In the Dolomites, you’ll find cozy mountain cuisine influenced by three distinct cultures: Italy’s Mediterranean leanings, the Imperial ghost of the Austrian Habsburgs, and the ancient traditions of the indigenous Ladin people.

The Ladins, descendants of Rhaetian tribes and Roman soldiers, developed a survivalist cucina povera in the isolated, high-altitude valleys around the Sella Massif, relying on hardy rye and frying to add caloric density to meager harvests. This culinary bedrock was overlaid by centuries of Austrian rule—which ended only in 1919—leaving a legacy of butter over olive oil, smoked cures over fresh meat, and a penchant for mixing sweet and savory.

The best places to try Dolomitic cuisine are the rifugi, high-alpine huts that serve as pit stops for hikers and skiers; dining at them means warming foods designed to fuel life on the Pale Mountains. Here, 20 foods that define the Dolomites.

CANEDERLI (KNÖDEL)

These dense bread dumplings are the ultimate waste-not dish: cubes of stale white bread are soaked in milk and bound with eggs and chives (and often speck or cheese), boiled, and served floating in a clear, rich meat broth (resembling a cousin of matzo ball soup) or dressed with melted butter and sage. The famous primo has a pedigree that dates back to 1180, depicted in the medieval frescoes of Hocheppan Castle near Bolzano; legend has it canederli were invented by a clever innkeeper’s daughter who, threatened by hungry Landsknechte mercenaries, used leftover bread, eggs, and speck to form “cannonballs” that filled the soldiers’ bellies and saved the village.

SCHLUTZKRAPFEN

Known as mezzelune in Italian, these half-moon ravioli are a staple of the Ladin valleys, distinguished by a dough made of rye flour—historically the only grain hardy enough for high-altitude winters. This rye base gives the pasta a rustic, dark speckling and an earthy bite that stands in stark contrast to the silky egg pastas favored just south. Stuffed with spinach and curd cheese (quark) and strictly finished with nut-brown butter and chives, the result is a chewy, nutty, and classically Alpine primo.

SPECK ALTO ADIGE IGP

Speck is the child of two worlds, marrying the salt-curing traditions of the Mediterranean with the smoke-curing habits of Northern Europe. As farmers needed meat to last through the long, snowed-in winters, they spiced pork legs with juniper and rosemary, then cold-smoked them over beechwood for a deep-red cured meat that’s smokier than prosciutto but milder than German ham. While often eaten thinly sliced on a tagliere or stuffed into a panino, it also serves as a fundamental building block for local cuisine. You’ll find it diced into canederli, worked into all sorts of pastas and risottos, or wrapped around soft cheeses like Tomino before grilling.

Speck; Photo by Fotograf Frieder Blickle - Export Organisation Südtirol, der Handelskammer Bozen, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36474220

SPINATSPATZLN

While plain spätzle are common across the German-speaking world, this South Tyrolean variation blends puréed spinach directly into the batter to create vivid green “sparrows” (the dish’s name comes from Swabian dialect for “little sparrows”). The dough is pressed through a colander-like device into boiling water to create small, chewy dumplings that are tossed in a cheesy, creamy sauce with cooked ham—peak comfort food.

Spinatspatzln

APFELSTRUDEL (APPLE STRUDEL)

Tracing its roots back to Ottoman baklava, the apple strudel marched north with the Turks before settling in these apple-rich valleys. The technical marvel here is the dough, which must be stretched so thin you can read a newspaper through it; local folklore posits that making it like this was a test of a bride’s readiness for marriage. It’s rolled around a filling of tart local apples, pine nuts, raisins, and cinnamon, then baked until crisp and flaky, sliced, and served.

KAISERSCHMARRN

The “emperor’s mess” is a thick, fluffy pancake enriched with rum-soaked raisins, fried in butter, and torn into large caramelized chunks while still in the pan. Some say it was a pancake gone wrong that the chef frantically shredded to hide his mistake; others say it was made for the fitness-obsessed Empress Sisi, who rejected the dish, leaving Emperor Franz Joseph I to polish it off. Served hot and in the pan, it’s finished with powdered sugar and tart cranberry or plum jam. Be warned: it’s a pretty substantial dessert, meaning you’ll want to get one to share or go easy on the savory stuff.

