bicycle Thieves. Like many performers of the era, Enzo Staiola was not a trained actor but an expressive child with an intensity that captivated De Sica, who discovered him on the streets of Rome. Central to the film’s emotional gravity, Staiola’s role as Bruno embodies neorealism’s focus on everyday suffering and human dignity. The performance transformed the child figure into a moral anchor of Italian cinema.

“In my view, Enzo Staiola incarnates one of the fundamental concerns of postwar Italian cinema: how individuals can bear witness to social injustice and moral collapse without taking an overt political stance,” says Francesco Pitassio, professor of film studies at the Department of Humanities and Cultural Heritage at the University of Udine.

Although Staiola continued to appear in films as both a child and later an adult, none matched the cultural impact of Bicycle Thieves, now widely regarded as a landmark of world cinema. “I believe that the greatest legacy of Staiola’s role in the Bicycle Thieves is the character’s merciful view of others,” Pitassio adds. “Bruno witnesses the moral collapse of his father, and in the final scene, it is the child who assumes responsibility, offering compassion rather than judgment.”

“I think that this sense of mercy, compassion, and awareness that unforeseen circumstances can lead individuals to seek solidarity is possibly the greatest legacy that the film, and Staiola’s character, left to Italian and world cinema. It’s no surprise that the film still exerts such widespread influence to date, far beyond the national boundaries,” Pitassio notes.

