The whole city of Venice is a stage set: palazzi flaunting their façades, gondoliers barking in striped shirts, churches packed to their domes with Tintorettos and tourists. But look closer—or better, lose yourself in the less-trodden sestieri—and you’ll find the best things are almost always behind an unmarked door, halfway down a calle that smells faintly of brine, or over on a satellite island.

So, if you’re sick of Saint Mark’s Square, the Rialto, and museums packed shoulder to shoulder, these are 10 places you’ve (probably) never heard of in Venice—two of which were spotted during a recent special event organized by Mytheresa and La DoubleJ!—from a labyrinth inspired by Borges to a cloister that’s the oldest urban vineyard in the city.

Palazzo Grimani

Palazzo Grimani doesn’t look like much from the outside—just another noble hulk behind Santa Maria Formosa in Castello. But inside, this Renaissance rebel is a clean-cut Roman fantasy. The Grimani family—specifically Giovanni, Patriarch of Aquileia and full-time antiquities hoarder—turned their ancestral home into a high-brow fantasia of classical architecture, art, and frescoes. His pièce de résistance was the Tribuna: a domed, Pantheon-inspired chamber designed to dazzle visiting cardinals and show off his stash of ancient Roman sculptures. Suspended in the center is a Roman replica of the Abduction of Ganymede, reinstated to its original position during recent restorations. The Tribuna’s coffered dome plays tricks on your eyes, the light shifts as you move, and the whole thing feels like an epic and slightly eerie temple to beauty and ego.

Palazzo Grimani is open to visitors with ticketed entry from Tuesday to Sunday, 10:00 AM to 7:00 PM. For more information, visit the official website.