KAMINWURZ

You’ll find various sausages all across the region—and they’re all great—but this one’s a must try. Kaminwurz (“chimney root”) is a raw, dark red sausage of beef and pork, named for the chimneys where they were originally hung to smoke and cure in the rafters. It offers a hard, satisfying chew and a concentrated smoky flavor profile; there’s also a paprika variation. Kaminwurz is typically eaten straight up as a snack or served on the aforementioned brettljause, accompanied by bread, cheese, and pickles.

Brettljause

This wooden charcuterie board is piled high with the region’s cured treasures: slices of speck, Kaminwurz sausage, mountain cheeses, and pickles. It’s always served with Schüttelbrot, a thin rye flatbread spiced with fennel and cumin and baked until hard and crunchy to survive long storage. Traditionally, the board was eaten every afternoon as the Marende (in Italian, merenda), tiding farmers over from lunch to dinner. Fun fact: farmers here used to eat five times a day to fuel their labor.

Brettljause

FRITTATENSUPPE

A prime example of the Alpine (and greater Italian) philosophy that nothing goes to waste, this dish repurposes leftover palatschinken—thin, egg-rich pancakes similar to French crêpes—by rolling and slicing them into ribbons known as frittaten. Served in a clear, piping hot beef broth, the herb-studded ribbons absorb the liquid like a sponge, becoming silky and savory.

Frittatensuppe

KASNÖCKEN

This dish is a heavy hitter from the Ahrntal valley, historically eaten by woodcutters directly from the iron skillet to keep it hot in the freezing mountain air. Unlike delicate gnocchi, these are dense dumplings made of flour, eggs, and water, pressed through a sieve and boiled. They’re then tossed in a pan with caramelized onions and copious amounts of pungent graukäse, melting into a gooey, stringy coating that sticks to the pan. You’ll have to fight your tablemates for the crispy crust, the best part.

Kasnocken; Photo by ©[email protected], CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50677020

MENÈSTRA DA ORZ & TUTRES

In the Ladin valleys, these two dishes are inseparable, forming the traditional Saturday lunch of the Dolomites. Menèstra da orz is a thick porridge of pearl barley and root vegetables, simmered slowly with a smoked pork shank until creamy. It’s strictly served with tutres (also known as tirtlan), large, disc-shaped fritters made of rye dough that are deep-fried until blistered and golden. Filled with sauerkraut and cumin or spinach and curd, they were a culinary trick for getting a small amount of filling to go a long way.

Menèstra da orz

GRAUKÄSE

Consider this the ultimate litmus test for the adventurous eater. After skimming every drop of cream to make butter for sale, farmers in the Aurina Valley used the leftover skim milk to make this extremely low-fat (under 2%) “gray cheese”. It has no rind and ripens from the outside in, developing a gray, crumbly mold and an aggressively pungent flavor profile. To temper the funk, locals traditionally serve it dressed with vinegar, olive oil, and raw onions—a preparation that, believe it or not, balances the intensity.

Graukäse

KAMINWURZ

You’ll find various sausages all across the region—and they’re all great—but this one’s a must try. Kaminwurz (“chimney root”) is a raw, dark red sausage of beef and pork, named for the chimneys where they were originally hung to smoke and cure in the rafters. It offers a hard, satisfying chew and a concentrated smoky flavor profile; there’s also a paprika variation. Kaminwurz is typically eaten straight up as a snack or served on the aforementioned brettljause, accompanied by bread, cheese, and pickles.

HIRTENMAKKARONI

“Shepherd’s macaroni” is a hearty masterpiece found in high-altitude mountain huts, originally made by combining ingredients a shepherd might have on hand or easily trade for. Pasta, usually penne, is tossed in a sauce that combines Bolognese ragù with cooked ham, peas, sautéed mushrooms, and cream. It’s often topped with mozzarella and baked until bubbly—a filling bomb designed for survival on the peaks.