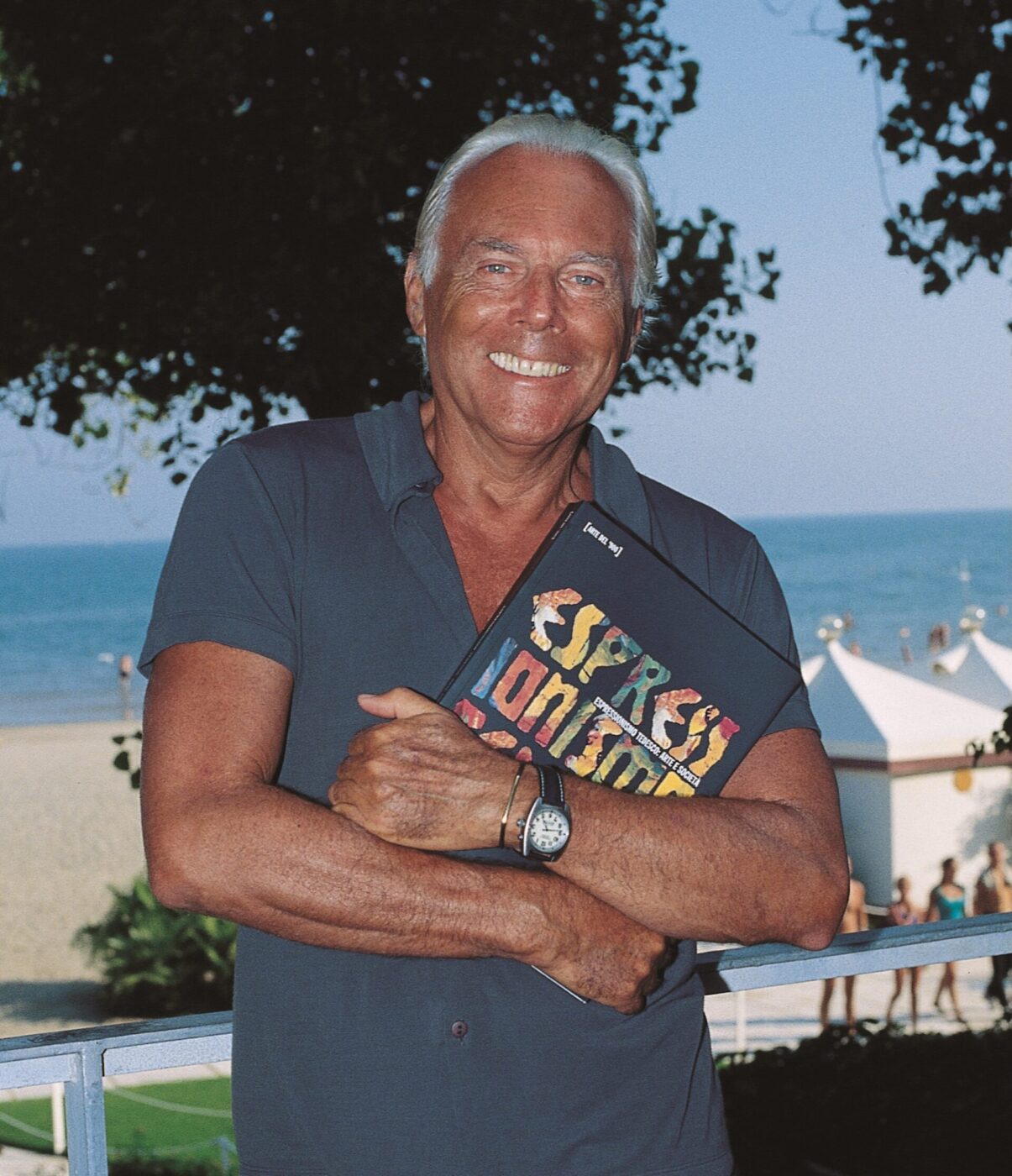

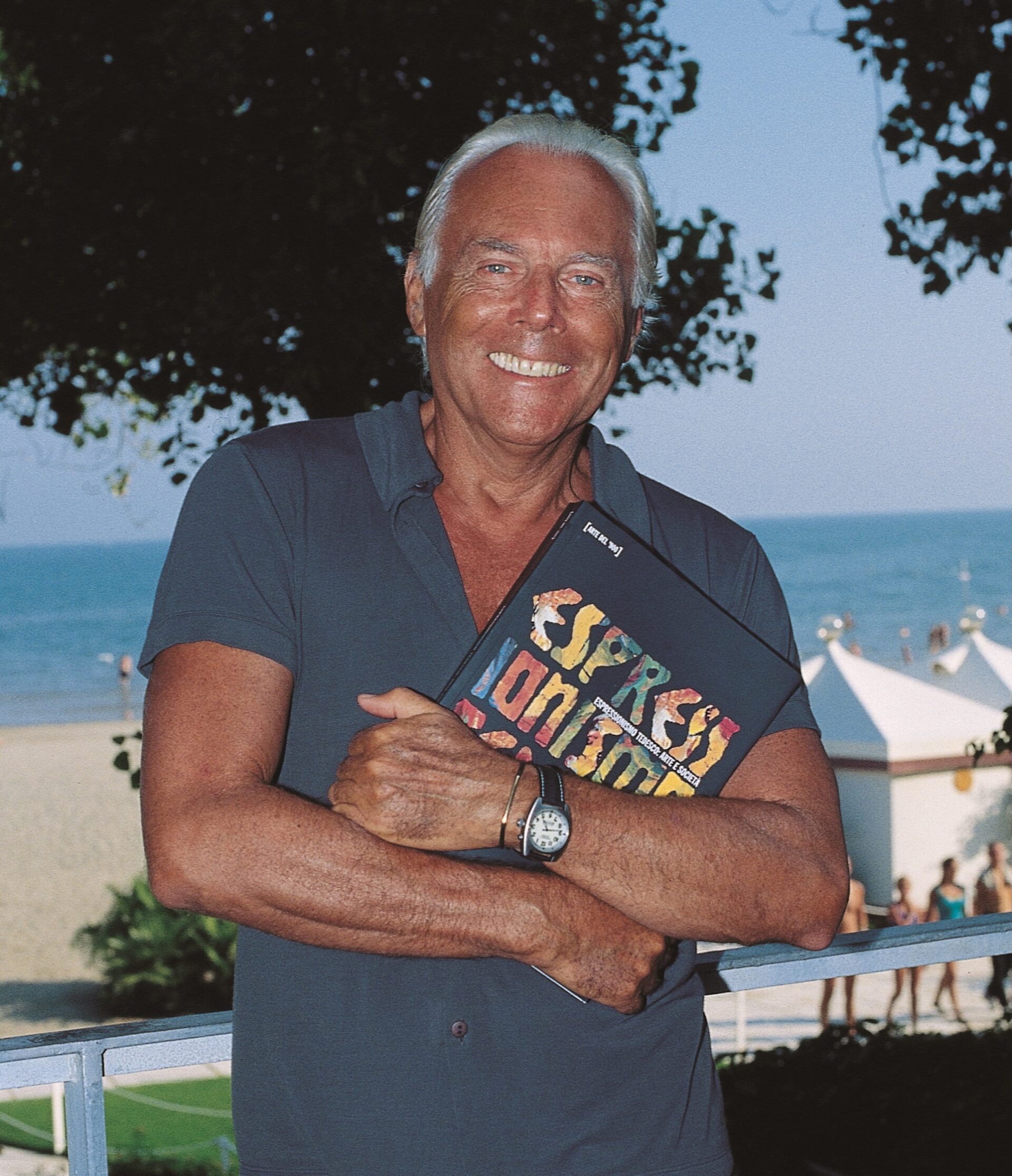

Giorgio Armani; Courtesy of GianAngelo Pistoia - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48266936