Palazzo Grimani Museum

Labirinto Borges

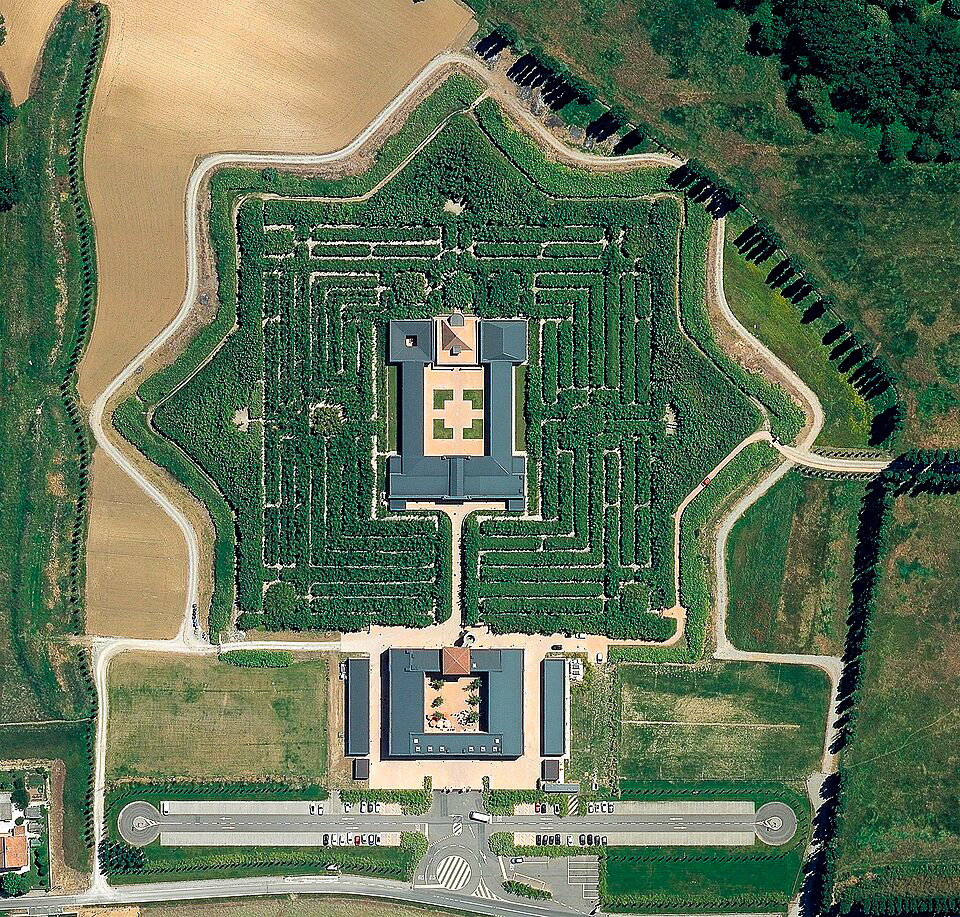

On the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, just across the water from Venice’s tourist thrum, a book-shaped labyrinth loops through the landscape. The Borges Labyrinth, opened to the public in 2021 and planted with 3,250 boxwood shrubs, was inspired by The Garden of Forking Paths—Jorge Luis Borges’ 1941 tale of espionage, ancestral riddles, and a novel that is also a maze. Designed by Randoll Coate, a British diplomat and labyrinth obsessive, the project began in the 1980s as a tribute to the Argentine author and was realized decades later through the vision of María Kodama, Borges’ widow, who dreamed of seeing it rooted near a great library.

Venice, that most labyrinthine of cities, obliged. She found the perfect match in the Giorgio Cini Foundation, whose Manica Lunga—a Benedictine dormitory-turned-book-lined marvel—gazes directly onto the garden. Now, visitors walk a full kilometer through the maze, encountering Borges’ favorite symbols tucked into the greenery: hourglasses, a tiger, a question mark, even his name reflected in hedge-script when viewed from above.

Open daily (except Wednesdays). Tours last around 45 minutes and include an audio guide with music by Antonio Fresa, performed by the Orchestra del Teatro La Fenice. Booking required at visitcini.com.

Labirinto Borges

Casa Masieri

Frank Lloyd Wright never laid a brick here, but his shadow still hangs over Casa Masieri—a building that became a battleground for 20th-century architectural ambition. On the Volta del Canal Grande beside Palazzo Balbi, it was meant to be a home for the young couple Angelo Masieri and Savina Rizzi. But when Masieri was killed in a car crash in 1952 on his way to Wright’s studio in Arizona, the plan shifted: the family asked Wright to design a guesthouse for IUAV architecture students instead. His daring proposal—angular, reflective, unapologetically modern—was too much for the city’s building commission, which also later turned down ideas from Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn.

In 1963, the project passed to Carlo Scarpa, who preserved only the façade and reinvented the interior. Completed after his death by Franca Semi and Carlo Maschietto, it became a hybrid monument: an old shell with a modern soul. A restoration in 2023 brought the building back to life, now hosting exhibitions, archives, and architectural research under the revived Angelo Masieri Foundation.

Visits are available by appointment from Tuesday to Saturday. To schedule a visit, please contact the gallery at +39 344 7269384 or via email at [email protected]. For more information, visit masieri.org.

Casa Masieri (on the left), next to Palazzo Balbi

Palazzo Diedo – Berggruen Arts&Culture

From noble residence to public courtroom to contemporary art crucible—Palazzo Diedo has had many lives. On the Rio di Santa Fosca in Cannaregio, this five-story Baroque block was built between 1710 and 1720 for the powerful Diedo family, its grand halls frescoed with allegories and wedding celebrations, its mezzanines adorned with stuccos and mythological reliefs. After the family’s bankruptcy, the city took over, turning it into a school and later a courthouse. Then, in 2022, collector-philanthropist Nicolas Berggruen acquired the palace and turned it into Berggruen Arts & Culture, a new center dedicated to contemporary art in the context of Venetian craft and history.