Hirtenmakkaroni

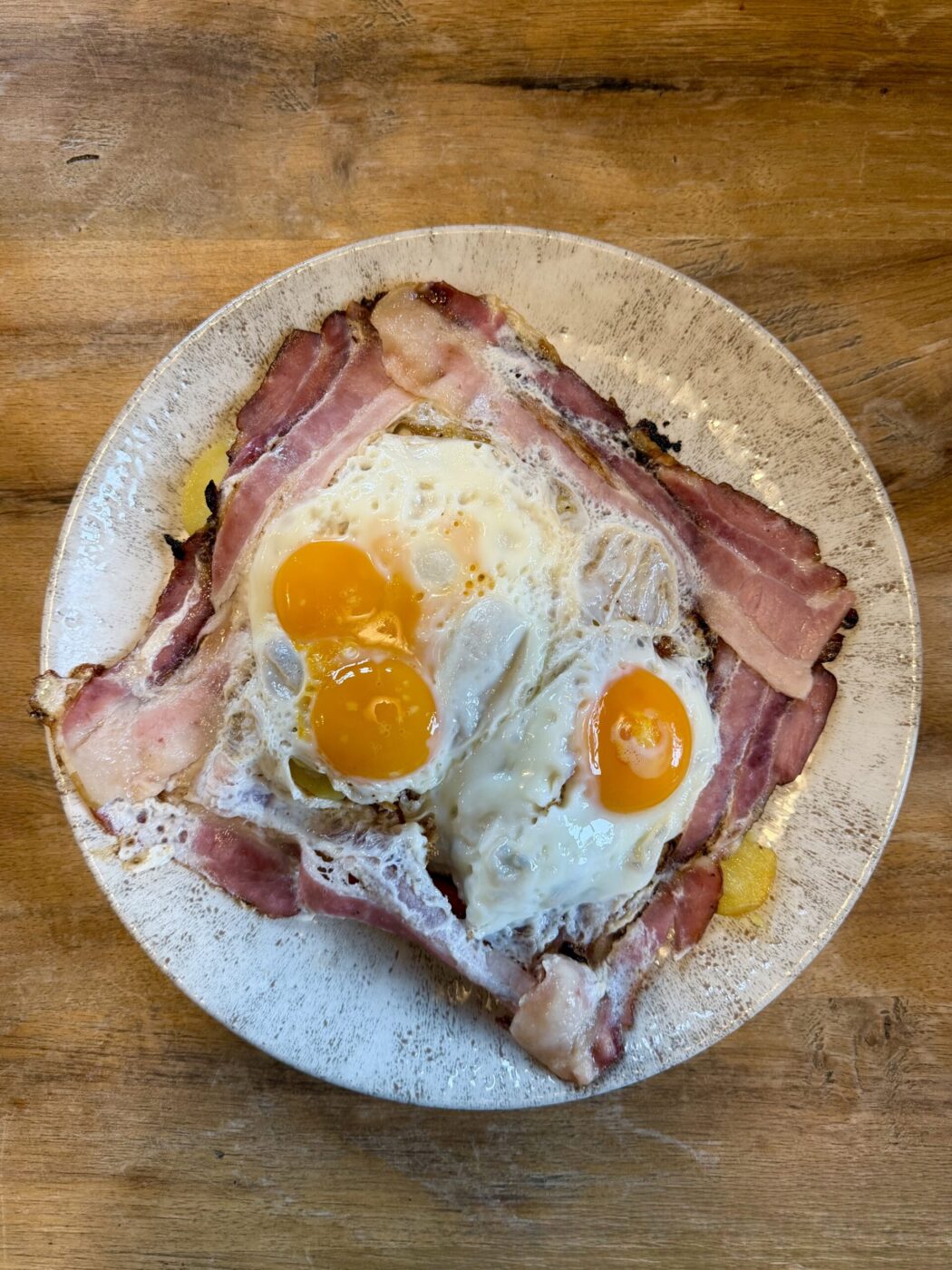

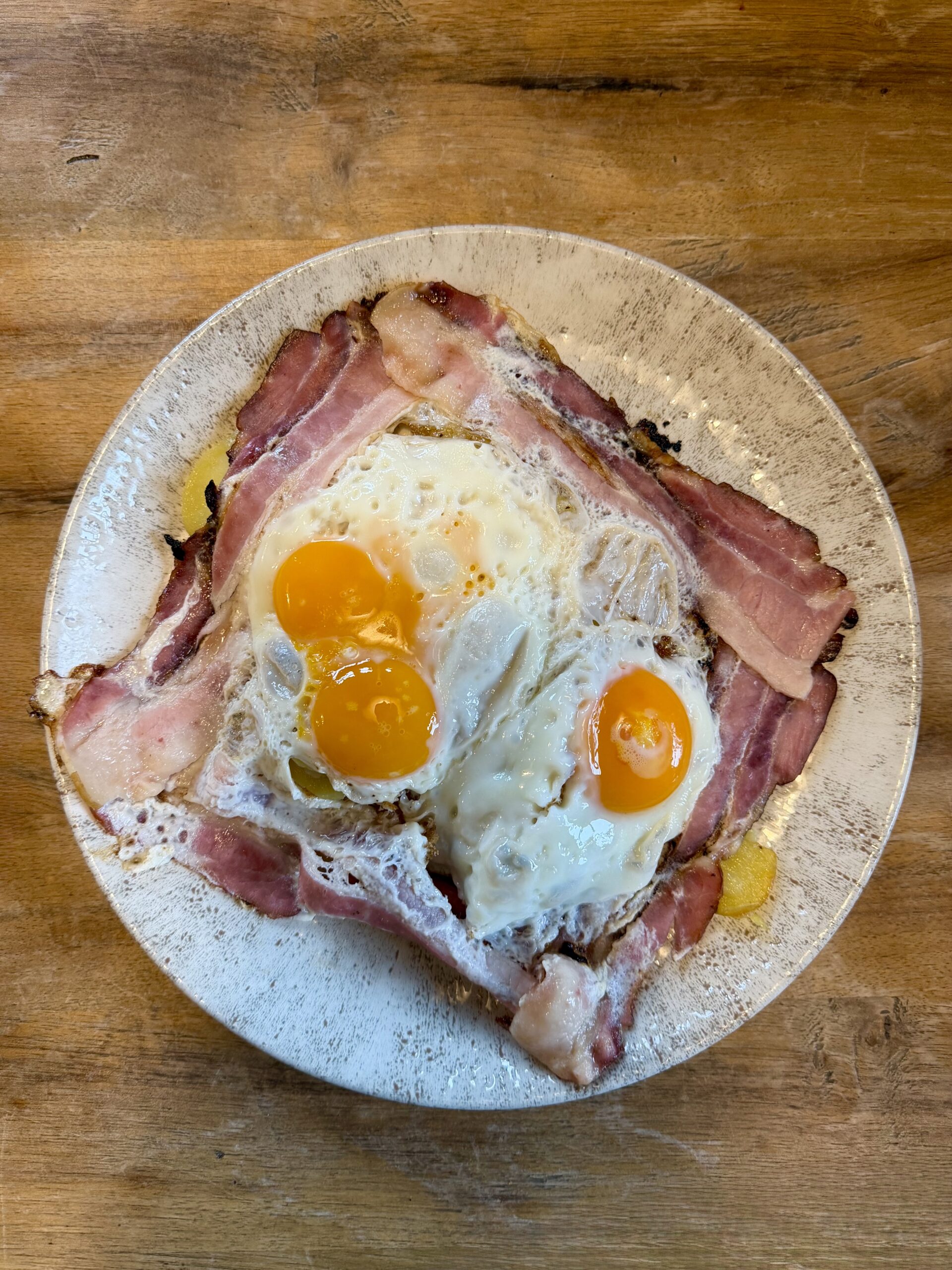

BAUERNGRÖSTL

This farmer’s fry-up is the traditional Monday lunch in South Tyrol, designed to repurpose the leftovers from the Sunday roast. Boiled potatoes are sliced and pan-fried in butter with onions, chopped beef or pork shoulder, and bacon until everything is crispy and golden, then topped with a fried egg. You want the potatoes to be well-browned, coated in the sauce created by the runny yolk.