GIORGIO ARMANI (1934-2025)

“Il Re”

Getting dressed for work the morning after Giorgio Armani passed away felt strangely difficult. Surreal, almost. The streets of Milan were heavy with disbelief and somber reflection, a mood that quickly spread across the country. The barista, the school kid, the tourist, the church caretaker—everyone mourned because Italy had lost a piece of its soul, “Ciao, Re Giorgio”.

Italians love gestures, and Armani mastered the decisive kind. When he softened the tailored men’s blazer in the mid-1970s—flattening shoulders, loosening structure, letting fabric fall naturally—he rewrote the rules of power dressing without having to explain a word. He exported understated Milanese elegance to Hollywood and changed the face of womenswear in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, transforming couture from art and ornament into architecture. He controlled every aspect of his empire, from image to production, advertising, and global distribution. Armani transformed Italian fashion from artisanal spectacle into a disciplined, international system.

That discipline defined the man as much as the brand. Armani was a beacon of clarity, pragmatism, and restraint—qualities that resonated deeply in Italy’s collective imagination. We all wanted to be a bit more like Signore Armani. If your father owns a Giorgio Armani suit, your mother an Emporio Armani coat, your sister an Armani perfume, your brother an EA7 tracksuit, and your Nonna a midnight blue beaded Armani twinset from the late ’70s, your family is part of a national “wardrobe” that was as much about cultural pride as it was about the garments themselves.

In the tributes that followed his passing, it was Armani’s virtues and strength of character that stood out most: his loyalty to staff, his generosity of vision, his belief in consistency over spectacle. In a world obsessed with visibility and validation, he offered a more subtle lesson: “Elegance is not about being noticed, it’s about being remembered.”

Ornella Vanoni, 1970

ORNELLA VANONI (1934-2025)

“La Grande Signora della Canzone Italiana”

Can anyone listen to “L’Appuntamento” without misting up nowadays? The tender opening strings, the mellow piano, and then Vanoni’s voice—with its wispy tinge of melancholy. Released in 1970, the song became an unofficial anthem for first love, lost love, unrequited love, long-distance love, endless love… We’ve all been there, and Ornella Vanoni was there with us.

Imagine Milan in the shadows of the late 1950s: there is Vanoni, sharp-witted and barely in her twenties, singing about the city’s underworld (le canzoni della mala) for Giorgio Strehler’s Piccolo Teatro. Something was smoldering and defiant about her from the start. From there came the melodic melancholy of the 1960s and ’70s—“L’Appuntamento”, “La musica è finita”, “Senza fine”, “Domani è un altro giorno”—soundtracks to marriages, declarations of love, broken hearts, longing, or just simply “…the songs of my life”, as TV presenter Simona Ventura stated at the signer’s memorial service at Milan’s Piccolo Teatro in November.

Vanoni did not survive trends; she ignored them. Instead, she constantly reinvented herself for the pleasure of emotional and musical discovery, moving through jazz, bossa nova, and late-career collaborations with a sense of boundless authority. Self-ironic and disarmingly honest during concerts, interviews and public appearances, Vanoni never courted flattery or bowed to criticism, and few Italian female artists have aged so publicly, so musically, and so unapologetically.

At a time when women’s voices were expected to console or idealize reality, Vanoni sang about loneliness, boredom, erotic tension, and moral ambiguity. The women in her songs smoked, waited around, desired the wrong people, made mistakes, and acknowledged those mistakes out loud. In doing so, she changed the emotional vocabulary of Italian popular music, teaching us to linger in emotional complexity rather than rush toward some grand climax or conclusion. “She was an artist of gigantic anarchic elegance,” said singer and songwriter Francesco Gabbani.

The curtain might have fallen, the lights dimmed, the song over for 2025, but we all know that Signora Vanoni, “La Grande Signora della Canzone Italiana”, hasn’t really left us. Neither have the others, for that matter:

Domani è un altro giorno, si vedrà (Tomorrow is another day, we’ll see).