Palazzo Diedo reopened during the 2024 Biennale with the installation of 11 permanent site-specific works. One of the most captivating is Carsten Höller’s Scale of Doubt—a functional spiral staircase of Vicenza stone, marmorino Veneziano, and metal balustrades between the palace’s main floors. Inspired by Palladian forms and designed with a five-degree gradient, it turns a once-unfinished stairwell into walkable artwork. Palazzo Diedo reopened for the 2025 season on May 10th, with the exhibition “The Next Earth. Computation, Crisis, Cosmology.”

Open daily (except Tuesdays) with ticketed entry from 10 AM to 7 PM, last admission at 6 PM. Full program at palazzodiedo.it.

Palazzo Diedo

Palazzo Rocca

You won’t spot it unless you’re looking. Squeezed between Ca’ Rezzonico and the Accademia Bridge, Palazzo Rocca keeps a low profile for a house that’s seen emperors, poets, and pop royalty come through its doors. It started as Palazzo Contarini Corfù in the 14th century, got a souped-up Gothic addition in the 1600s, and stayed with the Contarinis until they ran out of heirs or money. In 1890, Count Riccardo Rocca bought the whole thing as a wedding present for his son Mario and his bride ND Moceniga.

The interiors are full Venetian splendor—arched courtyards, vaulted staircases, a private pier for a gondola entrance. Up top, the Specola, a turret with a view, has hosted everyone from D’Annunzio to Charles and Diana.

Unfortunately, Palazzo Rocca is open for private events only—but if you’ve got a wedding, a milestone birthday, or a fantasy dinner party in mind, you can’t get better than this.

Palazzo Rocca

Sant’Erasmo

Anyone with a passing familiarity with Venice will (hopefully) have heard of Sant’Erasmo. It’s the city’s backyard, the green smudge on the vaporetto map. But most don’t realize that, beneath the calm surface, it’s still a working patch of land, farmed to feed the city.

Fewer than 600 people live here, and yet the “Garden of Venice” grows a staggering share of the lagoon’s produce. Artichokes, radicchio, zucchini, cabbage, fennel—whatever’s in season. This is the stronghold of the castraure, the prized first-cut purple artichokes, now a Slow Food presidium. And in 2021, a group of 13 Venetian restaurateurs launched Osti in Orto, a grassroots farming collective on a plot once used for pigs and peaches. They turned fallow land into four hectares of thriving crops, harvested by hand and ferried straight into the kitchens of Venice’s best restaurants. Visitors can join guided tours of the farm and sample freshly harvested produce in the form of seasonal snacks.

Bring a bike or lace up your sneakers—a slow loop around the fields of the island is the quickest way to clear your head and get a hit of green. Time your visit right and you might land in the middle of the Festa del Carciofo Violetto (second Sunday in May), celebrating the island’s signature purple artichoke with tastings and cooking demos at Torre Massimiliana. In October, the Festa del Mosto brings out the torbolino—a cloudy, barely fermented wine—served with grilled fish.

Take vaporetto line 13 from Fondamente Nove (about 30–45 minutes). Get off at Sant’Erasmo Capannone or Chiesa.

Torre Massimiliana on Sant'Erasmo Island

Palazzo Contarini del Bovolo

Legend has it that Pietro Contarini built a spiral staircase in the late 1400s so he could ride his horse straight up to his bedroom. Whether or not that’s true, the Scala del Bovolo (“snail” in Venetian) remains one of the city’s most eccentric architectural flourishes—a corkscrew of arches and columns tacked onto the back of a modest palazzo near Campo Manin. Winding up 26 meters, it leads to a rooftop loggia with views over a sea of terracotta tiles and bell towers.

This place has also had an eclectic second life: a 19th-century inn run by a man known as “the Maltese” (rumored inspiration for Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese), a stargazing spot for German astronomer Ernst Wilhelm Tempel (who discovered a comet from the top in 1859), and a moody film location for Orson Welles’ Othello.

Open daily with ticketed entry from 10 AM to 6 PM (last entry 5:30 PM). Booking recommended here.