Bauerngröstl

KRAUTSALAT

This cabbage salad—an omnipresent side dish—is blanched with hot salted water and dressed with oil, vinegar, and crispy speck bits. The secret weapon is the generous addition of caraway seeds, historically added as a digestive aid to counter the heavy, fatty pork dishes and cheeses that dominate the Tyrolean diet.

Krautsalat

GERMKNÖDEL

A fluffy dumpling with Austrian roots, made from soft yeast dough and hiding a core of powidl (spiced plum jam), germknödel is served swimming in a pool of vanilla custard or melted butter and finished with a signature topping of ground poppy seeds and powdered sugar. Originally a meatless fasting dish for Lent, it has since evolved into a ski-slope staple.

Germknödel; Photo by Takeaway - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42341724

STRANGOLAPRETI

“Priest stranglers” earned their name from the legend that clergy members during the Council of Trent indulged so gluttonously in these dumplings that they risked choking. Don’t confuse these with the strozzapreti found in central Italy, which is a long, twisted flour-and-water pasta shape. The Trentino version is green gnocchi made from stale bread, milk, and spinach. Boiled and served drowned in melted butter, sage, and a mountain of grated Trentingrana cheese, they should be pillowy (and easy to swallow), not rubbery.

Strauben

These spiral funnel cakes are the ultimate festival food, named after the German word for “rough” or “unruly” due to their messy shape. A liquid batter (often spiked with grappa) is poured through a funnel into hot oil in a continuous spiral, creating a crispy, plate-sized fritter served with cranberry jam. Traditionally prepared for weddings in the Pusteria Valley, the number of eggs used in the batter was historically a public display of the family’s wealth.

Strauben; Photo by Benreis - Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39776819

CAJINCÍ ARESTIS

These fluffy, half-moon-shaped “fried ravioli” are stuffed with spinach and ricotta for one of the Dolomites’ most pillowy comfort foods. The dough incorporates boiled potatoes—a crop that revolutionized mountain diets in the 18th century and prevented famine—which gives the wrapper a softer, gnocchi-like chew compared to the usual crispy fried dough.

POLENTA AND ANY SORT OF STEW

You’ll find polenta all throughout the mountains, specifically the reddish-colored Storo which is slow-cooked in copper cauldrons for a result that’s coarser than generic cornmeal. It’s the mandatory partner for heavy-hitting stews, whether from game meat like cervo (deer) or capriolo (roe deer), which are marinated in red wine and juniper until they melt apart, or goulash. The latter comes courtesy of the region’s Austro-Hungarian past, though here—unlike the dumpling or potato-loving traditions of Eastern Europe—this paprika-spiked beef stew prefers a sturdy polenta to soak up every drop of the sauce.

You may also find polenta taking center stage in the likes of polenta macafana (“hunger-killer” polenta) from the Val Chiese that swirls bitter wild chicory and plenty of butter and Spressa cheese directly into the cornmeal, or polenta carbonera, enriched with seasoned salamella sausage and grated cheese that was historically cooked by charcoal burners to survive the cold.

BONUS: BOMBARDINO

The name translates to “the little bomb,” and after one sip of this orange-yellow drink, you’ll understand why. Born in the 1970s—technically in nearby Livigno (Lombardy), but adopted religiously across the Dolomites as the official fuel of the ski slopes—it’s the Alpine answer to eggnog. The classic recipe is a 2-to-1 ratio of egg liqueur and brandy, served steaming hot and buried under a mountain of whipped cream. If you find it too cloying, or need to add fuel to the flame, order a Calimero, a variation that adds a shot of espresso. These are the perfect après-ski warmers, but we advise against drinking two before attempting a black diamond run.