Photo by Petra Venezia - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

Complesso dell’Ospedaletto

Also known as Santa Maria dei Derelitti, this church in Castello once belonged to an orphanage. The facade alone would stop you in your tracks—four massive atlantes (muscular stone figures by Giusto Le Court) groan under the weight of the Baroque cornice. But the inside is even more spectacular: frescoes by Jacopo Guarana and Agostino Mengozzi Colonna stretch across the nave; paintings by Tiepolo, Palma il Giovane, and Pietro Liberi catch light from high windows; and overhead, a 1905 ceiling by Giuseppe Cherubini swirls between Rococo and Belle Époque styles.

The church dates back to the 16th century: famine hit the mainland in 1527, and the city responded by building wooden barracks for the sick and destitute. These grew into a stone complex with wards for men, women, and orphans—and eventually, this church, attributed to Andrea Palladio. Back then, however, music was the main draw. Like the other “Ospedali Grandi,” this one became famous for its all-girl orphan choir, trained by top-tier maestros and accompanied by an exquisite 1751 organ still in place today.

Open Thursday to Saturday, 3:30–6:30 PM. Church entry is free; guided tours of the full complex (including the Music Hall and Sardi’s elliptical staircase) available by reservation here.

Photo by Carlo Dell'Orto - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

Chiostro del Convento di San Francesco della Vigna

You come for Palladio’s facade and stay for the cloisters hidden behind it. One is all clean Renaissance geometry, arcades marching in perfect cadence, shadow slicing across stone; for centuries it was a burial ground for the Venetian elite. The other cloister makes you understand why the church’s name “della Vigna”—is no poetic flourish. The church stands on land once covered by vineyards, gifted in 1253 by Marco Ziani, son of Doge Pietro Ziani, to the Franciscan friars. Today, the vines are still going strong—tangled in cloister corners and sunning themselves against old stone. The friars grow refosco and teroldego, and bottle it all into a wine with the lofty name of Harmonia Mundi.

The complex is free and open daily from 8 AM to 12:30 PM and 3 PM to 6 PM. Please note that while the church and main cloisters are open to the public, access to the vineyard cloister may be restricted.

Photo by Didier Descouens - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

Tomb of Antonio Canova

Venice didn’t raise Antonio Canova, but it certainly knew how to bury him—in a stark white triangle of a tomb inside the cavernous Frari Basilica. The man was the superstar sculptor of the Napoleonic age, known for carving impossibly tender flesh from marble, resurrecting Greco-Roman ideals with surgical precision, and charming popes, emperors, and even Napoleon’s sister Pauline (whom he famously sculpted semi-nude as Venus Victrix).

The tomb, which Canova originally designed for Titian, was repurposed by his students after his death in 1822. Only his heart is interred here—the rest of his body lies in Possagno, his hometown, and his right hand is embalmed at the Accademia di Belle Arti. Allegorical figures (Sculpture, Painting, Architecture) mourn him on the steps; the door is slightly ajar, as if Canova just stepped out. Freemason symbols nod to his esoteric side, but it’s the restraint and elegance of the monument that lingers—proof that even in death, Canova edited his lines perfectly.

Open daily 9 AM–6 PM, with tickets from €2 to €5. More info at basilicadeifrari.it.

Photo by Didier Descouens

BONUS: Palazzo Papadopoli

Okay yes, this one is technically not a secret. But Palazzo Papadopoli—the building that Aman Venice calls home—is so spectacular it deserves a nod of its own. Just hope you’re lucky enough to be able to stay at the hotel—or get invited for a coffee or a cocktail. One of only eight monumental palazzi on the Grand Canal, it’s a rare Venetian hybrid: all 16th-century outside, Rococo flourishes and soaring Tiepolo ceilings inside, with a crisp layer of contemporary cool courtesy of designer Jean-Michel Gathy. And unlike most of its grand neighbors, this one comes with private gardens, two of them, between the canal and the palace.

Palazzo Papadopoli